Structural Features of Language and Language Use

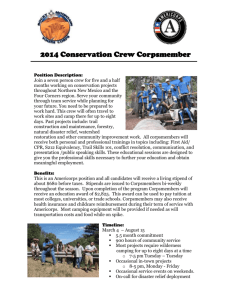

advertisement