Looking at the Movies CH 1 - Welcome

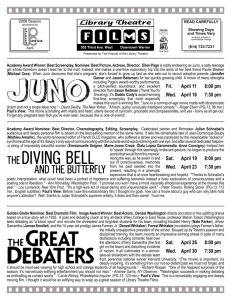

advertisement

Ways of Looking at Movies Every movie is a complex synthesis—a combination of many separate, interrelated elements that form a coherent whole. A quick scan of this book’s table of contents will give you an idea of just how many elements get mixed together to make a movie. Anyone attempting to comprehend a complex synthesis must rely on analysis—the act of taking something complicated apart to figure out what it is made of and how it all fits together. The expressive agility of movies Even the best seats in the house offer a viewer of a theatrical production like Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street only one unchanging view of the action. The stage provides the audience a single wide-angle view of the scene in which the title character is reintroduced to the set of razors he will use in his bloody quest for revenge [1]. In contrast, cinema’s spatial dexterity allows viewers of Tim Burton’s 2007 film adaptation to experience the same scene as a sequence of fifty-nine viewpoints, each of which isolate and emphasize distinct meanings and perspectives, including Sweeney Todd’s (Johnny Depp’s) point of view as he gets his first glimpse of his long-lost tools of the trade [2]; his emotional reaction as he contemplates righteous murder [3]; the razor replacing Mrs. Lovett (Helena Bonham Carter) as the focus of his attention [4]; and a dizzying simulated camera move that starts with the vengeful antihero [5], then pulls back to reveal the morally corrupt city he (and his razors) will soon terrorize [6]. A chemist breaks down a compound substance into its constituent parts to learn more than just a list of ingredients. The goal usually extends to determining how the identified individual components work together toward some sort of outcome: What is it about this particular mixture that makes it taste like strawberries, or grow hair, or kill cockroaches? Likewise, film analysis involves more than breaking down a sequence, a scene, or an entire movie to identify the tools and techniques that comprise it; the investigation is also concerned with the function and potential effect of that combination: Why does it make you laugh, or prompt you to tell your friend to see it, or incite you to join the Peace Corps? The search for answers to these sorts of questions boils down to one essential inquiry: What does it mean? For the rest of the chapter, we’ll explore film analysis by applying that question to three very different movies: first, and most extensively, the 2007 independent film Juno, and then the blockbusters Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Parts 1 and 2. Unfortunately, or perhaps intriguingly, not all movie meaning is easy to see. As we mentioned earlier, movies have a way of hiding their methods and meaning. So before we dive into specific approaches to analysis, let’s wade a little deeper into this whole notion of hidden, or “invisible,” meaning. Invisibility and Cinematic Language The moving aspect of moving pictures is one reason for this invisibility. Movies simply move too fast for even the most diligent viewers to consciously consider everything they’ve seen. When we read a book, we can pause to ponder the meaning or significance of any word, sentence, or passage. Our eyes often flit back to review something we’ve already read in order to further comprehend its meaning or to place a new passage in context. Similarly, we can stand and study a painting or sculpture or photograph for as long as we require in order to absorb whatever meaning we need or want from it. But up until very recently, the moviegoer’s relationship with every cinematic composition has been transitory. We experience a movie shot—which is capable of delivering multiple layers of visual and auditory information—for the briefest of moments before it is taken away and replaced with another moving image and another and another. If you’re watching a movie the way it’s designed to be experienced, there’s no time to contemplate any single movie moment’s various potential meanings. Recognizing a spectator’s tendency (especially when sitting in a dark theater, staring at a large screen) to identify subconsciously with the camera’s viewpoint, early filmmaking pioneers created a film grammar (or cinematic language) that draws upon the way we automatically interpret visual information in our real lives, thus allowing audiences to absorb movie meaning intuitively … and instantly. The fade-out/fade-in is one of the most straightforward examples of this phenomenon. When such a transition is meant to convey a passage of time between scenes, the last shot of a scene grows gradually darker (“fades out”) until the screen is rendered black for a moment. The first shot of the subsequent scene then “fades in” out of the darkness. The viewer doesn’t have to think about what this means; our daily experience of time’s passage marked by the Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 1 Ways of Looking at Movies setting and rising of the sun lets us understand intuitively that significant story time has elapsed over that very brief moment of screen darkness. A low-angle shot communicates in a similarly hidden fashion. When, near the end of Juno (Jason Reitman, 2007), we see the title character happily transformed back into a “normal” teenager, our sense of her newfound empowerment is heightened by the low angle from which this (and the next) shot is captured. Viewers’ shared experience of literally looking up at powerful figures—people on stages, at podiums, memorialized in statues, or simply bigger than them—sparks an automatic interpretation of movie subjects seen from this angle as, depending on context, either strong, noble, or threatening. This is all very well; the immediacy of cinematic language is what makes movies one of the most visceral experiences that art has to offer. The problem is that it also makes it all too easy to take movie meaning for granted. The relatively seamless presentation of visual and narrative information found in most movies can also cloud our search for movie meaning. In order to exploit cinema’s capacity for transporting audiences into the world of the story, the commercial filmmaking process stresses a polished continuity of lighting, performance, costume, makeup, and movement to smooth transitions between shots and scenes, thus minimizing any distractions that might remind viewers that they are watching a highly manipulated, and manipulative, artificial reality. Cutting on action is one of the most common editing techniques designed to hide the instantaneous and potentially jarring shift from one camera viewpoint to another. When connecting one shot to the next, a film editor will often end the first shot in the middle of a continuing action and start the connecting shot at some point in the same action. As a result, the action flows so continuously over the cut between different moving images that most viewers fail to register the switch. As with all things cinematic, invisibility has its exceptions. From the earliest days of moviemaking, innovative filmmakers have rebelled against the notion of hidden structures and meaning. The pioneering Soviet filmmaker and theorist Sergei Eisenstein believed that every edit, far from being invisible, should be very