an evaluation of working capital policies and their impact on

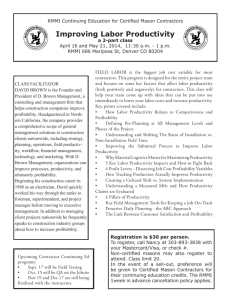

advertisement