A Reward, Recognition, and Appraisal System for Future

advertisement

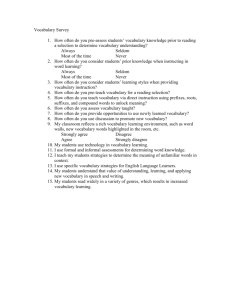

Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 A Reward, Recognition, and Appraisal System for Future Competitiveness: A UK Survey of Best Practices Research Paper: RP-ECBPM/0033 By Professor M. Zairi, Dr. Yasar F. Jarrar & Elaine Aspinwall Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 1 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 A Reward, Recognition, and Appraisal System for Future Competitiveness: A UK Survey of Best Practices Yasar F. Jarrar 1, Elaine Aspinwall 2, Mohamed Zairi 3 1 Dr. Yasar F. Jarrar European Centre for Total Quality Management University of Bradford, Emm Lane, Bradford, BD9 4JL E-mail – y.a.s.a.r.jarrar@bradford.ac.uk 2 Mrs. Elaine Aspinwall University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT E-mail – e.aspinwall@bham.ac.uk 3 Professor Mohamed Zairi European Centre for Total Quality Management University of Bradford, Emm Lane, Bradford, BD9 4JL E-mail – mzairi@bradford.ac.uk Keywords Human resource management, survey, best practices, rewards, recognition, appraisal Abstract Managing business productivity has essentially become synonymous with managing change effectively. To manage change, companies must not only determine what to do and how to do it, they also need to be concerned with how employees will react to it (Cooper and Markus 1995)(Reger et al., 1994). It is becoming increasingly clear that the engine for organisational development is not analysts, but managers and people who do the work. Without altering human knowledge, skills, and behaviour, change in technology, processes, and structures is unlikely to yield long-term benefits. In this respect, the role of Human Resource Management (HRM) is moving from the traditional ‘control and command’ approach to a more strategic one (Oram and Wellins 1995)(Cane 1996). Various studies have highlighted “reward and recognition” systems as one of its major critical success elements (Agarwal et al., 1998). Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 2 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 This paper is based on outcomes from a study which was aimed at identifying best practices in reward, recognition and appraisal systems by analysing the experiences of pioneering organisations and validating the findings through a survey of leading UK organisations. 1. Introduction Managing business productivity has essentially become synonymous with managing change effectively. To manage change, companies must not only determine what to do and how to do it, they need to also be concerned with how employees will react to it. Organisations are bound to continue having trouble implementing change until they learn that people resist not change per se, but the way they are treated in the change process and the roles they play in the effort (Cooper and Markus, 1995)(Reger,1994). When companies make changes, employees experience transitions during which they adapt. While changes can be implemented relatively quickly, transitions often require a longer time frame (Decker and Belohlav, 1998). It is becoming increasingly clear that the engine for organisational development is not analysts, but managers and people who do the work. Without altering human knowledge, skill, and behaviour, change in technology, processes, and structures is unlikely to yield long-term benefits. In fact, ‘human development’ is a viable alternative to ‘traditional’ organisational development as a strategy for bringing about dramatic performance improvements. ‘The key to our long sustainable success was, and is, people. Rained, equipped, properly rewarded and recognised’ TNT Director, 1999. The new world of work is introducing flexible working hours, knowledge workers, working from home, etc. So while these patterns emerge, organisations must change the way they deal with their people to achieve maximum benefit. It is firmly believed that the success of an organisation lies more in its intellectual and systems capabilities than in physical assets. Without altering human knowledge, skill, and behaviour, change in technology, processes, and structures is unlikely to yield long-term benefits. The “process” and “IT” aspects of any organisation are continuously changing, subject to daily improvements, and easily replicated by competitors. It is estimated (Slater, 1995) that competitors secure detailed information on 70% of new products within one year of introduction, and that 60 to 70 % of all ‘process learning’ is eventually acquired by competitors. In fact, ‘human development’ is a viable alternative to ‘traditional’ organisational Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 3 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 development as a strategy for bringing about dramatic performance improvements. Thus, the model suggests that the only source of competitive advantage is the organisation’s people (committed, educated, and flexible). The capacity to manage human intellect - and to convert it into useful products and services - is fast becoming the executive skill of the age. The main theory being proposed here is that an organisation’s only path to ‘sustainable’ performance excellence is by maximising its people’s potential. New processes, IT, strategies, products and services will come and go as we have learnt over the years. Only creative, innovative, change oriented people can carry the organisation to a leadership position, and keep it there. 