noticeable—a clash or collision of contiguous shots, rather than a seamless transition from one shot to the next. Filmmakers whose work is labeled “experimental”—inspired by Eisenstein and other predecessors—embrace self-reflexive styles that confront and confound conventional notions of continuity. Even some commercial films use techniques that undermine invisibility: in The Limey (1999), for example, Hollywood filmmaker Steven Soderbergh deliberately jumbles spatial and chronological continuity, forcing the spectator to actively scrutinize the cinematic structures on-screen in order to assemble, and thus comprehend, the story. But most scenes in most films that most of us watch rely heavily on largely invisible techniques that convey meaning intuitively. That’s not to say that cinematic language is impossible to spot; you simply have to know what you’re looking for. And soon, you will. The rest of this book is dedicated to helping you to identify and appreciate each of the many different secret ingredients that movies blend to convey meaning. And, luckily for you, motion pictures have been liberated from the imposed impermanence that helped create all this cinematic invisibility in the first place. Thanks to DVDs, Blu-rays, DVRs, and streaming video, you can now watch a movie much the same way you read a book: pausing to scrutinize, ponder, or review as necessary. This relatively new relationship between movies and viewers will surely spark new approaches to cinematic language and attitudes toward invisibility. That’s for future filmmakers, including maybe you, to decide. For now, these viewing technologies allow students of film like yourself to study movies with a lucidity and precision that was impossible for your predecessors. But not even repeated DVD viewings can reveal those movie messages hidden by our own preconceptions and belief systems. Before we can detect and interpret these meanings, we must first be aware of the ways expectations and cultural traditions obscure what movies have to say. Cultural Invisibility The same commercial instinct that inspires filmmakers to use seamless continuity also compels them to favor stories and themes that reinforce viewers’ shared belief systems. After all, the film industry, for the most part, seeks to entertain, not to provoke, its customers. A key to entertaining one’s customers is to “give them what they want”—to Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 2 Ways of Looking at Movies tap into and reinforce their most fundamental desires and beliefs. Even movies deemed “controversial” or “provocative” can be popular if they trigger emotional responses from their viewers that reinforce yearnings or beliefs that lie deep within. And because so much of this occurs on an unconscious, emotional level, the casual viewer may be blind to the implied political, cultural, and ideological messages that help make the movie so appealing. Of course, this cultural invisibility is not always a calculated decision on the part of the filmmakers. Directors, screenwriters, and producers are, after all, products of the same society inhabited by their intended audience. Oftentimes, the people making the movies may be just as oblivious of the cultural attitudes shaping their cinematic stories as the people who watch them. Juno’s filmmakers are certainly aware that their film—which addresses issues of abortion and pregnancy—diverges from the ways that movies traditionally represent family structures and teenage girls. In this sense, the movie might be seen as resisting common cultural values. But what they may not be as conscious of is the way their protagonist (main character) reinforces our culture’s celebration of the individual. Her promiscuous, forceful, and charming persona is familiar because it displays traits we often associate with Hollywood’s dominant view of the (usually male) rogue hero. Like Sam Spade, the Ringo Kid, Dirty Harry, and countless other classic American characters, Juno rejects convention yet ultimately upholds the very institutions she seemingly scorns. Yes, she’s a smart-ass who cheats on homework, sleeps with her best friend, and pukes in her stepmother’s decorative urn, yet in the end she does everything in her power to create the traditional nuclear family she never had. So even as the movie seems to call into question some of contemporary America’s attitudes about family, its appeal to an arguably more fundamental American value (namely, robust individualism) explains in part why, despite its controversial subject matter, Juno was (and is) so popular with audiences. Cultural invisibility in Juno An unrepentant former stripper (Diablo Cody) writes a script about an unrepentantly pregnant sixteen year old, her blithely accepting parents, and the dysfunctional couple to whom she relinquishes her newborn child. The resulting film goes on to become one of the biggest critical and box-office hits of 2007, attracting viewers from virtually every consumer demographic. How did a movie based on such seemingly provocative subject matter appeal to such a broad audience? One reason is that, beneath its veneer of controversy, Juno repeatedly reinforces mainstream, even conservative, societal attitudes toward pregnancy, family, and marriage. Although Juno initially decides to abort the pregnancy, she quickly changes her mind. Her parents may seem relatively complacent when she confesses her condition, but they support, protect, and advise her throughout her pregnancy. When we first meet Mark (Jason Bateman) and Vanessa (Jennifer Garner), the prosperous young couple Juno has chosen to adopt her baby, it is with the youthful Mark [1] that we (and Juno) initially sympathize. He plays guitar and appreciates alternative music and vintage slasher movies. Vanessa, in comparison, comes off as a shallow and judgmental yuppie. But ultimately, both the movie and its protagonist side with the traditional values of motherhood and responsibility embodied by Vanessa [2], and reject Mark’s rock-star ambitions as immature and self-centered. Implicit and Explicit Meaning As we attempt to become more skilled at looking at movies, we should try to be alert to the cultural values, shared ideals, and other ideas that lie just below the surface of the movie we’re looking at. Being more alert to these things will make us sensitive to, and appreciative of, the many layers of meaning that any single movie contains. Of course, all this talk of “layers” and the notion that much of a movie’s meaning lies below the surface may make the entire process of looking at movies seem unnecessarily complex and intimidating. But you’ll find that the process of observing, identifying, and interpreting movie meaning will become considerably less mysterious and complicated once you grow accustomed to actively looking at movies rather than just watching them. It might help to keep in mind that, no matter how many different layers of meaning there may be in a movie, each layer is either implicit or explicit. Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 3 Ways of Looking at Movies An implicit meaning, which lies below the surface of a movie’s story and presentation, is closest to our everyday sense of the word meaning. It is an association, connection, or inference that a viewer makes on the basis of the explicit meanings available on the surface of the movie. To get a sense of the difference between these two levels of meaning, let’s look at two statements about Juno. First, let’s imagine that a friend who hasn’t seen the movie asks us what the film is about. Our friend doesn’t want a detailed plot summary; she simply wants to know what she’ll see if she decides to attend the movie. In other words, she is asking us for a statement about Juno’s explicit meaning. You might respond to her question by explaining: “The movie’s about a rebellious but smart sixteen-year-old girl who gets pregnant and resolves to tackle the problem head on. At first, she decides to get an abortion; but after she backs off that choice, she gets the idea to find a couple to adopt the kid after it’s born. She spends the rest of the movie dealing with the implications of that choice.” This isn’t to say that this is the only explicit meaning in the film, but we can see that it is a fairly accurate statement about one meaning that the movie explicitly conveys to us, right there on its surface. Now what if our friend hears this statement of explicit meaning and asks, “Okay, sure, but what do you think the movie is trying to say? What does it mean?” In a case like this, when someone is asking in general about an entire film, he or she is seeking something like an overall message or a “point.” In essence, our friend is asking us to interpret the movie—to say something arguable about it—not simply to make a statement of obvious surface meaning that everyone can agree on, as we did when we presented its explicit meaning. In other words, she is asking us for our sense of the movie’s implicit meaning. One possible response might be: “A teenager faced with a difficult decision makes a bold leap toward adulthood but, in doing so, discovers that the world of adults is no less uncertain or overwhelming than adolescence.” At first glance, this statement might seem to have a lot in common with our summary of the movie’s explicit meaning, as, of course, it does—after all, even though a meaning is under the surface, it nonetheless has to relate to the surface, and our interpretation needs to be grounded in the explicitly presented details of that surface. But if you compare the two statements more closely, you can see that the second one is more interpretive than the first, more concerned with what the movie “means.” Explicit and implicit meanings need not pertain to the movie as a whole, and not all implicit meaning is tied to broad messages or themes. Movies convey and imply smaller, more specific doses of both kinds of meaning in virtually every scene. Juno’s application of lipstick before she visits the adoptive father, Mark, is explicit information. The implications of this action—that her admiration for Mark is beginning to develop into something approaching a crush—are implicit. Later, Mark’s announcement that he is leaving his wife and does not want to be a father sends Juno into a panicked retreat. On her drive home, a crying jag forces the disillusioned Juno to pull off the highway. She skids to a stop beside a rotting boat abandoned in the ditch. The discarded boat’s decayed condition and the incongruity of a watercraft adrift in an expanse of grass are explicit details that convey implicit meaning about Juno’s isolation and alienation. Explicit detail and implied meaning in Juno Vanessa is the earnest yuppie mommy-wannabe to whom Juno has promised her baby. In contrast to the formal business attire she usually sports, Vanessa wears an Alice in Chains Tshirt to paint the nursery. This small explicit detail conveys important implicit meaning about her relationship with her husband, Mark, a middle-aged man reluctant to let go of his rock-band youth. The paint-spattered condition of the old shirt implies that she no longer values this symbol of the 1980s grunge-rock scene and, by extension, her past association with it. It’s easy to accept that recognizing and interpreting implicit meaning requires some extra effort, but keep in mind that explicit meaning cannot be taken for granted simply because it is by definition obvious. Although explicit meaning is on the surface of a film for all to observe, it is unlikely that every viewer or writer will remember and acknowledge every part of that meaning. Because movies are rich in plot detail, a good analysis must begin by taking into account the breadth and diversity of what has been explicitly presented. For example, we cannot fully appreciate the significance of Juno’s defiant dumping of a blue slushy into her stepmother’s beloved urn unless we have noticed and noted her dishonest denial when accused earlier of vomiting a similar substance into the same precious vessel. Our ability to discern a movie’s explicit meanings is directly dependent on our ability to notice such associations and relationships. Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 4 Ways of Looking at Movies Viewer Expectations The discerning analyst must also be aware of the role expectations play in how movies are made, marketed, and received. Our experience of nearly every movie we see is shaped by what we have been told about that movie beforehand by previews, commercials, reviews, interviews, and word of mouth. After hearing your friends rave endlessly about Juno, you may have been underwhelmed by the actual movie. Or you might have been surprised and charmed by a film you entered with low expectations, based on the inevitable backlash that followed the movie’s surprise success. Even the most general knowledge affects how we react to any given film. We go to see blockbusters because we crave an elaborate special-effects extravaganza. We can still appreciate a summer movie’s relatively simpleminded storytelling, as long as it delivers the promised spectacle. On the other hand, you might revile a high-quality tragedy if you bought your ticket expecting a lighthearted comedy. Of course, the influence of expectation extends beyond the kind of anticipation generated by a movie’s promotion. As we discussed earlier, we all harbor essential expectations concerning a film’s form and organization. And most filmmakers give us what we expect: a relatively standardized cinematic language, seamless continuity, and a narrative organized like virtually every other fiction film we’ve ever seen. For example, years of watching movies has taught us to expect a clearly motivated protagonist to pursue a goal, confronting obstacles and antagonists along the way toward a clear (and usually satisfying) resolution. Sure enough, that’s what we get in most commercial films. We’ll delve more deeply into narrative in the chapters that follow. For now, what’s important is that you understand how your experience—and, thus, your interpretation—of any movie is affected by how the particular film manipulates these expected patterns. An analysis might note a film’s failure to successfully exploit the standard structures or another movie’s masterful subversion of expectations to surprise or mislead its audience. A more experimental approach might deliberately confound our presumption of continuity or narrative. The viewer must be alert to these expected patterns in order to fully appreciate the significance of that deviation. Expectations specific to a particular performer or filmmaker can also alter the way we perceive a movie. For example, any fan of actor Michael Cera’s