Think Literacy

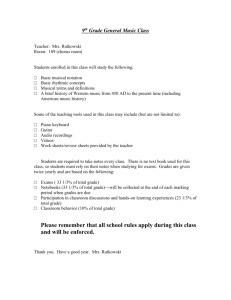

advertisement