Decision - the British Columbia Utilities Commission

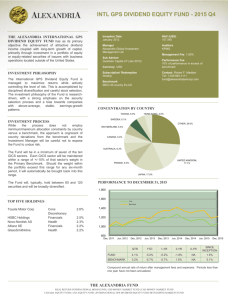

advertisement