Employee Relations May 2010

advertisement

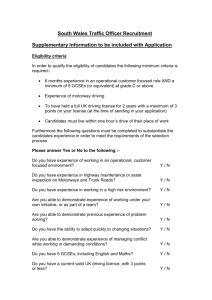

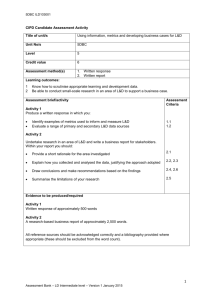

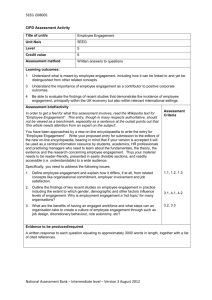

Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development Professional Development Scheme Generalist Personnel and Development Employee Relations May 2010 10 May 2010 13:50-17:00 hrs Time allowed - Three hours and ten minutes (including ten minutes’ reading time) Answer Section A and SEVEN out of ten questions in Section B. Please write clearly and legibly. Questions may be answered in any order. Equal marks are allocated to each section of the paper. Within Section B equal marks are allocated to each question. If a question includes reference to ‘your organisation’, this may be interpreted as covering any organisation with which you are familiar. The case study is not based on an actual company. Any similarities to known organisations are accidental. You will fail the examination if: • • you fail to answer seven questions in Section B and/or you achieve less than 40 per cent in any section. Registered charity no: 1079797 1 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 SECTION A – Case Study Note: It is permissible to make assumptions by adding to the case study details given below provided the essence of the case study is neither changed nor undermined in any way by what is added. The East Highlands Regional Authority (EHRA) is a large public service provider. Over the next six months EHRA is required to implement a number of changes that are part of the final stages of local government reorganisation. EHRA currently employs 1600 people, having already reduced its workforce by 350 during the first two stages of its reorganisation plan. As is common in many other regional authorities, there is strong union membership and employees are currently represented by three trade unions: UNITE (THE UNION), UNISON, and the GMB. The national government’s guidelines for reorganisation stipulate that local and regional authorities must “consider practical arrangements for implementing structural change, having regard to the need to minimise any risk of disruption to the authority’s service and secure value for money for the local and national taxpayer”. Furthermore, jointly agreed consultation arrangements have been established at a national level between the government, unions and the local authority employers association that outline protocol arrangements in the case of reorganisation and potential redundancy. In outline these include: • all authorities should discuss and agree local arrangements for people management issues with recognised unions; • agreement should outline the issues to be covered; • If agreement cannot be reached, disagreements could be escalated to a chief executives’ panel; and • Arrangements must pay attention to statute, local convention and good practice. EHRA has drawn up a plan that will involve some redundancies. In a recent workforce strategy review, the areas of ‘adult community care’ and ‘regional education support services’ were felt to be the most vulnerable. An audit of demographic trends across the authority’s region showed that demand for adult community care will decrease over the next decade. This would result in the loss of about 35 care workers over three to five years, on a phased basis as demographic trends change according to predictions. The management team is conscious that adult care can be a highly political issue given the sensitivity and community value attached to assisting elderly people in their homes. All affected staff are members of Unite. With regard to the regional education support services, functions such as IT and school liaison offers are services that can now be carried out by the Regional Education Authority (REA). It is therefore proposed to transfer all 30 staff to the REA office, which is based some Registered charity no: 1079797 2 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 30 miles away from the current work location. The REA is a different employer and the office has only recently opened and requires about 20 staff to achieve a full complement. This affects clerical employees who are represented by UNISON. Other relevant information includes: • UNISON has a policy of balloting all members for industrial action in the advent of compulsory redundancies. • Local government authority protocols and guidelines stress the importance of consultation and seeking agreement with staff and unions, where possible. These guidelines offer best practice over-and-above minimum statutory collective redundancy rights. • About 20 of the ‘at risk’ 35 care workers are temporary and casual employees. • The clerical employees who have worked in the education service are all longserving full-time permanent employees. About five of them are close to retirement and the local government pension scheme can offer enhanced pension contributions for early retirement. • The previous reorganisation phases were all successfully negotiated through natural staff wastage, early retirement and TUPE transfers of outsourced functions. Therefore EHRA has never had to make anyone redundant, on either a voluntary or compulsory basis. You have been asked by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) to lead a small team to investigate possible options to help achieve the final reorganisation phase that will result in a workforce reduction of 55 staff: 1. Outline and evaluate to the CEO a number of possible options that may be proposed to the trade unions. 2. Justify a programme of consultation with the relevant trade unions and staff who may be affected. 