Effects of Working Capital Management on Company

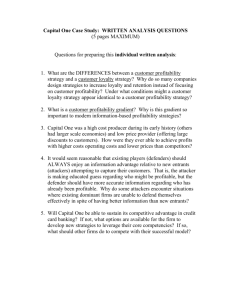

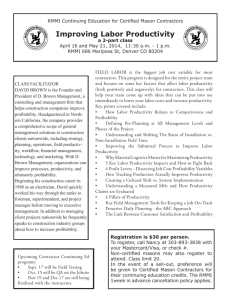

advertisement