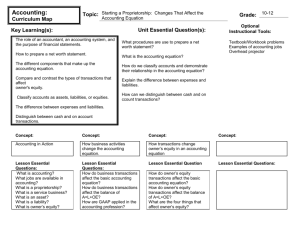

Reading and Understanding Financial Statements

advertisement

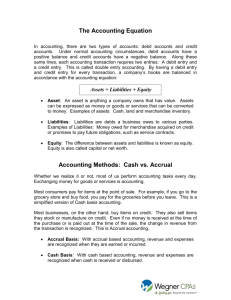

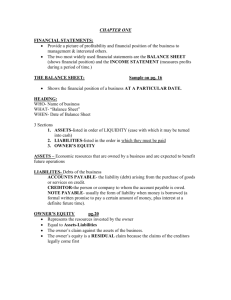

LAWYERS’ USE OF FINANCIAL STATEMENTS PAPER 1.1 Reading and Understanding Financial Statements These materials were prepared by Kiu Ghanavizchian, CA, CBV, MBA, of Blair Mackay Mynett Valuations Inc., Vancouver, BC, for the Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia, March 2013. © Kiu Ghanavizchian, CA, CBV, MBA 1.1.1 I. Reading and Understanding Financial Statements A. Basic Terms & Definitions Assets Economic resources controlled by an entity and which are likely to generate net cash flows in the future. Liabilities Obligations of an entity which will likely require a sacrifice of resources in the future (net cash outflow). Equity (aka Shareholders’ equity or Net assets) The residual ownership interest which remains after an entity’s liabilities are subtracted from its assets. Revenues Increases in economic resources either by way of increases in assets or reductions in liabilities which arise from an entity’s normal business operations. Revenues are a component of equity. Expenses Decreases in economic resources either by way of increases in liabilities or reductions in assets which arise from an entity’s normal business operations. Expenses are a component of equity. Net income (loss) The amount of profit (or loss) which remains at the end of a particular period after an entity’s expenses are deducted from its revenues. Net income or loss is a component of equity (by virtue of the fact that revenues and expenses are components of equity). B. Objectives of Financial Statements1 Ownership of profit-oriented enterprises is often segregated from management, creating a need for external communication of economic information about the entity to investors. For the purposes of this section, investors include present and potential debt and equity investors and their advisers. Creditors and others who do not have internal access to entity information also need external reports to obtain the information they require. In the case of financial institutions, investors, creditors and others include depositors and policyholders. Members of and contributors to not-for-profit organizations are also often segregated from management creating a similar need for external communication of economic information about the entity to members and contributors. A not-for-profit organization's creditors and others who do not have internal access to entity information also need external reports to obtain the information they require. 1 This material was obtained from Part II – Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises (Section 1000 – Financial Statement Concepts) of the CICA Handbook, published by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants. 1.1.2 It is not practicable to expect financial statements to satisfy the many and varied information needs of all external users of information about an entity. Consequently, the objective of financial statements for profit-oriented enterprises focuses primarily on information needs of investors and creditors and, for not-for-profit organizations, focuses primarily on information needs of members, contributors and creditors. Financial statements prepared to satisfy these needs are often used by others who need external reporting of information about an entity. Investors and creditors of profit-oriented enterprises are interested, for the purpose of making resource allocation decisions, in predicting the ability of the entity to earn income and generate cash flows in the future to meet its obligations and to generate a return on investment. Members, contributors and creditors of not-for-profit organizations are interested, for the purpose of making resource allocation decisions, in the entity's cost of service and how that cost was funded and in predicting the ability of the entity to meet its obligations and achieve its service delivery objectives. Investors, members and contributors also require information about how the management of an entity has discharged its stewardship responsibility to those that have provided resources to the entity. Information regarding discharge of the stewardship responsibilities is especially important in the not-for-profit sector where resources are often contributed for specific purposes and management is accountable for the appropriate utilization of such resources. The objective of financial statements is to communicate information that is useful to investors, members, contributors, creditors and other users ("users") in making their resource allocation decisions and/or assessing management stewardship. Consequently, financial statements provide information about: C. (a) an entity's economic resources, obligations and equity / net assets; (b) changes in an entity's economic resources, obligations and equity / net assets; and (c) the economic performance of the entity. Qualitative Characteristics of Financial Statements2 Qualitative characteristics define and describe the attributes of information provided in financial statements that make that information useful to users. The four principal qualitative characteristics are understandability, relevance, reliability and comparability. Understandability For the information provided in financial statements to be useful, it must be capable of being understood by users. Users are assumed to have a reasonable understanding of business and economic activities and accounting, together with a willingness to study the information with reasonable diligence. 