Merit pay - Conseil central de Lanaudière-CSN

advertisement

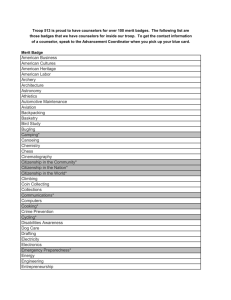

Merit pay Examination of the proposal made by the Standing Committee on Public Accounts of the Parliament of Canada Review of the theory, research and practice March 2003 Merit pay TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTR0DUCTION..................................................................................... 1 2. MERIT PAY: WHAT IS IT? ...................................................................... 1 3. MERIT PAY: THEORY AND ORIGINS...................................................... 3 4. CONSIDERATIONS IN IMPLEMENTING MERIT PAY .............................. 6 5. PERFORMANCE .................................................................................... 12 6. DETERMINING INCREASES IN PAY ..................................................... 15 7. DISCUSSION........................................................................................ 18 8. CONCLUSION....................................................................................... 20 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................................................... 21 i Merit pay 1. INTRODUCTION At the recommendation of the Canadian Parliament’s Standing Committee on Public Accounts, the Treasury Board Secretariat is asking for proposals for a feasibility study on the implementation of a system of merit pay for unionized employees in the federal public service. The Secretariat is also asking for information on the costs and potential benefits of such a system. The terms of reference indicate that the study is to pay special attention to systems based on individual appraisals. In this context, we will focus on two aspects of merit pay. We begin by looking at what merit pay is, and then analyse and comment on it, including a review of the literature. 2. MERIT PAY: WHAT IS IT? To answer this question, we consulted the findings of three U.S. experts recognized as such in both academic and business circles: Robert L. Heneman, author of Merit Pay: Linking Pay Increases to Performance Ratings, published by Addison-Wesley in 1992; and George T. Milkovich and Jerry M. Newman, co-authors of Compensation, Seventh Edition, 2002, published by McGraw-Hill Irwin. Heneman defines merit pay in this way: At a very specific level, merit pay can be defined as individual pay increases based on the rated performance of individual employees in a previous time period. Under this specific definition, salary increases are granted on the basis of a subjective judgement of employee performance in a previous period of time. (6) Milkovich and Newman give the following definition: Wage increase granted to employee as function of some assessment of employee performance. Adds to base pay in subsequent years. (291) Two features are common to both definitions: the individual nature of merit pay, and performance ratings or assessment. These are the fundamental characteristics of this system of pay. Widely used in the United States, merit pay is a form of compensation that dates back to the early 20th century. In 1992, when Heneman’s book was published, he estimated that 80% of companies in the United States used merit pay. He added that in the public sector, though, 1 Merit pay Public sector employees tend to show less frequent use of merit pay plans. (8) By 1989, merit pay was used by 37 of the 50 states, compared to only 27 out of 50 in 1975. Looking at governments, or overall public administrations, merit pay was used by 48%. There seems to be a broad consensus among U.S. employers on the effectiveness of merit pay. Designed to improve performance and control rising payroll costs, business surveys indicate that it is perceived as effective. The widespread use made of it can also be seen as a reflection of this perception. In the past 25 years, however, many studies have been done by academics as well as by government agencies, such as the U.S. General Accounting Office, to evaluate merit pay more rigorously. All this research tends to point to the same conclusions: “success [in improving employee performance] is moderate,” according to Heneman, p. 10, or again: “does not achieve the designed goal: improving employee and corporate performance.” (Bassett, Compensation and Benefit Review: March/April, 1994, in Milkovich & Newman, 310) In 1991, the U.S. government’s Office of Personnel Management mandated the Committee on Performance Appraisal for Merit Pay, composed of academic experts and chaired by Milkovich himself, to do a vast study to help the government review the merit pay system for mid-level managers. It is worth citing what the experts’ committee had to say about the results of using merit pay on performance (National Research Council, 1991): Researchers in the applied tradition concentrate on the appraisal system and how it functions to serve organizational ends. On the basis of the evidence in the applied tradition, the committee presents two major findings. There is some evidence that performance