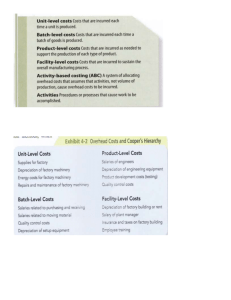

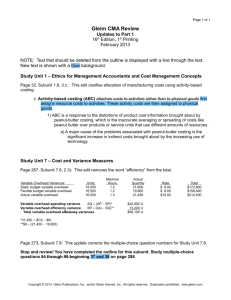

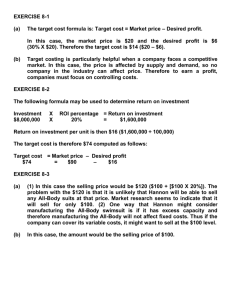

Activity-Based Costing and Quality Management

advertisement