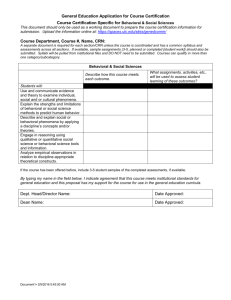

DEVELOPMENT OF BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE AND THE

advertisement