appraisals can motivate employees when the supervision is trusted and perceived as knowledgeable by the employee. There is evidence from both laboratory and field studies to support the assumption that the intended use of performance ratings influence results. The most consistent finding is that ratings used to make decisions on pay and promotion are more lenient than ratings used for research or feedback. (NRC, 3) The committee added: 2 Merit pay Our reviews of performance appraisal and merit pay research and practice indicate that their success or failure is substantially influenced by the organizational context in which they are embedded. (NRC, 4) At first glance, it would seem that the use merit pay has limited impact on improving performance, and that it is dependent on organizational considerations that can influence its effectiveness. 3. MERIT PAY: THEORY AND ORIGINS This section looks at various aspects of merit pay. Generally speaking, this method uses “standards” that are benchmarks for appraising an individual’s performance. Once this appraisal is done, the individual receives an increase in pay, or perhaps an increase in the form of benefits. The increase may be either a percentage or a flat amount. Finally, the increase may be rolled into the employee’s basic pay, or paid as a lump sum that is not incorporated into the basic rate of pay. So merit pay is flexible, multi-faceted and complicated to administer, as we will see. Merit pay is based on a certain number of theories taken from social sciences as well as empirical research using observation and measurement of results obtained by organizations using this method of remuneration, or illustrated by case studies. The theories are for the most part borrowed from economics and psychology. Briefly, the theory taken from psychology states that motivation and aptitude are the fundamental determinants of performance: Motivation and ability are the primary determinants of performance. (Heneman, 24) This theory suggests using individuals’ expectations to motivate them with attractive measures to which they attach value. For instance, using merit pay as a way to satisfy expectations, an individual can be motivated by accurately measuring his/her performance. Assuming that higher pay is an important objective for the individual, establishing a clear link between pay and performance is a way of creating opportunities for that individual to improve his/her performance. One could say that the organization relies on a “virtuous circle.” 3 Merit pay Psychology also indicates that behaviour, including performance, is determined by its consequences. In pay, this implies establishing a clear link (contingency) between behaviour and reward, and to do so it is necessary for an organization to make clear what the desired performance is and the fact that the value of raises in pay will depend on performance levels achieved, while ensuring that an appropriate period of time is allowed for achieving the desired performance. As well, psychology shows that it is necessary to take into account the relationship between an individual and his/her co-workers, in part to ensure that the efforts required to attain desired performance levels are fair – a perception that is very important in establishing the method’s credibility. Finally, psychology contributes the idea that achieving goals is a source of motivation in and of itself. In this respect, merit pay has to set specific goals that are accepted by employees as challenges, and the amount of pay must then vary in accordance with the level of difficulty associated with the goals and the results achieved. Moreover, the goals and the raises in pay should be determined simultaneously so that the parameters at the outset are clearly defined. Economic theory contributes the notion of the marginal productivity of labour, which measures the number of additional units of production that the addition of one labour unit brings (a measure of economic performance), in light of additional costs incurred and ultimately profitability. It is also the source of the theory of implicit contracts, summed up in the saying, “A fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work,” which implies that performance must be measured and not assumed (Heneman, 38). Merit pay must take into account factors that lie beyond individuals’ control and satisfy the “efficiency” criterion for pay rates that is generally founding the labour market. This approach to pay allows an organization to reduce staff turnover and limit the tendency to lax performance on the job. In short, it is a method of pay based on people’s behaviour and designed to motivate them. The whole method therefore relies on a combination of performance and reward, meaning that very close attention must be paid to the notion of performance. It would seem that the relationship between pay and performance is in fact solidly established. Heneman identified 42 empirical studies on this question covering 31,081 individuals, 67.9% of whom came from professional, management or