2 Ibid. 1.1.3 Relevance For the information provided in financial statements to be useful, it must be relevant to the decisions made by users. Information is relevant by its nature when it can influence the decisions of users by helping them evaluate the financial impact of past, present or future transactions and events or confirm, or correct, previous evaluations. Relevance is achieved through information that has predictive value or feedback value and by its timeliness. (a) Predictive value and feedback value Information that helps users to predict an entity's future income and cash flows has predictive value. Although information provided in financial statements will not normally be a prediction in itself, it may be useful in making predictions. The predictive value of the income statement, for example, is enhanced if abnormal items (i.e., those that are highly unusual and/or non-recurring) are separately disclosed. Information that confirms or corrects previous predictions has feedback value. Information often has both predictive value and feedback value. (b) Timeliness For information to be useful for decision making, it must be received by the decision maker before it loses its capacity to influence decisions. The usefulness of information for decision making declines as time elapses. Reliability For the information provided in financial statements to be useful, it must be reliable. Information is reliable when it is in agreement with the actual underlying transactions and events, the agreement is capable of independent verification and the information is reasonably free from error and bias. Reliability is achieved through representational faithfulness, verifiability and neutrality. Neutrality is affected by the use of conservatism in making judgments under conditions of uncertainty. (a) Representational faithfulness Representational faithfulness is achieved when transactions and events affecting the entity are presented in financial statements in a manner that is in agreement with the actual underlying transactions and events. Thus, transactions and events are accounted for and presented in a manner that conveys their substance rather than necessarily their legal or other form. The substance of transactions and events may not always be consistent with that apparent from their legal or other form. To determine the substance of a transaction or event, it may be necessary to consider a group of related transactions and events as a whole. The determination of the substance of a transaction or event will be a matter of professional judgment in the circumstances. 1.1.4 (b) Verifiability The financial statement representation of a transaction or event is verifiable if knowledgeable and independent observers would concur that it is in agreement with the actual underlying transaction or event with a reasonable degree of precision. Verifiability focuses on the correct application of a basis of measurement rather than its appropriateness. (c) Neutrality Information is neutral when it is free from bias that would lead users toward making decisions that are influenced by the way the information is measured or presented. Bias in measurement occurs when a measure tends to consistently overstate or understate the items being measured. In the selection of accounting principles, bias may occur when the selection is made with the interests of particular users or with particular economic or political objectives in mind. Financial statements that do not include everything necessary for faithful representation of transactions and events affecting the entity would be incomplete and, therefore, potentially biased. (d) Conservatism Use of conservatism in making judgments under conditions of uncertainty affects the neutrality of financial statements in an acceptable manner. When uncertainty exists, estimates of a conservative nature attempt to ensure that assets, revenues and gains are not overstated and, conversely, that liabilities, expenses and losses are not understated. However, conservatism does not encompass the deliberate understatement of assets, revenues and gains or the deliberate overstatement of liabilities, expenses and losses. Comparability Comparability is a characteristic of the relationship between two pieces of information rather than of a particular piece of information by itself. It enables users to identify similarities in and differences between the information provided by two sets of financial statements. Comparability is important when comparing the financial statements of two different entities and when comparing the financial statements of the same entity over two periods or at two different points in time. Comparability in the financial statements of an entity is enhanced when the same accounting policies are used consistently from period to period. Consistency helps prevent misconceptions that might result from the application of different accounting policies in different periods. When a change in accounting policy is deemed to be appropriate, disclosure of the effects of the change may be necessary to maintain comparability. 1.1.5 Qualitative characteristics trade-off In practice, a trade-off between qualitative characteristics is often necessary, particularly between relevance and reliability. Generally, the aim is to achieve an appropriate balance among the characteristics in order to meet the overall objectives of financial statements. The relative importance of the characteristics in different cases is a matter of professional judgment. D. GAAP and the Accrual Basis of Accounting Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“GAAP”) is a written body of guidelines and principles which govern the preparation of financial statements. Canadian GAAP is regulated by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA) while International GAAP (which the EU and most nations except for the USA and Japan subscribe to) is regulated by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB)3. GAAP, like the law, is constantly evolving. However, there is one overriding and constant principle that you must familiarize yourself with: Accrual Accounting. The cornerstone of accrual accounting is the notion that a transaction should be