previous performances as an endearingly awkward adolescent in the film Superbad (Greg Mottola, 2007) and television series Arrested Development (2003–2006) will watch Juno with a built-in affection for Paulie Bleeker, Juno’s sort-of boyfriend. This predetermined fondness does more than help us like the movie; it dramatically changes the way we approach a character type (the high-school athlete who impregnates his teenage classmate) that our expectations might otherwise lead us to distrust. Ironically, audience expectations of Cera’s sweetness may have contributed to the disappointing box-office performance of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010, Edgar Wright). Some critics proposed that viewers were uncomfortable seeing Cera play the somewhat vain and self-centered title character. Viewers who know director Guillermo del Toro’s commercial action/horror movies Mimic (1997), Blade II (2002), and Hellboy (2004) might be surprised by the sophisticated political and philosophical metaphor of Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) or The Devil’s Backbone (2001). Yet all five films feature fantastic and macabre creatures as well as social commentary. An active awareness of an audience’s various expectations of del Toro’s films would inform an analysis of the elements common to the filmmaker’s seemingly schizophrenic body of work. Such an analysis could focus on his visual style in terms of production design, lighting, or special effects, or might instead examine recurring themes such as oppression, childhood trauma, or the role of the outcast. Expectations and character in Juno Audience reactions to Michael Cera’s characterization of Juno’s sort-of boyfriend, Paulie Bleeker, are colored by expectations based on the actor’s perpetually embarrassed persona established in previous roles in the television series Arrested Development and films like Superbad [1]. We don’t need the movie to tell us much of anything about Paulie—we form an almost instant affection for the character based on our familiarity with Cera’s earlier performances. But while the character Paulie meets our expectations of Michael Cera, he defies our expectations of his character type. Repeated portrayals of high-school jocks as vain bullies, such as Thomas F. Wilson’s iconic Biff in Robert Zemeckis’s Back to the Future (1985) [2] have conditioned viewers to expect such characters to look and behave very differently than Paulie Bleeker. Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 5 Ways of Looking at Movies As you can see, cinematic invisibility is not necessarily an impediment; once you know enough to acknowledge their existence, these potential blind spots also offer opportunities for insight and analysis. There are many ways to look at movies and many possible types of film analysis. We’ll spend the rest of this chapter discussing the most common analytical approaches to movies. Since this book considers an understanding of how film grammar conveys meaning, mood, and information as the essential foundation for any further study of cinema, we’ll start with formal analysis—that analytical approach primarily concerned with film form, or the means by which a subject is expressed. Don’t worry if you don’t fully understand the function of the techniques discussed; that’s what the rest of this book is for. Formal Analysis Formal analysis dissects the complex synthesis of cinematography, sound, composition, design, movement, performance, and editing orchestrated by creative artists like screenwriters, directors, cinematographers, actors, editors, sound designers, and art directors, as well as the many craftspeople who implement their vision. The movie meaning expressed through form ranges from narrative information as straightforward as where and when a particular scene takes place to more subtle implied meaning, such as mood, tone, significance, or what a character is thinking or feeling. While it is certainly possible for the overeager analyst to read more meaning into a particular visual or audio component than the filmmaker intended, you should realize that cinematic storytellers exploit every tool at their disposal and that, therefore, every element in every frame is there for a reason. It’s up to the analyst to carefully consider the narrative intent of the moment, scene, or sequence before attempting any interpretation of the formal elements used to communicate that intended meaning to the spectator. For example, the simple awareness that Juno’s opening shot is the first image of the movie informs the analyst of the moment’s most basic and explicit intent: to convey setting (contemporary middle-class suburbia) and time of day (dawn). But only after we have determined that the story opens with its title character overwhelmed by the prospect of her own teenage pregnancy are we prepared to deduce how this implicit meaning (her state of mind) is conveyed by the composition: Juno is at the far left of the frame and is tiny in relationship to the rest of the wide-angle composition. In fact, we may be well into the four-second shot before we even spot her. Her vulnerability is conveyed by the fact that she is dwarfed by her surroundings. Even when the scene cuts to a closer viewpoint [2], she, as the subject of a movie composition, is much smaller in frame than we are used to seeing, especially in the first shots used to introduce a protagonist. The fact that she is standing in a front yard contemplating an empty stuffed chair from a safe distance, as if the inanimate object might attack at any moment, adds to our implicit impression of Juno as alienated or off-balance. Our command of the film’s explicit details alerts us to another function of the scene: to introduce the recurring theme (or motif) of the empty chair that frames—and in some ways defines—the story. In this opening scene, accompanied by Juno’s voice-over explanation, “It started with a chair,” the empty, displaced object represents Juno’s status and emotional state, and foreshadows the unconventional setting for the sexual act that got her into this mess. By the story’s conclusion, when Juno announces, “It ended with a chair,” the motif—in the form of an adoptive mother’s rocking chair—has been transformed, like Juno herself, to embody hope and potential. All that meaning was packed into two shots spanning about twelve seconds of screen time. Let’s see what we can learn from a formal analysis of a more extended sequence from the same film: Juno’s visit to the Women Now clinic. To do so, we’ll first want to consider what information the filmmaker needs this scene to communicate for viewers to understand and appreciate this pivotal piece of the movie’s story in relation to the rest of the narrative. As we delve into material that deals with Juno’s sensitive subject matter, we must keep in mind that we don’t have to agree with the meaning or values projected by the object of our analysis; one is not required to like a movie in order to learn from it. Our own values and beliefs will undoubtedly influence our analysis of any movie. Our personal views provide a legitimate perspective, as long as we recognize and acknowledge how they may color our interpretation. Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 6 Ways of Looking at Movies In this tutorial, Dave Monahan analyzes the “waiting room” scene from Juno and covers other key concepts of film analysis. Throughout Juno’s previous eighteen minutes, all information concerning its protagonist’s attitude toward her condition has explicitly enforced our expectation that she will end her unplanned pregnancy with an abortion. She pantomimes suicide once she’s forced to admit her condition; she calmly discusses abortion facilities with her friend Leah; she displays no ambivalence when scheduling the procedure. Approaching the clinic, Juno’s nonchalant reaction to the comically morose pro-life demonstrator Su-Chin reinforces our aforementioned expectations. Juno treats Su-Chin’s assertion that the fetus has fingernails as more of an interesting bit of trivia than a concept worthy of serious consideration. The subsequent waiting-room sequence is about Juno making an unexpected decision that propels the story in an entirely new direction. A formal analysis will tell us how the filmmakers orchestrated multiple formal elements, including sound, composition, moving camera, and editing, to convey in thirteen shots and thirty seconds of screen time how the seemingly insignificant fingernail factoid infiltrates Juno’s thoughts and ultimately drives her from the clinic. By the time you have completed your course (and have read the book), you should be prepared to apply this same sort of formal analysis to any scene you choose. The waiting-room sequence’s opening shot dollies in (the camera moves slowly toward the subject), which gradually enlarges Juno in frame, increasing her visual significance as she fills out the clinic admittance form on the clipboard in her hand. The shot reestablishes her casual acceptance of the impending procedure, providing context for the events to come. Its relatively long ten-second duration sets up a relaxed rhythm that will shift later along with her state of mind. As the camera reaches its closest point, a loud sound invades the low hum of the previously hushed waiting room. This obtrusive drumming sound motivates a somewhat startling cut to a new shot that plunges our viewpoint right up into Juno’s face. The sudden spatial shift gives the moment resonance and conveys Juno’s thought process as she instantly shifts her concentration from the admittance form to this strange new sound. She turns her head in search of the sound’s source, and the camera adjusts to adopt her point of view of a mother and daughter sitting beside her. The mother’s fingernails drumming on her own clipboard is revealed as the source of the tapping sound. The sound’s abnormally loud level signals that we’re not hearing at a natural volume level—we’ve begun to experience Juno’s psychological perceptions. The little girl’s stare into Juno’s (and our) eyes helps to establish the association between the fingernail sound and Juno’s latent guilt. The sequence cuts back to the already troubled-looking Juno. The juxtaposition connects her anxious expression to both the drumming mother and the little girl’s gaze. The camera creeps in on her again. This time, the resulting enlargement keys in our intuitive association of this gradual intensification with a character’s moment of realization. Within half a second, another noise joins the mix, and Juno’s head turns in response. The juxtaposition marks the next shot as Juno’s point of view, but it is much too close to be her literal point of view. Like the unusually loud sound, the unrealistically close viewpoint of a woman picking her thumbnail reflects not an actual spatial relationship but the sight’s significance to Juno. When we cut back to Juno about a second later, the camera continues to close in on her, and her gaze shifts again to follow yet another sound as it joins the rising clamor. A new shot of another set of hands, again from a close-up, psychological point of view, shows a woman applying fingernail polish. What would normally be a silent action emits a distinct, abrasive sound. When we cut back to Juno half a second later, she is much larger in the frame than the last few times we saw her. This break in pattern conveys a sudden intensification; this is really starting to get to her. Editing often establishes patterns and rhythms, only to break them for dramatic impact. Our appreciation of Juno’s situation is enhanced by the way editing connects her reactions to the altered sights and sounds around her, as well as by her implied isolation—she appears to be the only one who notices the increasingly boisterous symphony of fingernails. Of Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 7 Ways of Looking at Movies course, Juno’s not entirely alone—the audience is with her. At this point in the sequence, the audience has begun to associate the waiting-room fingernails with Su-Chin’s attempt to humanize Juno’s condition. Juno’s head jerks as yet another, even more invasive sound enters the fray. We cut to another close-up point-of-view shot, this time of a young man scratching his arm. At this point, another pattern is broken, initiating the scene’s formal and dramatic climax. Up until now, the sequence alternated between shots of Juno and shots of the fingernails as they caught her attention. Each juxtaposition caused us to identify with both Juno’s reaction and her point of view. But now, the sequence shifts gears; instead of the expected switch back to Juno, we are subjected to an accelerating succession of fingernail shots, each one shorter and louder than the last. A woman bites her fingernails; another files her nails; a woman’s hand drums her fingernails nervously; a man scratches his neck. With every new shot, another noise is added to the sound mix. This pattern is itself broken in several ways by the scene’s final shot. We’ve grown accustomed to seeing Juno look around every time we see her, but this time, she stares blankly ahead, immersed in thought. A cacophony of fingernail sounds rings in her (and our) ears as the camera glides toward her for three and a half very long seconds— a duration six times longer than any of the previous nine shots. These pattern shifts signal the scene’s climax, which is further emphasized by the moving camera’s enlargement of Juno’s figure, a visual action that cinematic language has trained viewers to associate with a subject’s moment of realization or decision. But the shot doesn’t show us Juno acting on that decision. We don’t see her cover her ears, throw down her clipboard, or jump up from the waiting-room banquette. Instead, we are ripped prematurely from this final waitingroom image and are plunged into a shot that drops us into a different space and at least several moments ahead in time—back to Su-Chin chanting in the parking lot. This jarring spatial, temporal, and visual shift helps us feel Juno’s own instability at this crucial narrative moment. Before we can get our bearings, the camera has pivoted right to reveal Juno bursting out of the clinic door in the background. She races past Su-Chin without a word. She does not have to say anything. Cinematic language—film form—has already told us what she decided and why. Anyone watching this scene would sense the narrative and emotional meaning revealed by this analysis, but only a viewer actively analyzing the film form used to construct it can fully comprehend how the sophisticated machinery of cinematic language shapes and conveys that meaning. Formal analysis is fundamental to all approaches