scientific circles. He concludes: 4 Merit pay In some 40 of 42 studies that looked at the relationship between pay and performance in organizations with merit pay, there was a positive relationship between current merit increase and previous performance. (Heneman, 47) He adds: The actual positive relationship between pay and performance appears to be robust. (Heneman, 47) He qualifies the term “robust,” however, by adding that: The magnitude of the relationship between pay and performance in these studies is not large. (Heneman, 48) From this he concludes: In summary, the perceived relationship between pay and performance under merit plans appears to be moderate. (Heneman, 48) Although these studies were reviewed and analysed ten years ago, they still provide revealing empirical evidence of what this method can do. The conclusions cited above are still just as relevant: the use of merit pay has a limited impact on employees’ performance. But this does not mean that it is no longer of interest to organizations that favour this approach. For according to Heneman, it is still true that: The rationale behind merit pay is not the product of idle speculation. Instead, the concept of linking pay to performance is well grounded in theories form economics and psychology. Moreover, the tests of these theories, which have been conducted through empirical research, have for the most part, been supportive. In short, the rationale behind merit pay has been clearly established. (Heneman, 58) The theoretical considerations and the rationale for merit pay are convincing, according to Heneman. What remains to be tested is its implementation in an organization. Ultimately, results are rather modest, and the implementation phase is crucial, says Heneman, if the method is to really achieve the organization’s objectives: The entire merit pay process must be carefully managed for merit pay to have the desired results. (Heneman, 58) 5 Merit pay Based on their review of the literature, Milkovich and Newman conclude: Although there are exceptions, generally linking pay to behaviors of employees results in better individual and organizational performance. (Milkovich & Newman, 292) One of the influential critics of this idea of individual performance appraisal is Edward Deming, the leading expert in continual improvement and total quality management. As Milkovich et Newman report: …[Deming] … launched an attack on appraisals because, he contended, the work situation (not the individual) is the major determinant of performance. » (Milkovich & Newman, 355) 4. CONSIDERATIONS IN IMPLEMENTING MERIT PAY In the discussion so far, we have seen which theories underpin merit pay and noted the limits identified through empirical research. In his conclusion, Heneman warns practitioners about the need to implement merit pay carefully in order to properly control the expected results. The first consideration is economic: merit pay must first be implemented during a period of price stability. Periods of either rising or declining product and services prices can make the feasibility of merit pay difficult.» (Heneman, 64) A period of price volatility can undermine the incentive value of merit pay, because it makes it hard to properly adjust merit pay increases to variations in prices. Just think of what would happen if the raises paid didn’t keep up with variations in prices. The second consideration is the need to ensure that the organizational setting or institution is in favour of merit pay. One of the findings clearly shows that the setting influences the conditions of implementation: 6 Merit pay … merit pay is used more frequently in the service sector than in the manufacturing sector. (Heneman, 69) Research indicates that this finding stems from the fact that it is easier to assess performance in the service sector. At first glance, therefore, it might seem that the government sector is well-suited to the introduction of merit pay. But the research points to the conclusion that it is harder to introduce merit pay in the public service sector than in the private sector. Perry (1976); Rainey (1979); Silverman (1983); and Scott, Hills, Markham, and Vest (1986) describe some of the situational characteristics found more often in the public sector than in the private sector, which limits the effectiveness of merit pay plans. These constraints include among other things, limited merit pay budgets, limited discretion on merit pay decisions, accountability to conflicting constituencies and a long history of pay based on longevity rather than performance. These constraints, which have led to limited success of merit pay plans in the public sector (Heneman, 70) Howard Risher, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, examined the U.S. federal government’s experience with merit pay, and came to the following conclusions: Merit pay has been tried by many public employers including the federal government. The track record is not a good one. In some public agencies, attempts to introduce merit pay almost trigger an armed revolution. One