28 chapter 3 theory and equations

advertisement

28

CHAPTER 3

THEORY AND EQUATIONS

29

3.1 INTRODUCTION

Throughout this work, kinetic data will be presented for the inhibition of an enzyme (PTP)

reaction with a substrate (pNPP) by a variety of inhibitors. In order to analyze the data, theoretical models

must be used to develop appropriate equations. This chapter presents the development of the models used

throughout this work. Section 3-2 will present the Michaelis-Menten model of enzyme interaction with

substrate; this is the theory that is presented in any textbook on enzyme kinetics.1 Section 3-3 will present

the modeling of the inhibition of an enzyme by reversible competitive and uncompetitive inhibitors. This is

also a review of material that is readily available in textbooks.1 The following sections will deal with

irreversible inhibition of an enzyme.

None of the scenarios presented herein have previously been

presented in the literature to the knowledge of this author. The systems that will be presented include:

3-4 Irreversible inactivation of an enzyme in the presence of substrate and a reversible inhibitor by

a species at equilibrium concentration.

3-5 Irreversible inactivation of an enzyme in the presence of substrate and reversible inhibitor by a

species whose concentration increases linearly with time.

3-6 Irreversible inactivation of an enzyme in the presence of substrate and reversible inhibitors by

the combination of a species at equilibrium concentration and a species whose concentration is

increasing linearly with time

3-7 Irreversible inactivation of an enzyme in the presence of substrate and reversible inhibitors by

a species whose concentration is decreasing over time due to reaction with a matrix component.

3.2 MICHAELIS-MENTEN KINETICS1

3.2.1 Derivation of equations

Michaelis-Menten kinetics relies on a general mechanism as shown in Scheme 3-1. In this system,

first, enzyme (E) interacts with substrate (S) reversibly to form an enzyme-substrate complex (ES). This

complex then reacts irreversibly to form a product (P) and free enzyme. The amount of free enzyme

present at any point in time will be equal to the initial concentration of enzyme [E0] minus the amount of

enzyme bound to the substrate [ES].

30

E + S

[E0]-[ES] [S]

k1

k2

E-S

k-1

E + P

[ES]

Scheme 3-1. Assumed mechanism for Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

The assumptions of Michaelis-Menten are that substrate is present in much greater concentration

than enzyme and that the ES complex will rapidly reach a steady-state, i.e. its rate of formation and rate of

consumption will be equal.

d[ES]

= k 1 [E ]∗ [S] − k −1 [ES] − k 2 [ES] = 0

dt

Solving for [ES] yields eq 3-1

[ES] =

k 1 [E ][S]

k −1 + k 2

eq 3-1

The Michaelis constant, Km, is defined by

Km =

(k −1 + k 2 )

k1

Substituting this into eq 3-1 produces eq 3-2

[ES] = [E][S]

eq 3-2

Km

eq 3-2 can be combined with

[E ] = [E 0 ] − [ES]

to yield eq 3-3

[ES] = [E 0 ][S]

K m + [S]

eq 3-3

The rate (ν) of the reaction (formation of product) can be expressed as

ν = k 2 [ES] =

k 2 [E 0 ][S]

K m + [S]

31

The form of this equation will be the same if the ES complex is converted to enzyme and product

in one step, as shown in Scheme 3-1, or in a multi-step process. For this reason k2 is usually replaced by k0,

the product of k2 and the rate constants for any subsequent steps. Another common substitution is the

replacement of k0[E0] with V0, the maximum velocity for the reaction. This yields the standard MichaelisMenten equation, which is shown in eq 3-4.

ν=

V0 [S]

K M + [S]

eq 3-4

If ν is graphed as a function of substrate concentration (shown in Figure 3-1), the result will be a

rectangular hyperbola that passes through the origin. It has asymptotes of V0 and -Km. When [S] << Km,

the function will be linear with respect to [S] and the rate equation takes on the properties of a second-order

rate law

ν=

V0 [S]

KM

At [S] >> Km, the reaction is essentially zero order in substrate, and the reaction is at its maximum velocity,

ν = V0 .