to understanding and engaging cinema—whether you’re making, studying, or simply appreciating movies—which is why the elements and grammar of film form are the primary focus of Looking at Movies. Alternative Approaches to Analysis Although we’ll be looking at movies primarily in terms of the forms they take and the nuts and bolts from which they are constructed, any serious student of film should be aware that there are many other legitimate frameworks for analysis. These alternative approaches analyze movies more as cultural artifacts than as traditional works of art. They search beneath a movie’s form and content to expose implicit and hidden meanings that inform our understanding of cinema’s function within popular culture as well as the influence of popular culture on the movies. The preceding formal analysis demonstrated how Juno used cinematic language to convey meaning and tell a story. Given the right interpretive scrutiny, our case study film may also speak eloquently about social conditions and attitudes. For example, considering that the protagonist is the daughter of an air-conditioner repairman and a manicurist, and that the couple she selects to adopt her baby are white-collar professionals living in an oversized McMansion, a cultural analysis of Juno could explore the movie’s treatment of class. An analysis from a feminist perspective could concentrate on, among other elements, the movie’s depiction of women and childbirth, not to mention Juno’s father, the father of her baby, and the prospective adoptive father. Such an analysis might also consider the creative and ideological contributions of the movie’s female screenwriter, Diablo Cody, an outspoken former stripper and sex blogger. A linguistic analysis might explore the historical, cultural, or imaginary origins of the highly stylized slang spouted by Juno, her friends, even the mini-mart clerk who sells her a pregnancy test. A thesis could be (and probably has been) written about the implications of the T-shirt messages displayed by the film’s characters or the implicit meaning of the movie’s running-track-team motif. Some analyses place movies Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 8 Ways of Looking at Movies within the stylistic or political context of a director’s career. Juno’s young director, Jason Reitman, has made only three other feature films. But even that relatively short filmography provides opportunity for comparative analysis: all of Reitman’s movies take provocative political stances, gradually generate empathy for initially unsympathetic characters, and favor fast-paced expositional montages featuring expressive juxtapositions, graphic compositions, and first-person voiceover narration. Another comparative analysis could investigate society’s evolving (or perhaps fixed) attitudes toward “illegitimate” pregnancy by placing Juno in context with the long history of films about the subject, from D. W. Griffith’s 1920 silent drama Way Down East, which banished its unwed mother and drove her to attempted suicide, to Preston Sturges’s irreverent 1944 comedy The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek and its mysteriously pregnant protagonist, Trudy Kockenlocker (whose character name alone says a great deal about its era’s attitudes toward women), to another mysterious, but ultimately far more terrifying, pregnancy in Roman Polanski’s 1968 horror masterpiece Rosemary’s Baby. Juno is only one of a small stampede of recent popular films dealing with this seemingly evertimely issue. A cultural analysis might compare and contrast Juno with its American contemporaries Knocked Up (Judd Apatow, 2007) and Waitress (Adrienne Shelly, 2007), both of which share Juno’s blend of comedy and drama, as well as a pronounced ambivalence concerning abortion, but depict decidedly different characters, settings, and stories. What might such an analysis of these movies (and their critical and popular success) tell us about our own particular era’s attitudes toward women, pregnancy, and motherhood? Knocked Up is written and directed by a man, Juno is written by a woman and directed by a man, Waitress is written and directed by a woman. Does the relative gender of each film’s creator affect those attitudes? If this comparative analysis incorporated Romanian filmmaker Cristian Mungiu’s stark abortion drama 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007) or Mike Leigh’s nuanced portrayal of the abortionist Vera Drake (2004), the result might inform a deeper understanding of the differences between European and American sensibilities. An unwanted pregnancy is a potentially controversial subject for any film, especially when the central character is a teenager. Any extensive analysis focused on Juno’s cultural meaning would have to address what this particular film’s content implies about the hot-button issue of abortion. By way of illustration, let’s return to the clinic waiting room. An analysis that asserts Juno espouses a “pro-life” (i.e., anti-abortion) message could point to several explicit details in this sequence and to those preceding and following it. In contrast to the relatively welcoming suburban settings that dominate the rest of the story, the ironically named Women Now abortion clinic is an unattractive stone structure squatting at one end of an urban asphalt parking lot. Juno is confronted by clearly stated and compelling arguments against abortion via Su-Chin’s dialogue: the “baby” has a beating heart, can feel pain, … and has fingernails. The clinic receptionist, the sole on-screen representative of the pro-choice alternative, is a sneering cynic with multiple piercings and a declared taste for fruit-flavored condoms. The idea of the fetus as a human being, stressed by Su-Chin’s earnest admonishments, is driven home by the scene’s formal presentation analyzed earlier. On the other hand, a counterargument maintaining that Juno implies a pro-choice stance could state that the lone onscreen representation of the pro-life position is portrayed just as negatively (and extremely) as the clinic receptionist. Su-Chin is presented as an infantile simpleton who wields a homemade sign stating, rather clumsily, “No Babies Like Murdering,” shouts “All babies want to get borned!” and is bundled in an oversized stocking cap and pink quilted coat as if dressed by an overprotective mother. Juno’s choice can hardly be labeled a righteous conversion. Even after fleeing the clinic, the clearly ambivalent mother-to-be struggles to rationalize her decision, which she announces not as “I’m having this baby” but as “I’m staying pregnant.” Some analysts may conclude that the filmmakers, mindful of audience demographics, were trying to have it both ways. Others could argue that the movie is understandably more concerned with narrative considerations than a precise political stance. The negative aspects of every alternative are consistent with a story world that offers its young protagonist little comfort and no easy choices. Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 9 Ways of Looking at Movies Cultural and Formal Analysis in Harry Potter The preceding discussion demonstrates that a popular mainstream entertainment like Juno offers ample material for analysis. But are popular movies worthy of this sort of scholarly attention? After all, isn’t serious intellectual inquiry supposed to be reserved for art films—the more difficult and obscure, the better? Although film scholars often do study unconventional movies that most people have never heard of, many of these same scholars pay special attention to blockbusters and other popular entertainments. Why do they do this? To begin with, they may seek the answer to an obvious question: why do audiences like this movie? Or, to take it a step further, they may try to analyze the movie’s form, themes, and messages to better understand how those elements might explain the movie’s popularity with contemporary audiences. But why is this sort of analysis important? Stated plainly: because movies are influential. The more consumers see a movie—or even just see the advertising and witness public reaction to its success—the more likely it is that that movie will exert some kind of effect on those consumers’ culture. Any movie capable of influencing society is surely worth a closer look. For example: few cinematic figures have been so ubiquitous for so long as Harry Potter. Since 2001, the Harry Potter franchise has produced eight hit films that together earned over $7 billion worth of worldwide ticket sales,1 a staggering figure that doesn’t even include the additional exposure and revenue generated by DVD, pay-per-view, streaming video, and other sales of the movies. Clearly, the Harry Potter series is an influential and important cultural phenomenon. But how can we even begin to explain its popularity? To start with, the sheer scope of the series provides viewers a particular brand of narrative development unavailable in most movies or film series. If we stop to consider other well-known film series, few if any of them feature any significant figurative or literal character growth. Consider Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings or Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean or even Luke Skywalker in the original Star Wars trilogy. Although they accomplish extraordinary feats in spectacular adventures, all of these leading characters act and look much the same from the first movie to the final installment. In contrast, Harry Potter and his classmates literally grow up on-screen. Watching (and anticipating) Harry (Daniel Radcliffe), Hermione (Emma Watson), and Ron (Rupert Grint) develop from innocent children to moody adolescents to world-weary but resolute young adults provides viewers a participatory pleasure that compels them to see the next movie, as well as rewatch and compare earlier installments. An analyst studying the appeal of the Harry Potter movies would likely examine the role nostalgia plays in the story and its visual presentation. Instead of computers, smart phones, or video games, the wizarding world of Harry Potter features puzzles, riddles, and Quidditch. Although the story is set in the 1990s, the movies’ design schemes are a pastiche of more distant and romanticized pasts. The look of the Hogwarts boarding school and much of its eccentric faculty suggests the Middle Ages; many character costumes, including the Hogwarts school uniforms and the office attire favored by the Ministry of Magic, evoke fashions from the 1940s. The visual associations with the World War II era are one piece of evidence that the series connects with audiences by tapping into a shared cultural and political experience. Lord Voldemort may not look like Adolf Hitler, but he does rule by fear, is bent on world domination, and exploits a racist ideal of “pure blood” to intimidate and inspire his growing legions of followers. The fictional struggle against Voldemort has a trajectory similar to the historic struggle against Hitler: Complacency delays resistance until almost too late, but the forces of reason finally unite to stand up to the evil megalomaniac, who is ultimately undone by his own hubris. Voldemort exploits the weaker characters’ need to belong to the winning team; the character of Harry Potter appeals to an essential human longing to be special. A narrative analysis of the Potter films might explore Harry’s place in a classical storytelling tradition. He is an ordinary boy suddenly revealed as a chosen one with extraordinary hidden talents and a special destiny. This secret savior is plucked from obscurity, undergoes training, and is tested by a series of increasingly dangerous challenges. In the end, our unlikely hero defeats a seemingly invincible evil. This same description could be applied to characters at the heart of other recent popular serial adventures, including Neo in the Matrix movies and Luke Skywalker in the original Star Wars trilogy. Some scholars maintain that Jesus Christ belongs to the same narrative tradition; others may argue that the character type is in fact inspired by Christ’s actual Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 10 Ways of Looking at Movies experience. Regardless of one’s own religious beliefs, it’s hard to deny that Harry is a Christ figure of sorts. Perhaps this resemblance accounts for at least some of Harry’s resonance with audiences. After all, he’s not just anointed, questioned, betrayed, and redeemed. He also sacrifices himself, dies, and is resurrected. In the final film, Harry and Dumbledore’s radiant reunion on a luminous train platform visually reinforces the comparison. A cultural analysis of the Potter phenomenon might investigate if (and if so, how) these religious allusions influence the millions of viewers who have experienced the movies. Do audiences identify with Christian themes, or is the power of Potter purely narrative and cinematic? Many religiously-conservative critics of the series contend that the relationship between Harry Potter and Christianity is adversarial, not associative. They argue that the movies glamorize the occult and thus lure young people away from traditional religious values. Other observers argue that the fictional witchcraft of the Potter films is nothing more than an endorsement of imagination and individuality. We go to the movies for many reasons: to immerse ourselves in stories; to identify with interesting characters; to be enlightened or moved or simply distracted. But sometimes we also crave the kind of lavish visual extravaganza known as spectacle. Cinema’s unique capacity for conjuring fantastic images and action has enticed audiences since the silent film era. The abundance of on-screen magic that the Harry Potter movies provide has almost certainly contributed to the series’ commercial success. And that success was aided by fortuitous timing. The movie adaptations began at a time when the film industry was entering a digital revolution. As the story and characters grew increasingly sophisticated, so did special effects. Technology advanced to meet each new installment’s demands for greater cinematic wizardry. The visual extravaganza culminates in Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows: Part 2. The final episode delivers a roller-coaster chase sequence atop a runaway dragon, an epic battle sequence, a race to escape an animate (and animated) firestorm, and a wand duel to the death, all in 3-D. Of course, it takes more than spectacle to satisfy millions of viewers—especially for eight consecutive movies. Some of the series’ most engaging scenes employ a far more subtle approach to cinematic storytelling. Let’s close this introduction with a formal analysis of an