Equity markets and economic development

advertisement

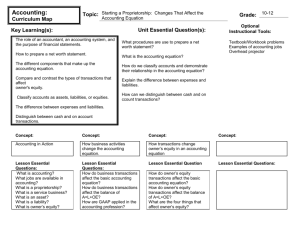

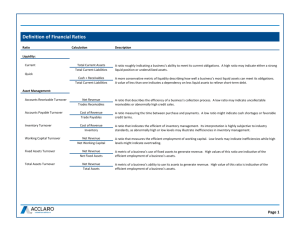

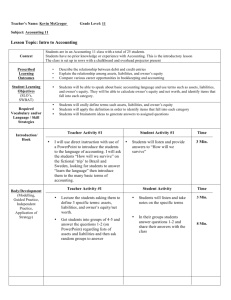

Equity markets and economic development: Does the primary market matter? Andriansyaha,b,*and George Messinisa aCentre for Strategic Economic Studies, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia bMinistry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia This paper examines the role played by primary and secondary equity markets in economic growth. In contrast to standard literature consideringsecondary market indicators, this study integrates both types of market while explicitly acknowledging the role of primary markets. By employinga variety of dynamic panel estimators for 54 countries over the period 19952010, we show that the primary equity market is not an important determinant of economic growth, despite facilitating development of the secondary market. This study also confirms the importance of secondary market activity, such as trading liquidity,as a determinant of economic growth. These results call for a further investigation into the capital-raising function of equity markets in relation to their liquidity function. Subject Keywords:Equity Markets, Primary Markets, Secondary Markets, Development JEL Codes:E44, G23, 016 * Corresponding author. Postal Address: Centre for Strategic Economic Studies, Victoria University, PO Box 14428, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 8001, Street address: Level 13, 300 Flinders St, Melbourne Victoria Australia 3000. E-mail: andriansyah.andriansyah@live.vu.edu.au -1- 1. Introduction While studies in the finance-growth nexus initially focused on relationships between bank-based measures of financial development and economic growth, the impact of marketbased measures on growth has assumed importance. This has been particularly so since the World Bankconference on this issue in 1995 and the publishing of papers presented in a special edition of the bank’s economic journal a year later. In summarizing these papers, Demirguc-Kunt and Levine (1996b)stressed that equity market development is an important determinant of corporate financing choices and long-run economic growth. They argue that the main channelmoving the equity market to achieve economic growth is liquidity that leads to capital accumulation and allocation. This paperargues that the capital-raising function of primary equity markets is in fact the main driver of, and at least as important as, the liquidity function of secondary equity markets for the stimulation of economic growth. In this context, this paper examines the importance of both types of equity markets in an integrated framework. The primary market can be defined as the marketplace where new shares, either from unissued or issued shares, are offered to public investors, either at the initial public offering (IPO) or seasoned equity offering (SEO) market. The new shares may then be traded among investors on a stock exchange(s) where they are listed. This trading marketplace is referred to as the secondary market. An economic consequence of these two markets is on the cash or capital inflows to offering firms. New capital can be raised and then used by the listed firms, but no additional money can flow into the firms from the secondary market transactions. In addition, from a macroeconomics perspectivea transaction on a stock exchange is not considered as an investment, while the selling of new shares at the IPO and SEO markets is (Mankiw 2010). Despite these different market characteristics, economists and researchers tend to only usesecondary market indicators such as market liquidity, market capitalization, composite index returns and volatility as measures of stock market development. They overlook -2- primary market indicators such as the total capital raised and number of listed companies (see for example,Demirguc-Kunt and Levine (1996a),Levine and Zervos (1998), Beck and Levine (2004a),and most recently Lee (2012)). This oversightmay be due to the common understanding of a stock market being mainly a secondary market – as stated in standard textbooks of finance such as Pilbeam (2010, pp. 214-5). Theoretically, functions of the equity market are similar to those of the capital market. Thus, theoretical frameworks that explain why equity market development is related to economic development are mainly the same as those used in the finance-growth nexus. The main functions of the equity market are also summarized byLevine (2005)as similar to those of the financial system, namely: providing capital and efficiently allocating this capital into productive investments; utilizing domestic savings; improving information; effectively monitoring mechanisms of good corporate governance practices; providing risk-reduction mechanisms; and facilitating exchange of financial instruments that representthe ownership of capital.By ensuring that these five functions run well without any friction, Ang (2008) furthermore highlighted that equity markets will lead to long-term growth through two main transmission channels: the capital accumulation channel; and the total factor productivity (TFP) channel. The first channel reflects and refers to the most important function of capital accumulation and allocation, while the second channel mainly refers to the qualitative effects of these functions. Some endogenous growth models have examined stock market developmentas one of the important factors explaining economic growth. For example, by developing the model of Greenwood and Jovanovic (1990), researchers including Atje and Jovanovic (1993)stress that the stock market is an important determinant of economic development, measured either at the actual level or growth rate. Furthermore, they explain that funds will move to profitable investments when better information regarding investment projects is provided. In another study, Bencivenga, Smith and Starr (1996) explain that efficient allocation of resources can only be achieved by reducing the transaction costs of saving mobilization. This is because the -3- liquidity created by efficiency in trading will secure permanent access to the capital invested by initial investors for the financing of long-term and high-return projects. However Bencivenga, Smith and Starr (1996) show that the relationship between the equity market and economic development may be imperfect and therefore unclear. For example, they showed that when there is a decrease in transaction costs, an efficiency or liquidity improvement in secondary equity markets will stimulate an increase in market activity volume.However, when economic agents are only active in the secondary markets and reluctant to invest in a new project (i.e. pure speculative trading), this increasemay have no impact on the level of real activity. Furthermore, Deidda and Fattouh (2002) found that the relationshipmay be non-linear and non-monotonic withthe positive impact of financial development depending on the maturity stage of financial markets. These theoretical frameworks have been supported by many empirical studies that mainly found positive relationships between stock market development and economic growth. Having used a stock market development index developed by Demirguc-Kunt and Levine (1996b)that combined indicators of market size, liquidity, and risk diversification as well as controlling initial condition and other economic and political factors,Levine and Zervos (1996)find evidence of a strong relationship between the two variables of interest. A recent study byLee (2012)shows that causal relationshipis mainly from financial markets to economic growth in cases of the U.S., the U.K., Japan, Germany and France. In fact, the assessment of direction of causality between finance and growth based on the notion of ‘supply-leading’ and ‘demand-following’ of Patrick (1966) has dominated most of the empirical studies. Rather than being ‘caused by’ (in Granger causality sense) as implied in the supply-leading, the demand-following postulates that economic growth will stimulate the demand for financial services and instruments. A recent study of Halkos and Trigoni (2010), for example, shows that there is a long-term relationship between these two notions of causality in 15 European countries. Another study of Rachdi and Mbarek (2011) also provides similar results for some OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation -4- andDevelopment) and MENA (Middle East and North Africa) countries. However, the direction of causality is different; bi-directional causality exists for the OECD economies while demand-following