In Memory of A Once Fluid Man - Spartan Fund Management Inc.

advertisement

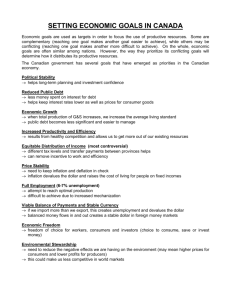

“In Memory of A Once Fluid Man” 2014 Year End Letter One International Place 100 Oliver Street, Suite 1400 Boston, MA 02110 T: 617.229.6401 // F: 617.229.6403 January 13, 2015 Dear Investor: Prior to the emergence of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) in the 1990’s, most “classical” martial arts styles had mutated into something that likely would have been unrecognizable to their progenitors. The martial arts had become ossified by conformity and credentialism; they were rarely combat-tested and— combined with a belt ranking system—lulled practitioners into a false sense of martial skill. Bruce Lee encapsulated this state of affairs in a famous epitaph: “in memory of a once fluid man, crammed and distorted by the classical mess.” Change was forced upon the martial arts world in the 1990’s when a family of Brazilian martial artists developed an ingenious business plan to market their art. They held UFC tournaments featuring martial art masters from different disciplines—regardless of size and strength—facing off against each other in no-holdsbarred competition. The results of the earliest tournaments are readily available on YouTube for those with strong stomachs. Black belts boasting decades of experience learned that most of what they thought they knew was wrong. Unfortunately, they frequently learned their lessons the hard way: when their teeth were knocked out and sent flying across the ring. There are two distinct paths that one can take when reality shatters one’s belief system: one can return to the drawing board, adapt one’s processes, and more closely match one’s mental map to the terrain of reality; or one can embrace the cognitive dissonance and double down on one’s delusions. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 could have been the clarion call that ushered in a new, reality-based era of economics and investing. Instead, investment and economics practitioners doubled down on their delusions. The problem is not that they learned nothing from the experience, but rather that they learned all of the wrong lessons—and were handsomely rewarded for doing so. The Emperor Has No Clothes Only six years have elapsed since one of the most devastating bear markets in history—a bear market that nearly resulted in the complete collapse of the global financial system—and yet the most salient features of the typical economic discussion are: • • • • • • • • the assiduous state of denial and complacency; the rote assertion of a genus of long-discredited economic fallacies; a lack of introspection regarding systemic failures in the mainstream analytical and investment processes and methodologies; the belief that 2008 was a one-off “1000-year flood” that has been fully resolved and that we are now once again off to the races; an unshakeable belief in the omnipotence of central bankers and central planners; a disdain for the understanding and management of risk; the wholesale absence of fear concerning debt and deficits; and ridicule towards anyone who observes that the emperor is naked. The post-modern surrealism of the past year is best captured in a recent letter written by a hedge fund manager that we respect. This fund manager is extremely intelligent—he foresaw the 2008 crisis and profited from it— and yet now openly praises the Emperor for His new clothes while embracing Greater Fool Theory: There are times when an investor has no choice but to behave as though he believes in things that don't necessarily exist. For us, that means being willing to be long risk assets in the full knowledge of two things: that those assets may have no qualitative support; and second, that this is all going to end painfully….So I have come to embrace the French philosopher Baudrillard's insight. "Truth is what we should rid ourselves of as fast as possible and pass it on to somebody else," he wrote. "As with illness, it's the only way to be cured of it. He who hangs on to truth has lost." The economic truth of today no longer offers me much solace. Monetary Illusion & The Myth Of Central Bank Omnipotence It is easy to succumb to the Whig view of history—that of perpetual progress—and to forget that the monetary system that we now take for granted is merely an experiment. Bretton Woods II is, in fact, the first-ever global experiment of its kind: a floating paper money regime. This particular experiment is barely 45 years old, however thousands of years of economic history are littered with worthless paper money attesting to the fact that it is unlikely to yield positive results. As a consequence of the monetary system’s fatal design flaws, the world has careened from financial crisis to financial crisis since its inception in 1971, issuing ever-greater amounts of money and debt to paper over past crises—until the system itself nearly collapsed catastrophically in 2008. The coordinated global response to 2008— ballooning central bank balance sheets, zero (not to mention negative) interest rates, “quantitative easing”, record government deficits/spending, etc.