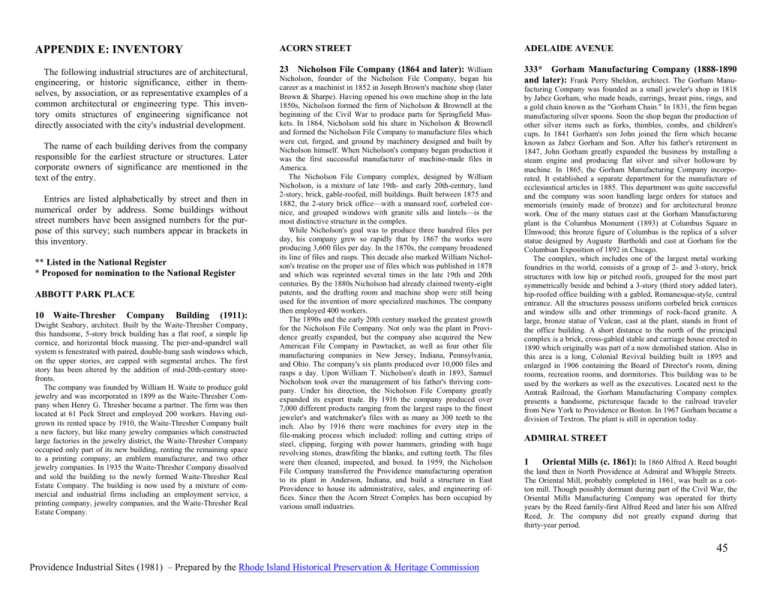

appendix e - Little Rhody's List of Rhode Island Information

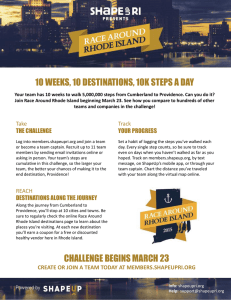

advertisement