exists for the MENA ones.1 There have also been studies, however, that show opposite results, or at least find no significant relationship between stock market development and economic growth.Singh, A (1997) and Harris (1997), for instance, argue that stock markets may be more beneficial for developed countries, not for developing ones. Singh, A (1997) argues that equity market development in developing economies – that mainly evolve as the result of the financial liberalization – creates more negative effects on their economic development than positive ones. He contends that the TFP channel is more dominant than its capital accumulation counterpart, but this channel, especially through the functions of trading and corporate controls, does not work efficiently so the markets tend to produce speculative market prices and financial-engineered-based (non-organic) growth. He also criticizes the type of investments undertaken by the listed firms that are mostly not in the form of firm-specific human capital. Supporting the argument of Bhide (1993), Singh, A (1997) argues that liquidity has a devastating effect on financial stability because it make the markets more volatile, and eventually affecting the volatility of the exchange rates. Bhide (1993)mentions that the U.S. regulations aiming at increasing market liquidity have negative effects on the governance of listed firms, especially by reducing the role of active stockholding in monitoring managers.Nagaishi (1999) and Chakraborty (2010) principally support the conclusions of Singh, A (1997),arguing that the relationship between stock markets and economic growth in India is not clear and tends to be negative. Nagaishi (1999) finds that stock markets do not contribute to gross domestic savings and the share of financial assets of the household sector, and, in fact, foreign capital inflows potentially create more volatility in 1 Other cross-country studies supporting the notion that stock market development also plays a significantly positive role in economic growth are Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine (1996b), Fry (1997), and Levine and Zervos (1998). Meanwhile, single-country studies among others, are: Gan et al. (2006) for New Zealand; Kaplan (2008) for Turkey; Maysami, Howe and Hamzah(2004) for Singapore; Shahbaz, Ahmed and Ali (2008) for Pakistan; Siliverstovs and Duong (2006) for European countries; and Chaudhuri and Smiles (2004) for Australia. -5- stock prices and the balance of payments. Furthermore, he argues that the substitutive function of stock markets is more dominant in the role of financing private investments, so an increase in public offering in the primary markets does not necessarily boost economic growth. To summarize, the debate about the benefits of the equity markets on economic development has been still inconclusive. While the theoretical studies and empirical findings support the importance of liquidity in secondary markets, the impact of such trading activities on capital allocation in primary markets needs further examination.Therefore, there is still a need to explicitly differentiate the role of the primary market and the secondary market in their relation to economic growth, as well as to empirically test if the latter has positive impacts to the former. This paper attempts to address thesequestions. In terms of differentiating equity markets into primary and secondary markets, to the best of our knowledge there has not been any study examining the different roles of the markets on economic growth. The closest one to our study may be a study of Singh, T (2008). Using the financial interrelation ratio (FIR) and new issue ratio (NIR) as measures of financial development developed by Goldsmith (1969), Singh (2008, p. 1616) claims that “the ratios show the activities of both primary and secondary financial markets…” However, by understanding that FIR measures the activities of both financial markets and intermediaries, while NIR just measures financial market activities, the author’simpression that FIR and NIR relates with primary and secondary markets cannot be supported. This is our first main contribution to the debate on the finance-growth nexus. The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the theoretical framework and the methodology developed is explained in Section 3. Next, the data and sample selection process are presented in Section 4, followed by discussions of the empirical results in Section 5. Section 6 concludes this paper. -6- 2. The Conceptual Framework and Methodology In examining the relationship between equity markets and growth, it is important to compare the role of equity markets and that of banks, or in a general term of the financial structure of an economy, because banks may have important roles on economic development that outweighs the role of the markets. In the case of developing countries or financially lessdeveloped countries, banking sectors are often more advanced compared to their equity market counterpart, especially in terms of their assets and long-term presence in the countries. Rioja and Valev (2004) and Lee (2012), for example, conjecture that the banking sectors is a more important determinant of economic development than equity markets in the early years of development. Therefore, if the role of the banking sector (or, equivalently, equity markets) is ignored, there may be a spurious positive relationship between equity markets (the banking sector) and economic development. However, the inclusion of the banking sector in the analysis of equity markets and economic growth in general still confirms the important role of equity markets as shown by Lee (2012), Antonios (2010), Rousseau and Wachtel (2000), Caporale, Howells and Soliman (2004), and Levine and Zervos (1996, 1998). We follow aBeck and Levine (2004b) and Rioja and Valev (2004) baseline dynamic panel growth regression to assess the relationship between an equity market and growth as follows: [1] 𝐺𝑟𝑜𝑤𝑡ℎ𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼1 𝐼𝑛𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑎𝑙 𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 −1 + 𝛽11 𝑃𝑟𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽12 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽13 𝐵𝑎𝑛𝑘𝑖𝑡 + 𝛾1′ 𝑋𝑡 + 𝜂1𝑖 + 𝜀1𝑖𝑡 where the subscript i and tdenote country and time period, respectively. Growth and Initial PGDP denotethe growth and initial value of real per capita GDP, respectively. Primary and Secondarydenote our variables of interest, i.e. the primary market measure and the secondary marketmeasure, respectively. X is a set of control variables consisting of average years of schooling and time dummies, is an unobservable country effect, and is the error termthat -7- is assumed to be homoscedastic and mutually uncorrelated over time and across countries either individually or collectively. Based on the public offering process and its corresponding functions as shown in Figure 1, we develop a conceptual framework for differentiating the primary market and the secondary market. The five functions summarized by Levine (2005)can practicallybe classified by type of market: the primary market adds to capital mobilization and allocation, while the secondary market plays other functions. INSERT FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE We develop the relationship between the two markets and economic growth by considering the existence of simultaneity between them. We treat our variables of interest and economic growth as endogenous variables and set them in an equilibrium mechanism. The explanation of this conceptual framework is based on the fact that the variables are determined simultaneously. For instance, an increasing trend in IPO volume and value are jointly determined by increasing economic growth (Draho 2004). Subrahmanyam and Titman (1999)argue that the interrelation between the primary market and the secondary market is essentially a “snow ball” effect. They postulate that the more new firms listing on a stock exchange, the more liquid and efficient the secondary market will be, and then the more able the market is to grow with more firms to list. In addition, we also argue that the primary market is also a supplier of the shares traded on the secondary market. Therefore, we use a simultaneous equation model to examine the interrelationship between the primary equity market, the secondary equity market, the banking sector and economic output, by adding three additional equations which has ceteris paribus interpretation as follows: [2] 𝑃𝑟𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼2 𝑃𝑟𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 −1 + 𝛽21 𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽22 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽23 𝐵𝑎𝑛𝑘𝑖𝑡 + 𝛾2′ 𝑋𝑡 + 𝜂2𝑖 + 𝜀2𝑖𝑡 [3] 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼3 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 −1 + 𝛽31 𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽32 𝑃𝑟𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽33 𝐵𝑎𝑛𝑘𝑖𝑡 + 𝛾3′ 𝑋𝑡 + 𝜂3𝑖 + 𝜀3𝑖𝑡 [4] 𝐵𝑎𝑛𝑘𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼4 𝐵𝑎𝑛𝑘𝑖𝑡 −1 + 𝛽41 𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽42 𝑃𝑟𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽43 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑦𝑖𝑡 + 𝛾4′ 𝑋𝑖𝑡 + 𝜂4𝑖 + 𝜀4𝑖𝑡 -8- Most of the abovementioned studies have been conducted by using 5, 8, or 10-year averagevalues. The main reason of the averaging is to accommodate business cycles and identify long-term relationship between the variables of interest (see for instance Harris & Tzavalis 1999, p. 427). However, Aretis and Demetriades (1997)argue that this approach imposes an average effect limitation making it impossible to capture each country’s individual idiosyncrasy. Attending to this, we argue that the use of annual time series data, instead of average data over a period of study, could possibly minimize the shortcoming of pure cross section regressions. This hasalso been tried by Beck and Levine (1999)who choose initial GDP as the only control variable. However, we accommodate here the two approaches: (1)estimate equation [1] by using the 5-year average data, and (2) estimate all four equations by using annual data. To estimate the unbiased and inconsistent growth regression parameters, we employ the two-steps system GMM developed by Arellano and Bond (1991), Arellano and Bover (1995), and Blundell and Bond (1998). The population moment orthogonality condition used for [1] is as follows: [5] E ∆𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃it −1 𝜀it = 0 for t=3,…,T The GMM estimators are claimed as suitable for small T and large N (Roodman 2006, 2009). While this does not create a problem for the average data, the implementation of the estimators to annual data is rather problematic. However, simulations conducted by Soto (2009) and Mitze (2012) show that the estimators could still be used in a finite sample. In fact, for a small sample (N=25, 35, or 50 and T=12, or 15), the level GMM estimators are relatively better than the system GMM estimators. Therefore, due to our small sample properties, for the annual data we avoid using the system GMM estimators used in Beck and Levine (2004b) and Rioja and Valev (2004).We also follow Roodman(2009) to employ the -9- collapsing technique and only use one lag to reduce the number of instruments used. The corresponding moment orthogonality condition used for [1] is therefore as follows:2 [6] E 𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃it −1 ∆𝜀it = 0 for t=3 We do not rule out the possibility of cross error correlationsbetween equations, therefore we estimate the equations separately. In addition, the separated estimation is beneficial because it might avoid the misspecification of the sensitivity of the individual equation that can occur with a joint estimation. The external exogenous explanatory variables we use here are those variables that are mainly found to be statistically significant to growth in existing studies such as in Levine and Zervos (1998), Rousseau and Wachtel (2000), Beck and Levine (1999), Rioja and Valev (2004), and Naceur and Ghazouani(1999).They aretrade openness (Trade), inflation rate (Inflation), government spending (Gov) and foreign direct investments (FDI). The main concern about estimating a simultaneous equation is the selection of exogenous variables that must be excluded in each equation to satisfy the order of condition for identification, i.e. the number of excluded exogenous variables in the equation is at least as large as the number of endogenous variables included in the same equation. This condition is important to make sure that there are the necessary numbers of potential instrument variables for the included endogenous variables for identification. The GMM models constructed in this article guarantee that this condition is satisfied. The choice of variables to include and exclude in the equations is also based on both theoretical and practical considerations. 3. Data The primary market series (Primary) that we use here is the dollar value of capital raised through equity public offerings (either through initial public offerings or seasonal equity offerings) and expressed as a percentage of GDP. We utilizedannual data of the total 2 The moment conditions for equation [2], [3], and [4] are set accordingly. - 10 - new capital raised by shares or investment flow over the period 1995-2011 that is publicly available on the World Exchange Federation’s(WFE) website.3In the case of a country that has more than one stock exchange listed as the member of WFE, we added up the observed values and treated the total as a representative primary market indicator for that country. The sample has 54 countries.4 Table 1 presents list of the countries and their corresponding data period coverage. INSERT TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE Market liquidity is used as a proxy for the secondary market series (Secondary). Here we used two measures of liquidity: the ratio of the value of shares traded to GDP (value traded) and the ratio of the value of shares traded to market capitalization. The latter is also known as the turnover ratio that measures not only market liquidity but also the transaction cost. These measures empirically have been used in many studies such as Levine and Zervos (1996, 1998), Rousseau and Wachtel (2000), Beck and Levine (2004a), Rioja and Valev (2004), and Yu, Hassan and Sanchez (2012). To measure the banking sector development (Bank), we experimented with two different indicators: private credit by deposit money bank and liquid liabilities. Both are as percentage of GDP and have been used in Levine and Zervos (1998) and Beck and Levine (2004a). Other bank development indicators such as total savings and bank assets, the private credit and the liquid liabilities consistently have a significant relationship with the growth indicator. Value traded, turnover ratio, private credit, and liquid liabilities data are collected from an updated September 2012 database on financial development and structure (Beck, Demirguc-Kunt & Levine 2000). As explained in Beck, Demirguc-Kunt and Levine (2001), turnover ratio, private credit, and liquid liabilitiesare calculated by deflating both the stock variable by the end-of-period customer price index and the flow variable by the average annual customer price index. This method is employed to make an adjustment for inflation. Similar adjustment is not needed for capital raised and 3 4 http://www.world-exchanges.org/ We excluded Taiwan due to its data unavailability in the World Bank’s database. - 11 - value traded because both are stock variables. Neither is needed for exogenous control variables. The data source is the World Development Indicators that is publicly available on the World Bank’s website. From the same source, GDP per capitais used as an indicator of economic development. All variables and their definitions are presented in Table 2. INSERT TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE In our estimation we transform the data by taking a natural logarithm of the value of variable (log(X)), except for Capital and Inflationwhere we taking a natural logarithm of the value of the variable plus one (log (1+X)). 