— represents an unparalleled period of free money, dwarfing even the then-unprecedented period that preceded (and caused) the 2008 crisis. We have become inured to just how revolutionary the period that we are living through truly is: “Quantitative Easing” and “Abenomics” are casually discussed on CNBC and the WSJ daily, and the world’s central bank chiefs have not only become household names but are now widely deemed to be omnipotent. The BIS—the so-called central bank to the world's central banks—commented recently on the absurdity of the situation: “Recent events…have highlighted once more the degree to which markets are relying on central banks: the markets' buoyancy hinges on central banks' every word and deed.” Credit Expansion & Economic Surreality Credit expansion, as Ludwig von Mises prophetically observed, is “governments’ foremost tool in their struggle against the market economy. In their hands it is the magic wand designed to conjure away the scarcity of capital goods, to lower the rate of interest or to abolish it altogether, to finance lavish government spending, to expropriate the capitalists, to contrive everlasting booms, and to make everybody prosperous.” The power to print fiat money is a staggeringly effective tool for deceiving the masses. When money is free, it creates the illusion that everyone can temporarily defy gravity: they can engage in all manner of foolhardy activities while surfing on waves of easy credit, seemingly un-beholden to the laws of economics, yet never suffer any repercussions for their folly. As a result of their interventions post-2008, central banks have shattered any semblance of economic reality and unleashed upon us the greatest financial bubble and speculative orgy in history, converting global financial markets into full-fledged casinos. We now bear witness to: • • • • • • • hitherto unimaginable financial excesses across nearly all markets; a world-wide housing and consumption bubble; a massive increase in debt pyramided on top of yet more debt; a global sovereign debt bubble featuring such absurdities as the lowest European bond yields since the Black Plague; a collapse in private savings and production; an alarming embrace of central planning and interventionism; and a proliferation of morally questionable and outright fraudulent activities. Although the enormity of the current situation is breathtaking in light of its sheer scale, none of its effects should come as a surprise to those versed in economic history. Henry Hazlitt presciently noted in his forward to Fiat Inflation In France that: 2 The broad pattern of all [money and credit] inflations, historical and modern, is the same. The first result is commonly the ‘recovery’ that the inflationists, like others, are seeking. It is not until later that its disappointing and poisonous effects become apparent...This is because the kind of production stimulated by inflation even at the beginning is an unbalanced production (owing to the money illusions that inflation creates) and because inflation finally encourages merely malinvestment, thriftlessness, speculation, and gambling at the expense of production itself. Credit Parabolas And Asymptotes Once an economy “cheats” by creating debt in excess of savings, debt growth must remain on a parabolic curve or the economy and financial system will crash. Each successive bubble must cover up the preceding bubbles’ level of malinvestment and bad debt—and then some—to continue its artificial level of growth. Financial parabolas therefore become increasingly unwieldy the larger they become. The problem facing the world now is that the amount of credit growth required to temporarily postpone the detonation of these malinvestments has become almost impossibly large, and undertaking such an extraordinary credit expansion would almost assuredly result in the eventual catastrophic collapse of the monetary system. As Ludwig von Mises famously warned: There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as a result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved. Canada, Easy Money, And Recency Bias Canada—widely considered to be the safest financial system in the world—is in reality a poster child for the ill effects of easy money