Slope=V0 / Km

ν = V0

[Substrate]

Figure 3-1. Hyperbolic relationship between velocity and [Substrate].

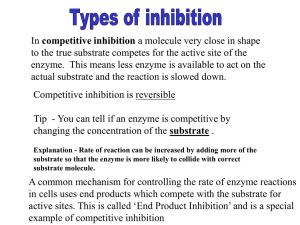

An inhibitor of the reaction between enzyme and substrate will affect this graph by either lowering

the asymptote (V0) or by decreasing the slope of the function in the linear region. An inhibitor that affects

only the slope in the linear region is called a competitive inhibitor. An inhibitor that affects only the

32

asymptote is called an uncompetitive inhibitor. A compound that affects both slope and asymptote is said

to display mixed inhibition. The equations for dealing with these cases are developed in section 3-3.

3.2.2 Experimental determination of V0 and Km

In order to determine V0 and Km for the reaction of a particular enzyme with its substrate, one

must measure the velocity at a variety of substrate concentrations. This data can then be fitted to eq 3-4 to

obtain the parameters of interest. Two popular methods of analysis are Lineweaver-Burk plots and Hanes

plots. The Lineweaver-Burk method involves taking the reciprocal of eq 3-4 to yield eq 3-5.

1 Km 1

1

=

∗

+

ν V0 [S] V0

eq 3-5

A plot of ν -1 versus [S]-1 should be linear. A linear regression can be performed. and the slope and the

intercept can be manipulated algebraically to determine Km and V0. This is the most popular method in the

literature, but is considered to be of dubious quality because it gives a false impression of experimental

error by minimizing the appearance but not the reality of scatter in the data. Another less popular but more

highly regarded technique uses Hanes plots. In a Hanes analysis eq 3-5 has been multiplied through by [S]

to yield eq 3-6.

[S] = K m

ν

V0

+

1

∗ [S]

V0

eq 3-6

Again a linear regression can be performed for the plot of [S]/ν versus [S] and the slope and intercept

manipulated to yield Km and V0.

3.3 REVERSIBLE INHIBITION OF AN ENZYME1

3.3.1 Derivation of equations

A compound that slows down the reaction of enzyme and substrate in a time-independent manner

is said to be a reversible inhibitor of that enzyme. If the inhibitor binding to the enzyme prevents the

enzyme from reacting with substrate, the inhibition is said to be competitive. This is shown in Scheme 3-2

as the top pathway. If the inhibitor binds to the ES complex preventing the ES complex from forming

33

product, the inhibition is called uncompetitive. An inhibitor that both interferes with formation of the ES

complex and conversion of that complex to product is said to be a mixed inhibitor.

E-Ic

Competitive Inhibition

Ki,c

Ic

k1 S

E

k0

E-S

k-1

Ki,u

E+P

Iu

Uncompetitive Inhibition

E-Iu-S

Scheme 3-2. Competitive and uncompetitive reversible inhibition of an enzyme.

E = Enzyme; S = Substrate; Ic = Competitive Inhibitor, Iu = Uncompetitive Inhibitor.

Here the total amount of enzyme (E0) added will be distributed among the differing species

[E 0 ]

=

[E] + [ES] + [EI c ] + [EI u S]

eq 3-7

Equilibria assumptions can be made for E-Ic and E-Iu-S

[EI c ]

=

[E][I c ]

K i, c

and

[EI u S]

=

[ES][I u ]

K i, u

It is still valid to assume that E-S is at a steady state concentration and thus eq 3-2 still applies. Combining

eq 3-2 and eq 3-7 with the equilibria for [EIc] and [EIuS] leads to the rate expressed as eq 3-8.

[S]

1 + [I u ]

K i , u

V0 [S]

=

ν = k 0 [ES] =

[I ]

[I ]

1 + [I c ]

K m 1 + c + [S] 1 + u

K i, c

K i, u

K i, c

Km

+ [S]

[

]

I

u

1 +

K i , u

V0

eq 3-8

This is frequently given in terms of apparent values (V0, app and Km, app) that are defined by eq 3-9 and eq 310.