of the reasons that merit pay has not been accepted in government is that it has been used as a reason to deny increases to poor performers. In contrast, in the corporate world the emphasis is on recognizing and rewarding the better performers with above average. (Risher, 334) It is therefore very important to examine the institutional environment and the organization’s objectives in introducing merit pay. Note as well that between 1979 and 1989, merit pay only affected between 10% and 16% of unionized employees in the United States. An employee’s degree of autonomy in his/her work is fundamental: 7 Merit pay ... an employee must be responsible for performing a whole piece of work. ... a distinct start and finish to the service being generated by the employee, ... to have a noticeable impact on performance. (Heneman, 81 and 82) To this should be added the trust that prevails in the organization, and its human resources management practices. In a very detailed table, Heneman lists the institutional arrangements that make merit pay more or less feasible. (Table 3-2, p. 85) Despite these reservations, if the government considers that it should proceed, there are an impressive number of considerations, limitations and precautions that influence the feasibility of merit pay. 8 Merit pay Institutional Arrangements Contributing to the Feasibility of Merit Pay Merit Pay More Feasible Under these conditions Service Sector Private Sector Middle stages of organizational life cycle Flexible specialization technologies Competitive culture Non unionized Moderate base rate Well-defined job characteristics High discretion in work performed Low politics Merit Pay Less Feasible Under these conditions Manufacturing Sector Public Sector Early or late stages or organizational life cycle Mass production technologies Egalitarian culture Unionized High or low base rate Poorly defined job characteristics Low discretion in work performed High politics When the federal government is considered in light of the institutional arrangements favouring the introduction of merit pay, it is clear that most of the conditions are absent. Of course part of government’s mission involves by definition the delivery of services comparable to the private sector’s. However the role of many departments, including some of the most important, is to redistribute national revenue: this is the case with Finance, or Human Resources Development Canada, which administers transfer payments to the provinces and pays benefits to individuals (Old Age Security, Employment Insurance). Other departments offer consulting services or grant programmes for individuals or business (research), and yet others are control or collection agencies or departments (revenue, customs, public security). In short, government is a complex organization with numerous activities and ultimate purposes. It is virtually impossible to find as large an organization in the private service sector. Furthermore, the federal government is organizationally mature, its operations regulated by standards and fundamentally subject to the authority of parliament. The government’s organizational culture refers to egalitarian standards, because “opportunities” are governed by the concept of merit, and pay progression is generally the same throughout the country, depending in many cases on the length of service. The performance of work is, at first glance, hierarchical and clearly supervised. Many jobs offer little discretion in the performance of the work, and little room for initiative and autonomy. For a number of reasons (staffing, regional equity, nature of duties, specialization, unionization), pay levels, especially basic pay levels, are certainly higher than in many 9 Merit pay organizations or businesses in the private service sector. All this indicates that merit pay is not an obvious solution. And in fact, the National Research Council’s work in the United States (1991) found that merit pay in the federal government was ... a matter of continuing controversy and periodic amendment. (NRC, 160) There are many reasons for this. But noting that merit pay was developed by private sector organizations, the NRC considered that there was a problem related to the very nature of merit pay and organizational differences between the private sector and the federal government. The federal government faces special, if not entirely intractable, problems that work against any easy transferability of private-sector experience. (NRC, 160) The NRC added: Where private-sector practice relatively easily accepts manager-employee exchanges about performance objectives, both individual and organizational, such a practice in the public sector could be perceived as opening the civil service to partisan manipulation. (NRC, 161) In the opinion of NRC’s research team, merit pay in the private sector is more successful in what it called “high-commitment organizations” (161), where the following conditions make appreciable results possible: ± merit pay is an integral part of a comprehensive management system; it is