a re-evaluation of predation on New World primates

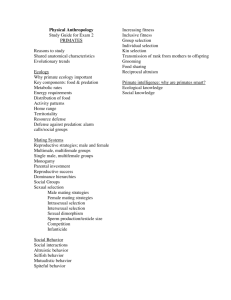

advertisement

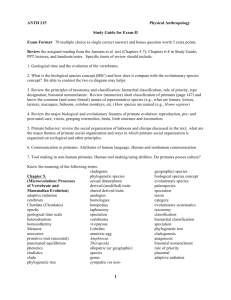

JASs Reports Journal of Anthropological Sciences Vol. 83 (2005), pp. 89-109 The targeted monkey: a re-evaluation of predation on New World primates Bernardo Urbani Department of Anthropology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 109 Davenport Hall, 607 S Mathews Ave., Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA, e-mail: burbani@uiuc.edu Summary – This work reviews the information related to predation on Neotropical primates by human and non-human predators. Paradoxically, humans have been systematically neglected while evaluating the potential effects of predation in the structure of non-human primate populations. Predation paradigms do not include humans in their propositions. In this review, it is shown that effectively humans are the main predators of monkey communities in the Neotropics. The results also suggest that humans do not fit with predation theoretical views given for non-human predators. Homo cultural hunting practices contribute to this situation. For example, humans seem to prefer larger primate groups that allow their location for hunting, or humans tend to prey primary larger monkeys with longer interbirth interval. In sum, it is suggested that since at least 11,000 years of human occupation in the Neotropics, Homo might have been played a fundamental role in the current organization and distribution of primate populations, including local extinctions. Humans seemed to have potentially influenced New World primate population in such short ecological time scale. Keywords – Predatory behavior, ethnoprimatology, human hunting, predation paradigms, transdisciplinary perspective, conservation, Latin America. Introduction “The indications are that man is the most serious enemy of howlers and that occasionally young animals may be attacked by ocelots” said Clarence Ray Carpenter in 1934 after observing mantled howler monkeys in Panama (Carpenter, 1934: 129). In fact, it was his last conclusion in the first systematic primate behavioral research conducted in the wild, and probably also the first scientific account of the impact of predators on feral primates. After this work, other researches have taken predation risk into account as a potential factor influencing the evolution of sociality in general, and the social structure of primate populations (e.g. Cheney & Wragham, 1987). For example, since the 1960s chimpanzees had been the subjects of the longest-term studies even carried out for any wild mammal; but paradoxically it was not until 1990, that the first case of predation on chimpanzees by lions was reported (Tsukahara & Nishida 1990). In addition, predation has been systematically cited in works of the natural history of primates (e. g. Kinzey, 1997); however, reports of predation are extreme scarce. In part, this relates to difficulties obtaining field data on predation because of its low rate and rapid occurrence. In addition, Isbell (1994) suggested that limited predation observation might be related to the observers (field primatologists) that are normally not present when main predators are active (at night) and the presence of the observer may inhibit the appearance of predators during the day. However, predation and predation risk have been considered important in modeling the structure and organization of the extant and extinct primate populations (see review: Isbell, 1994). In this sense, it has been argued that some “anti-predatory” behaviors such as vigilance, polyspecific associations, group cohesion, direct or active defense and alarm calls are related to the selective pressure of predation on primates (Cheney & Wragham, 1987; Isbell, 1994). Van Schaik & Horstermann (1994) proposed a hypothesis that suggested that the quantity of the JASs is published by the Istituto Italiano di Antropologia www.isita-org.com 90 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys primate males -and group composition- is not only related to sexual competition but also to predation risk. Their hypothesis predicts that males are more vigilant than females, and play a greater role in predator detection. In her literature review, Isbell (1994: 65-68) characterized five patterns of predation on primates. These patterns are, 1) larger primates are expected to be less vulnerable to predation than are smaller primates; 2) an individual’s vulnerability to predation increased in unknown or unfamiliar areas (for a definition of vulnerability, see below: Miller, 2002); 3) primates are more vulnerable in the upper canopy, in discontinuous forests and on the forest edges than in continuous, undisturbed forests; 4) predation is episodic and may be related to prey preferences and different use of daily ranges and home ranges between predators and prey; and 5) terrestrial primates have higher rates and risk of predation than do arboreal primates. In addition, Chapman (2000) reviewed the predation avoidance hypothesis by examining patterns of group structure and movement in 54 primate species. He argued that living in groups, “[may] increased probability of predator detection, … [create] greater confusion of a predator trying to focus on an individual prey, … [propitiate] a decreased probability of each individual being captured by predators, … and increased defense against predators” (Chapman 2000: 27). However, Janson (1998) indicated that the evaluation of predation should be done with caution due to the fact that presumed antipredatory behaviors (e. g. alarm calls, vigilance, living in larger groups) might be linked with other behaviors. For instance, he indicated that for some primate species it might be beneficial to live in small groups that are difficult for predators to detect. In addition, Hill & Dunbar (1998) suggested that predation risk is a more comprehensive parameter for evaluating predation on primates than predation rate. They argued that potentially the role of predation as selective pressure might be more important for primates when the risk of predation is perceived. In addition, they indicated that predator-prey relationship should be evaluated as the potentiality that a given primate species might be recovered from predatory events by adjusting its behavior. Recently, Miller (2002) added to the discussion the concept of predation vulnerability in understanding primate social organization. She defined vulnerability as the “qualitative measure of the probability that an individual will be the victim of a predator at any given moment” (Miller, 