34

V0 ,app =

K m, app

V0

eq 3-9

[ ]

1 + I u

K

i, u

[I ]

1 + c

K

i, c

= Km

[I ]

1 + u

K

i, u

eq 3-10

These substitutions transform eq 3-6 into a form analogous to eq 3-4 as shown in eq 3-11.

ν=

V0, app [S]

K m ,app + [S]

eq 3-11

While these equations are derived assuming both competitive and uncompetitive modes of inhibition are

present, they can easily be modified for the special cases when only one or the other is present. Setting [Iu]

equal to zero will yield the correct equations when only competitive inhibition is present. Similarly, setting

[Ic] equal to zero will yield the appropriate equations when only uncompetitive inhibition is present.

3.3.2 Experimental determination of the type of reversible inhibition and its dissociation constant

In order to determine the mode by which an inhibitor interacts with an enzyme, as well as its

dissociation constant(s) Ki,c and/or Ki,u, one must measure velocity at several substrate concentrations for

each of several inhibitor concentrations.

The resulting data can be analyzed using the methods of

Lineweaver-Burk, Hanes, or Dixon (vida supra).

For the Lineweaver-Burk analysis, each series of

different substrate concentrations for a particular inhibitor concentration is analyzed using eq 3-5 (the

reciprocal of eq 3-11) to determine Km, app and V0, app. Those values are then analyzed using eq 3-9 and 3-10

to determine Ki,c and Ki,u. A Hanes analysis is done the same way except using eq 3-6 to determine Km, app

and V0, app.

For a Dixon analysis, two types of plots are used. In the first, velocity is plotted as a function of

[I] according to eq 3-12 (the reciprocal of eq 3-8)

[I ] 1 + [I u ]

K

1

= m 1 + c +

ν V0 [S] K i ,c V0 V0 K i ,u

eq 3-12

35

Using this method to analyze data gives immediate visual information about the presence or absence of

competitive inhibition.

If competitive inhibition is absent, then the lines corresponding to different

substrate concentration will be parallel {with a slope of 1/(V0Ki,u)}. If competitive inhibition is present,

then these lines will intersect at a single point, where x = -Ki, c.

In the second type of Dixon plot the product [S]ν-1 is plotted versus [I] according to eq 3-13

(obtained by multiplying eq 3-12 through by [S]).

[S] = K m

ν

V0

[I ]

[I u ]

1 + c + [S] 1 +

V

K

V

i ,c

0 K i ,u

0

eq 3-13

This graph gives immediate visual information about the presence or absence of uncompetitive inhibition.

If uncompetitive inhibition is absent, then the lines corresponding to different substrate concentrations will

be parallel {with a slope of Km/(V0Ki,c)}. If uncompetitive inhibition is present, then these line intersect at

a single point where x= -Ki, u.

3.4 IRREVERSIBLE INACTIVATION OF AN ENZYME IN THE PRESENCE OF SUBSTRATE AND

A REVERSIBLE INHIBITOR BY A SPECIES AT EQUILIBRIUM CONCENTRATION

3.4.1 Derivation of equations

If an inhibitor reacts with an enzyme in such a way that the velocity of the enzyme’s reaction with

substrate does not remain constant with time but instead decreases with time, then a model must be

developed for the time-dependent behavior of the enzyme. One such model is shown in Scheme 3-3. Here

once the E-I complex is formed, it goes on to irreversibly inactivate the enzyme.

In addition to I

irreversibly inhibiting the enzyme, Scheme 3-3 accounts for the presence of a reversible inhibitor labeled

here as V.2 Many groups have studied enzyme inactivation using a reaction model proposed by Kitz and

Wilson,3 where the enzyme inactivation is kept separate from enzyme interaction with substrate. There

have also been several studies that included enzyme inactivation in the presence of either substrate4 or a

reversible inhibitor.5 However, to date there has been no published treatment of these complications

occurring simultaneously.

36

k0

E-S

S

k1

E-V

k-1

E

Kv

E+P

V

I

Ki

E-I

kinact

E*

Scheme 3-3. Irreversible inhibition of an enzyme in the presence of substrate and a reversible inhibitor.