described in the preceding pages. Paul Kedrosky drew attention to an academic study analyzing the perception of volcanic risks over time and its implications for “recency biases”: We [tend to] overweight near-term events and underweight everything else, [which wreaks] havoc in financial markets. It causes us to think of the last few years as normal, whether it’s housing, technology stocks, equity multiples, or the ease with which you can raise venture capital. It generally takes a crisis to disabuse us of the idea, which is an awfully high price to pay when the alternative is simply paying slightly more attention to history. While “recency bias” superbly describes the current attitude of the investment world in general, Canadians have managed to carry this mindset to an extreme. Twenty five years have elapsed—an entire generation—since the last credit and housing bust in Canada and as a result, recency biases are firmly entrenched in the Canadian psyche. Canadians fervently believe in their own exceptionalism and that their housing market and financial system are immune from a US-style meltdown despite a host of metrics which indicate that caution is warranted: 3 House Prices : Rents House Prices : Incomes House Prices : Per Capita GDP Home Ownership Rate FIRE* % GDP Residential Construction % GDP FIRE* % Stock Market Earnings HELOC** % GDP FIRE+related Employment % GDP Household Debt % GDP Household Debt % Disposable Income Govt. Sponsored Entities % GDP *FIRE: Financials, Insurance, & Real Estate *HELOC: Home Equity Line of Credit Canada 2013 200% 12x 7x 70% 20% 7% 46% (TSX) 12% 14% 95% 164% ~30% (CMHC) US 2007 127% 8x 6.5x 69% 18% 6% 30% (SPX) 4.5% 11% 94% 128% ~33% (FNM/FRE) Throughout much of 2014, however, there were few overt signs of stress in the Canadian housing and credit markets—confirming Canadians’ biases—and housing bubble observers were widely ridiculed. 2015: The Perfect Storm For Canada By the end of 2014, however, virtually every tenet undergirding the Canadian housing bull case had been called into question: • • • • • • • • a host of bellwether Canadian financial companies missed earnings expectations; energy prices plummeted; the Bank of Canada and mainstream media finally caught on to the fact that Canada is home to a booming subprime auto, farm, and mortgage market; the Bank of Canada warned that house prices could be 30% overvalued; CMHC—Canada’s government-backed mortgage insurer—beefed up hiring for “risk management” purposes; Canadian consumer credit grew at its slowest pace in decades; Chinese credit growth slowed, resulting in a weak Chinese housing market and economy; and the Chinese government launched a serious crackdown on corruption (particularly targeting money laundering and overseas assets in places such as Canada). As the pseudonymous Pater Tenebrarum explained: Bubbles don’t burst because of a “black swan” [a supposedly unpredictable event]: rather the swan – often a combination of events that makes it impossible to identify a single trigger – is a diffuse trigger mechanism that sets into motion what is already preordained. It is the famous “one grain too many” that is put atop a giant sand pile – however, it is the sand pile that is the problem, not the one grain. This is also why precise timing of a bubble’s demise is so difficult – it is unknowable what exactly will actually lead to the change in perceptions that ultimately provokes the unwinding of the leverage that has been built up. With Tenebrarum’s wisdom in mind, we think that the coming year could prove to be the perfect storm for Canada—one that will potentially burst the Canadian housing and credit bubble. The Fund is positioned to profit asymmetrically from the bursting Canadian housing bubble. 4 The five most significant risks constituting this perfect storm for Canada are: 1) Peak credit in Canada; 2) The collapse of oil; 3) China’s mounting credit and housing problems; 4) China’s anti-corruption campaign; and 5) The strong US dollar’s impact on un-hedged dollar-denominated debt and carry trades. We will consider each risk factor in turn. Peak Credit In Canada Our theory has been that a decline in the growth of credit will reveal cracks in the Canadian housing bubble edifice. Canadian consumer debt grew at its slowest rate in two decades in 2014, the result of an over-saturation of household debt combined with governmental policies that constrained mortgage availability after a decadelong subprime mortgage binge. CMHC’s balance sheet (insurance-in-force) uncharacteristically contracted year-over-year at the end of 2014. The declining availability of CMHC insurance has forced banks to become more cautious since they now risk their