3. Drawing on research, identify any possible barriers and implementation issues in seeking to achieve the options proposed. It is recommended that you spend about one-third of your time on each of the tasks PLEASE TURN OVER Registered charity no: 1079797 3 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 SECTION B Answer SEVEN of the ten questions in this section. To communicate your answers more clearly you may use whatever methods you wish, for example diagrams, flowcharts, bullet points, so long as you provide an explanation of each. 1. Using research evidence, define the concept ‘employee engagement’ and explain the significance to your organisation. 2. Email from a line manager in your organisation: “Could you please explain to me the roles and functions of the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC)? Does this body have any authority over our company, and if so, what?” Draft an email reply. 3. Your Chief Executive Officer (CEO) wants to reduce absenteeism. Using good organisational practice and/or research evidence, what would you advise to help achieve this goal? 4. Is the UK government a major or minor party in employee relations? Use research evidence to explain and justify your answer. 5. Identify and evaluate the main external factors that are likely to impact on the employee relations climate at your own organisation in the next three years. 6. An employee in your company has come to you for advice. She is worried that because she is called on to work overtime most days and weekends, she may now work in excess of the working time regulations. What advice would you give her and why? 7. Your Human Resources Director is concerned about an increase in the number of employee grievances. She has also noticed that more grievances seem to be progressing to higher levels. She would like you to arrange a briefing session for line managers about the skills necessary to handle a grievance in the hope of reducing these trends. Justify what you will say in the briefing session. 8. Your CEO has been notified by the full-time union official that because agreement could not be reached on a pay settlement, the union intends to ballot its members for industrial action. Explain to him the differences between ‘official’ and ‘unconstitutional’ industrial action using examples where possible. Registered charity no: 1079797 4 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 9. Using research evidence and/or examples of organisational practice, explain why few employers communicate with or involve their employees effectively. 10. Email from a friend seeking your professional advice: “I have had a request for adoptive leave from a gay member of staff. Is he entitled to such leave, and if so what is it?” Justify what you will say in response to your friend. END OF EXAMINATION Registered charity no: 1079797 5 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 Introduction This report reviews the May 2010 Employee Relations exam diet for the Professional Development Scheme (PDS). A total of 469 candidates sat the exam from 43 centres. A total of 345 candidates passed the examination (a 73.5% pass rate). I would like to thank and acknowledge the help and support of the marking team who provided dedicated assistance in marking the exam scripts in a professional and timely manner: Hamish Mathieson, Anne Jones, Carol Atkinson and Deborah Hann. The help of the CIPD membership and Education Department has been particularly valuable: Peter Herman; Annie Matthews; and Carleen Stonell. The examination consisted of a two-part exam paper. Section A of the paper was a case study which invited candidate to review a number of options and advance proposals concerned with a collective redundancy situation. The case study covered knowledge indicators concerned with: i) the changing economic and social context for employee relations in a public sector setting; ii) the parties affected by redundancy; iii), the processes for informing and consulting about redundancy; iv), the possible outcomes; and v), the skills related to managing redundancy effectively. Almost all candidates who tackled Section A attempted the three tasks. As in previous years the second part of the paper, Section B, contained ten questions from which candidates were required to answer any seven. Section B covered the scope of the PDS standards for Employee Relations. These included: the processes for effective employee relations (employee engagement, working time, employee involvement, types of industrial action, adoptive leave); the environmental context affecting for employee relations (external environmental factors, statutory rights); employee relations skills and advocacy (absenteeism, grievance handling, working time); and the role of the parties in employee relations (government/CAC, trade unions, management). The questions were designed to test candidates’ knowledge of the standards by drawing on organisational practice, problem-solving skills, advocacy and advice, and contemporary research evidence. In assessing the performance of candidates, the markers took into account: • the candidate’s knowledge and understanding of the subject matter or issues raised by the question; • the ability of the candidate to define, describe, apply and analyse employee relations techniques; • the application of the candidate’s employee relations skills (for example, application of concepts, accuracy and clarity of communication etc) to address issues/ problems/procedures raised in the question; • the extent to which the candidate’s answer reflected clarity of business application; Registered charity no: 1079797 6 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 • the knowledge and understanding of employment relations contexts and the wider environment in addressing organisational policy/practice/procedure; • the knowledge and understanding of contemporary research evidence published in journals (the Trade Press and academic), CIPD, Government and