Teaching the use of research: limitations of research, constraints on

advertisement

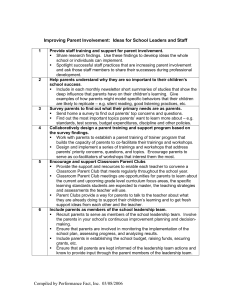

Teaching the use of research: limitations of research, constraints on its use. Sandy Oliver The Social Science Research Unit has a well established programme of policy relevant research. This attracted funding from the Department of Health in 1996, not only to extend a programme systematically reviewing literature about the effectiveness of health promotion services, but also to engage practitioners and policy makers in the process of using research. For this we conducted a series of workshops designed to support ‘Promoting Health After Sifting the Evidence’ (PHASE). This article tells the story of these workshops, and considers the limitations of research and the constraints experienced by potential users of research. In order to plan health promotion services, commissioners and providers of health promotion services ask fundamental questions about the value of the work they support. Which interventions are effective and how do we know? What are the most efficient ways of finding the most reliable evidence? Getting the answers is hindered by the difficulty of accessing relevant and appropriate research evidence and the lack of skills to judge quickly whether these are reliable and applicable to current, local needs. With the PHASE workshops we aimed to a) raise awareness of the need to base health promotion interventions on reliable evidence about their effectiveness; b) disseminate sources of effectiveness data; and c) improve skills in critical appraisal amongst those working in the field of health promotion. From the workshop participants we learnt about a variety of other barriers that needed to be overcome to facilitate the use of research in the decision-making process. 1 Planning teaching with workshop participants Building on prior experience (Milne et al 1995; Milne and Oliver, 1996), we planned a series of five PHASE workshops in discussion with potential participants. Meetings discussed the potential relevance of critical appraisal to the work of purchasers and providers; the choice of topics and practical problems on which to centre the learning; and opportunities for prospective participants to take leading roles in the delivery of the workshops. Workshops focus on research reflecting health promotion specialists’ interests in peer-led programmes and community development. However, finding sufficient research papers which would satisfy workshop participants was hampered by the dearth of sound evaluations of effectiveness in health promotion. Another constraint was the importance paid by many health promotion providers to criteria such as the degree of community participation in judging the quality of interventions (Speller et al. 1997). Again, the literature here is not well-developed. The series of workshops addressed the following research areas: an investigation of the diffusion of an anti-smoking programme through a school system; a trial of peer sex education in schools; a randomised controlled trial of AIDS education interventions for homosexually active men; a systematic review of smoking cessation programmes for pregnant women; and a proposal for evaluating an accident prevention intervention aimed at mothers with young children. Materials were sent to participants one week in advance of the workshop and contained an introduction to the concept of evidence-based health promotion and the paper for appraisal during the workshop. The workshops were set up as interactive sessions designed to learn about each others’ ideas and expertise. Each workshop lasted 4 to 5 hours and was divided in four parts: (1) a plenary session which introduced key concepts for learning from reports of feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness in health promotion; (2) critical appraisal of a research paper in small groups; (3) participants sharing the discussions and 2 conclusions from their small group work in a plenary session and considering the opportunities to apply critical appraisal skills in their work; and, finally (4) a short evaluation session, both verbal in plenary and written. Each workshop was delivered by a team of researchers and health promotion purchasers and providers. Facing a challenge Despite efforts to adapt the workshops to suit health promotion needs with considerable help from health promotion specialists in both the development and delivery of the workshops, participants still faced serious hurdles before they were ready to consider using effectiveness studies to plan their work. Before attending the workshops, most participants had, in the course of their work, asked questions about the availability, acceptability and effectiveness of particular health promotion approaches and programmes, but only half of them had found an answer; usually by referring to the opinions of their immediate colleagues, internal reports or personal experience. This reliance on professional opinions rather than published sources of information about effectiveness of health promotion is\widespread (Shadish and Epstein 1987; Bonell 1996). Many health promotion providers either did not have access to, or chose not to use, sources of information which specialise in reliable evidence of effectiveness, such as the Effective Health Care Bulletins produced by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination in York and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews produced by the Cochrane Collaboration. Some workshop participants were sceptical of Effective Health Care Bulletins as an appropriate and useful source of information for health promotion with their emphasis on the use of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Even when participants would like to address the issue of effectiveness of health promotion, they could be 'bowed down trying to 3 demonstrate the effectiveness of what they’re doing', and claimed 'research is actually the last thing used to make a decision in the current political climate'. A recurrent theme of discussion throughout the series was the desired balance between building the research skills of practitioners