4. Results 4.1. Descriptive statistics Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of our sample. The secondary market is more dominant than the primary market as shown by the value of total shares traded, either in terms of percentage of GDP or market capitalization. Over the sample period, the average of capital raised through the public equity offering markets is only 3 per cent of GDP, far below the percentage of shares traded on the stock exchanges with a value of 54 per cent of the national output. There are three cases where no firm in a country conducted theofferings in a particular year. This occurred in Germany and Switzerland in 2003 and in Mauritius in 2006. Hong Kong has been the only country which was able to raise new capital of more than a quarter of its GDP since 2003. In fact, it raised the highest record in 2010 with a value of 49 per cent. Hong Kong also has the highest total value traded in the last three years. In 2010, its value traded reached almost eight times the national product, which was much higher than the US that only reached four times its national product. The US equity market, however, is still the biggest market around the world in terms of market capitalization. Equity financing is also still not as important as bank credits. Banks provided about 38 times more capital than - 12 - the value of equity market. In terms of sources of financing, Domowitz, Glen and Madhavan (2001) show that on average over the period 1980-1997, in thirty countries equity financing is responsible only for 1.93 per cent of external financing. This may due to the pecking order paradigm of finance conjecturing firms that tend to use debt financing instead of equity financing (Froot, Scharfstein & Stein 1994).In terms of size, the secondary equity market does not relatively lag behind than the financial intermediaries. The average liquid liabilities or broad money (M3) is 85 per cent of GDP, which is 8 per cent higher than the average market capitalization (not shown in Table 3). INSERT TABLE 3 ABOUT HERE The relationship between economic development measured by GDP per capita and the primary market is illustrated in Figure 2. The scatter plot shows a positive correlation between the two variables for the year of 2010. The strength of the relationship is, however, rather weak, which is confirmed by the correlation coefficient between Capital raised and PGDP. A higher positive relationship between PGDP and other variables of the stock market and banks are visible. In general, however, simple correlation coefficients show there are positive associations between per capita GDP and all financial sector indicators. Economic output relatively has a positive high correlation to equity trading turnover and banking credit, while it has small, but still positive, correlation with capital raised through equity public offerings. INSERT FIGURE 2 ABOUT HERE 4.2. The 5-Year Average Data The estimates of the traditional growth model using 5-year average data for the full sample are presented in Table 4. There are three 5-year average periods: 1995-1999, 20002004, and 2005-2010. The last period consists of six years. Initial PGDPs are the value of - 13 - PGDP in year 1995, 2000 and 2005. We also deleted any samples that had only a one-year period. We experimented with two measurements of Capital: Initial Capital which is the average of two years of capital raised in the beginning of each period and AverageCapitalis just the 5-year average. With two alternative measurements for each Secondary and Banking, we therefore had eight (2x2x2) models of equation [1]. Their estimates are summarized in Table 4. INSERT TABLE 4 ABOUT HERE We find thatCapital, either measured by a 2- or 5-year average, is not statistically significant on Growth. Vtradedand Turnover on the other hand, are statistically significant, and confirmed the existing findings that liquidity of the secondary equity market is an important determinant of economic growth. 4.3. The Annual Data To explore the time dimension of our data, we also utilized our annual data. However due to our unbalanced data with variations in the length of time period, we decide to only use samples that had a minimum of 15 years data. This is important to accommodate panel timeseries methods. There were 28 countries that fulfilledthese requirements. Many studies have shown that many macroeconomic variables are often integrated. Here, we employ two panel unit root tests: the Im-Pesaran-Shin(IPS) test (Im, Pesaran & Shin 2003)and the CSD test(Pesaran, M. Hashem 2007). The two different tests actually have different results, depending on the inclusion of deterministic trends (see Table 5). However, the results in general reveal that all variables contain a unit root, except Turnover. The first test for non-stationarity (IPS W-t-bar) strongly confirms the existence of unit roots for PGDP, Credit and Liquid Liabilities, while the other variables are stationary. The second test (CADF Z-t-bar) creates a slightly different result depending on the choice of whether a trend is included. Only Turnoverand Capital consistently show that they are stationary and non- - 14 - stationary, respectively. In the case of inclusion of a trend, the statistics show thatPGDP, Capital and Vtraded contain unit roots. Despite these different empirical results, by also considering theoretical expectations, we finally decide to consider that all variables are nonstationary or integrated at order one, e.g. I(1).This has been confirmed by the results of the panel unit root tests for the first difference of the series. The results of the unit root tests bring us to transform all variables to their first difference. The transformed variables are therefore changes in the variables in focus. INSERT TABLE 5 ABOUT HERE INSERT TABLE 6 ABOUT HERE To avoid a spurious regression, we conducted a panel cointegration test of Pedroni and its results are presented in Table 6. We employ the tests with the inclusion of a deterministic intercept and trend, and one lag length due to our finite sample properties. It is safe to say that the test shows that in general there are no cointegration relationships between the economic development indicator and financial sector indicators. However, there is one exception to note;here might be a cointegration relationship between Capital and PGDP, Secondaryand Bank. Three of the six statistics indicate that those variables might be cointegrated. Formal econometric investigations to assess the relationship between growth and the financial sectors are conducted by one-step level GMM regressions using ARDL model specificationsand the results are presented in Table 7 and Table 8. Two specification tests are used to examine the appropriateness of the model and its assumptions used: a test for AR(2) in difference;Hansen (1982)test for joint validity of instruments and Pesaran, M. Hashem (2004)cross-sectional dependence test. All of them provide evidence that our model generally could be methodologically accepted. INSERT TABLE 7 ABOUT HERE - 15 - INSERT TABLE 8 ABOUT HERE Table 7 using Vtradedas the proxy for Secondary, in general, shows that the notion of supply-leading is confirmed; that the causality is from the secondary equity market to economic growth, in particular for the contemporaneous variables. Capital is not statistically significant on Growth, but it is statistically significant on Vtraded.This indicates that primary equity market development does not affect economic growth. It only affects the secondary equity market. The secondary market in fact also affects the primary markets. Meanwhile, the results show that there is bi-directional relationship between banking sectors and economic development. Table 8 shows the results when Turnover instead of Vtradedis used as the proxy for liquidity. The findings in Table 8are relatively similar to those found in Table 7. Turnover positively affects PGDP and Capital. However, both equity market indicators are not affected by PGDP. Capital is only statistically significant on Turnover when we use Liquid Liabilities as the proxy for Bank rather than Credit. 4.4. Further Analysis using the Annual Data As for robustness and sensitivity tests, we also experiment with a panel VAR as in Love and Zicchino (2006). In contrast with the models in [1]-[4] with contemporaneous independent variables and one lagged dependent variable, we here employ a first order panel VAR by only using one lag of all endogenous variables and present the estimation results in Table 9. INSERT TABLE 9 ABOUT HERE In the first part of Table 9, we find that Growth is not statistically affected by the lag value of Vtraded,instead the current value of Vtraded is affected by the lag value of PGDP. The current value of Vtraded is also affected by the lag value of Capital. The second part of Table - 16 - 9 shows that Turnover indeed affects Growth, but it has no statistical relationship with Capital. In general, the findings confirm that the primary market is not an important determinant of economic development;however, it does have an impact on the development of the secondary market. We also consider an alternative model in order to overcome the possibility of slope heterogeneity in the previous model specification. The slope heterogeneity is also important to accommodate the critique of Aretis and Demetriades (1997)on the individual country idiosyncrasy. Here we re-estimate our models by using the pooled mean group estimation (PMG) of Pesaran, M. Hashem, Shin and Smith (1999). This estimator allows for slope heterogeneity in the short run, but still assumes slope homogeneity in the long run. Even though the PMS estimator