Government Agency publications. Summary Breakdown of Grades and Results The distribution of grades and results was as follows: May 2010 Grade Number Distinction Merit Pass Marginal fail Fail Total 11 68 266 12 112 469 Percentage (to I decimal point) 2.3 14.5 56.7 2.5 24.0 100 The figures shown are simply calculations based on the number of candidates sitting the examination in May 2010, whether for the first or a subsequent time, and are for interest only. They are not to be confused with the statistics produced by CIPD headquarters, which are based on the performance of candidates sitting the examination for the first time. It is from these figures that the national average pass rates are calculated. The total number of candidates who passed the exam was 345 (73.5%, including pass, merit and distinction awards). Some of the general trends can be broken down further, as follows: • 67.5% of all candidates passed Section A (including pass, merit and distinction). • Performance was much lower in Section B, with 50% of candidates passing. • One-third (31%) of all candidates sitting the examination obtained an overall pass but had marginally failed one section, with their mark in the corresponding section of the paper compensating for an aggregate pass. This trend is important to note as it indicates many candidate only barely scrape a pass. • 47% (223 candidates) who passed the exam received a mark of between 50-55% inclusive. • At the same time, the spread of marks is much improved for this exam diet, with a higher proportion of merit and distinction awards than in previous years. • 11 candidates received an overall distinction grade, with 68 candidates obtaining a merit. • 12 candidates (2.5%) ‘marginally’ failed the exam. • 20 candidates received a mark of less than 40%; Registered charity no: 1079797 7 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 • 7 candidates answered less then seven questions in Section B. The breakdown of performance by section and each question was as follows: Question N o. of Answers No. Passing % Pass Rate Section A 469 317 67.5 Section B Overall 469 233 50 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B7 B8 B9 B10 386 274 450 316 384 282 458 152 340 211 254 139 335 206 301 183 299 93 125 100 66 51 74 65 78 65 65 61 37 47 The most popular questions answered in Section B were Question 7 (grievance levels and skills), Question 3 (absenteeism), Question 1 (employee engagement), and Question 5 (external environmental factors affecting employee relations). The least popular questions were: Question 8 (official and unconstitutional industrial action), Question 10 (adoptive leave), Question 6 (working time regulations) and Question 2 (functions of the Central Arbitration Committee). Performance was strongest in the some but not all of the more popular questions (Questions 1, 3 and 5). General Considerations/Feedback on overall candidate performance Before reporting in detail on the performance in Sections A and B, several general observations can be made with respect to some major areas, which can be used by candidates sitting examinations in the future. • Weaker answers often failed to answer the question that was asked. For example in Question 9, poor performing did not explain the reasons why an employer may not communicate or involve employees effectively. Instead they tended to list several employee involvement mechanisms and assumed they were effective in their organisation. Similarly for Question 2 on the functions of the CAC, many candidates referred to ACAS explicitly or described the roles of ACAS, not the CAC. • Far too many of the weaker candidates peppered their answers with unconvincing assumptions or grand over-generalisations which result in unconvincing arguments. This applies to both Section A and B answers. Registered charity no: 1079797 8 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 • Candidates did not always explain and justify their answer or apply their knowledge to organisational practice when specifically asked to do so by the question. For Question 5, for example, weaker answers tended to describe very micro issues within their organisation (for example, short-time working or layoffs) without contextualising these in relation to knowledge about broader environmental factor changes affecting their organisation (for example, political change or the economy etc). • Answers displayed minor and/or major factual errors. This was especially evident for Question 2 (CAC), Question 6 (working time regulations), Question 9 (employee involvement) and Question 10 (adoptive leave). • Answers were not always given in the manner requested; for example, advice to an employee, line manager, CEO, or briefing session etc. Even candidates with reasonably solid answers did not always do this, which meant markers were limited in awarding grades at the higher end of the scale. • Seven candidates did not make a serious attempt at tackling the required seven questions in Section B. It is important to at least attempt seven questions as any less means an automatic fail with no discretion. Section A Section A was obligatory with a reasonably strong pass rate of 67.5%. Of those candidates who passed Section A, 28% achieved a merit award for the section; with 4% achieving a distinction for the case study. The bulk of candidates passing Section A did so in the 50-55% band. The case study was set in a public sector context; that of the East Highlands Regional Authority (EHRA), with a number of substantial changes involving organisational restructuring and redundancy. The case linked to several employee relations issues that candidates ought to have been reasonably familiar with given related changes in the economy more generally. These matters also related to several aspects of the employee relations PDS