not an add-on, but a systemic component that underpins and complements the organization’s management philosophy; ± there is an emphasis on the need for managers to be discrete and flexible in fulfilling their responsibilities; ± the organization and its employees share common values, and there is a high level of trust; 10 Merit pay ± the standards for success are valued by the organization as a whole as well as by the individuals in it; ± and finally, the turnover in management is low. It is not at all obvious that these conditions are met in the federal government’s administration. More could be said, but on the face of it, the values of public managers and of government itself are not all that close to those of the private sector, where competitive values in particular are a motivation for many employees and clearly favor the implementation of merit pay. Moreover, can such a value be introduced in the public sector without introducing dangerous trends such as discrimination among employees, or individual conduct influenced by the lure of power and personal gain that is incompatible with the mission of a public administration? It’s very risky. To return to the evaluation of merit pay in the U.S. federal government, the internal assessment by managers raised a paradox that is worth noting: ... a study by Clark et Wachtel (1988) ... In this study of 4,000 federal managers 90 percent favored the concept of merit pay; however, 74 percent felt that the current system was unfair. (Heneman, 88) This section suggests that the introduction of merit pay, particularly in the public sector, is not obvious. The U.S. experience in this regard shows that at root, the concept itself, stemming from the competitive environment and management philosophy of the private sector, and more especially the U.S. private sector, does not correspond to the characteristics of the public sector. Hence the need for costly adjustments, failing which the consequences are unintended adverse effects on employee motivation, their perception of the fairness of merit pay and their trust in it. We will come back to some of these points in our conclusion. 11 Merit pay 5. PERFORMANCE In this section, we will look more specifically at the central concept in merit pay, namely performance and the performance appraisal process. The definition of performance can vary from one organization to another. There are, however, some points in common: it is focused on the individual, and is related to certain characteristic roles and duties deemed essential by management in the organization. So from one organization to the next, there are similarities and differences. It is generally defined in terms of standards that vouch for its measurement. The textbooks call these: - absolute standards: 1) expected and actual outcomes; 2) individual personality traits; 3) behaviour, i.e., the way in which a person performs his/her work and duties. These are so to speak the general standards valued by the organization. - comparisons: 1) ranking an employee in relation to the one who has contributed most to the organization; 2) in smaller organizations, an employee is frequently ranked in relation to each of the other employees. We can anticipate that there will already be a certain amount of subjectivity in the standards selected, which the research tries to control for. For instance, it seems that it is possible to reduce subjectivity by linking the standards to an employee’s job description or the strategic corporate mission, or by using feedback techniques to better define and delimit the standards. Furthermore, since the standards are used by an individual to assess an employee’s performance, there is again a substantial margin of subjectivity. 12 Merit pay According to specialists like Heneman, Milkovich and others, the advocates of merit pay have to make sure that the measurement of performance and performance appraisal meets criteria that make it less subjective. For instance, these authors recommend: - that performance should measure properly what is wanted, that there must not be confusion about the source of merit pay (such as giving both a promotion and raise in pay at the same time, or making partial use of seniority as a criterion for determining a raise, or using merit pay to retain high-performing employees, or trying to “reward” “standard” performance rather than the best performance); - that to allow adequate assessment, the content of performance be clearly defined, notably with respect to the relation between the job and the standards; - that appraisals be consistent over time; - that appraisals be accurate, i.e., that the outcome of the appraisal be fairly related to performance; - that appraisal errors such as the following be minimized: . the halo effect: when the appraiser tends to rate someone highly because of the predominance of a specific characteristic that the appraiser favours; . the horn effect: the opposite of the halo effect; . first impressions: when the appraiser develops an opinion at the very start of the process that affects the