recorded in a company’s financial statements when something of economic substance occurs, regardless of whether or not there was an exchange of cash at the time of the transaction. Furthermore, because of the double-entry nature of accounting (the details of which are mechanical and not germane to your basic understanding of financial statements), the following equation must always be satisfied when a transaction is recorded: Assets = Liabilities + Equity The above equation, which is a key component to accrual accounting, is analogous to an individual that owns a house. The house in question is worth say $600,000. Also, let us assume that the outstanding mortgage on the house (a liability of the owner) is $350,000. Therefore, that individual’s ownership interest in the house (i.e., his/her “equity”) is $250,000 ($600,000 $350,000). Accordingly, as the amount of the mortgage is paid down, the owner’s equity in the house increases. Also, if the market value of the house (i.e., the left hand side of the equation) increases, then the owner’s equity also increases. Always remember that, whenever a transaction is recorded in the accounts of a company, the above noted equation must be satisfied. Two examples of common business transactions will help to illustrate this point: 3 As of January 1, 2011, all public companies in Canada will be required to prepare financial statements in accordance with IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) which is set by the IASB. However, most privately-held companies will have the option to adopt accounting standards designed specifically for private enterprises and which, for the most part, are modeled on Canadian standards that were in place prior to the introduction of IFRS. 1.1.6 Example #1 – Sale of goods on credit terms A customer walks into ABC Ltd. and purchases goods for $1,000. The customer asks that the purchase be placed on their account and that they will pay the outstanding balance in 45 days (as per the terms of the store’s credit policy). Under this scenario, a transaction of economic substance has occurred (i.e., the sale of goods and the customer’s promise to pay). Accordingly, ABC Ltd. is entitled under GAAP to record $1,000 worth of revenue on that day, even though the cash will not be received for another 45 days. Therefore, revenue (a component of equity) increases by $1,000 on the day of the transaction. But if no cash was received, how do we satisfy the above noted equation? In other words, if equity increases by $1,000, then either an asset has to increase by $1,000 or a liability has to decrease by $1,000. The answer is that, on the day of the sale, ABC Ltd. increases revenue/equity by $1,000 and it also records a corresponding increase in accounts receivable (an asset). When the cash is received from the customer 45 days later, ABC Ltd. will then increase its cash (an asset) by $1,000 and decrease its accounts receivable by the same amount. The point here is that revenue was recorded when a transaction of economic substance occurred and not when the cash payment was actually received. This concept is often referred to as the revenue recognition principle and it is a key tenet of accrual accounting. Example #2 – Purchase and use of equipment ABC Ltd. purchases a new cash register from a vendor for $1,000 on 90 days credit. Accordingly, on the day of the purchase ABC Ltd. records a $1,000 increase in equipment (an asset) and a corresponding increase in accounts payable (a liability). When it is time to pay, ABC Ltd. will decrease its cash by $1,000 and decrease its accounts payable by the same amount. However, that is not where this story ends. GAAP dictates that the cash register must be recorded as an asset on the date of purchase because it meets the definition of an asset (i.e., a resource controlled by an entity and which is likely to generate net cash flows in the future). However, the cash register does not have an indefinite useful life. Instead, management is of the opinion that the new cash register will be functional for 5 years before it becomes obsolete and will require replacement (in other words, the cash register is a depreciating asset). As a result of the foregoing, GAAP dictates that the acquisition price of $1,000 (which was initially recorded as an asset) should be amortized (i.e., recorded as an expense) during that five year period. While there are several methods to calculate amortization expense, a commonly used one is to amortize the asset evenly over its useful life4. In this case, ABC Ltd. would record amortization expense of $200 per year in respect of the cash register ($1,000 divided by 5 years). Accordingly, each year for the next five years, 4 Although there are a number of amortization methods allowed for financial reporting purposes (i.e., GAAP), for income tax purposes a business is required to amortize its depreciable assets in accordance with specific methods and rates as set out in the Income Tax Act. 1.1.7 ABC Ltd. will record a $200 increase in amortization expense (i.e., a decrease in equity5) and a $200 decrease in the value of equipment (an asset) recorded on its balance sheet, thereby satisfying the A = L + E equation. The key point with Example #2 is that accrual accounting does not record the purchase of the cash register as an expense on the date of purchase or even 90 days later (even though ABC Ltd. paid cash on that day). Rather, because the cash register is expected to help generate cash flows over a five year period, it will be amortized (i.e., expensed) over that period. This concept is often referred to as the: matching principle6. There are many more examples of the matching principle in practice (e.g. prepayment of a one year insurance policy such that 1/12 of the upfront cost is expensed in each month for the next 12 months). The use of accrual accounting does not suggest that the company’s actual cash flows are unimportant. On the