2002: 2). She indicated that this fact may play a major role in the foraging strategies and decision-making among primates. Miller (2002) suggested that predation vulnerability might be evaluated using three different variables. A biological variable, in which different characteristics that are “under genetic control” and expressed in the primate phenotype might be significant for a given antipredatory response (e. g. body size); a social variable such as differences in rank, group size and group composition; and an environmental variable such as the degree of predation vulnerability associated with foraging location and the quality of the cover or refuge available to primates. Humans as primate predators Isbell (1994) and Cheney & Wrangham (1987) briefly suggested that humans are the major predators on primates. Similarly, Boinski et al. (2000: 47) stated in their review, “primate predators are restricted to nonhuman predators because humans probably hunt most primates” (italics are mine). Thus, although the impact of humans as predators on primates has been noted, few researchers have focused on the role of human predators may have played in non-human primate social organization (see: Sponsel, 1997). Predation by humans has been under-emphasized in the theoretical discussions about predation on nonhuman primates. However, to hunt defined by the Oxford English Dictionary (Simpson & Weiner, 1989: 496) is “the act of chasing wild animals for the purpose of catching or killing them”; not less than another form of predation. Consequently, as indicated by Mittermeier (1987) and Chapman & Peres (2001), New World primates are highly threaten due to intense hunting or human predation. Nevertheless, humans had often been neglected in the literature on predation in primates (Sponsel 1997). In this paper I will examine primate prey-human predator relationship in the Neotropics. So, I address the following questions, a) Is there evidence that predators affect the B. Urbani structure of primate communities in Neotropical forests? b) How human predators differ from nonhuman predators in prey choice, hunting techniques and potential affect on primate social organization? b) Are humans primary agents that influence ecological changes such as local extinctions of primate populations? Methods Information of predation on Neotropical primates was compiled (see Appendix). Only observed predation cases on monkeys by direct sightings or from inspection of alimentary samples such as primate skeletal material in predator nests and primate remains in predator feces were included. For this purpose, a review of papers related to predation and hunting on primates in the Neotropics was systematically prepared from three bioanthropological -primatological- and ethnographical sources. First, a search was conducted of the major anthropological and biological databases such as Academic Search Elite, Anthropological Index, Anthropological Literature, Biological Abstracts (BIOSIS), Ecology Abstracts, JSTOR (including 35 ecological and anthropological journals dated from 1867 to 1999), PrimateLit and Zoological Record. Secondly, a bibliographic compilation was prepared from the reviews published by McDonald (1977), Coimbra-Filho & Mittermeier (1981), Beckerman & Sussenbach (1983), Mittermeier (1987), Mittermeier et al. (1988), Kinzey (1997), Sponsel (1997), Robinson & Redford (1994), Boinski et al. (2000), Cowlishaw & Dunbar (2000), Garber & Bicca-Marques (2002), Di Fiore (2002), Fuentes & Wolfe (2002), Urbani (2002) and Cormier (2003). Third, the four main primatological journals American Journal of Primatology (1981-2003), Folia Primatologica (1963-2003), International Journal of Primatology (1980-2003), Primates (19572003), and the ethnological Journal of Ethnobiology (1981-2003) were also examined. From the compiled references, the following information was obtained (see the Appendix): a) Non-Homo predator: corresponds with non- 91 human vertebrates that prey on Neotropical primates. b) Homo predator: refers only to Amerindian hunters of monkeys in the tropical forests. In this work only Amerindians groups were included, considering the assumption that are the human populations that preyed on monkeys inheriting long-term traditional hunting techniques and knowledge in the Neotropics (for Campesinos Latin American creoles-, see discussion). c) Prey: the targeted New World monkey genus obtained by non-Homo or Homo predators. Associated with this entry, in the cells of the Appendix, information on the numbers of observed predation cases, age/sex of the prey, and ranking of the prey is collected. In this sense, 1) Number of observed predation cases: refer to the quantity of the proved cases of predation on monkeys; 2) Age/Sex: age and sex of the prey; and 3) Ranking prey: only for the cases of Homo predators, refers to the rank for a given primate genus compared to all mammalian preys. d) Total of prey: the sum of all preys for a given predator and the number of prey in general. e) Observation period: the total amount of time of the primatological study or the time that the ethnographer spent in the Amerindian community in which the primate hunting events were observed. f ) Frequency of predation: relationship between the “Number of observed predation cases” per hour. For both, primatological and ethnographical data, in which the observation period was not reported by hour, I used the following conversion: 1 day = 10 hours, 1 month = 15 days, 1 year = 12 months. If the observation period was not explicitly reported, it is included as unknown. g) Locality: site in which the observation was done, including the region and the country. Results In Appendix, I summarizes the data archived from the bibliographical search on hunting and predation on Neotropical monkeys. A total of 89 entries were obtained, 33 (37.1% for non-Homo predators and 56 (62.9%) for Homo predators. For non-Homo predators, 51.5% the events were recorded in non-Amazonian forests (17/33, incl. the Guianas, Central American and subtropic 92 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys forests), and the other 48.5% (16/33) in the Amazonia. In the case of Homo predators, 69.6% (39/56) of the cases were in Amazonia while 30.4% (17/56) were in non-Amazonian forests. The frequency of predation was quite similar from 0.045/hour for non-Homo predators to 0.048/hour in Homo predators (Appendix). Among all non-Homo predators, avian predators appear to be the most common. Of 32 cases, harpy eagles (Harpia harpija, 21.2%, 7/33) and crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis, 12.1%, 