own capital rather than taxpayers’: recall that 70% of the Canadian mortgage market is of such dubious quality that the banks refuse to lend at their agreed-upon terms without some sort of guarantee from the government that they will be made whole in the event of a default. The result of CMHC’s recent balance sheet contraction has been that marginal borrowers were pushed down the credit ladder and now pay a higher interest rate for loans—assuming that they can obtain a mortgage at all. If they cannot, they will be shut out of the housing market entirely—or worse yet become forced sellers of their homes. The majority of Canadian loans are for 5-year terms, and that the riskiest segment of the market borrows for 1-2 year terms; therefore the credit tightening will likely propagate through the structure of the mortgage market more quickly than it would if loans were fixed for 15- or 30-year terms as is typically the case in the US. Ominously, CMHC itself began to see a deterioration in its financial stress statistics in Q3/14—rising claims paid, claims losses, severity ratio, and loss ratios—indicating deteriorating credit quality in the Canadian economy: 5 Canadian Financials’ Q3/2014 Earnings Season Our thesis began to play out when a cluster of bellwether Canadian financial companies missed Q3 (September 2014) earnings estimates, indicating that a potentially seismic shift is under way in the Canadian economy. What is most interesting is that the Canadian economy and housing markets appeared superficially strong in Q3, and crude did not begin its plunge in earnest until October. We have—unfortunately—seen this movie play out before. First, the refrain was “there is no such thing as subprime in Canada”; now we hear “of course there is subprime, but it’s a negligible part of the market”; next it will be “contained to subprime”, at which point any sentient being will have long since fled for the hills. Towards the end of the credit cycle, analysts find it perfectly reasonable to price financial companies on a forward price to earnings (P/E) ratio, and argue that the stocks look cheap based on this metric. As the bullcase narrative implodes and companies miss earnings, analysts fall back on the argument that we are merely witnessing a temporary setback. As it begins to sink in that the earnings misses are not in fact temporary, analysts fall back on price-to-book valuation metrics, arguing that several multiples of book valuation is reasonable given that the financial institutions’ balance sheets are pristine. Then, when credit inevitably deteriorates, the Street begins to question book values at the same time that book value multiples compress: what once looked reasonable at 2x book now trades 80% lower as the book value is written down due to losses and price-to-book multiples compress. Credit Deterioration & Booming Private Lending For the first time in this cycle, subprime lenders reported disappointing earnings, declining margins, and signs of deteriorating delinquencies. It appears, ironically, that subprime lenders missed estimates partially due to margin erosion from increased competition at the bottom of the subprime food chain as a result of CMHC’s credit tightening. Easy credit in the non-CMHC segment has fueled a frenzy in the sub-subprime “private lending” market that is now cannibalizing the subprime market. A small mezzanine lender discussed how aggressive private lenders have become in its Q3 outlook—bear in mind that this firm lends a notch below subprime: [...] we continue to feel that there is an overabundance of capital in the real estate market which can lead to real estate overvaluation and has led to inexperienced lenders and landlords/developers entering the market. The overabundance of capital in the market has resulted in borrowers requesting loan structures that incorporate either too much risk exposure or too little return for the loan parameters. This race to the bottom and margin compression indicates that lenders are getting paid less to take on more risk at the very top of the credit cycle. Energy: The Collapse Of Crude The price of crude oil plunged by 50% in the second half of 2014—the third largest drop in half a century, surpassed only by the slumps that followed Lehman’s default in 2008 and the breakdown of the OPEC cartel in 1985. The tremors are only now beginning to be felt around the world; markets are underestimating the potential systemic implications of oil’s price shock for large numbers of highly levered companies, industries, and economies in 2015. While lower oil prices are widely seen as a net boon for the global economy, this naïve view ignores—inter alia—the lessons of the 1998 Russian and