The first assumption of this treatment is that the concentrations of all enzyme-containing species in the

solution add up to the original enzyme concentration (eq 3-14).

[E 0 ] = [E] + [ES] + [EV] + [EI] + [E *]

eq 3-14

It is again assumed that the concentration of ES is at a steady state and thus eq 3-2 is valid. It is also

assumed that Kv and Ki are equilibrium constants

KV =

[E][V]

[EV]

Ki =

[E ][I]

[EI]

Considering this, the rate of production of inactive enzyme, E*, will be

[E][I]

d[E *]

= k inact [EI] =

Ki

dt

Using equilibria assumptions, eq 3-2 and eq 3-14, this can be rewritten as

d[E *]

= k inact [E I] = k inact

dt

[E 0 ] − [E *]

[S] + [V] + [I]

1 +

Km KV Ki

Ki

To integrate this, the variables are separated to give

k inact [I]

d[E *]

=

dt

{[E 0 ] − [E *]} [S] [V] [I]

1 +

+

+

Ki

K m K V K i

If E* = 0 at t = 0, this integrates to

[I]

37

− ln

{[E 0 ] − [E *]}

[E 0 ]

=

k inact [I]

[S] + [V] + [I] K

1 +

i

K m K V K i

t

Solving for E* yields

[E *]

k inact [I ]

−

t

[S ] + [V ] + [I ] ∗ K

1 +

i

K

K

K

m

V

i

= [E 0 ]1 − e

This can be used to find an expression for the rate of product formation.

d[P]

dt

=

k 0 [E ][S]

⇒

Km

k inact [I ]

−

t

[

S]

V ] [I ]

[

1 +

Ki

+

+

K

K

K

m

V

i

[E 0 ] − [E 0 ] ∗ 1 − e

[

E 0 ] − [E *]

k

[

S

]

d[P] k 0 [S]

= 0 ∗

=

∗

S]

[

V] [I]

[

S]

[

V ] [I]

[

dt

Km

Km

+

+

1+

+

+

1 +

K m K V K i

Km KV Ki

This simplifies to

k inact [ I ]

−

[

[V ] + [I ] K

S]

1+

+

i

Km

K V K i

d[P] k 0 [S][E 0 ] ∗ e

=

dt

[S] + [V] + [I]

K m 1 +

K m K V K i

t

Separating variables and integrating (assuming that [P]=0 at t=0) leads to eq 3-15.

k inact [I ]

−

t

[S ] + [V ] + [I ] ∗ K

+

1

i

k 0 [S] [E 0 ]K i

K

K

K

[P] =

1− e m V i

K m kinact [I]

eq 3-15

38

While this derivation deals with a single irreversible inhibitor, the treatment can be extended to multiple

inhibitors by making the substitution

k inact [I ]

=

Ki

∑

k inact j [I]j

Kij

j

3.4.2 Experimental determination of kinact and Ki

If a continuous assay is used to monitor the product formation as a function of time, then the

product formation can be fitted using non-linear, least-squares techniques to eq 3-16, which is a generic

form of eq 3-15.6,7 The m1 term is defined in eq 3-18 and the m2 term in eq 3-17. The m3 term in this

equation is an adjustment for the difficulty in determining the zero time when solutions are mixed.8

[P] =

(

m1 1 − e − m2 t + m3

)

eq 3-16

A range of values for m2 can be obtained by fitting several sets of data with a range of inhibitor

concentrations to eq 3-16. The parameters kinact and Ki (or a combination thereof) can be obtained by

analyzing the relationship between m2 and [I]. If there is only a single irreversible inhibitor (I) present,

then

m2 =

k inact [I]

eq 3-17

[S] + [V] + [I] K

1 +

i

K

K V K i

m

Taking the reciprocal of both sides yields

[S] + [V]

1 +

K

KV

1

m

=

m2

k inact [I]

Ki

+

1

k inact

A plot of m2-1 versus [I]–1 should be a straight line and the values of kinact and Ki can be obtained from the

intercept and slope of that line (assuming that [S], [V], Km and Kv are independently known).