contrary, there is an entire financial statement dedicated to informing the user about what happened to the company’s cash resources during the period in question (see Statement of Cash Flows in part E below). What the use of accrual accounting does suggest, however, is that the financial performance of a company should be measured on the basis of the economic substance of transactions and when they occur, instead of focusing solely on the timing of cash inflows and outflows. E. Financial Statements Note: Refer to Tab 5 for examples of items commonly found in the following statements. Balance Sheet A balance sheet is a financial statement which sets out the financial position of a company as at a specific point in time. It shows the company’s assets, its liabilities and the residual ownership interest known as shareholders’ equity (i.e., A = L + E). Shareholders’ equity is sometimes referred to as the “net assets” of the company. Income Statement An income statement sets out the net income (i.e., revenues less expenses) of a company’s operations for a particular period of time. In theory, an income statement can be produced for any period of time. Most income statements are prepared on a fiscal year basis (i.e., annually) for external reporting and tax compliance purposes. However, the management team of a company will typically generate an income statement at the end of each month and/or each quarter in order to track operating performance more frequently than once a year. 5 Remember that revenues and expenses are a component of equity. Therefore, an increase in revenues results in an increase to equity while an increase in expenses results in a decrease to equity. 6 In other words, expenses are recorded or “matched” against revenues in the period(s) in which those expenses were incurred in order to generate the related revenues. 1.1.8 Statement of Retained Earnings The statement of retained earnings is simply a statement of the changes in the retained earnings account for a period of time. In most cases, the only items affecting this account are the amount of net income (or loss) generated during the period less any dividends declared. Statement of Cash Flows The statement of cash flows summarizes the operating, financing and investing activities of a company and the effects of those activities on the company’s cash resources. In short, this statement shows all of the cash inflows and cash outflows of a company for a particular period of time. The statement of cash flows differs from an income statement as the income statement is based on accrual accounting (see part D above), which essentially ignores the timing of cash receipts/payments when recognizing a transaction. Notes to the Financial Statements The notes are normally located after the financial statements and provide certain additional information that is of importance to financial statement users. Notes may include, but are not necessarily limited to: A brief description of the company and its operations; A summary of significant accounting policies and accounting estimates employed by the company; Details regarding the company’s property and equipment; Details regarding the timing of debt repayments and any other commitments; and Details regarding the share structure of the company, including certain rights and restrictions attached to each class of share. 1.1.9 F. Other Accounting (GAAP) Concepts Historical Cost Principle Generally speaking, long term assets as property and equipment and investments in subsidiary companies are recorded in a company’s financial statements at their original cost (less any accumulated amortization expense in the case of depreciable assets7). Any increases in the value of the aforementioned assets subsequent to the acquisition date are not recorded in the financial statements8. The rationale for the use of the historical cost principle is that historical cost is easy to implement and also cost-effective in that asset appraisals are not required in order to determine an asset’s current value (i.e., market value). Furthermore, the historical cost of an asset is easily verifiable and therefore increases the reliability of financial statements. The primary drawback of the historical cost principle is that it reduces the relevance of financial statements, in particular for real estate holding companies. That is because the land owned by such companies would be recorded at its original purchase price9 and not its current market value. Accordingly, the historical cost of a property may bear no resemblance to its current value (especially if the property was acquired many years prior to the current balance sheet date). Going Concern Assumption The preparation of financial statements in accordance with GAAP assumes that the company in question will be able to realize its assets and discharge its liabilities in the normal course of operations. In practice, the foregoing statement is understood to mean that the company will be capable of sustaining business operations for at least one more operating cycle (i.e., one more fiscal year). Should this assumption not be appropriate (i.e., the company is no longer solvent), then ordinary GAAP would not apply and the balance sheet of the company would have to be prepared on a liquidation basis. 7 Depreciable assets are those assets whose utility diminishes over time. Most assets listed under property and equipment (except for land) are depreciable. 8 With the adoption of IFRS on January 1, 2011, certain companies can elect to record post-acquisition increases in the value of property and equipment (including real estate properties). However, most small and medium-sized enterprises in Canada are unlikely to adopt IFRS (due to high compliance costs) and will therefore continue to employ the historical cost principle. 9 As stated earlier, land is not subject to amortization. That is because land, in theory, has an indefinite useful life.