LTCM crises, and that the global financial system is even more leveraged and interconnected today than it was in 1998. Oil’s Impact on Canada The decimation of the energy complex will send shockwaves throughout Canada, causing extensive labor market disruption and deteriorating credit quality at a time when Canada has never been less resilient due to the back-breaking consumer debt levels underpinning its overvalued housing market. Crude’s collapse will: 6 • • • • • • bankrupt the marginal Western energy producers; delay and cancel new oil sands projects; ravage provincial coffers; have negative implications for Canadian household income and debt serviceability; erode household wealth (energy represents nearly a quarter of Canadian equity market capitalization); and impair the profitability of major Canadian financials (which in turn represent nearly half of TSX earnings). Oil’s Impact on Canadian Labor Alberta has shouldered responsibility for over 70% of full-time job creation in Canada since 2011: Source: Ben Rabidoux/North Cove Advisors This has—unsurprisingly—been the result of booming energy prices: Source: Ben Rabidoux/North Cove Advisors Oil’s Impact On Canadian Credit Quality The improvement in mortgage arrears in Alberta—a non-recourse mortgage jurisdiction—has been responsible for 90% of the improvement in the national arrears rate since 2012: 7 Source: Ben Rabidoux/North Cove Advisors Calgary’s Housing Market Bodes Ill For The Rest Of Canada As an early portent for the rest of the nation, new home listings in Calgary reached an all-time high for the month of December, and December sales-to-new listings (a rough proxy for supply/demand in the housing market) notched its second worst reading since 2000 (only 2008 was worse). Seasonally, sales-to-new-listings declined month-over-month from Nov-Dec for only the second time on record (the only other time this occurred was 1989). The situation appears to have deteriorated further in January, with sales down 34% yearover year and average prices down 5.8%. Condo sales in Calgary are faring even worse, down 41% year-overyear so far in Jan, new listings are up 71%, and active listings are up 79%. Provincial Fall-Out: Equalization Payments Although the western provinces will be hard hit, ironically it is the over-indebted Eastern provinces that are most at risk. The Canadian government follows the Marxist dictum to redistribute wealth “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”, and directly transfers payments from wealthy Canadian provinces to less wealthy provinces in order to equalize the provinces’ “fiscal capacity”. Taxes and royalties derived from the oil sands regions are redistributed to six “have-not” provinces (e.g., Quebec, Ontario, and the Atlantic provinces) representing a collective 70% of the Canadian population. Take Quebec as an example: it boasts one of the worst sub-sovereign fiscal positions in the world, and in 2015 will (supposedly) attempt to claw its way back to some semblance of fiscal sanity by implementing an austerity budget. The near-term problem is that austerity coupled with falling transfer payments as a result of the oil shock will only exacerbate Quebec’s already-serious economic difficulties and dangerously-imbalanced housing market: every job created in Quebec since 2011 has either been in the public sector or in the construction sector. Income Impairment/Debt Serviceability/Contagion Income impairment represents another conduit for contagion from the oil sands: a not-insignificant portion of the income earned in the oil sands has supported incomes, credit origination, and home prices in Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces. Recent press articles highlighted the prevalence of “oil patch fly boys”— the huge shadow population of workers that fly in and out of the oil sands regions. Troubles in the oil sands will therefore threaten not just Albertan but rather nation-wide incomes, debt serviceability, and house prices. Further weakness in energy will likely detrimentally impact the financial industry, resulting in bank layoffs, restructurings, lower bonuses, etc. Note that in Toronto, for example, the FIRE industry (finance, insurance, real estate services) as a whole represents nearly 30% of GDP and has been responsible for 42% of total GDP growth in the past decade. 