4/33) are the most common predators. Among terrestrial non-Homo predators, jaguars (Panthera onca) accounted for 15.2% (5/33) of the observations. Ten other non-Homo predators accounted for 51.5% (17/33) of predatory events. For non-Homo predators it was not possible determine the sex/age classes of the monkeys preyed upon (69%, 29/42). However, for those predation cases in which the information was available, 21.4% (9/42) represent young animals (pooling together infants, juveniles and subadults) and the remaining 9.5% (4/42) were adults, while 69.1% were of unknown age. In the few cases in which the sex was observed, 9.5% (4/42) were males whereas 7.1% (3/42) females, and the rest 83.4% remained of unknown sex. For Homo predators, in all cases the specific sex/age classes were unknown. In addition, as indicated in the discussion (see below) 53.6% (30/56) of the entries of Homo predators explicitly stated that these human groups hunt at least one of the nonHomo predators listed in Appendix. Moreover, for Homo predators it is important to identify the ranking of monkey preferences among all mammal prey. It is interesting to note that among Appendix entries, monkeys are among the five most common preys (27.8%, 42/151; see Tab. 1), the rest 72.5% are for primates preferred over the six position of preference (15.9%, 24/151) or it is unknown the choice rank among Amerindian groups (56.3%, 85/151). I tested the prediction that Homo predators have higher proficiency obtaining New World monkeys than non-Homo predators. Proficiency was defined as the number of successful hunts of a given primate prey. Both, Homo predators and non-Homo predators were compared using G-test. The results indicate that humans are more proficient predators of New World primates (df= 12, p<0.01). Certainly, I am aware that some of the human data collected for this comparison might imply the use of shotguns. For that reason, in order to model the potential hunting without firearms, I reduced ten times the Homo predator subtotals and compared it with the non-Homo predator dataset without modification. Hence, after this subtraction and using the same statistical test, the results are still highly different. A ranking of New World monkeys arranged by the number of individuals hunted is presented in Tab. 2. The life history data, -mean body mass and interbirth interval-, were obtained from Kappeler & Pereira (2003). As showed in Tab. 2, Cebus is the most commonly hunted monkey for both Homo and non-Homo predators. For nonHomo predators, small and medium sized primates are selected more frequently. Among humans, large bodied genera such as Lagothrix, Ateles and Alouatta are the preferred prey. Therefore, for Homo predators, a larger primate body mass plays a major role in prey choice. Discussion Humans first arrived to lowland South America around 11,000 years ago (Amazonia: Roosevelt et al., 1996). The technology they used for hunting included primarily stone spear points as could be recovered from Pleistocene archaeological sites (Roosevelt et al., 1996). Thus, humans have likely played a fundamental role in hunting different animal prey since that time. Currently, based on this review of predation on New World non-human primates, it appears that Homo is the main predator of them when compared with non-Homo predators. In a study of protein requirements for Amazonian Amerindian B. Urbani population, it was suggested that a daily diet should have at least 40-50 g/day per capita of proteins where game meat and fish occupied an important place apart of plant proteins from sources such as mandioca (Gross, 1975, for discussion see: Beckerman, 1979). For obtaining Neotropical animal game, hunting practices are culturally based (Beckerman & Sussenbach, 1983; Sponsel, 1997; Lizot, 1979; Lizarralde, 2002). For example, Lizot (1979) indicated that food preferences and taboos among Yanomami groups determine the selection and consumption of particular food items, particularly key game animals. Also, cultural practices might influence the inhibition for eating some monkeys. Among the Desana of Amazonian Colombia, monkeys are prohibited meat for children, while howler monkeys are considered evil omens (ReichelDolmatoff, 1971). In addition, humans are dramatically decreasing the non-human predator populations. For instance, over-hunting in the Neotropics has created the so-called “empty forests,” were major mammals were removed from their natural habitats (Redford, 1992; Robinson, 1993). The result is that in some tropical areas, humans maybe are the only threat to feral monkey populations (Cowlishaw & Dunbar, 2000). This has been documented in terms of the decreasing 93 woolly monkey population in the Brazilian Amazon (Peres, 1991; see below). On the other hand, humans do not fit well in other proposed predatory predictions of predatorprimate prey interactions. In this sense, various anti-predatory behaviors such as mobbing, active defense (e. g. throwing branches) and alarm calls are not successful for the monkeys because they would be easily detected and killed by humans. For example, some Amerindian groups such as the Shirián of the upper Paragua River, Venezuela, performed monkey calls in order to wait for an acoustical response to locate their potential prey (Urbani, pers. obs.). On the other hand, in Mexico, the Lacandón people hear the roaring of the monkeys from a long distance to chase and hunt them (Baer & Merrifield, 1972). Moreover, other so-called anti-predatory behaviors like polyspecific associations and intragroup distance might aid human hunters in locating the primate groups. For instance, Balée (1985) reported that hunting howler monkeys by the Ka’apor in Brazil, take them an average of just 50 minutes from the moment they left from and returned to the settlement after the hunting party. This is the smallest amount of time used for hunting any mammalian game for this Amerindian group, the next nearest are collared peccaries that required in 94 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys average 240 minutes, so, almost five times more than howlers. The prediction that smaller-bodied size primates are more vulnerable to predators than larger bodied primates does not fit for human predators. It has been observed that large atelines are the preferred prey for many human groups, and are systematically selected as hunting targets (Mena et al., 2000; Alvard & Kaplan, 1991). Another prediction suggested that the vulnerability to predation might be higher in unfamiliar areas for the primates. Local human populations tend to know the monkeys home range, and