k inact =

Ki =

1

Intercept ( m

−1

2

vs [I ]

−1

)

Slope (m −1 vs [I ]−1 )

1

2

*

Intercept (m −1 vs [I ]−1 )

[

S

]

[V]

2

1 +

+

Km KV

39

The separation of the values of kinact and Ki is contingent on some of the experiments being carried

out under conditions where [I] is saturating. This is not always experimentally viable or desirable. Under

non-saturating conditions where

1+

[S]

Km

+

[V] >> [I]

KV

Ki

eq 3-17 becomes

m2 ≈

k inact [I]

[S] + [V]

1 +

Km KV

Ki

A plot of m2 versus [I] will be linear with a zero intercept. In this case the ratio (kinact/Ki) can be obtained

but not their separate values

k inact

[S] + [V]

= Slope (m 2 vs [I ]) * 1 +

Ki

Km K V

The ratio (kinact/Ki) can also be determined/verified by plotting m1 versus [I]-1 according to

m1 =

k 0 [S] [E 0 ]K i

K m k inact [I]

eq 3-18

The line should have a zero intercept and its slope can be manipulated to find kinact/Ki.

k inact

k 0 [S] [E 0 ]

=

Ki

K m ∗ Slope(m vs [I ]−1 )

1

3.4.3 Experimental determination of inactivation parameters for a special case of Scheme 3-3 in

which the irreversible inhibitor (I) is in equilibrium with the reversible inhibitor (V)

A special case of the reactions in Scheme 3-3 involves [I] being in equilibrium with the reversible

inhibitor [V] and another species [L].

αV+ βL

KVL

I

The equilibrium constant for the new reaction is eq 3-19.

K VL =

[I]

[V] [L]β

α

eq 3-19

40

An additional assumption is that the concentration of [I] is sufficiently low that [V] and [L] are unchanged

by the reaction. With this new complicating factor, two types of continuous assay experiments should be

done: one with [V] held constant and [L] varied, and one with [L] held constant and [V] varied.

The reactions can still be fit to eq 3-16. However, now the analysis of m1 and m2 must address the

values of α and β. Combining eq 3-17 with 3-19 and taking reciprocals leads to

[S] + [V] K

[S] K

1 +

1 +

i

i

K

K

K

Ki

1

1

1

m

V

m

+

+

+

=

=

α

β

α

β

α −1

β

m2

k

k

k inact K VL [V] [L ]

k inact K VL [V ] [L]

K V k inact K VL [V ] [L]

inact

inact

For a series of experiments in which [L] is varied, m2-1 should be treated as a function of [L]−β. To

determine β, comparisons can be made by assuming different values of β and examining the resulting lines,

(keeping in mind the possibility of multiple inhibitors) i.e. m2-1 versus [L]-1; m2-1 versus [L]-2; etc. If there

is only a single inhibitor present, then the slope and intercept of a plot of m2-1 versus [L]−β can be

manipulated to determine the kinetic parameters. The value(s) of α are experimentally determined by

varying [V].

k inact =

1

Intercept m −1 vs [L ]−β

2

Slope m −1 vs [L ]−β

Ki

[V]α

2

=

*

K VL

Intercept m −1 vs [L ]−β

[S] + [V]

2

1 +

Km KV

In should be noted that determination of α may be a little more involved than that of β. In the event that

α=1, there is a linear relationship between m2-1 and [V] –1. But for α > 1, m2-1 is not linear in [V]–α , but is a

function of

[V]–α and [V]-(α-1).

Τhe relative coefficients of these terms are a function of the

kinetic/equilibrium parameters.