is robust to the existence of cointegration, Pesaran, M. Hashem, Shin and Smith (1999)still suggests conducting a test for a long-run relationship between variables before estimating. Table 6 indicates the possibility of a cointegration relationship between Capital, PGDP, Vtraded, and Credit. Based on this, we focus on the following model specification: [8] ∆𝐶𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑖𝑡 = 𝜃1𝑖 𝐶𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑖𝑡 −1 − 𝜎11𝑖 𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 − 𝜎12𝑖 𝑉𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡 − 𝜎13𝑖 𝐶𝑟𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼11 ∆𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼12 ∆𝑉𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼13 ∆𝐶𝑟𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑡 + 𝛿1𝑖 + 𝜀1𝑖𝑡 [9] ∆𝑉𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡 = 𝜃2𝑖 𝑉𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡 −1 − 𝜎21𝑖 𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 − 𝜎22𝑖 𝐶𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑖𝑡 − 𝜎23𝑖 𝐶𝑟𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼21 ∆𝑃𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼22 ∆𝐶𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑖𝑡 + 𝛼23 ∆𝐶𝑟𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑡 + 𝛿2𝑖 + 𝜀2𝑖𝑡 The estimates after time-demeaning (subtracting cross-sectional mean) to mitigate the impact of cross-sectional dependence are provided in Table 10. INSERT TABLE 10 ABOUT HERE All models indicate the possibility of a long-run relationship between Capital and Vtraded. In the long run, the causality relationship tends to go only from Capital to Vtraded. In the short run, however, the direction is reversed, i.e. it goes from Vtradedto Capital. These results support the majority of findings in the studies discussed in Section 1. - 17 - 4.5. Discussion All these results raise an important question on the importance of primary markets to economic development. If the primary markets only function as a supply for secondary markets (while in fact that the capital raised in the primary markets are more important to listed companies to do investment), we need to reconsider the capital accumulation channel to economic growth. Firstly, what is the main motivation of private firms going forpublic investment financing? Whatare the IPO proceeds used for? Private firms go public because they expect to get the following benefits and opportunities: future growth financing; improvements offinancial condition; incrementalmarket value and shareholder value; future external source of financing opportunities; merger and acquisition possibilities; stock exchange listing; increase in corporate image and reputation due to public awareness; and increase in founders’ wealth incremental (Draho 2004; Kleeburg 2005; Sherman 2005). However, a survey conducted by Brau and Fawcett (2006)shows that managers’ motives for going public is mainly for the purpose of future acquisitions. Investment financing as an alternative of debt, in fact, is the least motivation, behind the motives of market valuation, reputation, cost of capital, and ownership distribution. Secondly, is there disconnection between financial markets and the real sector? As indicated by Bencivenga, Smith and Starr (1996), speculative trading boosts investors’ reluctance to invest in a real rector investment project. Capitalists tend to invest their capital in financial markets, in particular the secondary markets. In this case, an increase in trading liquidity may lead to less long-term and productive investments because there will be less creation of new capital investments. Capital in equity markets is just transferred between investors through trading on stock exchanges. Savings are only utilizedfor capital formation and accumulation, but not for capital allocation to productive investments; therefore they may have no impact on the level of real activity. Singh, A (1997)also argues that the expected functions of trading and corporate controls from the secondary markets do not work efficiently. The primary markets - 18 - themselves are not a preferred way to undertake investment in firm-specific human capital. Thirdly, does financial liberalization exclude long-term commitment? The main assumption of Bencivenga, Smith and Starr (1996) model is that a more productive investment needs a longterm fund commitment through the creation of new capital. Financial liberalisation allows foreign investors to invest in a country, allowing them to withdraw their money at any time without restrictions. They may prefer to just buy and sell existing shares on stock exchanges. The functions of trading and corporate controlcannot work if there is no long-term commitment from investors, as indicated by Bhide (1993) that liquidity makes investors reluctant to monitor managers. 5. Conclusion This paper examines the different role played by primary and secondary equity markets in relation to economic growth. While most studies on thefinance-growth nexus only consider secondary market indicators and tend to underestimate the primary market counterpart when examining the relationship between stock market development and economic growth, this study separates and integrates both markets at the same time by using a simultaneous framework.From a microeconomic perspective, listed firms could raise money through primary markets by offering equity to publics, with no additional cash inflow for firms when their stocks traded on a stock exchange(s). Furthermore, the transactions on the exchanges are not classified as an investment from macroeconomic point of view, while selling new shares is. We investigate capital accumulation function of equity markets here by employing the dynamicpanel regressions of Blundell and Bond (1998) and other alternative model specifications for small sample of 54 countries over the period 1995-2010. We show that capital raised through primary equity markets are not an important determinant of economic growth. The primary markets are only significant as a supplier of new shares to secondary - 19 - market activities on the stock exchanges. We also confirm the existing findings on the importance of secondary market activities on the stock exchange and that trading liquidity is an important determinant of the economic growth. - 20 - References Ang, JB 2008, 'A Survey of Recent Developments in the Literature of Finance and Growth', Journal of Economic Surveys, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 536-76. Antonios, A 2010, 'Financial Development and Economic Growth: A Comparative Study between 15 European Union Member States ', International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, vol. 2010, no. 35, pp. 143-9. Arellano, M & Bond, S 1991, 'Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application toEmployment Equations', The Review of Economic Studies, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 277-97. Arellano, M & Bover, O 1995, 'Another Look at the Instrumental Variables Estimation of Error-components Models', Journal of Econometrics, vol. 68, pp. 29-51. Aretis, P & Demetriades, P 1997, 'Financial Development and Economic Growth: Assessing the Evidence', The Economic Journal, vol. 107, no. 442, pp. 783-99. Atje, R & Jovanovic, B 1993, 'Stock Markets and Development', European Economic Review, vol. 37, pp. 632-40. Beck, T, Demirguc-Kunt, A & Levine, R 2000, 'A New Database on Financial Development and Structure ', World Bank Economic Review, vol. 14, pp. 597-605. —— 2001, 'The Financial Structure Database', in A Demirguc-Kunt & R Levine (eds), Financial Structure and Economic Growth: A Cross-country Comparison of Banks, Markets, and Development, MIT Press, Massachusetts, pp. 17-80. Beck, T & Levine, R 2004a, 'Stock Markets, Banks, and Growth: Panel Evidence', Journal of Banking and Finance, vol. 28, pp. 423-42. —— 2004b, 'Stock Markets, Banks, and Growth: Panel Evidence', Journal of Banking & Finance, vol. 28, pp. 423-42. Bencivenga, VR, Smith, BD & Starr, RM 1996, 'Equity Markets, Transactions Costs and Capital Accumulation: An Illustration', The World Bank Economic Review, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 241-65. Bhide, A 1993, 'The Hidden Costs of Stock Market Liquidity', Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 31-51. Blackburne, EF & Frank, MW 2007, 'Estimation of Nonstationary Heterogeneous Panels', The Stata Journal, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 197-208. Blundell, R & Bond, S 1998, 'Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models', Journal of Econometrics, vol. 