knowledge indicators and standards (see above). EHRA was described as a large public sector service provider, facing downsizing owing to government restructuring plans, and comprised a multi-union recognised workforce. Candidates were required to tackle three related tasks: consider a number of options to present to the recognised trade unions; detail a programme of consultation; and consider possible barriers and implementation issues related to the proposed options. Task 1 The first task asked candidates to outline a number of possible options concerning redundancy and change to the Chief Executive Officer which could be proposed to the recognised trade unions. Some candidates produced very strong answers in terms of justifying a number of central and relevant options that could be considered. Weaker or Registered charity no: 1079797 9 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 failed answers either simply regurgitated the case material, or outlined the need for redundancy without considering other possibilities. Importantly, the case context gave signposts for a possible reduction in 45 of the targeted 55 posts. Most candidates picked up on this and directed attention to some of the more obvious options: possible TUPE transfer for staff in the RAE division; early retirement for about 10 employees who may not be able to be accommodated through a TUPE transfer (for example, close to retirement); voluntary severance; consider not renewing or extending temporary contract employees. Stronger answers picked up on the 3 year lead time, arguing that precise numbers may change over time and therefore making 55 redundant straight away was not necessary. Of some concern was that weaker candidates often assumed they could simply dispense with temporary contract employees almost immediately, without considering the organisation’s obligations towards these staff, recognising that such employees have rights even though they are temporary. Poor performers did not really explain or seek to justify why their options might be convincing to the trade unions, as asked for in the task. Too many candidates assume that the options will be accepted without any union backlash, which lent for some rather unconvincing answers. Task 2 The second task was connected to the first in that it required candidate to detail a programme of consultation with the trade unions. Answers needed to demonstrate knowledge and understanding that this was a collective redundancy situation, involved multiple trade unions recognised at EHRA, and there are specific requirements as to what is meant by ‘meaningful consultation’. Again many candidates were reasonably accurate with basic consultation requirements (for example, in excess of 30 employees; 30 days notice etc). Some of the stronger answers provided some innovative and convincing ideas about improving consultation and communication over-and-above statutory requirements. However, very few candidates were able to cite or include recent case law about the importance of meaningful consultation and such consultation cannot be less than ICE 2004 regulations (for example, UK Coal Mining v NUM, 2006). Those who did make this observation, even without the legal citation, often achieved a merit award. Some of the higher end answers did more than describe basic information or list options, and produced higher quality analytical judgements about the importance of meaningful consultation, such as specifying key issues relating to management proposals, inviting unions to help search for cost-effective alternatives to avoid or mitigate the extent of redundancy, and explaining managerial obligations with regard to how they consider and respond to unions ideas. Often the key discriminator at the top end of the marks band was analytical syntheses of the ideas presented. Task 3 The final task asked candidates to consider two important matters: possible barriers to the options proposed; and implementation issues. While there were some very strong answers overall, this was by far the weakest part to many answers. Weaker candidates simply failed to consider the very real barrier of union opposition, or simply noted possible union resistance as a footnote, without elaborating its implications or considering how to manage union opposition. It was disappointing that very few candidates extracted material from the Registered charity no: 1079797 10 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 case study about the use of a chief executives’ panel to mediate barriers or union concerns. Better candidates did elaborate on union opposition in terms of what it might mean for specific service provision or grades of staff. Some of those at the top end went further and considered the broader political dynamics of care provision by a local authority. Weaker and failed answers did not identify any specific implementation issue. Stronger candidates identified and justified specific actions, including who might be responsible. Because of the long (3 year) lead time, some imaginative answers build in mid-term review options given the uncertainty the same numbers would be required at such a point in the future. Section B Question 1 Over the past few years the use of the term ‘employee engagement’ has been almost ubiquitous in virtually every answer to every question. One may assume this is both important and familiar to candidates. This proved to be the third most popular question in Section B, and 66% of candidates passed. The question related to the ‘process’ elements of the employee relations standards. Weaker answers simply did not provide a clear definition and explanation of ‘employee engagement’ as a discrete concept. Those who failed often referred to engaging employees as being part of an employee involvement programme, or as a part of the