Another fact that may aid in determining α and β is that if the experiment is performed under nonsaturating conditions defined by

1+

[S]

Km

+

[V] >> K VL [V]α [L]β

KV

Ki

41

then a plot of ln(m2) versus ln[L] will have a slope of β. A plot of ln(m2) versus ln[V] will have a slope of

α, if α=1. For other values of α, this technique is not applicable to m2. The natural logarithm method can

be used to determine α and β from the m1 data since m1 is defined by

m1 =

k 0 [S] [E 0 ]K i

K m k inact K VL [V ]α ∗ [L]β

A plot of ln (m1) versus ln[L] will have a slope of –β , and a plot of ln(m1) versus ln[V] will have a slope of

–α. The m1 data can also be used to calculate the ratio Ki/kinact/KVL. There are many special cases that can

be considered with different numbers of inhibitory species and different values of α and β. The particular

example of two inhibitory species, one with α=2 and β=1 and the other with α =2 and β =2, is addressed in

detail in Appendix B of this work. (This is the observed mode for the ligand 2-amino-4-nitrophenol

discussed in Chapter 6.)

3.5 IRREVERSIBLE INACTIVATION OF AN ENZYME IN THE PRESENCE OF SUBSTRATE AND

REVERSIBLE INHIBITOR BY A SPECIES WHOSE CONCENTRATION INCREASES LINEARLY

WITH TIME

3.5.1 Derivation of equations assuming saturation conditions

In the last section, the time-dependent enzyme inactivation by a species whose concentration was

unchanging was considered. In this section the inclusion of a second time-dependent process will be

considered. This is a reaction in which the inhibitor is being produced at a rate comparable to that of the

enzyme’s inactivation. A model of this is shown in Scheme 3-4. Here the inhibitor [I] is not in equilibrium

with V and L, but has a concentration that is increasing linearly with time.

42

E-V

V

Kv

k1 S

E

E+P

k-1

kVL

αV + βL

k0

E-S

I

Ki

E-I

kinact

E*

Scheme 3-4. Inactivation of an enzyme by a species whose concentration is increasing linearly with time.

The assumptions for this treatment include that the sum of the concentration of the enzyme containing

species will equal the amount of enzyme added, [E0], as in eq 3-20.

[E 0 ] = [E] + [ES] + [E V] + [E I] + [E *]

eq 3-20

Also assumed are the expressions for the equilibria reactions.

KV =

[E][V]

[E V]

KI =

[E][I]

[E I]

It is assumed that [ES] is at a steady-state concentration such that eq 3-2 applies. The rate of formation of I

(assuming negligible consumption of I) can be expressed by

d[I]

α

β

= k VL [V ] [L]

dt

Separating variables and integrating (assuming that [I]=0 at time equals zero) yields

[I]

= k VL [V] [L] t

α

β

The rate of enzyme inactivation will be

d[E *]

dt

= k inact

[E] ∗ [I] = k

Ki

[E] ∗

inact

k VL [V ]α [L ]β t

Ki

Combining this with eq 3-20 and the equilibria assumptions leads to eq 3-21.

d[E *]

dt

1+

= k inact

[E 0 ] − [E *]

[S] + [V] + k VL [V]α [L]β t

Km

KV

Ki

Ki

∗ k VL [V ]α [L]β t

eq 3-21

43

Separating variables and integrating (assuming [E*]=0 at t=0) leads to eq 3-22.

[S] + [V] + k VL [V]α [L]β t − k t

ln[E ] = ln [E 0 ] − ln 1 +

inact

Km KV

Ki

[S] + [V]

k inact t 1 +

α

β

Km KV

k VL [V] [L ]

t

ln1 +

+

α

β

k VL [V ] [L ]

1 + [S] + [V ] K

i

K m K V

Ki

eq 3-22

The expression for the rate of product formation will be

k [E ][S]

d[P]

= k 0 [ES] = 0

dt

Km

Taking the natural logarithm of this and substituting eq 3-22 leads to eq 3-23.

k [E ][S]

[S] + [V] + k VL [V]α [L]β t − k t

d[P ]

− ln 1 +

ln

= ln 2 0

inact

Km KV

Ki

dt

Km

[S] + [V]

k inact t 1 +

α

β

Km KV

k VL [V ] [L ]

ln1 +

t

+

α

β

k VL [V] [L ]

1 + [S] + [V] K

i

K m K V

Ki

eq 3-23

3.5.2 Derivation of equations assuming non-saturation conditions

Due to the unwieldy nature of eq 3-23, it is useful to carry out experiments where the enzyme is

never saturated with inhibitor, such that

1+

[S]