8 China Who hasn’t heard stories of endless waves of Chinese investors arriving in Vancouver with cash-filled suitcases eager to buy condos? To the extent that the “Hot Asian Money” stories were genuine, they will likely become more rare in the future due to a sweeping corruption crackdown, slowing Chinese credit growth, an impaired shadow banking system, and a weakening Chinese economy. The consensus holds that China’s central planners will engineer a soft landing for their command-and-control economy. Others more erudite than myself have analyzed China’s structural difficulties in great detail, so I will merely skim over the highlights. Beginning in 2008, China undertook a Keynesian-style economic stimulus to fend off recession by levering up on a mind-boggling amount of debt to build uneconomic industrial and infrastructure malinvestments (ghost cities, ghost factories, ghost airports, etc. etc.). Loans have skyrocketed at double the rate of growth witnessed in Japan prior to its stock market crash in 1990 and double the US growth rate prior to its 2008 crisis; debt now represents 250% of Chinese GDP. As with any pyramid scheme, once new money stops flowing in, the scheme collapses. China’s debt growth decelerated significantly in 2014 and the system immediately exhibited signs of stress: • • • • • China admitted to its first-ever corporate default of this cycle, and a handful of small companies followed suit; China’s Q3/14 bad debt increased the most since 2005; housing faltered nationwide for the first time; China announced in October that it would not bail out debt-laden local governments, igniting liquidity issues (recall that up to half of local governments’ revenues are derived from land sales, which are currently plummeting); and all manner of frauds and risks were uncovered in the so-called shadow (non-bank) banking system. In short, the Chinese pyramid scheme began to collapse under its own internal contradictions. China’s Growing Liquidity Problem: Kaisa’s Default On Jan 1, 2015, a publicly-traded Chinese property developer—Kaisa—defaulted on $50milUSD of loans. This is a watershed event: it represents the first well-known, publicly-listed Chinese company to default. Kaisa boasted a $2bilUSD market cap as recently as November, and its debt is held outside of China. Kaisa highlights a growing liquidity problem in China. Chinese corporations have recently indebted themselves to the tune of $1-$2 trillion in risky short-term, externally (foreign) funded debt. China’s real-estate firms in particular borrowed heavily overseas, and are now suffering as the US dollar appreciates and China’s house market deteriorates. The Chinese government’s ability to contain defaults and sustain zombie corporations was relatively simple when the debt level was more manageable and bonds were primarily held domestically (China “successfully” spent 15% of GDP to bail-out its banks in the 1990s). Concealing cascading cross-defaults is another matter altogether today given the sheer scale of China’s indebtedness and the fact that foreign investors are now involved. While a solitary default is unlikely to shut Chinese corporates out of the foreign capital markets, it will certainly make it more difficult (and costly) for them to borrow abroad in the future—which could rapidly translate into defaults since many of these firms are reliant on the capital markets to roll over old debt. Chinese regulators created additional liquidity strains in December by pushing up funding costs for borrowers by removing riskier bonds from the funding channel. This could trigger further local government and corporate bond defaults. 9 China’s Wealth Trust Funds & Shadow Banking The at-risk corporate bonds described above are likely heavily-owned by wealth management products known as Trust funds, a pillar of China’s shadow (non-bank) lending market. These Trust funds could face their own liquidity issues (i.e., fail to roll over debt) as a result of corporate bond defaults such as Kaisa’s—potentially creating a negative credit feedback loop. For an economy such as China’s—one in which credit creation is paramount—any impairment of the shadow banking system could lead to a significant credit crunch. Recall that China’s $2 trillion Trust fund industry grew eight-fold since 2008, and triggered turmoil in the emerging markets in January 2014 when a near-default prompted scrutiny towards the risky financial instruments. The greatest systemic risk is not necessarily the Trusts themselves but rather the daisy-chained web of guarantees and collateral in their contracts—and inherent to the Chinese financial system in general. China’s Commodity Financing Deals (CCFDs) Another pillar of the Chinese shadow banking market that ran aground in 2014 were so-called Chinese Commodity Financing Deals (CCFDs), whereby firms used commodities (e.g., copper) as collateral to secure loans that were frequently used to speculate on Chinese real estate. CCFDs originated as an interest rate arbitrage and a bet on the biggest one-way trade of the