87, pp. 115-43. Brau, JC & Fawcett, SE 2006, 'Intitial Public Offerings: An Analysis of Theory and Practise', The Journal of Finance, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 399-436. Caporale, GM, Howells, PGA & Soliman, AM 2004, 'Stock Market Development and Economic Growth: The Causal Linkage', Journal of Economic Development, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 33-50. - 21 - Chakraborty, I 2010, 'Financial Development and Economic Growth in India: An Analysis of the Post-reform Period', South Asia Economic Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 287-308. Chaudhuri, K & Smiles, S 2004, 'Stock Market and Aggregate Economic Activity: Evidence from Australia', Applied Financial Economics, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 121-9. Deidda, L & Fattouh, B 2002, 'Non-linearity between Finance and Growth', Economic Letters, vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 339-45. Demirguc-Kunt, A & Levine, R 1996a, 'Stock Market Development and Financial Intermediaries: Stylized Facts', The World Bank Economic Review, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 291-321. —— 1996b, 'Stock Markets, Corporate Finance, and Economic Growth: An Overview', The World Bank Economic Review, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 223-39. Domowitz, I, Glen, J & Madhavan, A 2001, 'International Evidence on Aggregate Corporate Financing Decisions', in A Demirguc-Kunt & R Levine (eds), Financial Structure and Economic Growth: A Cross-country Comparison of Banks, Markets, and Development, MIT Press, Massachusetts, pp. 263-95. Draho, J 2004, The IPO Decision: Why and How Companies Go Public, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham UK. Froot, KA, Scharfstein, DS & Stein, JC 1994, 'A Framework for Risk Management', Harvard Business Review, vol. November-December, pp. 91-102. Fry, MJ 1997, 'In Favour of Financial Liberalisation', The Economic Journal, vol. 107, no. 442, pp. 754-70. Gan, C, Lee, M, Yong, HHA & Zhang, J 2006, 'Macroeconomic Variables and Stock Market Interactions: New Zealand Evidence', Investment Management and Financial Innovations, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 89-101. Goldsmith, RW 1969, Financial Structure and Development, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut. Greenwood, J & Jovanovic, B 1990, 'Financial Development, Growth, and the Distribution of Income', Journal of Political Economy, vol. 98, no. 5, pp. 1076-107. Halkos, GE & Trigoni, MK 2010, 'Financial Development and Economic Growth: Evidence from the European Union', Managerial Finance, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 949-57. Hansen, LP 1982, 'Large Sample Properties of Generalized Method of Moments Estimators', Econometrica, vol. 50, pp. 1029-54. Harris, RDF 1997, 'Stock Markets and Development: A Re-assessment', European Economic Review, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 139-46. Harris, RDF & Tzavalis, E 1999, 'Inference for Unit Roots in Dynamic Panels Where the Time Dimension is Fixed', Journal of Econometrics, vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 201-26. Im, KS, Pesaran, MH & Shin, Y 2003, 'Testingfor Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels', Journal of Econometrics, vol. 115, pp. 53-74. - 22 - Kao, C 1999, 'Spurious Regression and Residual-based Tests for Cointegration in Panel Data', Journal of Econometrics, vol. 90, pp. 1-44. Kaplan, M 2008, 'The Impact of Stock Market on Real Economic Activity: Evidence from Turkey', Journal of Applied Science, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 374-8. Kleeburg, RP 2005, Intitial Public Offerings, Thomson, Ohio. Lee, B-S 2012, 'Bank-based and Market-based Financial Systems: Time-series Evidence', Pasific-Basin Finance Journal, vol. 20, pp. 173-97. Levine, R 2005, 'Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence', in P Aghion & SN Durlauf (eds), Handbook of Economic Growth, Elsevier B.V., North Holland, Burlington, vol. 1A, pp. 865-934. Levine, R & Zervos, S 1996, 'Stock Market Development and Financial Intermediaries: Stylized Facts', The World Bank Economic Review, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 323-39. —— 1998, 'Stock Markets, Banks, and Economic Growth', The American Economic Review, vol. 88, no. 3, pp. 537-58. Love, I & Zicchino, L 2006, 'Financial Development and Dynamic Investment Behavoir: Evidence from Panel VAR', The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, vol. 46, pp. 190210. Mankiw, NG 2010, Macroeconomics, 7th International edn, Worth Palgrave Macmillan, New York. Maysami, RC, Howe, LC & Hamzah, MA 2004, 'Relationship between Macroeconomic Variables and Stock Market Indices: Cointegration Evidence from Stock Exchange of Singapore’s All-S Sector Indices', Jurnal Pengurusan, vol. 24, pp. 47-77. Mitze, T 2012, 'Dynamic Simultanoeus Equations with Panel Data: Small Sample Properties and Application to Regional Economeric Modelling ', in Empirical Modelling in Regional Science. Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems 657, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Hidenberg, pp. 219-71. Nagaishi, M 1999, 'Stock Market Development and Economic Growth: Dubious Relationship', Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 34, no. 29, pp. 2004-12. Patrick, HT 1966, 'Financial Development and Economic Growth in Underdeveloped Countries', Economic Development and Cultural Change, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 174-89. Pesaran, MH 2004, General Diagnostic Tests for Cross Section Dependence in Panels, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). Pesaran, MH 2007, 'A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross-sectional Dependence', Journal of Applied Econometrics, vol. 22, pp. 265-312. Pesaran, MH, Shin, Y & Smith, RP 1999, 'Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels', Journal of the American Statistical Association, vol. 94, no. 446, pp. 621-34. - 23 - Pilbeam, K 2010, Finance and Financial Markets, 3rd edn, Palgrave Macmillan, New York. Rachdi, H & Mbarek, HB 2011, 'The Causality between Financial Development and Economic Growth: Panel Data Cointegration and GMM System Approaches', Intemational Joumal of Eeonomics and Finance, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 143-51. Rioja, F & Valev, N 2004, 'Does One Size Fit All? A Reexamination of the Finance and Growth Relationship', Journal of Development Economics, vol. 74, pp. 429-47. Roodman, D 2006, How to Do xtabond2: An Introduction to "Difference" and "System" GMM in STATA, Center for Global Development. —— 2009, 'Practitioner's Corner: A Note on the Theme of Too Many Instruments', Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 135-58. Rousseau, PL & Wachtel, P 2000, 'Equity Markets and Growth: Cross-country Evidence on Timing and Outcomes 1980-1995', Journal of Banking and Finance, vol. 24, pp. 1933-57. Shahbaz, M, Ahmed, N & Ali, L 2008, 'Stock Market Development and Economic Growth: Ardl Causality in Pakistan', International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, vol. March, no. 14, pp. 182-95. Sherman, AJ 2005, Raising Capital, 2nd edn, American Management Association, New York. Siliverstovs, B & Duong, MH 2006, On the Role of Stock Market for Real Economic Activity: Evidence for Europe, German Institute of Economic Research Discussion Papers 5999, Berlin. Singh, A 1997, 'Financial Liberalisation, Stockmarkets and Economic Development', The Economic Journal, vol. 107, no. 442, pp. 771-82. Singh, T 2008, 'Financial Development and Economic Growth Nexus: a Time-series Evidence from India', Applied Economics, no. 40, pp. 1615-27. Soto, M 2009, System GMM Estimation with a Small Sample Unitat de Fonaments de l'Anàlisi Econòmica (UAB) and Institut d'Anàlisi Econòmica (CSIC). Subrahmanyam, A & Titman, S 1999, 'The Going-Public Decision and the Development of Financial Markets', The Journal of Finance, vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 1045-82. Yu, J-S, Hassan, MK & Sanchez, B 2012, 'A Re-examination of Financial Development, Stock Market Developments and Economic Growth', Applied Economics, vol. 44, no. 27, pp. 3479-89. - 24 - Figure 1.Public equity offering process and the functions of the equity markets 9.00 CHE 8.00 IND Capital raised to GDP (%) 7.00 6.00 BRA 5.00 MYS 4.00 IRL SGPCAN ESP GBR POL 3.00 NOR CHN PHL 2.00 EGY IDN MAR CYP GRC ISR CHL THA JOR LKA 1.00 MEX PER ZAF MUS COL TUR RUS HUN SAU ARG KOR MLT SVN USA JPN AUT DEU 0.00 3.00 3.50 4.00 4.50 Per capita GDP (in log) 5.00 5.50 Figure 2.Scatter plot capital raised (as percentage of GDP) and GDP per capital (current USD, in log), 