unassuming but effective scene created specifically for the film Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows: Part 1. Frustrated and exhausted by worry and jealousy, Ron has walked out—leaving Harry and Hermione to carry on without him. They’re on the run, and their quest to find and destroy a series of enchanted objects (aka horcruxes) that safeguard the evil lord’s soul is going nowhere. In this scene, an impromptu dance momentarily breaks the oppressive tension and reaffirms and defines Harry and Hermione’s friendship. The opening shot [1] is the widest—in other words, it shows us the most space. We see the interior of Harry and Hermione’s dreary tent, as well as the literal (and figurative) distance between the troubled friends. The figures’ relative small size in relation to the space between and around them helps convey a sense of vulnerability. Harry trudges to his chair and sits to face Hermione, who does not return his gaze. Instead, she stares at Ron’s abandoned radio. Other than muffled wind and creaking floorboards, the radio is all we hear. The reception is spotty and the speaker is tinny, but we can just make out the song “O Children” (by Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds). Now that the mood and the state of the relationship have been established, the next shot [2] concentrates on Harry. He is large enough in the frame to allow us to easily read his defeated expression, and to register his stare at the offscreen Hermione. The camera creeps in on him, gradually increasing his size in the frame and thus lending significance to his expression. Something is on Harry’s mind. The next shot [3] confirms it. The scene shows us what Harry is thinking about, and looking at: Hermione, bigger in the frame and still hunched over Ron’s radio, which is still playing “O Children.” The song’s melancholy tone reinforces our characters’ mood; the radio’s thin sound and bad reception convey their isolation. When we cut back to Harry [4], he reacts to what he (and we) just saw in the previous point-of-view shot. It’s difficult to know exactly what he’s feeling, but he seems agitated—a feeling reinforced by the intensifying effects of the creeping camera, the back-and-forth cutting, the progressively tighter framing, and the crackling radio. Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 11 Ways of Looking at Movies The pattern continues as he stirs and the scene cuts back to a tightly framed, high-angle shot of Hermione. A moment after the shot begins, Harry steps into the foreground, momentarily obscuring Hermione [5a] before she reemerges and looks up to meet his implied gaze [5b]. Harry’s sudden looming appearance feels almost aggressive; the filmmakers are building tension and tickling our expectations. After all, we’re watching two anxious teenagers alone in an isolated tent; maybe Ron’s jealousy was justified after all. Harry looks down at the offscreen Hermione at the beginning of the next shot [6a]. The camera starts on his face, then drifts down to his outstretched hand [6b]. We cut back to Hermione [7a], who considers the offer. This moment brings the scene to a turning point that is both tantalizing and disturbing. Several things happen at once to provoke our expectations: Hermione takes Harry’s hand. As she stands, the camera follows her into a cozy composition in which the young witch and wizard stand face to face to share the frame for the first time since the scene’s first shot [7b]. Where that opening image implied distance, this shot emphasizes intimacy. Harry removes Hermione’s horcrux necklace (a gesture that propels us into the next equally intimate shot [8]). All of a sudden, Harry and Hermione are holding hands, staring into each others’ eyes, and taking off each others’ enchanted jewelry. This turn of events takes even those viewers who have read the books by surprise. This scene does not occur in the original novel. Could it be that Harry and Hermione are about to hook up? And something is happening with the scene’s sound to further stimulate this expectation. The wind and floorboard sounds disappear. What was once faint music drifting from a portable radio rises in volume and clarity until it dominates the sound track. “O Children” is no longer playing on the radio; it’s emanating from the movie itself. The swelling music seems to embody the characters’ escalating emotions. The potential sexual intensity persists in the next shot as Harry tosses the horcrux on Hermione’s bed and leads her, hand in hand into the foreground [9]. The cut to the next shot [10] provides a new angle on the couple as Harry coaxes Hermione to sway along to the still-swelling music. The pace of the sequence picks up as they begin to dance over the next four short shots: [11], [12], [13], and [14a]. Up until this point, the scene has maintained conventional continuity editing. Eye-line match cuts (when the direction a character looks corresponds with the angle of a point-of-view shot or another character’s responding look) or cutting on action smoothes each transition from one shot to the next. Each shift to a new perspective has been orchestrated to keep the viewer neatly oriented in space and time. Now the scene is about to shift gears, and the filmmakers use a shift in style to let us know it. The cut between shots 14b and 15 is a jump cut: a sudden “jump forward” in the action that intentionally defies our expectations of continuity. One moment, Harry is on the left side of the screen looking to the right toward Hermione [14b], but the cut pops him instantaneously into the middle of a twirl [15]. The next cut jumps forward again: suddenly it’s Hermione who’s twirling [16]. It’s as if the editor took a shot of the dance, snipped out a couple of pieces of the action, then stuck the remaining pieces back together again—which is essentially how most jump cuts are achieved. Defying the rules of continuity disorients the viewer, which is why this technique is often employed to convey chaos or confusion. But in this case, the technique defuses the tension and triggers a sort of giddy catharsis. With the aid of the music, the actors’ playful performances, and the rapid pace of the action and cutting, the discontinuity transforms what appeared to be a somber seduction into a good-natured game. The lighthearted mood continues through the next eight cuts, five of which are jump cuts. Harry and Hermione’s friendship has been threatened, confirmed, and celebrated over the course of twenty-three shots, ending with shots [17–23]. When continuity returns, so does grim reality. Shot 24 flows into shot 25 with a match on action—that is, a transition that moves seamlessly from the action in one shot to a continuation of that action in the next shot. The shots show Harry and Hermione’s whirling dance collapse into an affectionate, but strictly fraternal, hug shots [24] and [25a]. These close-up shots let us see the characters’ faces as they slow to a stop. The music fades along with their smiles as the gravity of their situation reasserts itself [25b]. Hermione walks out of shot 26, and the final image [27] is then a lingering close-up of Harry watching her go. The scene ends as it began: with our characters alone, outnumbered, and seemingly out of options. Barsam, Richard and Monahan, Dave. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2013. (p. 5-31) 12