in some cases hunters may predict the movements of primates populations through their knowledge of fruiting patterns of particular key tree species eaten by monkeys or identifying animal feces in the forest (e. g. the Makuna: Århem, 1976). On the other hand, the prediction that primates are more vulnerable in the canopy and forest edges may apply when being hunted by human predators. Based on interviews in the Venezuelan Guayana and eastern Venezuela, I received information from hunters (Amerindians and Creoles) indicating that hunting proficiency is higher when monkeys are exposed in the forest canopies rather than in dense tangles. They indicated that it is easier to hunt a spider monkey than tend to be found in the highest canopy than a capuchin monkey sometimes found in tangle understory forests strata or secondary forests. In this sense, Carneiro (1970) indicated that in Peruvian Amahuaca hunting, success decreases with higher dense foliage; however, he reported that this Amerindian group practiced tree climbing for hunting howler monkeys. The idea that predation is episodic must be re-evaluated when dealing with human hunters. Homo hunts primates on a regular basis and one hunting -predatory- episode by humans might result in the killing of many members of the monkey group. For example, Lizarralde (2002) reported the case of a single hunting day in which five Barí men returned to the village with 16 spider monkeys (Ateles hybridus). The consequences of living in group for avoiding predation as reviewed by Chapman (2000) must be revisited for human predators. Contrary to the prediction, living in a large group is a disadvantage, because monkeys may be more easily found by hunters. For instance, practically entire groups of woolly monkeys (130 individuals) and 11 howler monkeys were killed in one day by a Siona-Secoya hunting party composed by 286 persons in the Ecuadorian Amazon (Vickers, 1980). The idea that primate groups might create predator confusions and thereby decrease the feasibility that each individual may be preyed while increasing the defense against the predators, does not appears to function as a potential anti-predatory adaptation for human hunters. Hunters may kill the most of the whole group or just select particular individuals based on cultural preferences. In this sense, female primates may be selected to hunt in order to obtain offspring as pets. In the case of Ateles sp., females may be selected because they are considered more “tasty” than males (Waimiri-Atroari: Souza-Mazurek et al., 2000), more “tasty” than other monkey species such as Saimiri oerstedii (Guaymi: GonzálezKirchner & Sainz de la Maza, 1998), or even are considered “better” hunting games during the rainy season because this monkey species is fatter during this tree fruiting period (Matsigenka: Shepard, 2002). Boinski & Chapman (1995) provided new insights on potential directions for testing hypotheses of predation on primates. They argued that comparisons of predation rates with group size might represent a bias because of large intraspecific variability in primate group size. However, they suggest that other standards for comparisons like prey interbirth intervals might be more fruitful for understanding the effects of predation on primates. It is important to note that despite the low frequencies of predation for both predators, primates with longer interbirth intervals such as Ateles sp. and Lagothrix sp. are the preferred targets among human hunters (e. g. Yanomamö: Saffirio & Scaglion, 1982; Matsigenka: Shepard, 2002; Tabl. 1). This may result in low levels of primate population recovery and also local extinctions. Boinski & Chapman (1995: 2) state “on an evolutionary time scale, increased predation pressure may favor large groups, but on a shorter ecological time scale, high predation levels may decrease group size directly, simply through the death of animals.” In this regard, they indicated B. Urbani that G. B. Stanford studies of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) predation on red colobus monkeys (Procolobus badius) is an instructive example of the effect of predation on an ecological time scale. Chimpanzees hunting on red colobus (76 observed cases in four years) have reduced to almost the half the size of the monkey population that inhabit the chimpanzee groups’ range compared to the red colobus populations that live outside this range (e.g. Gombe site: Stanford, 1998 vs Kibale site: Struhsaker, 1975). In other words, in the field sites in which Pan density is higher, Procolobus density is lower (Stanford, 1998). A similar effect may be occurring in the Neotropics between human and some monkey populations. Since the Prehispanic period, Amerindians established a close relationship with non-human primates from cosmological believes to the thought of monkeys as food (Baker, 1992,; van Akkeren, 1998; Karadimas, 1999, Braakhuis, 1998, García del Cueto, 1989; Urbani & Gil, 2001; Cormier, 2003). In the present work only Amerindians groups were considered, assuming that are the human populations that first entered the New World while using long-term traditional hunting techniques. The predecessors of current Amerindian populations occupied the tropical Americas since circa 11,000 year ago to approximately 1,250-1,600 A. D., intensely using areas like lowland Panama and Brazil that have been historically considered “pristine” rainforests in the New World (Bush & Colinvaux, 1990; Colinvaux & Bush, 1991; Heckenberger et al., 2003). In addition, there is direct evidence from an archaeological site in northern Venezuela that reflected potential consumption or used for other purposes (e. g. pets) of red howler monkeys from at least 3,000 years B. P. (Urbani & Gil, 2001). In principle, these human groups may have influenced the distribution/survivorship of current primate populations, as might be the case of potential former populations of white-faced capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus) in the northern Mayan region (Baker, 1992). In addition, MacPhee & Horovitz (2002) suggested that probably the Pleistocene Antillean monkey Xenothrix mcgregori might be extinct due to human influence. So, intense hunting pressures over 10,000 years might directly influence local 95 extinctions of faunal populations and probably still unknown- contributing to shape the structure of current primate populations as might be tentatively inferred from the results. There is current evidence to support this idea. For instance, Souza-Mazurek et al. (2000 579; 591) indicated that among the Waimiri-Atroari in northern