Purcell AMO model of high performance. Surprisingly, many pass answers did not even refer to the government’s MacLoad report on the matter (MacLoad and Clarke, 2009), or to the recent ACAS discussion document about employee engagement. The CIPD define engaged employees as those ‘who do their best’, ‘go the extra mile’, identify with the organisation and its values’. Research by Truss (sponsored by the CIPD) points to a three dimensional concept, including: Emotional Engagement (involves organisation members being emotionally attached and involved with their work), Cognitive Engagement (employees are clear about their work mission and what it achieves for the organisation); and Physical Engagement (willingness to go the extra mile for the organisation). Pass answers rarely gave such explicit definitions but did tend to describe the emotional and working harder dimensions with sufficient clarity. Only a few high performing answers cited quality research such as that by Truss, and explicitly related the significance of the concept to specific organisational outcomes (for example, commitment, job satisfaction, motivation, discretionary effort). Question 2 Around 50% of candidates who tacked Question 2 passed, with some variable levels of performance between pass and merit answers. The question related to the ‘context’ part of the standards. It asked about the roles and functions of the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC) and, importantly, whether the CAC has any particular authority over organisational management. Failed answers tended to get confused and referred to other bodies other than the CAC, such as the Certification Officer and ACAS, which are different to the CAC. Other answers that either failed or marginally passed/failed often started on the right tracks, although went off on a tangent. For example, quite a few candidates gave too much detail on things like statutory trade recognition procedure. While the latter is a functional area of the CAC, some answers diverted too much into the legality of trade union recognition, for Registered charity no: 1079797 11 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 example, and not how the CAC regulates the process. Pass answers accurately defined the CAC as a state agency not subject to directions from a government minister. Its legal authority includes making decisions in a number of specific areas: where an employer fails to disclose information to a recognised trade union for the purpose of collective bargaining; to adjudicate in disputes concerning the establishment of a European Works Council; to establish the procedure or instigate a ballot on receipt of a request for trade union recognition; and to establish arrangements in relation to the Information and Consultation of Employees (ICE) Regulations, 2004. Question 3 This was the second most popular question with a high pass rate of 74%. The question related to the ‘skills’ part of the employee relations standards concerned with managing absenteeism. Overall, this seemed to be a relatively straightforward question for most candidates who could define absence. Many referred to relevant survey data on the general cost and extent of absenteeism, noting that unplanned or unforeseen absences cause most problems. Higher marks were awarded for the quality of the various options that could help achieve a reduction in absence to the context of the scenario given in the question: return to work interviews; accurate record keeping, benchmarking with comparable organisations/sectors; disciplinary sanctions/actions. Question 4 Question 4 was drawn from the standards about the role of ‘parties’; specifically the role of government as a major or minor influence on the conduct of employee relations. Some 65% of candidates passed. Predictably, almost all candidates viewed the government as a ‘major’ party capable of influencing employee relations, although this was not necessary for a pass as it could have been argued that under voluntarist employee relations, the government has less of a direct and more of an indirect role. Failed answers did not demonstrate sufficient knowledge or understanding about the ways government may affect employee relations, such as a legislator, peacemaker, economic manager etc. Pass and merit answers did define and explain these in sufficient detail. Question 5 Question 5 had the highest pass rate of all Section B questions, at 74%, taken from the ‘context’ part of the PDS standards. Poor performing answers did not define and explain accurately the range of environmental context factors that can influence employee relations at the organisational level. Several weak answers diverted their attention to very micro organisational issues without connecting these to broader context factors. For example, some candidates mentioned in minute detail the management of temporary or contract staff, but did not relate this to changing labour market or economic conditions. Better performing answers utilised two or more particular context factors and explained how they affected employee relations at their organisation. Typical factor changes included: economic issues (recession, global market pressures); political (role of/change in government); legal (EU directives or specific laws); technology (affecting employee skill levels, the number of employees required). Other factors could have included social change or ideological values, Registered charity no: 1079797 12 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 but these were not high on the agenda for candidates (for example, ethics, changes to corporate governance, values about collectivism or individualism etc). Question 6 This was one of the least popular questions, although had a respectable pass rate of 65%. The question was taken from the employee