2. Study Objectives and Methodology The study presented in this paper is part of a larger research project aimed at identifying best practice of people and knowledge management for future competitiveness. The part being discussed in this paper had the main objective of identifying the best practices for rewarding and appraising the organisation’s people. To achieve these objectives, the study identified what was presented by the literature and published case studies as reward and appraisal best practices (Quinn, 1996)(Lee, 1996)(Littlefield1996)(Imberman, 1996)(Van de Vliet, 1997)(Brown, 1997)(Agarwal, at al., 1998)(Kerr, 1998)(Hale, 1998). These have then been reproduced in a generic format and structured in a questionnaires to assess the applicability and the view points of experienced practitioners toward them. The survey focused on targeting leading organisations and practitioners who are well known for the performance, to see how many ‘subscribed’ to the ideas proposed, thus providing further proof whether these ideas were the right approach to achieving performance excellence in the future. The questionnaire was designed and piloted to assess: time required to complete the questionnaire, simplicity, clear language (no business jargon or academic purism), clarity of instructions, comprehensiveness, and item sequence. The pilot sample included KPMG, University of Birmingham, Rover Group, Grimley, Andersen Consulting, and United Industries Limited. Once the final questionnaire version was available, the survey sample was selected. For the purpose of the study, the only criteria for sample selection was that organisations taking part had to be leaders in their field (the assumption was that leading organisations would provide the best Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 4 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 insights into best practices). The sources used to select the sample were case studies analysed in the literature, market knowledge, and quality award winners (e.g. EQA, MBNQA). A further selection process involved the individuals to be contacted. Where possible, the contact was the most senior manager in the organisation. The sample size was based on the participants of the study, i.e. an available resource rather than ensuring a sufficient size to emulate the population (this was not an objective). Like most decisions relating to research design, there is rarely a definitive sample size for any given study (Wunsch, 1986)(Fowler, 1993). A decision was taken to send out 300 questionnaires for the UK/USA study (hoping for a response rate of at least 20%. In total 75 companies took part from both the UK/USA with a response rate of 25%. Organisations that responded included Ove Arup Partnership, Cap Gemini, BT PLC, Oracle Corporation UK Ltd, 3COM (UK) Limited, Nortel Ltd, Kodak Ltd, DHL International (UK) Ltd, IBM UK Ltd., Royal Mail, Skandia Life, Xerox (UK) Ltd., Dana Commercial Credit Corporation, Trident Precision Manufacturing Inc., Globe Metallurgical Inc., Rolls Royce Aero Engines Ltd., Honda Motor Europe Ltd., among others. The organisations that responded came from the manufacturing (44.3%) and services (55.7%) sectors. The manufacturing sector included industrial and consumer goods manufacturers like automotive, auto parts, medical products, and office equipment. The service sector included business consulting, banking and financial services, food retail, advertising, IT consulting, courier, insurance, and education. All the respondents were experienced practitioners at senior levels in their organisation. Figures 1 shows a breakdown of the respondents by job function. Senior Management (CEO, MD, GM) Human Resource Management Head Quality Head Process / Operations 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Figure 1 - Breakdown of respondents by job functions 3. Study Findings Initially, the study participants were presented with several statement to assess the perceived importance of people and people management for organisational competitiveness. Participants were requested to show Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 5 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 how strongly they agreed with these statements on a 5-point Likert scale. In focusing on reward, recognition and appraisal systems, the participants were presented with several proposed best practices and were asked to assess their applicability and criticality for a successful people management system. 3.1 The Future of People Management (PM) A PM strategy for the future must start by answering the question ‘what sort of people will the organisation need?’ Once answered, the strategy to meet these needs can be established. The study results (Table 1) reveal the people attributes that organisations seek for future success. The results clearly indicate the importance of customer orientation and team skills, which have both become almost ‘standard’ requirements this decade. However, the survey does reveal that participants view attributes like being creative, flexible, and ambitious as far more important than being loyal to the company or compliant with policies. Similar results were revealed in a study performed by Harvard Business Review (Carnall, 1997), which compared required attributes from organisational employees (managers and others) in 1980’s and 1990’s. Figure 2 shows a summary of this study’s results. Attribute Customer oriented Co-operative (Team players) Flexible Creative Multiskilled Ambitious (Stretch goals) Self disciplined Loyal Compliant with policies % of study participants who strongly agree / agree 97 85.6 70.4 67.2 60.6 50.8 37.7 13.1 13.1 Table 1 - Employee attributes required for future performance