results of other subjects evaluated subsequently. There are other biases to be avoided as well, such as appraisals focussing on performance results towards the end of the period instead of performance over the entire period; mistakes due to being very strict or very lenient, or dropping both extremes; and the danger of repeating previous mistakes in the annual appraisal. As we can see, appraisal is subject to numerous biases. The impact of these biases has been examined, and Heneman did a statistical estimate of their impact on the validity of assessments: Even though different methodologies were used, the results were very similar and suggest that the upper bound of validity performance ratings is about .60, with a value of 0 representing no validity and a value of 1.00 representing perfect validity. What this value of .60 indicates is that about 36% of the 13 Merit pay variability in the indicators being used to assess validity is due to performance ratings. ... it suggests that about 64 percent of the variability in standards being used to assess validity are due to factors other than performance ratings. Therefore, most measures of performance are less than perfect representation of the employee’s ultimate performance contribution to organization. (Heneman, 131, 132) To control variability in results, both Heneman and Milkovich and Newman suggest ways of improving their reliability. Some of these have already been mentioned here: - rigorous, exact definitions of standards – ones that do not lend themselves to overinterpretation, that are clearly related to performance, to the organization’s mission and to the duties set out in job descriptions; - employee involvement in the process; - training for appraisers aimed at achieving a more uniform understanding and application of the appraisal system; - an appraiser’s “diary” for noting the evolution of the assessed employee’s performance as it happens; - developing appraisers’ skills, improving their abilities and accountability; - establishing guidelines for appraisals; - offering employees an opportunity to understand and influence decisions stemming from the appraisal. All these suggestions are demanding, in that an organization using merit pay has to have the resources required to try to guarantee the process an acceptable level of credibility. 6. DETERMINING INCREASES IN PAY Once the process is established and the appraisal done, its credibility in the eyes of employees will, despite all the precautions taken, depend partly on the resulting increases in pay. This raises the whole question of determining the size of total payroll that the company or 14 Merit pay government considers appropriate for the company or government, as the case may be, given the economic and financial constraints underlying any pay policy. Merit pay specialists consider that to produce results and be accepted by employees, the system requires the creation of something they call “Just-Noticeable Differences” (JND): The concept of “Just-Noticeable Differences” refers to the minimum pay increase that employees would perceive as making a difference with regard to their attitudes and behaviours. (Heneman & Ellis, 1982, p. 149) The “minimum” aspect of the pay increase is important, because: If merit increases are not large enough to have a JND, they may not produce increases in future performance. (Heneman, 158) This refers back to concepts borrowed from psychology that we examined earlier. Defining a difference that is perceived by the employee as sufficient motivation to improve his/her performance creates a serious problem for the distribution of the pay budget, if only because of variations in individuals’ perceptions of what the “Just-Noticeable Differences” should be. Generally speaking, once the performance appraisals are completed, the distribution of the pay budget is determined by applying a chart of pay increases based on performance levels. Note that in the two examples given here, there is no pay scale per se. This does not mean that such a scale is not used in the organization. There are usually minimum and maximum rates of pay that are used as guidelines for compensation, and there may also be a median salary, as in this illustration: 15 Merit pay - maximum $50,000 - median $45,000 - minimum $40,000 From here, pay is adjusted on the basis of the chart of increases. INCREASES CHART Example 1 (Milkovich, Newman) Level 1 2 3 4 5 Performance Exceptional Very Satisfactory Somewhat Unsatisfactory satisfactory Increase 7% unsatisfactory 6%/5% 3%/4% 1%/2% 0% Example 2 The chart in this example is more complex. It first ranks employees into groups – quartiles, in this case – based on the quantified results of their appraisal, or on an employee classification system. It also takes into account the performance level achieved by employees in each quartile. So an employee could be classified in the second quartile and receive an individual performance rating of “fully satisfactory,” while another employee in the same quartile might be rated as “needs improvement.” Finally, the chart indicates the frequency of performance appraisals. For instance, an employee classified in the second quartile who obtains a performance rating of “fully satisfactory” will be reassessed between 15 and 18 months after the first appraisal. An employee may also move from one quartile to another, usually on an annual basis. This chart is taken from Heneman (174). 