Brazil, “sex ratios of spider monkeys [Ateles paniscus] killed were heavily biased towards females indicating a stronger hunting pressure on those individuals.” Thus, it seems that potential sex-based differences in hunting selection are affecting the group structure of feral Neotropical primates groups; naturally more detailed studies to evaluate the effect of selective hunting on the primate population dynamic are needed. Moreover, Peres (1991) described local extinctions of woolly monkey (Lagothrix sp.) populations as a consequence of intense hunting in the Amazonia. He said that woolly monkey population density (number/km2) varied from 0 and 7 in hunted sites to 17 and 30 in nonhunted sites. In addition, Creole populations in Latin America intensively hunt primates for market networks that expand the limits of hunting from family consumption to hunting for commercial purposes (Mittermeier, 1987, for understanding Amazonian Caboblos -Brazilian Creoles- economy: Nugent, 1993). Bush meat is a preferred food source in the local marts. For example, Castro et al. (1975) found that in six months, in the popular market of Iquitos, Peru, were sold 1,700 Lagothrix sp., 1,396 Cebus sp., 557 Alouatta sp., 321 Pithecia sp. and 198 Ateles sp. (approximate calculation by B. U.). Thus, together with the Congo Basin in Africa where the bush meat crisis is aggressively threatening primate populations (Peterson, 2003), Amazonia appears to be the other geographical area critically threaten by hunting (Mittermeier, 1987; see Results). Then, to the question, why New World primates adopt the above indicated antipredatory behaviors even if they are not efficient against their main predator, Homo sapiens?. Two dimensions might be playing a role on it. First, humans have interacted with New World monkeys during just a short timeframe (~11,000 years) compared to the long-time period since primates had been found in the New World; the late Oligocene when Branisella boliviana 96 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys inhabited the central part of South America (Kay et al. 2002). On the other hand, human social practices and material culture (particularly weapons) take part in the equation of predation of Neotropical monkeys, being factors unique to Homo in the Neotropics. Nevertheless, extensive field research is needed to properly address this issue. Probably one of the best ways to inquiry about the relationship between Homo and New World primates, including in particular hunting -predatory- practices, is to look into new insights from ethnoprimatological perspectives on the conceptualization of monkeys by Amerindians; a research line that have been just initiated after Sponsel (1997) (in the Neotropics: Fleck et al., 1999; Cormier, 2002, 2003; Lizarralde, 2002; Shepard, 2002; Urbani & Gil, 2001). Many Amerindian groups have special tied relations with monkeys, and associated and classified them as “beings like humans” (e.g. Kalapalo: Basso, 1973). For instance, among the Mekranoti, a Tupi language Amerindian group related to the Kayapo group, indicated that other Amerindian groups used the word “Kaya-po” for referring them; the word “Kayapo” means the people that “resembled monkeys” (Werner, 1985: 173). Ethnoprimatological studies are fundamental for understanding the relationship between human and non-human primates. Moreover, these works will be essential for understanding the past and present interconnection of both sympatric primates and even more, to comprehend the still unknown but critical future of them. In addition, at the moment there are few systematic mentions describing the New Word primate reactions to human primates, and in principle there are practically no works specifically describing how humans have potentially affected social and grouping behaviors in Neotropical monkeys (for Old World primates: Coppinger & Maguire, 1980; Bshary, 2001; Tenaza, 1990; Tenaza & Tilson, 1985). This is an interesting area for future primatological research in the tropical Americas. Moreover, recent data on naïve behaviors and group composition of wild primates (for chimpanzees: Morgan & Sanz, 2003) may be fundamental for comparing with primate populations subjected to often human contact (including primatologists), in order to understand potential differences in primate social structure due to human presence or impact. Acknowledgments Many thanks to Loretta A. Cormier, Manuel Lizarralde, Leslie E. Sponsel and Robert S. Voss for sending me their publications for a previous bibliographic review (Urbani, 2002) that were useful for thinking in this work. To the UIUC library staff for make available valuable help in references searching. To Paul Garber and the anonymous referees for their critical suggestions. To Tania for her passion in the conservation of tropical rainforests and her enormous love. B. Urbani is granted by a Fulbright-OAS Scholarship. References Alvard M. 1993. Testing the “Ecologically noble savage” hypothesis: Interpecific prey choice by Piro hunters of Amazonian Perú. Hum. Ecol., 21: 355-387. Alvard M. 1995. Intraspecific prey choice by Amazonian hunters. Curr. Anthropol., 36: 789-818. Alvard M. 1995. Shotguns and sustainable hunting in the neotropics. Oryx, 29: 58-66. Alvard M. & Kaplan H. 1991. Procurement technology and prey mortality among indigenous neotropical hunters. In M.C. Stiner (ed): Human predators and prey mortality, pp. 79-104. Westview Press, Boulder. Århem K. 1976. Fishing and hunting among the Makuma: Economy, ideology and ecological adaptation in the northwest Amazon. Ann. Report of the Gotenborgs Etnografiska Museum, : 27-44. Baer P. & Merrifield W.R. 1972. Los Lacandones de México. Dos Estudios. Instituto Nacional Indigenista, Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City. Baker M. 1992. Capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus) and the Ancient Maya. Ancient Mesoam., 3: 219-228. Baleé W. 1985. Ka’apor ritual hunting. Hum. B. Urbani Ecol., 13: 485-510. Basso E.B. 1973. The Kalapalo Indians of Central Brazil. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York. Beckerman S. 1979. The abundance of protein in Amazonia: A reply to Gross. Am. Anthopol., 81: 53-56. Beckerman S. 1980. Fishing and hunting by the Bari in Colombia. Working Papers on South American Indians, 2: 68-109. Beckerman S. & Sussenbach T. 1983. A quantitative assessment of the dietary contribution of game species to the subsistence of South American Tropical forest tribal peoples. In J. Clutton-Brock & C. Crigson (eds): Animals and Archaeology. 