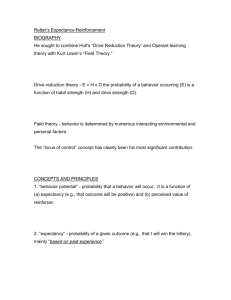

Generalized Expectancies for Internal Versus External

advertisement