past fifteen years—yuan appreciation against the US dollar. CCFD participants semi-legally imported prodigious quantities of commodities in order to use relatively cheap (and until recently, dependably depreciating) US dollars to fund speculative positions first in Chinese housing and more recently—as the Chinese housing bubble deflated—in the Shanghai-listed equity bubble. CCFDs rapidly devolved into an outright pyramid scheme, whereby too many paper receipts (claims on assets) were issued relative to the actual underlying assets (e.g., copper), and in 2014 they ran into difficulty due to a strengthening US dollar, collapsing commodity prices, and a series of high-profile scandals (e.g., it was revealed that the putative underlying assets at the base of the pyramid scheme frequently didn’t even exist in the first place!). The Collapse of Macau & VIP Junket Operators Another key aspect of China’s shadow banking system, so-called “VIP junket operators”—consisting of businesses that lend to high-rolling gamblers and connect them with Macau casinos—imploded in 2014 as a result of the mainland credit crunch and the government’s anti-corruption crusade. VIP gamblers comprised approximately two-thirds of Macau’s billion-dollar gaming market. In April, shortly after the Chinese credit crunch began, a VIP junket operator absconded with $1.3 billion of investor funds. This high-profile embezzlement, combined with a crackdown on corruption and a slowdown in China’s economy had the effect of squeezing junket operators by chasing away VIP gamblers (hurting revenues), and causing a “bank run” as junket investors rushed to get their money back (setting off a cash crunch among the survivors). China’s Anti-Corruption & Money Laundering Campaign China launched an anti-corruption campaign—“Operation Fox Hunt”—two years ago, but the crackdown only began in earnest during the summer of 2014. This bodes poorly for Chinese demand for Canadian houses in 2015. While past corruption crackdowns had primarily been ornamental, the ferocity of Operation Fox Hunt appears to be the unparalleled in the nation’s history and is perhaps motivated by a desire to purge political dissidents. A recent editorial published in China’s military newspaper stated that the government’s determination to eliminate corruption is “unswerving” and that it is a “mistake” to expect that the campaign will end in the near future. Macau is widely reputed to be a conduit for bypassing capital controls through which corrupt officials and economic criminals funnel money from China to safe havens such as Canada, Australia, and the U.S. Australia 10 announced in October that they would cooperate with the Chinese government to retrieve embezzled funds that had been siphoned into their country; Canada followed less than a month later with a similar deal. An announcement in December that the Chinese government will stamp out money laundering in Macau sent casino shares into a tailspin; over $75bil of market cap was wiped out in 2014 as casino revenues plunged 30+% year-over, suffering their first-ever annual decline. China in January announced its intentions to collect taxes from citizens living abroad. While Hong Kong is likely the true target of these measures—and will be the hardest hit—it will negatively impact Canada, Australia, and other destinations for Chinese money flows. Chinese As “All Cash Buyers”: The Case Of Hong Kong Luxury Houses While it may appear to Canadians that Chinese borrowers are paying cash in Vancouver for houses, what is not seen is that the Chinese have piled on the debt back home. Slowing Chinese debt growth and a faltering mainland housing market triggered a margin call on Hong Kong luxury real estate (a proxy for Chinese housing activity in Canada and Australia), belying the notion that the Chinese are truly “all-cash” buyers abroad. A March 2014 Reuters article observed that “cash-strapped Chinese are scrambling to sell their luxury homes in Hong Kong, and some are knocking up to a fifth off the price for a quick sale, as a liquidity crunch looms on the mainland.” Retailers in Hong Kong—a shopping center for Chinese tourists—also suffered. Sales of luxury retail goods in Hong Kong fell 12% year over year in October. Even before September’s protests in Hong Kong, sales of high-end consumer items had fallen for seven straight months through August. Hong Kong retail store rents are on track for their worst year since the global financial crisis. Myth of China As Economic Savior The mainstream assumes that China can support the rest of world due to its “internal growth engines”; i.e. China can seamlessly transform itself from a credit-dependent, mercantilist industrial