and commissioners and their acquisition of research-based information. Ironically for a profession espousing the empowerment of others, many of them rejected the opportunity to empower themselves with new skills. They would have preferred to be told what was effective rather than apply their own judgement to a report, 'People want critical appraisal done for them, not to do it themselves - some people struggle with the conceptual understanding and the statistics.' Nevertheless, some rose to the challenge, 'I thought I would learn about good practice, not the process of how to find good practice - neverthe less this is beneficial and I think I learned this. I would have liked to come to all five...' Needs for research training Some participants were very clear about their needs for support and information when working towards effective health promotion. Some wanted information on what studies/ papers are available, on current work in their particular topic area, and advice on what they were proposing to do - was it effective or how could they make it more effective? Some wanted discussion, 'I think most health promotion staff have skills to appraise an article. What is needed is an overview of evidence in specific areas eg smoking... a consensus on what can be taken from it and therefore identified programmes.' And others wanted support in developing and evaluating their own work. 4 Some participants wanted to share their newly acquired skills with their colleagues. Others planned to use the critical appraisal guidelines for their own report writing. This may lead to more clarity about the research questions and conclusions of internal reports, which is particularly encouraging because health promotion has a wealth of 'grey literature' evaluation reports which are often not widely or systematically disseminated, and hence are difficult to obtain for inclusion in for example, systematic reviews. Barriers to a concerted solution Just like the individual behaviour change interventions for healthy lifestyles, any individual changes in attitudes towards using research are unlikely to reap real benefits without facilitative changes in the working environment. The opportunity for workshop learning to improve effectiveness in practice was impeded by the organisational structure of the NHS internal market, a structure ultimately aimed at improving services. The need for services to secure funding from commissioners proved to be a barrier to open discussion in workshops. The fact that some providers were reluctant to share their ideas with competing provider units is yet another barrier to sharing each others’ resources and expertise which needs to be addressed by purchasers and providers together. However, learning together is possible and can be very productive, as was experienced within the relaxed atmosphere of a subsequent specially commissioned PHASE workshop held outside London, where participants knew each other and were used to meeting regularly. They particularly valued: In addition to potential barriers to open discussion, the pressures imposed by contracting cycles within the NHS were brought forward as a problem to using research in the decisionmaking process. Participants discussed these barriers and the need for providing an environment that is conducive to integrating research and practice: 5 '[There is a] time pressure on reading, reflecting, and processing evaluation reports.' '[We need] an environment where evaluation is supported. At the moment all good intentions are hopelessly unrealistic.' '[We need] the time to do it within a contract.' 'People need to know it’s OK to spend a day in the library doing searching properly.' It was clear that a concerted effort was called for involving all those working towards effective health promotion: 'We need to clarify a legitimate role for commissioners in stimulating and funding research. We need to clarify a le gitimate role for providers. And to analyse the relationship between research and practice and the potential for incorporating research into practice.' However, the complementary aim of incorporating research into practice, in other words developing services in a research framework when the evidence is lacking, still seemed a little far-fetched. An important finding was that even enthusiasts of evidence-based health promotion are de-motivated by the lack of support and resources for evaluation and the restrictions imposed by the contracting/commissioning cycle. In an environment that advocates evaluation and using research in the decision-making process, contracts need to allow time for literature searches to inform new projects and for the planning of interventions to include appropriate evaluation. 6 Key messages • Health promotion specialists can develop skills to use research literature, but they need a conducive working environment • Health promotion funders can encourage evidence-based services by allowing time and resources for seeking and appraising literature to inform service planning and by funding interventions with integrated evaluations. • In using research, effectiveness studies need to be integrated with the principles of community development and ‘Health For All’ Note A fuller account of these workshops and other parallel work appears in ‘Using Research for Effective Health Promotion’, edited by S. Oliver and G. Peersman, and published by Open University Press, Buckingham 2001. References Bonell, C. (1996) Outcomes in HIV Prevention: report of a research project. London: the HIV project. Milne, R., Donald, A. and Chambers L. (1995) Piloting short workshops on the critical appraisal of reviews, Health Trends , 27(4):120-123. Milne, R. and Oliver, S. (1996) Evidence-based Consumer Health Information: developing trends in critical appraisal skills, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 8(5): 439-45. 7 Shadish, W.R. and Epstein, R. (1987) Patterns of program evaluation practice among members of the Evaluation Research Society and Evaluation network, Evaluation Review, 11:555-90. Speller, V., Learmonth, A. and Harrison, D. (1997) The search for evidence of effective health promotion, British Medical Journal, 315:361-3. 8