2010 Note: Hong Kong is excluded because it is an outlier. Its ratio of capital raised to GDP is 48.76%. Australia and Iran are not displayed due to incomplete data. Table 1 List of selected countries, their corresponding exchanges and data period coverage Country Stock exchange Data period Argentina Buenos Aires SE 1995-2010 Australia Australian SE 1995-2010 Austria Wiener Börse 1995-2010 Belgium Euronext Brussels 1995-1999 Bermuda1 Bermuda SE 1998-2006 Brazil BM&FBOVESPA 1995-2010 Canada2 TMX Group 1995-2010 Chile Santiago SE 1995-2010 China3 Combined 2001-2010 Colombia Colombia SE 2003-2010 Cyprus Cyprus SE 2004-2010 Denmark4 Copenhagen SE 1995-2003 Egypt Egyptian Exchange 2004-2010 Finland4 OMX Helsinki SE 1995-2003 France Euronext Paris 1995-1999 Germany Deutsche Börse 1995-2010 Greece Athens Exchange 1995-2010 Hong Kong Hong Kong Exchanges 1995-2010 Hungary Budapest SE 2000-2010 India5 Combined 2001-2010 Indonesia Indonesia SE 1995-2010 Iran Tehran SE 1995-2010 Ireland Irish SE 1995-2010 Israel Tel Aviv SE 1995-2010 Italy BorsaItaliana 1995-2008 Japan6 Combined 1995-2010 Jordan Amman SE 2006-2010 South Korea Korea Exchange 1995-2010 Luxembourg Luxembourg SE 1995-2006 Malaysia Bursa Malaysia 1995-2010 Malta Malta SE 1998-2010 Mauritius Mauritius SE 2006-2010 Mexico7 Mexican Exchange 1995-2010 Morocco Casablanca SE 2009-2010 Netherland Euronext Amsterdam 1995-1999 New Zealand New Zealand SE 1995-2008 Norway Oslo Børs 1995-2010 Peru Lima SE 1995-2010 Philippines Philippine SE 1995-2010 Poland Warsaw SE 1995-2010 Portugal Lisbon SE 1995-2000 Russia8 Combined 2009-2010 Saudi Saudi Stock Market - Tadawul 2008-2010 Singapore Singapore SE 1999-2010 Slovenia Ljubljana SE 1996-2010 South Africa Johannesburg SE 1995-2010 Spain BME Spanish Exchanges 1998-2010 Sri Lanka Colombo SE 1997-2010 Sweden4 OMX Stockholm SE 1995-2003 Switzerland9 SIX Swiss Exchange 1995-2010 Taiwan10 Combined 1995-2010 Thailand Thailand SE 1995-2010 Turkey Istanbul SE 1995-2010 U.K. London SE Group 1995-2010 U.S.A11 Combined 1995-2010 Note:(1) 1999-2000 is not available. (2) Before 2001, combined Canadian Venture Exchange and Toronto Stock Exchange. 2008 data is not available. (3) Combined Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange. (4) Merged into NASDAQ OMX Nordic Exchange in 2004. After that data for each country is not available. (5) Combined Bombay Stock Exchange and National Stock Exchange India. 2011 data is only from National Stock Exchange India. (6) Combined Tokyo Stock Exchange Group and Osaka Securities Exchange. Before 2009, JASDAQ also included. (7) 2001 data is not available. (8) Since 2010, combined MICEX and RTS Stock Exchange. (9) 2008 data is not available. (10) Taiwan is excluded. Since 2010, combined Taiwan Stock Exchange Corp and Gretai Securities Market. Before that, data is only from Taiwan Stock Exchange Corp. (11) Combined NASDAQ and NYSE. Before 2005, combined NASDAQ, NYSE and American Stock Exchange. Table 2 List of variables and their definitions Variable Definition Source PGDP WDI Capital raised Value traded Turnover Private credit Liquid liabilities Schooling FDI Trade Gov Inflation Gross domestic product divided by the number of population (in current USD) Total amount of capital raised through primary equity markets either by an initial public offering or seasonal equity offering (as a percentage of GDP) Value of total shares traded on the stock market exchange (as a percentage of GDP) Deflated value of total shares traded on the stock market exchange (as a percentage of market capitalization) Deflated private credit by deposit money banks (as percentage of GDP) Deflated liquid liabilities (as percentage of GDP) Gross rate of secondary enrollment (as percentage of GDP) Net inflow of foreign direct investment (as percentage of GDP) Total value of export and import of goods and services (as percentage of GDP) Government expense (as percentage of GDP) Annual percentage change in the consumer price index WFE and WDI (for GDP) Beck, Demirguc-Kunt and Levine(2000) Beck, Demirguc-Kunt and Levine(2000) Beck, Demirguc-Kunt and Levine(2000) Beck, Demirguc-Kunt and Levine(2000) WDI WDI WDI WDI WDI The deflation formula for calculating turnover is 𝑉𝑡 𝐶𝑃𝐼𝑡 𝑀 𝑀 0.5 × ( 𝑡 𝐶𝑃𝐼 + 𝑡−1 𝐶𝑃𝐼 ) 𝑡 𝑡−1 The deflation formula for calculating private credit is 𝐶 𝐶 0.5 × ( 𝑡 𝐶𝑃𝐼 + 𝑡−1 𝐶𝑃𝐼 ) 𝑡 𝑡−1 𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑡 𝐶𝑃𝐼𝑡 The deflation formula for calculating liquid liabilities is 𝐿𝐿 𝐿𝐿 0.5 × ( 𝑡 𝐶𝑃𝐼 + 𝑡−1 𝐶𝑃𝐼 ) 𝑡 𝑡−1 𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑡 𝐶𝑃𝐼𝑡 Where Vt Mt Ct LLt CPIt 𝐶𝑃𝐼 t GDPt : the value of total shares traded on the stock market exchange at year t : the value of total stock market capitalization of the stock market exchange at year t : the value of private credit by deposit money banks at year t : the value of liquid liabilities at year t : End-of-period customer price index at year t : Average annual customer price index at year t :the value of GDP at year t -1- Table 3 Descriptive statistics Statistic PGDP Capital Vtraded Turnover Credit Liquid liabilities 664 19,335.596 17,154.697 459.230 93,366.810 660 2.482 4.636 0.000 48.763 655 53.904 75.364 0.271 740.057 655 64.007 58.0187 0.360 435.561 626 76.600 47.828 9.617 270.840 612 85.431 58.620 17.319 361.885 Correlation (No. observations = 604) PGDP 1.000 Capital 0.162 Vtraded 0.385 Turnover 0.298 Credit 0.587 Liquid liabilities 0.529 1.000 0.512 0.073 0.280 0.486 1.000 0.639 0.402 0.408 1.000 0.233 0.129 1.000 0.733 1.000 Pesaran CD Cross-sectional Independence test Average coefficient 0.775 0.100 CD-statistic 57.76*** 7.46*** 0.329 24.57*** 0.370 27.62*** 0.148 10.46*** 0.327 23.51*** Full Sample No. observations Mean Std. dev Min Max Table 4 Two-step system GMM estimates regressions of the relationship between the primary market, the secondary market (Vtradedor Turnover), banks (Credit or Liquid Liabilities) and growth, 5-year average data Variables Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 Model 8 Initial PGDP Schooling Initial Capital -0.0161 (0.0118) 0.0373 (0.0450) 0.0150 (0.0308) -0.0254* (0.0129) 0.0956 (0.0594) -0.0388 (0.0519) -0.0208** (0.0102) 0.0720* (0.0367) -0.0026 (0.0364) -0.0286** (0.0138) 0.1251** (0.0584) -0.0530 (0.0497) Average Capital Vtraded -0.0095 (0.0068) -0.0107*** (0.0024) Turnover Credit Liquid Liabilities -0.0115** (0.0054) -0.0002 (0.0178) 0.0044 (0.0194) 0.0219 (0.0176) -0.0159 (0.0120) 0.0415 (0.0415) -0.0262* (0.0144) 0.0968* (0.0576) -0.0204* (0.0106) 0.0752** (0.0291) -0.0290* (0.0144) 0.1262** (0.0511) 0.0113 (0.0273) -0.0094 (0.0070) -0.0399 (0.0505) -0.0104*** (0.0030) -0.0058 (0.0308) -0.0544 (0.0446) -0.0114** (0.0055) -0.0010 (0.0178) -0.0113*** (0.0024) -0.0115*** (0.0026) 0.0036 (0.0188) 0.0151 (0.0185) 0.0236 (0.0203) 0.0162 (0.0203) Observations 112 110 112 110 112 110 112 110 Number of instruments 22 22 22 22 22 22 22 22 AR(1) 0.267 0.234 0.256 0.235 0.263 0.234 0.253 0.234 Hansen test 0.146 0.220 0.146 0.273 0.152 0.219 0.151 0.291 Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. The standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation with Windmeijer correction. Covariance matrix estimate is based on small sample correction. The number of instruments used is reduced both by using only one lag (i.e. lag 1) and collapsing the instrument matrix. The instrument variable set is one-period lag exogenous variables. Year dummies are included. ***, **, and * indicate p<0.01, p<0.05, and p<0.1, respectively. Table 5 Panel unit root tests Variable In Level PGDP Capital Vtraded Turnover Credit Liquid liabilities IPS Test [W-t-bar] No trend -0.738 -2.456*** -4.045*** -3.792*** 0.999 1.637 trend 0.637 -3.125*** -1.360* -1.626* -0.677 0.645 CADF Test [Z-t-bar] No trend -2.026** 2.354 -1.950* -3.499*** 4.024 -0.091 trend -1.165 -0.257 0.013 -3.414*** -1.470* -3.065*** In First Difference PGDP -5.813*** -5.188*** -3.605*** -1.159 Capital -11.116*** -7.443*** -7.376*** -5.846*** Vtraded -6.766*** -6.939*** -3.852*** -6.568*** Turnover -8.261*** -6.523*** -5.925*** -4.863*** Credit -5.439*** -4.153*** -3.908*** -2.661*** Liquid liabilities -4.454*** -2.823*** -3.225*** -2.594*** Notes: The statistics are computed in all the unit root tests by making cross-sectional removal. Null hypothesis is panels contain unit roots. We set the number of lag for ADF regression in the tests to one due to our limited sample size. All calculations are using Stata’s routine xtunitrootandpescadfdeveloped by Lewansowski.