economy to a domestic consumer-based services powerhouse. However, even setting aside the long-discredited economic fallacies inherent to such a view, China itself is at mounting risk of a financial crisis in 2015 as credit growth slows and house prices weaken. It’s not at all clear that China will be able to save itself—let alone the rest of the world. China’s unprecedented credit expansion post-2008 elevated investment in infrastructure and in property development. Rising property prices and the demand created by construction activities created wealth effects and raised labor wages, both of which drove consumption growth. Slowing credit in 2014 revealed the unsustainable nature of China’s boom, however, and resulted in an average 10% drop in housing transaction volumes in 2014 as well as home prices that declined nation-wide for the first time. The toll on China’s economy was immediate and severe: • • • • • • cement, steel, coal, copper, and iron ore prices plummeted; excavator and truck sales volumes crashed; inventory remained near historical highs across the entire (highly-leveraged) supply chain from idle purchased land, to finished property, to steel bars, to iron ore; electricity usage and rail-freight traffic dropped; the Baltic Dry Index (considered a leading indicator of future global economic growth) plumbed its lowest level since records began; and retail and casino revenues declined precipitously. China’s Lehman Moment: A Tiger By The Tail We are rapidly approaching the point at which the Chinese central bank will be forced to decide whether to monetize the bad debt when it comes due and/or defaults, or to face the equally unpalatable consequences of letting the debt default. Unfortunately, the scale of debt and malinvestments now make it exceedingly difficult for China to “stimulate” the economy by printing money, and doing so will certainly cause extensive collateral damage. To quote the Nobel-laureate Friedrich Hayek, China has caught “a tiger by its tail”. 11 If China monetizes the debt, it is likely to further devalue the yuan—potentially leading to inter alia: • • • • • • • a liquidity crisis as a result of the sizable amount of unhedged dollar-denominated debt issued by Chinese companies; cascading cross-defaults emanating from its shadow banking system (including CCFDs, which are partially predicated on a continually appreciating yuan against the US dollar); increased pressure on Chinese exporters as a result of the current exchange rate (despite China’s benign reported export numbers, which are even more dubious than the rest of the official statistics) rising food and energy costs that could foment civil unrest; another leg down for oil as Chinese are less able to afford it (China is the largest importer of oil in the world); draining money flows out of its stock market; the possibility for a currency crisis if hot money flows out of the country in a disorderly fashion. If China is unwilling or unable to expand credit at a sufficient rate, the likely outcome is that: • • • credit deflates; real estate plummets; and massive defaults loom as the economy falls off of the financial parabola and widespread malinvestments are purged; In short, China appears to be trapped between Scylla and Charybdis. Strong USD = Emerging Market Pain The US dollar strengthened dramatically in 2014. The problem is that the emerging markets in particular have borrowed heavily in the U.S. dollar denominated debt markets, so the recent dollar strength is equivalent to an interest rate hike for these un-hedged borrowers. A strong US dollar also pressures the massive “dollar carry trades” (such as the CCFDs discussed earlier)– leading to a feed-back loop that has sustained the dollar’s appreciation. It is possible that recent troubles in the emerging markets (e.g., Russia) may indicate a bursting of the global government finance bubble that has taken root since 2008. Emerging market debt is the global sovereign system’s weakest link, and dollar-denominated emerging market debt in particular may represent the canary in the coal-mine. If the dollar’s strength continues unabated, recent emerging market difficulties have the potential to intensify into a full-blown crisis if unwound in a disorderly fashion. Conclusion We expect that the confluence of macro events described above will cause stress in the Canadian housing market and the broader Canadian economy. While the Fund is positioned to conserve capital in the event that we are mistaken, we will profit asymmetrically if even a single one of the aforementioned risks comes to pass. Thank you for entrusting us with your capital. Best regards, Seth Daniels Managing Partner JKD Capital, LLC 12