16 Merit pay Complex Merit Guide Chart (Table 5.5) Performance Levels Position in range Unsatisfactory (Quartile) 4th rd 3 nd 2 st 1 0% 0% 0% 0% Needs Fully Above Clearly Improvement Satisfactory Expectations Outstanding 0% 3-5% 5-7% 7-9% 15-18 M 12-15 M 9-12 M 0-3% 5-7% 7-9% 9-11% 15-18 M 12-15 M 9-12 M 9-12 M 0-3% 7-9% 9-11% 11-13% 12-15M 9-12 M 9-12 M 6-9 M 0-15% 9-11% 11-13% 13-15% 9-12M 9-12 M 6-9 M 6-9 M M = Months This chart has four dimensions. First, employees are placed in a quartile, which generally corresponds to job duties and responsibilities – it’s more or less a classification “system.” Next, performance is rated at one of five levels. Once this is done, the rate of increase leaves the employer some discretionary leeway: for instance, an employee in the second quartile who obtains a “fully satisfactory” performance rating would receive an increase ranging from 7% to 9%, meaning that a number of employees in the same classification (quartile) with the same rating could receive different increases. Finally, to complete the system, the length of time before the next appraisal date varies, depending on the classification (quartile) and performance level achieved. Before concluding this section, note that these charts are applied in a framework of controlling the payroll, which may entail periodic changes in the parameters used to determine total annual payroll increases so as to reflect the financial situation of the business or organization. Another way of controlling the total payroll would be to pay the amounts resulting from the application of such charts without including them in basic pay. 7. DISCUSSION 17 Merit pay The theory and teaching presented in textbooks and the research literature clearly indicate that merit pay is complex and demands a series of precautions to ensure that it works and produces the main desired result, i.e., that it encourages employees to constantly improve their performance on the job. Although we have reviewed all that has been written on merit pay in the United States, given the intensive and extensive use made of it there, it is still relevant to examine it in relation to public and private organizations in Canada. Anyway, the research is repeated in Canadian publications. The reference paper prepared by the Treasury Board Secretariat doesn’t make clear what the Standing Committee on Public Accounts’ fundamental objective is. What does this recommendation seek to do? We have already seen that specialists who have studied merit pay at length have pointed out that an organization must have a clear goal, and that in most private-sector businesses, this goal is to recognize and “reward” the best employees, the ones whose performance is superior. An examination of the situation in the public sector in the United States shows that in practice, this objective is not achieved, notably because of the institutional framework. What is more, one of the conclusions reached by the Experts’ Committee of the National Research Council at the end of its study was that: In order to motivate employees and provide them incentives to perform, a merit plan or any pay-for-performance plan must theoretically (a) define and communicate performance goals that employees understand and view as doable; (b) consistently link pay and performance; and (c) provide payouts that employees see as meaningful. These conditions seem straightforward, and the notion of pay performance thus becomes deceptively simple. Our reviews of research and practice indicate, however, that selecting the best pay-forperformance plan and implementing it in an organizational context so that these conditions are met is currently as much an art as a science. We cannot generalize about which pay-for-performance plans work best – especially for the federal government, with its considerable organizational and workforce diversity. (NRC, 165) Considering, on the one hand, that conditions of pay for employees in the federal public service are governed by collective agreements, and that on the other hand, the diversity of federal government activities is far greater than that of even the largest companies in the private sector, the conclusions of the NRC experts provide a very serious warning about the feasibility of such a proposal. 