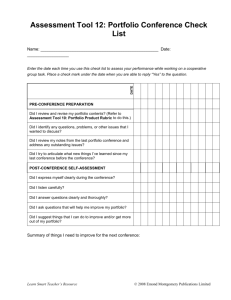

Common Stock portfolio Management Strategies

advertisement