Km

+

[V] >> k VL [V]α [L]β t

KV

Ki

In this case, eq 3-21 simplifies to

d[E *]

= k inact [EI] = k inact

dt

[E 0 ] − [E *]

[S] + [V]

1+

Km

∗ k VL [V ] [L ] t

KV

Ki

α

β

44

Now, separating variables, integrating (assuming [E*]=0 at t=0) and rearranging leads to

k inact k VL [V ] [L ] t 2

[S ] + [V ]

2Ki

1+

Km KV

α

[E ]

=

[E 0 ]

∗e

[S] + [V]

1 +

Km

β

K V

Combining this with eq 3-2 yields eq 3-24.

d[P]

=

dt

k 0 [E 0 ][S]

[S] + [V]

K m 1 +

K m K V

*e

k inact k VL [V ]α [L ]β t 2

[S ] [V ]

2K i

1+

+

Km KV

eq 3-24

This equation cannot be further integrated to find an equation for [P] at time (t) because exp(t2) is not

integrable by theoretical means.

3.5.3 Experimental determination of kinetic parameters

To investigate a system where the concentration of an enzyme inactivator is increasing linearly

with time over the course of the reaction, one can use continuous assays to monitor the product formation.

These experiments should be done for a series of [L] at constant [V] and a series of [V] at constant [L].

Neither the general case of 3.5.1 nor the special case of 3.5.2 led to a simple expression for [P] as a

function of time. Thus to analyze this data, the velocity, dP/dt, at each data point must be calculated and

used instead. This can be done using the Savitsky-Golay algorithm.9 In theory, the natural logarithm of the

velocity can be fitted by a graphing program such as Kaleidagraph to a generic form of eq 3-23.

m4 *m2

m

d[P ]

ln(ν ) = ln

ln 1 + 2

= m 1 − ln(m 2 + m 3 t ) − m 4 t +

dt

m

m3

3

t

However, in practice the values of m3 were poorly defined; their errors were on the same or larger order of

magnitude as their values. Since m3 contains all the information about the equilibrium constants, this

method of analysis could not satisfactorily be applied to determine the parameters of interest.

Analyzing the data assuming non-saturating conditions proved more successful. In this case

velocity data could be fit using eq 3-25, a generic form of eq 3-24.10

ν

= m1 * e −m 2 t

2

eq 3-25.

45

An analysis of m2 yields information about α, β and the kinetic parameters

k inact k VL [V ] [L ]

2K i

[S] + [V]

1 +

K

KV

m

α

m2 =

β

A graph of m2 versus [L]β should be linear and have a zero intercept. The slope of this plot can be

manipulated to derive a ratio of the kinetic and equilibrium parameters. β can be found by trial and error or

by graphing ln(m2) versus ln [L], where the slope equals β.

k inact k VL

Ki

[S] + [V]

21 +

Km KV

= Slope (m vs [L ]β )∗

2

[V]α

An analysis of the variation in m2 as [V] is changed can similarly be used to determine α, which can be

used in the above equation.

3.6 IRREVERSIBLE INACTIVATION OF AN ENZYME IN THE PRESENCE OF SUBSTRATE AND

REVERSIBLE INHIBITORS BY THE COMBINATION OF A SPECIES AT EQUILIBRIUM

CONCENTRATION AND A SPECIES WHOSE CONCENTRATION IS INCREASING LINEARLY

WITH TIME

3.6.1 Derivation of equations

In the last two sections, cases were considered where a) a species at a constant concentration was

inactivating an enzyme, and b) a species whose concentration is linearly increasing with time is inactivating

the enzyme. In combination, these two modes give Scheme 3-5.

46

αV + βL

kVL

E-V

V

Kv

k1 S

I

E

E-I

E-S

E*

E+P

k-1

Ki

kinact

k0

K'i

I'

KVL

γV + δL

E-I'

k'inact

E*

Scheme 3-5. Simultaneous inactivation of an enzyme by both a species at constant

concentration and one whose concentration increases with time

To analyze this case, the assumptions from the last two sections are combined. The sum of the

concentrations of all the enzyme-containing species is assumed to add up to the amount of enzyme added,

[E0].