1. Hunters and their preys, pp. 337-350. BAR International Series 163, Oxford. Berlin B. & Berlin E.A. 1983. Adaptation and ethnozoological classification: Theoretical implications of animal resources and diet of the Aguaruna and Huambisa. In R.B. Hames & W.T. Vickers (eds): Adaptive responses of native Amazonians, pp. 301-325. Academic Press, New York. Blomberg R. 1956. The naked Aucas. An account of the Indians of Ecuador.: George Allen & Unwin, London. Boinski S. & Chapman C.A. 1995. Predation on primates: Where are we and what’s next?. Evol. Anthropol., 4: 1-3. Boinski S.; Treves A. & Chapman C.A. 2000. A critical evaluation of the influence of predators on primates: Effect on group travel. In S. Boinski & P.A. Garber, (eds): On the Move. How and why animals travel in groups, pp. 43-72. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Braakhuis H.E.M. 1987. Artificers of the Days: Functions of the Howler Monkey Gods among the Mayas. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-, en Volkenkunde 143. Floris Publications, Dortrechs. Bshary R. 2001. Diana monkeys, Cercopithecus diana, adjust their anti-predator response behaviour to human hunting strategies. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol., 50: 251-256. Bush M.B. & Colinvaux P.A. 1991. A pollen record of a complete glaciar cycle from lowland Panama, J. Vegetation Sci., 1: 105-118. 97 Campos R. 1977. Producción de pesca y caza en una comunidad Shipibo en el río Pisqui. Amaz. Peruana, 1: 53-74. Carneiro R.L. 1970. Hunting and hunting magic among the Amachuaca of the Peruvian Montaña. Ethnology, 9: 331-341. Carpenter C.R. 1934. A field study of the behaviour and social relations of howling monkeys. Comp. Psychol. Monogr., 10: 1-168. Castro N., Revilla J. & Neville M. 1975. Carne de monte como una fuente de proteínas en Iquitos, con referencia especial a monos. Rev. Forestal del Perú. 5: 19-32. Reprinted in: N. Castro-Rodríguez (ed): La primatología en el Perú, pp. 17-35. 1990. Proyecto Peruano de Primatología, Lima. Chapman C.A. 1986. Determinants of group size in primates: The importance of travel cost. In S. Boinski & P.A. Garber (eds): On the Move. How and why animals travel in groups, pp. 2342. University of Chicago Press Chicago. Chapman C.A. & Peres C.A. 2001. Primate conservation in the New Millenium: The role of scientists. Evol. Anthropol., 10: 16-33. Chapman C. A. 2000. Boa constrictor predation and group response in white-faced Cebus monkeys. Biotropica, 18: 171-172. Cheney S. & Wragham R. 1987. Predation. In B.B. Smuts, R.M. Cheney, R.M. Seyfarth, R.W. Wrangham & T.T. Struhsaker (eds): Primate societies, pp. 227-239. University of Chicago Press, London. Chinchilla F. A. 1997. La dieta del jaguar (Panthera onca), el puma (Felis concolor), y el manigordo (Felis pardalis) (Carnivora: Felidae) en el Parque Nacional Corcovado, Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop., 45: 1223-1229. Coimbra-Fihlo A.F. & Mittermeier R.A. 1981. Ecology and Behavior of Neotropical Primates. Academia Brasileira de Ciências, Rio de Janeiro. Colinvaux P.A. & Bush M.B. 1991. The rainforest ecosystems as a resource for hunting and gathering. Am. Anthropol., 93: 153-160. Conzemius E. 1984. Estudio etnográfico sobre los indios Miskitos y Sumus de Honduras y Nicaragua. Libro Libre, San José. Coppinger R.P. & Maguire J.P. 1980. Cercopithecus aethiops of St. Kitts: A population estimate based on human 98 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys predation. Caribb. J. Sci., 15: 1-7. Cormier L.A. 2002. Monkey as food, monkey as child: Guajá symbolic cannibalism. In A. Fuentes & L.D. Wolfe (eds): Primates face to face: Conservation implications of human and nonhuman primate interconnections, pp. 6384. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Cormier L.A. 2003. Kinship with monkeys. The Guajá foragers of Eastern Amazonia. Columbia University Press, New York. Côrrea H.K.M & Coutinho P.E.G. 1997. Fatal attack of a pit viper, Bothrops jararaca, on an infant buffy-tufted ear marmoset (Callithrix aurita). Primates, 38: 215-217. Cowlishaw G. & Dunbar R. 2000. Primate Conservation Biology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Crocket J.C. 1985. Vital souls. Bororo cosmology, natural symbolism, and shamanism. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. Cuarón A.D. 1997. Conspecific aggression and predation: Costs for a solitary mantled howler monkey. Folia Primatol., 68: 100-105. Descola, P. 1996. The spears of twilinght. Life and death in the Amazon jungle. The New Press, New York. Di Fiore A. 2002. Predator sensitive foraging in ateline primates. In L.E. Miller, (ed): Eat or be Eaten, pp. 242-268. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Eakin E., Lauriault E. & Boonstra H. 1980. Bosquejo etnográfico de los Shipibo-Conibo del Ucayali.: Ignacio Prado Pastor Ediciones, Lima. Eason P. 1989. Harpy eagle attempts predation on adult howler monkey. Condor, 91: 469-470. Emmons L.J. 1987. Comparative feeding ecology of felids in a Neotropical rainforest. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol., 20, 271-283. Ferrari S.F., Pereira W., Santos R.R. & Viega L.M. 2002. Ataque fatal de uma jibóia (Boa sp.) em um cuixú (Chiropotes satanas utahicki). Livro de Resumos do X Congresso Brasileiro de Primatologia: Amazonia, a última fronteira, 66. Fleck D.W., Voss R.S. & Patton J.L. 1999. Biological basis of saki (Pithecia) folk species recognized by the Matses Indians of Amazonian Peru. Int.. J. Primatol., 20: 10051028. Fowler J.M. & Cope J.B. 1964. Notes on the harpy eagle in British Guiana. The Auk, 81: 257-273. Fuentes A. & Wolfe L. D. (eds) 2002. Primates face to face: Conservation implications of human and nonhuman primate interconnections. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Galef B.G.Jr., Mittermeier R.A. & Bailey R.C. 1976. Predation by the tayra (Eira barbara). J. Mammal., 57: 760-761. Garber P.A. & Bicca-Marques J.C. 2002. Evidence of predator sensitive foraging and traveling in single- and mixed-species tamarin troops. In L.E. Miller (ed): Eat or be Eaten., pp. 138153. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. García del Cueto H. 1989. Acerca de la connotación simbólico-ritual del mono en la sociedad prehispánica (Altiplano Central). In A. Estrada, R. López-Wilchis & R. CoatesEstrada (eds): Primatología en México: Comportamiento, ecología, aprovechamiento y conservación de primates, pp. 144-159. Universidad Autónoma MetropolitanaIztapalapa, Mexico City. Gilbert K.A. 2000. Attempted predation on a white-faced saki in the Central Amazon. Neotrop. Primates, 8: 103-104. Goldizen A.W. 1987. Tamarins and marmosets: Communal care of offspring. In B.B. Smutts, R.M. Cheney, R.M. Seyfarth, R.W. Wrangham & T.T. Struhsaker (eds): Primate societies, pp. 34-43. Chicago University Press, London. González-Kirchner J.P. & Sainz de la Maza M. 1998. Primates hunting by Guaymi Amerindians in Costa Rica. Human Evol., 13: 15-19. Gregor T. 1977. Mehinaku. The drama of daily life in a Brazilian Indian village.: University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Gross D. 1975. Protein capture and cultural development in the Amazon basin. Am. Anthopol., 77: 526-549. Hames R.B. 1979. A comparison of the efficiencies of the shotgun and the bow in neotropical forest hunting. Human Ecol., 7: 219-252. Harner M. J. 1972. The Jivaro: people of the Sacred Waterfalls. Doubleday-Natural History, New York. Heckenberger M.J., Kuikuro A., Kuikuro U.T., B. Urbani Russell J.C., Schmidt M., Fausto C. & Franchetto B. 2003. Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest or Cultural Parkland?. Science, 301: 1710-1714. Heymann E.W. 1987. A field observation of predation on a moustached tamarin (Saguinus mystax) by an anaconda. Int. J. Primatol., 8: 193-195. Hill K. & Padwe J. 2000. Sustainability of Ache hunting in the Mbaracayu Reserve, Paraguay. In J.G. Robinson & E.L. Bennett (eds): Hunting for sustainability in tropical forests, pp. 79-105. Columbia University Press, New York. Hill R.A. & Dunbar R.L.M. 1998. An evaluation of the roles of predation rate and predation risk as selective pressures on primate grouping behaviour. Behaviour, 135: 411-430. Isbell L.A. 1994. Predation on primates: Ecological patterns and evolutionary consequences. Evol. Anthropol., 3: 61-71. Izawa K. 1978. A field study of the ecology and behavior of the black-mantled tamarin (Saguinus nigricollis). Primates, 19: 241-274. Izor R.J. 1985. Sloths and other mammalians prey of the harpy eagle. In G. G. Montgomery, (ed): The evolution and ecology of armadillos, sloths and vermilinguas, pp. 343-346. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington. Janson C.H. 1998. Testing the predation hypothesis for vertebrate sociality: Prospects and pitfalls. Behaviour, 135: 389-410. Julliot C. 1994. Predation of a young spider monkey (Ateles paniscus) by a crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis). Folia Primatol., 63: 75-77. Kappeler P.M. & Pereira M.E. 2003. Appendix. A primate life history database. In P.M. Kappeler & M.E. Pereira (eds): Primate life histories and socioecology, pp. 313-330. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Karadimas D. 1999. La constellation des quatre signes. Interprétation ethnoarchéoastronomique des motifs de “El Carchi-Capulí” (Colombie, Équator). J. Soc. Américanistes, 85: 115-145. Kay R.F., Williams B.A. & Anaya F. 2002. The adaptation of Branisella boliviana, the earliest South American monkey. In Plavcan J.M., Kay R.F., Jungers W.L. & C.P. van Schaik, (eds): Reconstructing behavior in the primate fossil record, pp. 339-370. Kluwer 99 Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. Kensinger K.M., Rabineau, P., Tanner, H., Ferguson, S.G. & Dawson A. 1975. The Cashinahua of Eastern Peru. Studies in Anthropology and Material Culture, Vol. 1. The Haffereffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University Press, Providence. Kinzey W.G. (ed) 1997. New World Primates: Ecology, evolution and behavior. Aldine de Gruyter, New York. Kracke W.H. 1978. Force and persuasion. Leadership in an Amazonian Society. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Lizarralde M. 2002. Ethnoecology of monkeys among the Barí of Venezuela: perception, use and conservation. In A. Fuentes & L.D. Wolfe (eds): Primates face to face: Conservation implications of human and nonhuman primate interconnections, pp. 85-100. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Lizot J. 1979. On food taboos and Amazon cultural ecology. Curr. Anthropol., 20: 150-151. MacPhee, G. & I. Horovitz. 2002. Extinct Quaternary platyrrhines of the greater Antilles and Brazil. In W.C. Hartwig (ed): The primate fossil record, pp. 189-200. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Maybury-Lewis D. 1967. Akwê-Shavante society. Clarendon Press, Oxford. McDonald D.R. 1977. Food taboos: A primitive environmental protection agency (South America). Anthropos, 72: 735-748. Meggers B.J. 1971. Amazonia. Man and culture in a counterfeit paradise. Aldine-Atherton, New York. Mena V.P., Stallings J.R., Regalado B.J. & Cueva L.R. 2000. The sustainability of current hunting practices by the Huaorani. In J.G. Robinson & E.L. Bennett (ed): Hunting for sustainability in tropical forests, pp. 57-78. Columbia University Press, New York. Merriam J.C. 1998 - Community wildlife management by Mayangna Indians in the Bosawas Reserve, Nicaragua. M. S. thesis, Idaho State University. Miller L.E. 2002. An introduction to predator sensitive foraging. In L. E. Miller (ed): Eat or be Eaten, pp. 1-20. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Milton K. 1991. Comparative aspects of diet in 100 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys Amazonian forest-dwellers. In: A. Whiten & E.M. Widdowson (eds): Foraging strategies and natural diet of monkeys, apes and humans, pp. 93-103. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Mitchell C.L., Boinski, S. & van Schaik, C.P. 1991. Competitive regimes and female bonding in two species of squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi and S. sciureus). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol., 28: 55-60. Mittermeier R.A. 1987. Effects of hunting on rain forest primates. In C.W. Marsh & R.A. Mittermeier (ed): Primate conservation in the tropical rain forest, pp. 109-146. Alan R. Liss, New York. Mittermeier R.A. 1991. Hunting and its effect on wild primates populations in Suriname. In J.G. Robinson & K.H. Redford (eds): Neotropical wildlife use and conservation, pp. 93-107. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Mittermeier R.A., Rylands A.B., Coimbra-Fihlo, A.F. & da Fonseca, G.A.B. 1988. Ecology and behavior of Neotropical Primates. World Wildlife Fund, Washington. Montgomery E.I. 1970. With the Shiriana in Brazil.: Kendall/Hunt Publishing, Dubuque. Morgan D. & Sanz C. 2003. Naïve encounters with chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo. Int. J. Primatol., 24: 369381. Moynihan M. 1970. Some behavior patterns of Platyrrhine monkeys, II. Saguinus geoffroyi and some other tamarins. Smithsonian Contrib. Zool., 29: 1-77. Murphy R.F. & Quain B. 1966. The Trumaí Indians of Central Brazil. Monographs of the American Ethnological Society, 24. University of Washington Press, Seattle. Nimuendajú C. 1946. The Eastern Timbira. University of California Press, Berkeley. Nugent S. 1993. Amazonian Caboclo society: An essay on invisibility and peasant economy. Berg Publishers, Oxford. Olmos F. 1994. Jaguar predation on muriqui, Brachyteles arachnoids. Neotrop. Primates, 2: 16. Oversluijs-Vasquez M.R. & Heymann E.W. 2001. Crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis) predation on infant tamarins (Saguinus mystax and Saguinus fuscicollis, Callitrichinae). Folia Primatol., 72: 301-303. Peres C.A. 1990. A harpy eagle successfully captures an adult male red howler monkey. Wilson Bull., 102: 560-561. Peres C.A. 1991. Humboldt’s woolly monkeys decimated by hunting in Amazonia. Oryx 25: 89-95. Peterson, D. 2003. Eating Apes. University of California Press, Berkeley. Redford K.H. 1992. The empty forests. BioScience, 42: 412-422. Reichel-Dolmatoff G. 1989. Amazonian Cosmos. The sexual and religious symbolism of the Tukano Indians. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Rettig N.L. 1978. Breeding behavior of the harpy eagle, Harpia harpyja. The Auk, 95: 629-643. Reverte J.M. 1967. Los indios Teribes de Panamá. Talleres de la Estrella de Panamá, Panama City. Robinson J.G. 1993. The limits to caring: Sustainable living and the loss of biodiversity. Conserv. Biol., 7: 20-28. Robinson J.G. & Redford K.H. 1994. Measuring the sustainability of hunting in tropical forests. Oryx, 28: 249-256. Roosevelt A.C., Lima da Costa M., Lopes Machado C., Michab M., Mercier N., Valladas H., Feathers J., Barnett W., Imazio da Silveira M., Henderson A., Sliva J., Chernoff B., Reese D.S., Holman J.A., Toth N. & Schick K. 1996. Paleoindian cave dwellers in the Amazon: The peopling of the Americas. Science, 272: 373-384. Ross E.B. 1978. Food taboos, diet, and hunting strategy: The adaptation to animals in Amazon cultural ecology. Curr. Anthropol., 19: 1-36. Saffirio G. & Scaglion R. 1982. Hunting efficiency in acculturated Yanomama villages. J. Anthropol. Res., 38: 315-328. Schaller G.B. 1983. Mammals and their biomass on a Brazilian Ranch. Arq. Zool. (São Paulo), 31: 1-36. Seeger A. 1981. Nature and society in Central Brazil. The Suya Indians of Mato Grosso. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Setz E.Z.F. 1991. Animals in the Nambiquara diet: methods of collection and processing. J. Ethnobiol., 11: 1-22. Shepard G.Jr. 2002. Primates in Matsigenka B. Urbani subsistence and worldview. In A. Fuentes & L. D. Wolfe (eds): Primates face to face: Conservation implications of human and nonhuman primate interconnections, pp. 101136. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Sherman P.T. 1991. Harpy eagle predation on a red howler monkey. Folia Primatol., 56: 53-56. Simpson, J.A. & Weiner E.S.C. 1989. The Oxford English Dictionary. Volume VII. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Siskind J. 1973. To hunt in the morning. Oxford University Press, New York. Souza-Mazurek R., Pedrinho T., Feliciano X., Hilario W., Geroncio S. & Marcelo E. 2000. Subsistence hunting among the Waimiri Atroari Indians in central Amazonia, Brazil. Biodivers. Conserv., 9: 579-596. Sponsel L.E. 1997. The human niche in Amazonia: Explorations in ethnoprimatology. In W.G. Kinzey (ed): New World primates. Ecology, evolution, and behavior, pp. 143-165. Aldine de Gruyter, New York. Stanford, G.B. 1998. Chimpanzee and red colobus. The ecology of predator and prey. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Stafford B.J. & Murad-Ferreira, F. 1995. Predation attempts on Callitrichids in the Atlantic coastal rain forest of Brazil. Folia Primatol., 65: 229-233 Struhsaker T.T. 1975. The red colobus monkey. Chicago University Press, Chicago. Tenaza R.R. 1990. Effects of human predation on behavior of pig-tailed langurs in the Mentawai Islands. Am. J. Primatol., 20: 237-238. Tenaza R.R, Tilson R.L. 1985. Human predation and Kloss’s gibbon (Hylobates klossii) sleeping trees in Siberut Island, Indonesia. Am. J. Primatol., 8: 299-308. Terborgh J. 1983. Five New World Primates. Princeton University Press, Princeton. Thompson, J.E. 1930. Ethnology of the Mayas of southern and central British Honduras. Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 274. Anthropological series, 27: 27-213. Townsend W.R. 2000. The sustainability of subsistence hunting by the Siriono Indians of 101 Bolivia. In J.G. Robinson & E.L. Bennett (eds): Hunting for sustainability in tropical forests pp. 267-281. Columbia University Press, New York. Tsukahara T. & Nishida T. 1990. The first evidence for predation by lions on wild chimpanzees. XIIIth Congress of the International Primatological Society Abstracts (Nagoya), pp. 82 Urbani B. 2002. Neotropical ethnoprimatology: An annotated bibliography. Neotrop. Primates, 10: 24-26. Urbani B. & Gil E. 2001. Consideraciones sobre restos de primates de un yacimiento arqueológico del Oriente de Venezuela (América del Sur), Cueva del Guácharo, estado Monagas. Munibe, 53: 135-142. van Akkeren R. 1998. The monkey and the black heart. Polar North in Ancient Mesoamerica. In A.L. Izquierdo (ed): Memorias del Tercer Congreso Internacional de Mayistas, pp. 165185. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. van Schaik C.P., Horstermann M. 1994. Predation risk and the number of adult males in a primate group: A comparative test. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol., 35: 261-272. Vickers W. 1980. An analysis of Amazonian hunting yields as a function of settlement age. Working Papers on South American Indians, 2: 7-30. Viveiros de Castro E. 1992. From the enemies point of view. Humanity and divinity in an Amazonian society. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. von Graeve B. 1989. The Pacaa Nova. Clash of cultures on the Brazilian border. Broadview Press, Petesburgh. Wagley C. 1977. Welcome of tears. The Tapirapé Indians of Central Brazil. Oxford University Press, New York. Wagley C. &, Galvão E. 1949. The Tenetehara Indians of Brazil. A culture in transition. Columbia University Press, New York. Werner D. 1985. Amazon Journey. An anthropologist’s year among Brazil’s Mekranoti Indians. Simon and Schuster, New York. Appendix - Comparison of predation on New World primates. 102 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys Appendix - (continued). B. Urbani 103 Appendix - (continued). 104 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys Appendix - (continued). B. Urbani 105 Appendix - (continued). 106 Predation on Neotropical Monkeys Appendix - (continued). B. Urbani 107 108 Appendix - (continued). Predation on Neotropical Monkeys Appendix - (continued). B. Urbani 109 110