Submission - Ontario Energy Board

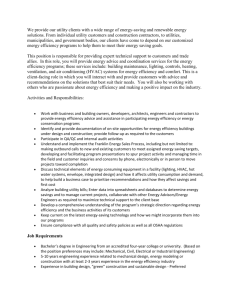

advertisement