excellence – study results All of these findings suggest that, although the statement so often articulated ‘the most important resource of this business is its people’ is increasingly meaningful, not merely as rhetoric but also in practice, the type of people that today’s organisations require, and are dealing with, today and tomorrow, are different from a decade ago. Thus, if organisations depend more and more on fewer people and if the loyalty of those people can no longer be assumed but rather must be earned and retained, then clearly they need to be concerned about how they utilise them, develop them and resource them and about the opportunities for rewards, promotion and success which they provide (Carnall, 1997). This is a shift of focus that evolved in the 90’s. It occurred because within today’s turbulent market place, the people (employees) themselves, their Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 6 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 expectations, and the organisation’s expectations of them have all changed. As a consequence, the old ‘traditional’, personnel and HRM tools and methods also need rejuvenating and are not capable of achieving the required future success. 70 60 Well educated Creative Ambitious Loyalty 50 40 30 20 10 0 1 2 Figure 2 - Changes in required attributes in employees (1980-1990) (Carnall, 1997). In the following sections, best practices for PM are proposed, assessed, and tested. However, it must be stressed that these proposals form a guiding framework only, as there is no single right way to solve human resource issues. What works in one organisation may be quite inappropriate for another. The complexity of managing people matches the complexity of human nature. 3.2 Reward, recognition, and Appraisal Best Practices For the purpose of the study, the practices proposed were considered validated as ‘best practices’ if 75% of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement and none ‘strongly disagreed’. The reasoning behind this choice of 75% point was that the concepts being proposed by the framework were exploratory in nature. They were practices suggested for future success, and have only been applied by pioneers (best performers in their fields), or suggested in the literature to date. Thus they would be new to most organisations questioned, and would present a change from the norm. If 75% agreed that they are ‘best practices’ and none disagreed, then it could be concluded that most of the remaining respondents do not hold any strong opinions (for or against) probably due of lack of experience with the idea. This would be sufficient grounds upon which to conclude that such a practice would have positive outcomes when properly applied in an organisation (i.e. best practice). A literature review on related studies (Loomba and Jonanessen, 1997) (APQC, 1999)(APQC, 1996)(APQC, 1997)(DTI, 1995)(Ashton, 1998) has revealed similar approaches, and demonstrated that there is no clear cut-off point. In determining the best practices in Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 7 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 their studies, The Industrial Society (1996), and the American Productivity and Quality Centre APQC, 1999)(APQC, 1996)(DTI, 1995)APQC, 1997) defined them as practices that received the highest approval from study participants. 4. Reward and recognition A reward system can be described as ‘any conscious intervention or series of interventions within an organisation aimed at encouraging or reinforcing required behaviours, or which compensate people for taking particular actions.’ (Oram and Wellins, 1995). Reward strategies are not only about money, they are about both tangible and intangible forms of reward. Financial rewards include short term incentives made up from salary and bonuses while long term incentives include profit sharing, share ownership and stock options. These rewards are not commonly regarded as motivational in the long term but when they are not perceived to be ‘fair’, they can become demotivating agents (Cane, 1996). Employee benefits include insurance cover, pension schemes and sick pay, while fringe benefits include cars, holidays, and company discounts. Non-financial benefits are more complex and include motivational aspects that are largely intrinsic (derived from the job itself) and are mainly self generated in that people seek the type of work that satisfies them, and can be enhanced by management through giving greater responsibility, development, job design, policies and practices (Cane, 1996). Reward used to be generally about paying people the least that an organisation could get away with. Now that organisations are looking for employees to be involved and to continue innovating, reward systems need rejuvenating (Littlefield, 1996). In such a competitive knowledge based environment, the organisation’s best chances for attracting and retaining the best people lie in its ability to deliver the best ‘value’ compensation package to them. Compensation packages must be tailored to individual needs and cater for all intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. In an effort to propose the best practices for a reward and recognition system, the first aspect of designing such a system is to involve the employees that it affects in its design. Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 8 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 Proposed best practice - Employees must participate in designing the reward system Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree of disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 20 40 60 80 Figure 3 - Employee participation in reward system design – study results A 77.4% approval amongst study participants rates this as a best practice. Thus, each organisation should consider its culture carefully and consult staff before embarking on a new reward strategy. However, the method of participation though is very crucial and not enough work as been done to tackle this issue. Clearly, it varies form one organisation to the other, and is very organisational culture dependent. Cases revealed that some organisations form committees of employees who design the whole system subject to management negotiation and approval. Others design the system and solicit employee feedback. Proposed best practice – Pay-out plans should be subject to improvement as market and product strategies change Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree of disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 20 40 60 80 100 Figure 4 - Market based reward strategies – study results The agreement shown in Figure 4 confirmed this as a best practice, and a crucial one. Reward systems should be subject to monitoring and improvement with changing market conditions, for better or worse. This is the only way that both employees and management would view it as ‘fair’. Saturn Corporation (Cane, 1996) devised a Risk and Reward programme made up of base pay, risk pay, and reward pay. Base pay is lower than market rate, that is the risk part, but team members can, with reward pay, earn considerably more than market rate. Because employees are prepared to take the risk in return for a genuine share of the profitability of the organisation, both sides feel it is fair. The secret of success in such an adaptive system is Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 9 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 true and open communication. Galaxo-Wellcome (Littlefield, 1996) is moving towards a reward system that, while taking market rates into account, pays people according to their level of competence. The firm is aiming to introduce a system where about 85% of pay is fixed, leaving 15% for a bonus based on output. Experts (Willetts, 1999) predict that compensation, in the future, will be comprised of variable parts, for example team bonuses, that may total 40% of income. As for the detailed design of the reward system, there are several successful approaches being used by today’s successful organisations (Oram and Wellins, 1995), and the model suggested a combination as follows: 1. Pay for performance 50.4% of the study participants agreed with this concept (Figure 5), which is a good sign that awareness of this theory is spreading. Druker (1992) and Kanter (1989) argued that the nature of new management practices and the role of knowledge workers means managers and knowledge workers may insist on a growing share of corporate profits. Statement - Managers and knowledge workers in the future will insist on a growing share of corporate profits Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree of disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Figure 5 Employee demands on corporate gain – study results With the overall trends of increase in knowledge workers (Chase, 1997), it is believed that the above statement is an inevitable result. Employees rationalise that if a company cannot afford to treat them as family anymore, then at least it ought to treat them as business partners. Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 10 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 Proposed best practice - Organisational profit must be shared between the company and employees. Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree of disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 20 40 60 80 100 Figure 6 Sharing organisational profit with employees – study results 80.5% of the study participants agreed thus validating this best practice. The idea of sharing corporate profit is the characterisation of the new employee-organisation relationship discussed earlier. Dana Mead Corporation (Quinn, 1996) believe that what motivates today is more shares in corporate gains. Such programmes are on the rise and are sound business investments and are self funding. However, there are many levels to this profit sharing and each organisation must tailor the system to its culture and environment. Some organisations have seasonal variations and to this date, many employees agree to share profits but are reluctant to share losses. A massive cultural change is required. Rank Xerox (Oram and Wellins, 1995) have a system of rewards linked to business performance, with a growing proportion of variable pay. Pay is increasingly linked to achievement of corporate priorities, with a significant bonus for customer satisfaction paid to all staff, managers were rewarded on return on assets, and employee satisfaction results also contributed. The most successful form of pay for performance is gainsharing (Imberman, 1996). This is a group bonus plan aimed at modifying employee behaviour. The entire organisation work force-as a unit- is involved in an effort to exceed past performance. If successful, the gain is translated into cash and shared between the company and the employees. Normally, the work force receives 50 percent of the gain in bonuses, and the company receives an equal share in cost savings. This is gainsharing in its simplest form. Research (Imberman, 1996) revealed that this idea gave better results than employee involvement, quality circles, quality of work life, suggestion boxes or suggestion systems, profit sharing, labour management committees, Employees Share Ownership Plans (ESOP), job enrichment, information sharing, or TQM. In 1994, Crain’s Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 11 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 Chicago Business (Imberman, 1996) published a chart summarising the experience of 110 plant managers with their gainsharing programmes. 