relations ‘processes’ part of the standards and asked for advice about working time regulations. Weak answers offered very poor professional advice or contained inaccuracies about the working time regulations (for example, did not accurately state the regulations such as 48 hour maximum week over a defined time period, or that there are opt-in or opt-out options). Some candidates answered by referring to the process of raising a grievance, which if combined with solid knowledge about work-time arrangements achieved higher marks. Question 7 This was the most popular question in Section B and 65% of candidates passed. The question was concerned about grievance handling skills, taken from the ‘skills’ part of the standards. Several candidates failed to mention relevant skills, and instead described a grievance procedure and the stages of a grievance. Some very high marks were obtained for this question for those who identified and explained relevant skills, and commented how these may help reduce higher level grievance progressions. Typical skills included: listening - good listening skills allow managers to acquire information that can inform better decisionmaking; interviewing - helps a manager probe and clarify matters and enables employees to articulate their grievance more fully; communication skills - these include written and oral to articulate and explain matters; mediation/Influencing - to be able to explain and persuade others about an outcome and why a decision has been reached. Question 8 This question was the least popular question, although those tackling it did reasonably well, with an overall pass rate of 61%. The question related to both the ‘context’ of industrial action and the ‘parties’ to employee relations, specifically trade unions considering taking industrial action. The question asked candidates to distinguish between ‘official’ and ‘unconstitutional’ industrial action. Failed answers did not accurately or clearly distinguish between these two concepts. Pass answers tended to be reasonably strong. ‘Official action’ has been sanction by a trade union and the correct legal procedures for balloting followed. ‘Unconstitutional action’ may either be illegal in nature (for example, secondary action), has not be formally sanctioned by the union, or no ballot has been held or the ballot has been questioned. Some candidates were able to relate to recent examples (Royal Mail, Lindsay Oil Refinery). Candidates could have achieved higher marks had they commented that the legal distinctions do not always prevent ‘unconstitutional’ action and in reality such matters can be quite complex. Question 9 This had the lowest pass rate of all Section B answers, at 37%. The question, taken from the standards concerned with employee relations ‘processes’, required candidates to explain Registered charity no: 1079797 13 Employee Relations EXAMINER’S REPORT May 2010 why few employers communicate or involve employees effectively, drawing on research evidence. Far too many candidates failed to define employee involvement accurately or convincingly. Many others reiterated that employee involvement is a good thing and leads to higher performing organisations, without answering what the question asked, which was why employee involvement does not always achieve such things. There was little knowledge of the research evidence on the matter from the likes of Marchington, Wilkinson, Ramsay, Gollan, Dietz, Danford (among others). Only a few candidates knew about the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BiS) research, reported in People Management. This research shows that only 24% of employees said that their employer had clearly articulated business objectives to the workforce, and a third did not know (or doubted) there was a business plan. Other reasons for the lack of effective involvement include: limited people management skills by line managers; poorly integrated involvement mechanisms; employer interest in consultation tends to wax and wane over time; political barriers as consultation is a power-centred issue; employee interest also wanes. Some candidates articulated management style as a reason, which is only partly relevant and unconvincing as a primary or exclusive reason. Question 10 Question 10 was the second least popular question, from the ‘processes’ section of the standards. The question asked candidates to provide professional advice about adoptive leave rights, and 47% passed. Strong answers explained very well two things: that there are eligibility factors for adoptive leave; and secondly, what the rights are when these eligibility factors are evident. Those who failed simply did not know the rights in sufficient detail and/or failed to offer advice that was convincing. The eligibility factors are that the employee, regardless of sexual orientation, is matched with a child for adoption by an approved adoption agency; having worked continuously for the same employer for 26 weeks leading into the week in which they are notified of the match with a child for adoption (the 'matching week'). The right to adoptive leave, again regardless of sexual orientation, covers individuals who adopt, or one partner of a couple where the couple adopt jointly. There are two types of adoption leave: i) 26 weeks ordinary adoption leave, and ii), immediately followed by 26 weeks additional adoption leave, giving a total of up to 52 weeks. Most adopters will be entitled to Statutory Adoptive Pay (SAP) from their employer on a similar basis to that governing Statutory Maternity Pay. SAP is payable for 39 weeks. The rate of SAP is the same as the lower rate of Statutory Maternity Pay. Other such rights are contained in the Paternity and Adoption Leave (Amendment) Regulations 2008. Dr Tony Dundon Chief Examiner Registered charity no: 1079797 14