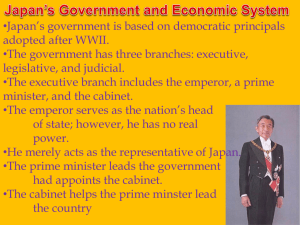

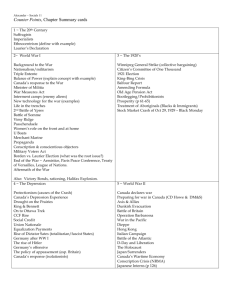

President-Prime Minister Relations, Party Systems

advertisement