***, ** and * indicate significance at 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively. -1- Table 6 Pedroni residual panel cointegration tests Statistics PGDP Dependent variable Capital Turnover Liquid liabilities Within-dimension Panel v-Statistics Panel rho-Statistic Panel PP-Statistic Panel ADF-Statistic -0.3095 5.1407 3.6578 3.8165 -4.0629 3.1375 -15.3214*** -6.7970*** -0.0695 2.8094 -2.5992*** 0.4843 0.3148 5.9795 6.3946 3.0789 Between-dimension Group rho-Statistic Group PP-Statistic Group ADF-Statistic 6.7750 3.0757 1.4087 3.4879 -20.6458*** -2.3154** 5.4367 -3.1871*** -0.1628 6.7514 2.6298 1.2453 PGDP Capital Turnover Credit Within-dimension Panel v-Statistics Panel rho-Statistic Panel PP-Statistic Panel ADF-Statistic 0.5547 4.2111 0.7440 1.9496 -3.0941 3.3241 16.3283*** -6.2837*** 0.7530 3.3727 -3.3996*** -0.8694 1.2756 4.2328 1.2856 1.8964 Between-dimension Group rho-Statistic Group PP-Statistic Group ADF-Statistic 6.5306 3.0942 3.8731 3.5539 -20.0094*** -3.1546*** 5.4137 -3.8543*** -0.0667 6.4128 2.9675 2.6784 PGDP Capital Vtraded Credit Within-dimension Panel v-Statistics Panel rho-Statistic Panel PP-Statistic Panel ADF-Statistic -0.8486 5.4232 3.7271 2.9966 -4.1360 2.1834 -29.0333*** -10.4401*** 0.3010 4.3589 1.3954 -1.7631*** 0.2929 4.7979 2.3868 1.4703 Between-dimension Group rho-Statistic Group PP-Statistic Group ADF-Statistic 6.9818 4.2852 3.7312 3.3216 -28.1544*** -3.4975*** 6.8511 2.7530 -3.4995*** 6.2594 1.4635 -0.6597 PGDP Capital Vtraded Liquid liabilities Within-dimension Panel v-Statistics Panel rho-Statistic Panel PP-Statistic Panel ADF-Statistic -0.2637 5.5224 4.7159 3.2335 -4.5704 2.1365 -24.6427*** -10.6660*** 0.2883 4.5885 2.3315 0.9370 0.5717 5.9360 6.3645 3.4997 Between-dimension Group rho-Statistic Group PP-Statistic Group ADF-Statistic 6.8536 3.3992 0.3264 3.4475 -25.1713*** -2.3615*** 7.2366 3.4434 -1.8763*** 6.5868 1.6325 0.8027 Notes: The statistics are computed by using the assumptions of deterministic trend and trend, degree of freedom corrected Dickey-Fuller residual variances, one lag length and Newey-West automatic bandwith selection and Bartlett kernel. All calculations are using Eviews.***, ** and * indicate significance at 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively Table 7 One-step level GMM estimates regressions of the relationship between the primary market, the secondary market (VTraded), banks (Credit or Liquid Liabilities) and growth, selective sample, annual data Variables PGDP Capital Vtraded Credit PGDP Capital Vtraded Liquid liabilities PGDPt-1 0.8494*** 0.0371 -0.3587 0.2327*** 0.3825** 0.0030 0.1644 0.1337** (0.1449) (0.0393) (0.4342) (0.0538) (0.1442) (0.0167) (0.3436) (0.0637) Capitalt-1 -0.6810 -0.3659 6.1435 -0.6322 1.3451 -0.3063 5.9331** -0.7379 (2.1880) (0.3885) (3.9578) (0.9528) (1.5183) (0.4173) (2.7759) (0.7273) Vtradedt-1 0.0159 0.0029 0.3154* 0.0518 -0.1073 -0.0064 0.4417*** 0.0684*** (0.0923) (0.0174) (0.1763) (0.0343) (0.0653) (0.0098) (0.1493) (0.0223) Creditt-1 1.0379** 0.2038* -1.6515* 0.5568*** (0.4875) (0.1109) (0.8203) (0.1253) Liquid liabilitiest-1 0.2234 0.1368** -0.5268 0.5481*** (0.3448) (0.0643) (0.8166) (0.1115) PGDPt -0.0391 0.7703** -0.1479*** -0.0102 0.5442** -0.0134 (0.0241) (0.2934) (0.0426) (0.0112) (0.2225) (0.0657) Capitalt -2.9643 6.2154* -1.2713 -0.8460 2.8149 -0.7194 (2.1230) (3.5323) (0.9195) (0.7433) (2.2745) (0.7198) Vtradedt 0.3319*** 0.0354** 0.0524 0.3281*** 0.0205** -0.0327 (0.1096) (0.0154) (0.0542) (0.0915) (0.0099) (0.0393) Creditt -2.1315*** -0.2419 1.7536 (0.6559) (0.1480) (1.2111) Liquid liabilitiest -0.1355 -0.0878 -0.5475 (0.4027) (0.0550) (0.9121) Observations 214 214 232 214 212 212 232 212 Number of instruments 26 26 26 26 26 26 26 26 AR(2) 0.847 0.183 0.0720 0.325 0.896 0.148 0.0287 0.273 Hansen test 0.134 0.788 0.236 0.301 0.269 0.691 0.233 0.415 Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. The standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation with Windmeijer correction. Covariance matrix estimate is based on small sample correction. The number of instruments used is reduced both by using only one lag (i.e. lag 1) and collapsing the instrument matrix. The instrument variable set is one-period lag external exogenous variables. ***, **, and * indicate p<0.01, p<0.05, and p<0.1, respectively. -1- Table 8 One-step level GMM estimates regressions of the relationship between the primary market, the secondary market (Turnover), banks (Credit or Liquid Liabilities) and growth, selective sample, annual data Variables PGDP Capital Turnover Credit PGDP Capital Turnover Liquid liabilities PGDPt-1 0.8184*** 0.0242 0.1597 0.2588*** 0.3843*** 0.0071 0.0335 0.1097* (0.1693) (0.0509) (0.5092) (0.0685) (0.1023) (0.0224) (0.4746) (0.0639) Capitalt-1 0.6567 -0.0329 -4.9634 -0.8915 3.3917 0.1490 -6.6674 -1.9437* (1.6326) (0.2815) (4.4413) (0.7660) (2.1209) (0.4587) (5.3178) (1.0106) Turnovert-1 0.2481 -0.0059 0.4945* 0.1277** 0.0522 -0.0289* 0.5701** 0.1572** (0.1821) (0.0198) (0.2467) (0.0511) (0.1408) (0.0141) (0.2225) (0.0632) Creditt-1 0.7336 0.1382 0.0769 0.4940*** (0.4662) (0.1110) (1.2944) (0.1410) Liquid liabilitiest-1 0.0370 0.0813 0.2752 0.4527*** (0.2795) (0.0764) (1.0662) (0.1243) PGDPt -0.0318 0.5138 -0.1451** -0.0174 0.5585 -0.0397 (0.0374) (0.4575) (0.0675) (0.0244) (0.4527) (0.0824) Capitalt -1.9387 5.4022 -0.6430 -1.5140 5.6965* -0.1909 (1.3434) (3.2198) (0.5688) (0.9548) (2.9555) (0.5925) Turnovert 0.2013* 0.0347** -0.0199 0.3126*** 0.0366** -0.0413 (0.1057) (0.0141) (0.0467) (0.0966) (0.0156) (0.0542) Creditt -1.9773** -0.1436 -0.6942 (0.8463) (0.1700) (1.7830) Liquid liabilitiest -0.4645 -0.0256 -0.8631 (0.4141) (0.0925) (1.3182) Observations 212 212 212 214 214 214 214 212 Number of instruments 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 AR(2) 0.734 0.560 0.889 0.286 0.982 0.642 0.939 0.132 Hansen test 0.398 0.624 0.735 0.821 0.395 0.655 0.536 0.783 Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. The standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation with Windmeijer correction. Covariance matrix estimate is based on small sample correction. The number of instruments used is reduced both by using only one lag (i.e. lag 1) and collapsing the instrument matrix. The instrument variable set is one-period lag external exogenous variables. ***, **, and * indicate p<0.01, p<0.05, and p<0.1, respectively. -2- Table 9 Panel 4-variable VAR estimates Response to PGDPt-1 Capitalt-1 Vtradedt-1 Creditt-1/Liquid liabilitiest-1 PGDP Capital Vtraded 0.9918*** (0.0396) -0.0440 (0.1853) 0.0214 (0.0153) -0.0826 (0.0637) -0.0106 (0.0082) 0.1856 (0.2539) 0.0044 (0.0037) 0.0111 (0.0087) 0.1587** (0.0761) 1.6927** (0.6929) 0.8476*** (0.0320) -0.2693*** (0.0.990) No. Observations Capitalt-1 Turnovert-1 Creditt-1/Liquid liabilitiest-1 0.0977*** (0.0294) -0.0569 (0.2522) 0.0404*** (0.0104) 0.8196*** (0.3778) 0.9727*** (0.0374) 0.0077 (0.1817) 0.0187 (0.0167) 0.0012 (0.0553) 354 Capital Vtraded Liquid liabilities -0.0095 (0.0075) 0.1615 (0.2564) 0.0043 (0.0034) 0.0179 (0.0144) 0.1205 (0.0752) 2.0685** (0.7530) 0.8494*** (0.0318) -0.3742*** (0.1220) 0.0163 (0.0186) 0.2085* (0.1153) 0.0259*** (0.0077) 0.8294*** (0.0314) Capital Turnover Liquid liabilities -0.0064 (0.0067) 0.1665 (0.2541) 0.0013 (0.0027) 0.0224 (0.0157) 0.0984 (0.1002) -0.9499 (0.8474) 0.7582*** (0.0494) -0.1184 (0.1452) 0.0268 (0.0178) 0.2340** (0.1176) 0.0156* (0.0088) 0.8512*** (0.0308) 351 Response to PGDPt-1 Response of Credit PGDP PGDP Capital Turnover 0.9714*** (0.0434) -0.0414 (0.1887) 0.0379* (0.0229) -0.0654 (0.0607) -0.0092 (0.0082) 0.1967 (0.2483) 0.0025 (0.0029) 0.0138 (0.0093) 0.1335 (0.0945) -1.214 (0.7996) 0.7458*** (0.0471) -0.1153 (0.1076) Response of Credit PGDP 0.1147*** (0.0262) 0.0519 (0.2437) 0.0194 (0.0132) 0.8445*** (0.0352) 0.9464*** (0.0416) 0.0073 (0.1859) 0.0439* (0.0249) -0.0034 (0.0562) No.Observations 354 352 Notes: Time-demeaned removal and helmet transformation are employed before the system GMM estimation. Statapropertiaryroutine pvar by Love and Zicchino (2006).***, ** and * indicate significance at 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively. Table 10 Estimates of heterogeneous panels Variables CAPITAL Long-run relationship PGDP -0.0020** (0.0009) Vtrade 0.0001 (0.0004) Credit -0.0002 (0.0007) Speed of adjustment Short-run relationship PGDP -0.8780*** (0.0833) VTRADED Long -un relationship PGDP Capital Credit Speed of adjustment 4.9401*** (0.8080) 1.0873*** (0.0841) -0.0309 (0.1401) -0.3026*** (0.0497) Short-run relationship 0.0174 PGDP 0.2412 (0.0294) (0.1852) Vtraded 0.0094* Capital 2.9015 (0.0052) (2.3985) Credit -0.0226 Credit 1.0976*** (0.0232) (0.2892) Notes: Estimates and standard errors (in parentheses) are calculated by using Stata’s routine xtpmg developed by Blackburne and Frank (2007). ***, ** and * indicate significance at 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.