18 Merit pay In this paper, we have looked at the multiple facets, the difficulties in implementation and the precautions to be taken to minimize mistakes in both the design and application of merit pay. These are some of the important points to be considered: a) Merit pay individualizes pay increase and pay levels for the same or comparable jobs – something that does not correspond to the values of equality and fairness promoted by unions. b) It is a pay method that is not based primarily on workers’ concerns, namely protecting their purchasing power, pay equity and general increases in levels of pay. c) It is a method of pay that is ill-suited to the realities observed in workplaces – for example, how is performance defined in workplaces that are governed by standards set by all kinds of legislation and regulations, such as correctional services, or food inspection, or customs? In these types of work, employees’ initiative is limited and government objectives are prescribed by law, making the situation very different from what exists in the private sector. d) The administration of merit pay in such a huge organization would require considerable efforts and strict controls. The employer would have to take steps to avoid bungling, take into account very different diverse situations and do its best to achieve a certain degree of homogeneity and consistency in the decisions made by thousands of managers in order to ensure the reliability of merit pay. All of this with the goal of trying to get employees to see merit pay in a positive light and maintain an acceptable level of trust. The task is demanding, and indeed hard to accomplish. In this regard, here is what Brown has to say (1990): For incentive pay, they are the costs of measuring output and setting up (and updating) the relationship between prices and pay. For merit pay, there are the costs of obtaining sufficiently careful ratings from supervisors and of convincing workers that these ratings should be taken seriously. (180-5) 19 Merit pay CONCLUSION Merit pay is not at all consistent with union principles, which are based on equal treatment, an open, transparent pay system and pay increases determined in accordance with workers’ needs, i.e., to preserve and improve their purchasing power. Tying pay solely to individual performance, as recommended by the experts in designing and implementing an effective merit system, introduces a significant risk for both outcomes and for the treatment required to administer the system. Pay increases would vary from one period to another, and in an organization whose labour force is largely unionized, it could expected that this would rapidly cause dissatisfaction and even resentment. Information circulates in a union organization; in fact, a union has a duty to spread and share information, because it is absolutely crucial to decision-making, especially during collective bargaining. Such a system would certainly result in differences in pay within our union. There are 51 penitentiaries across Canada, and more than 5,500 members in our union. There would be hundreds of supervisors doing performance appraisals, and given the difficulties inherent in administering this system, we would most certainly be swamped with demands for reviews of appraisals. Apart from such “procedural” considerations, we have already pointed out a workplace regulated by standards as strict as those in correctional services does not lend itself to the implementation of merit pay. The review of the literature, the evaluation of the experts whose work we consulted and the National Research Council’s conclusions regarding the experience in the U.S. federal public service all lead us to conclude that we cannot agree to modifications or changes in the principles and practices that now govern the pay structure in the federal public service. From its earliest days, the labour movement has never wavered from a fundamental principle on pay that has served workers well: to keep wages out of competition. Merit pay introduces a factor of competition among workers within a given company or organization that is inevitably harmful to collective interests and solidarity. Claude Rioux Economist for the Confédération des syndicats nationaux Document discussed and adopted by the UCCOO-SACC-CSN National Committee 20 Merit pay BIBLIOGRAPHY Heneman, Robert L. (1992), Merit Pay Linking Pay Increases to Performance Ratings, AddisonWesley, 298 p. Milkovich, George T. and Newman, Jerry M. (2002), Compensation, Seventh Edition, McGraw Hill Irwin, 682 p. National Research Council (1991) Pay for Performance: Evaluating Performance Appraisal and Merit Pay, National Academy Press, 210 p. Ehrenberg, Ronald G. (1990) “Do Compensation Policies Matter?” Industrial Labor Relations Review, Vol. 43, Special Issue. pp. 3-5 to 12-5 Brown, Charles (1990), “Firms’ Choice of Method of Pay” Industrial Labor Relations Review, Vol. 43, Special Issue. pp. 165-5 Schwab, Donald P. and Craig A. Olson, “Merit Pay Practices: Implications of Pay-Performance Relationship” Industrial Labor Relations Review, Vol. 43, Special Issue, p. 237-5 Institut de recherche sur la rémunération (1996), Rémunération variable. Description et tendances, Vol. 1, Québec Risher, Howard (1999), “Are Public Employers Ready for a “New Pay’’ Program?” Public Personnel Management, Vol. 28, No. 3, p. 323 Thériault, Roland and Saint-Onge, Sylvie (2000), Gestion de la rémunération. Théorie et pratique, Gaétan Morin, 780 p. 21