93% reported highly favourable results in productivity improvement. A milder form of gainsharing is ESOP, which are explicitly backed by the new Labour Government in the UK (Van de Vliet, 1996) and are expected to grow in acceptance especially as they are backed by tax provisions from the government. ESOP is essentially a trust that acquires shares in a company for the benefit of its employees. However, for employee share ownership to make a difference to company performance, it must combined with open-book, participatory management. This needs a shift to empowered teams and intensive communication. Still the whole process has to be thought through very carefully. Companies need to consider just how much of the equity employees should hold directly, and they constantly need to create new ways of making it attractive for them to hold on to these shares, otherwise employees might find the temptation to sell out irresistible (Van de Vliet, 1996). 2. Skill based pay Proposed best practice - Part of the reward should be payment for the number, type, or depth of the skills that people developed Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree of disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 20 40 60 80 100 Figure 7 Skill based pay – study results Another practice that is confirmed as best (78.8% approval). This system is known under various names like knowledge pay, skill-based pay and multi-skill based system, where pay increases are in line with the number skills acquired or developed. In practice the pay is determined by the variety of skills acquired or by the number of jobs that an employee is able to master with the underlying intent to encourage employees to acquire new skills, new knowledge, and increased versatility. More than 50% of Fortune 500 companies use skill based pay for at least some employees (Stivers and Joyce, 1997). This is indicative that companies believe there is a linkage between employee knowledge and competitive position. There are three forms of Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 12 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 skill development: vertical (upstream or downstream knowledge like acquiring more technical skills in a function or even acquiring management skills), horizontal (most frequently used and aim to offer the employees the possibility of acquiring a multitude of very diverse skills that are relatively alike in terms of degree of difficulty), and specialised (enable employees to acquire knowledge in a more narrow field of activities e.g. engineering). The skill based pay system increases functional flexibility enabling the company to counteract the effects of absenteeism, personnel turnover and capacity management. Moreover it is one of the most appropriate means of blending pay and total quality (Stivers and Joyce, 1997). Finally, the system offers employees more opportunities for growth and personal development and can reinforce the feelings of personal advancement and self-worth. However, it is dependent upon high access to training opportunities and the organisation needs to consider how to manage redundant skills. Moreover, it is generally not suitable for knowledge related jobs such as those in management. Toshiba (Kelada, 1997) applied skill based pay structure for its manufacturing and support operatives, e.g. those in the factory, in the stores, and in the offices. Management and professional employees were dealt with more along the lines of broadbanding. 3. Broad banding Proposed best practice - Seniority and length of service should not be the basis for promotion Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree of disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 20 40 60 80 100 Figure 8 Traditional promotion merits – study results 78% agreed with this statement thus confirming the broadbanding system as a best practice. The traditional ladder of seniority is no longer relevant to re-engineered organisations with multi-skilled, cross-functional teams. Supervisors and managers are not necessarily worth more to the company than specialists and professionals, and broadbanding can redress these inequalities (Brown, 1997). Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 13 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 Proposed best practice - Promotion must be based on role specifications or competency levels Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree of disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 20 40 60 80 100 Figure 9 Competency based promotion – study results Again, 76.8% agreed with this practice and confirmed it as best. This emphasised the need for a broadbanding system, especially for knowledge workers. At Volkswagen UK (Crainer, 1997), the principle is that ‘people are paid for what they can influence’, at Glaxo-Wellcome (Brown, 1997), ‘progress will be based on the demonstration of competencies rather than as a result of time in the grade. Competencies are about what the people do and how they behave, and the only behaviour that counts is that which delivers results. Competency is ultimately about performance’. In general, broadbanding (Brown, 1997) collapses a large number of hierarchical tiers and grades into a few bands often with very wide salary ranges, but it is not just about salary levels, it encompasses job evaluation, training and development, and almost always involves radical rethinking of how roles are described and what an individual employee can potentially offer the organisation. The aim is to encourage team-working and lateral career development over formal job grading. An essential feature is that pay rises are not dependent on promotion to a higher band, individuals can progress within their band, with pay rises for expanded roles or for new competencies (not to be confused with qualifications). In practice this means devolving responsibility for pay decisions to line managers who are supposedly better placed to monitor and evaluate their people than the HR department, which requires massive training for these managers. Broadbanding also makes more use of market data to track rates of pay outside the organisation and then uses this information to position individuals within bands. There are no hard and fast rules to broadbanding, it is a concept rather than a rubric and can be applied as management sees fit. Citibank (Brown, 1997) has introduced it for everyone except senior managers, while BP uses it only for its top 100 managers. The key Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 14 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 to its effective installation is proper communication which means comprehensive consultation with employees, and making the mechanics of the system very clear. Having broad bands in the same level will give employees unrealistic expectations which must be managed to avoid disappointment. The broad bands can be specified in terms of role specifications or levels of competency instead of traditional grades derived from qualifications, experience, length of service, and degree of responsibility (Brown, 1997). One of the great risks of broadbanding is that it appears to restrict the career opportunities for many employees, as there are many people whose scope for advancement is limited. There is always a need for people to do basic jobs which will render them always at the bottom of the pay band which is neither good nor morale. For this reason many organisations do not apply this broadbanding system to low-level manual or clerical jobs. 5. Appraisal and feedback Proposed best practice - Appraisal should focus on individual development and performance assessment Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree of disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 20 40 60 80 100 Figure 10 Appraisal aims – study results This proposed practice deals with the aims of appraisal and suggests realigning ‘traditional’ appraisal from pure performance assessment (to determine pay), to personnel development. 88.5% of the study participants agreed with this proposed shift and confirmed this concept as a best practice. Thus, there is a need for a new form of appraisal that takes the developmental approach. The first point to consider is the complete removal of the element of financial reward from the process. The principles of a developmental attitude include (Cane, 1996): 1. Develop human factors not financial targets to remove the competitive aspect from within the organisation and replace it with co-operation which will eliminate fear. 2. Link to business needs. Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 15 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 3. Run by team leaders or line managers who are in daily contact and observe the work of the employee. The personnel department can not be responsible for giving constructive feedback to a member of the staff from other people’s written comments 4. Open and participative 5. Single status - the appraisal process should include all staff (including management). 6. On-going and informal. The whole appraisal system should be embraced as part of a wider system of performance management. This means that it must embrace issues such as personal development and career planning. From the organisation’s point of view, the programme gives it the opportunity to liberate the potential of its employees, while the employees gain insights into what they can and can not do, where their career can go and how they can direct it (Crainer, 1997). Proposed best practice - The appraisal process should involve the employee, external customer, peers, and the team leader Disagree Strongly agree / agree 0 20 40 60 80 100 Figure 11 360 degrees appraisal – study results 76.8% agreed with this best practice and thus the annual appraisal should be re-invented to take the views of equals, subordinates, and customers as well as those of the direct supervisor. The traditional form of appraisal (one hour with the manager per year) was bureaucratic and did not actually improve performance (Crainer, 1997). The people that should be involved in the appraisal are the employees, peers, and the team leader, this is sometimes referred to as the 360 degree approach. All the people involved are asked to complete appraisal forms and send them to the PM function. The appraisal, to motivate and develop, will use two basic indicators: achievement against objectives, and achievement in skill and competency acquisition. Everyone receives the results in writing with statistics on their performance, strengths, areas for improvement, and some comments. Crucially, the process is anonymous (Crainer, 1997). Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 16 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 Traditionally, appraisals fell within the HR domain. Now, the PM function will be active in designing the appraisal process, take responsibility for training appraisers, the kind of questions asked, how people are measured and what the processes are seeking to achieve. It will act in a supporting role but the emphasis will be on working in partnership. Appraisals will be seen as a management tool which should be used by line managers (Covey, 1997). 6. Conclusions The study has identified several concepts and approaches relating to people reward, recognition and appraisal that leading organisations (and supporting literature) consider to be best practices. These practices included pay for performance, 360 degrees appraisal, interactive reward structures, and so on. There is no on single best practice system or formula for organisations to follow and implement. What the study has provided are well proven best practices that represent the pieces to a puzzle. Each organisation should take the appropriate ones and build their own picture that drives them and their people to excellence. The only constant in all the practices proposed is the emerging theme of people involvement. Organisations must learn to hand power down to the people who do the work and involve them in setting the reward schemes on a win-win basis, involve them in the organisational profits, and involve them in the appraisal and feedback system. This formula, coupled, with a shared vision towards the overall benefit of the organisation and its people is the true path for future performance excellence. Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 17 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 References Agrawal, Nresh, and Singh (1998) Organisational rewards for a changing workplace: an examination of theory and practice. International Journal of Technology Management. 16 (1–3), p. 225 – 238 APQC (1999) ‘What is benchmarking’, American Productivity and Quality Centre, www.apqc.org APQC (1996) ‘Benchmarking: leveraging ‘Best Practice’ strategies – a white paper for senior management’. American Productivity and Quality Centre, Texas, USA, 1995 APQC (1997) Identifying and transferring internal best practices. American Productivity and Quality Centre. USA Ashton, C. (1998) Managing best practices. Business Intelligence Limited: London. Brown, A. (1997) The pay bandwagon. Management Today. August, p. 66 - 68 Cane, S. (1996) Kaizen Strategies for winning through people - how to create a human resources program for competitiveness and profitability. Pitman Publishing: London. Carnall, C. (1997) Corporate Diagnosis, Carnall, C. Ed. (1997) Strategic Change. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinmann. Chase, R. (1997) The knowledge-based organisation: An international survey. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1 (1), p. 38-49 Cooper, R.; and Markus, L. (1995) Human Reengineering. Sloan Management Review. Summer, p. 39 49 Covey, S. (1997) Putting Principles First, in Gibson, R. ed. (1997) Rethinking the future. UK: Nicholas Brealey Publishing Ltd. Crainer, S. (1997) Feedback to the future. Management Today. June. p. 90 - 92 Decker, D.; and Belohlav, J. (1997) Managing Transitions. Quality Progress. 30 (4), p.93-97 DTI (1995) Tomorrow’s Best Practice – a vision of the future for top manufacturing companies in the UK. DTI: London Druker, P. (1992) ‘The new society of organisations’, Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct, p. 95 – 104 Fowler, F. (1993) Survey Research Methods. Applied Social Research Methods Series, 1. London: SAGE Publications. Hale, J. (1998) Strategic rewards: keeping your best talent from walking out the door. Compensation and Benefits Management. Summer, p. 39 – 50 Imberman, W. (1996) Gainsharing: A lemon or lemonade. Business Horizons. 39 (1), p. 36-40. Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 18 Research Paper: RP—ECBPM/0033 Kanter, R. (1989) ‘The new managerial work’, Harvard Business Review, Nov-Dec, p. 85 – 92 Kelada, J. (1996) Integrating Reengineering with Total Quality. ASQC Quality Press: Wisconsin. Kerr, S. (1998) Organisational rewards: practical, cost-neutral alternative that you may know, but don’t practice. Organisational Dynamics. p 61 – 70 Lee, R. (1996) The ‘pay-forward’ view of training. People Management. 8 February. p. 30–32 Littlefield, D. (1996) Wages must reward skills and innovation, People Management, 8 February, p. 13 Loomba, A. and Jonanessen, T. (1997) MBNQA – critical issues and inherent values. Benchmarking for Quality Management and Technology. 4 (1), p. 59 – 77 Oram, M. and Wellins, R. (1995) Re-engineering’s Missing Ingredient - The Human Factor. London: Institute of Personnel Development. Quinn, J. (1996) How can you motivate in an environment like this. Incentive. June. p. 30 –55 Reger, R.; Mullane, J.; Gustafson, L.; and DeMarie, S. (1994) Creating earthquakes to change organisational mindsets. Academy of Management Executives. 8, p. 43 – 44 Slater, S. (1995) ‘Learning to change’, Business Horizons, Vol. 38, No. 6, p. 13 – 18 Stivers, B. and Joyce, T. (1997) Knowledge management focus in US and Canadian firms. Creativity and Innovation Management. 6(3), p. 140 – 150 The Industrial Society (1996) Managing best practices – employee development. Number 30. London Van de Vliet, A. (1997) ESOP’s fable becomes a reality. Management Today. November. p. 112 - 114 Willets, L. (1999) Human resources: first stop for reengineers – many companies target the back office. Re-engineering Resource Centre. www.reengineerng.com/articles/ Wunsch, D. (1986) “Survey Research: Determining Sample Size and Representative Response”. In Business Education Forum, Feb, p. 31-33 Copyright © 2010 www.ecbpm.com Page 19