[E 0 ] = [E] + [ES] + [EV] + [EI] + [EI'] + [E *]

The previously stated equilibrium assumptions are assumed to hold as well as is the steady-state

assumption on [ES] (eq 3-2).

Combining the assumptions and information derived in the last two sections and neglecting the

Michaelis-Menten complex for the inhibitor whose concentration increases linearly with time leads to

d[E *]

dt

[E0 ] − [E *]

=

S

[ ] + [V] + [V]γ [L]δ

1 +

Km KV

K ' I K VL

α

β

γ

δ

k' [V] [L ]

k inact k VL [V ] [L] t

+ inact

∗

KI

K ' I K VL

Separating variables and integrating (assuming [E*]=0 at time t=0) leads to

− ln

[E0 ] − [E *]

[E0 ]

1

=

[

S] [V] [V]γ [L]δ

1 +

+

+

Km KV

K' I K VL

α

β 2

γ

δ

k'inact [V] [L] t

k inact ∗ k VL [V] [L] t

∗

+

2K I

K 'I K VL

47

Converting this to velocity yields eq 3-26.

d[P]

dt

k 0 [S][E 0 ]

=

[S] + [V] + [V]γ [L]δ

1 +

K

m

Km KV

K' I K VL

k inact ∗ k VL [V ]α [L ]β t 2

−

[S ] [V ] [V ]γ [L ]δ

*

e

2KI 1 +

+

+

K m K V K 'I K VL

+

γ

δ

[

]

[

]

[

]

[

]

S

V

V

L

K' K 1 +

+

I VL

K m K V K 'I K VL

k 'inact [V ]γ [L ]δ t

eq 3-26

3.6.2 Experimental determination of kinetic parameters

As described in the earlier sections, continuous assay experiments can be performed and the data

used to calculate velocity as a function of time. The velocity can thus be fit to eq 3-27, a generic form of eq

3-26.11

ν=

2

d[P ]

= m1 * e − m 2 t − m 3 t

dt

eq 3-27

The fit parameters m1, m2, and m3 can be used to calculate α, β, γ, δ and the ratios of the kinetic and

equilibrium parameters. For an application of this example, see Section 6.2.3.2 of this work.

3.7 IRREVERSIBLE INACTIVATION OF AN ENZYME IN THE PRESENCE OF SUBSTRATE AND

REVERSIBLE INHIBITORS BY A SPECIES WHOSE CONCENTRATION IS DECREASING OVER

TIME DUE TO REACTION WITH A MATRIX COMPONENT.

3.7.1 Derivation of equations

Sometimes the study of enzyme inactivation kinetics is complicated by a side reaction between the

inhibitor and a matrix component. This can lead to depletion of the concentration of the inhibitor over the

course of the experiment. For example, quinones have been known to inactivate enzymes with active site

thiols and also to react with thiols in the matrix. Scheme 3-6 depicts such a series of reactions. The

irreversible inhibitor is depicted as Q (for quinone) and the matrix component as M (for Mercaptoethanol).

These labels are merely to allow easy usage when these equations come into play in Chapter 7.

48

k0

E+P

E-S

k1

k-1

S

E

KQ

kQM

M

Q

E-Q

Q*

kinact

E*

Scheme 3-6. Inactivation of an enzyme by a species whose concentration is

depleted by reactions with a matrix component.

If Q0 is the total amount of Q added, then

[Q 0 ] = [Q] + [Q *]

If M0>>Q0 then [M]t ≈ M0 and

d[Q *]

= k QM [Q][M ]0 = k QM {[Q 0 ] − [Q *]} ∗ [M ]0

dt

Separating variables and integrating (assuming Q*=0 at t=0) leads to the following expression for [Q].

[Q] = [Q 0 ]∗ e − k

QM

[M ]0 t

The rate of enzyme deactivation can be expressed by

[E][Q] = k [E][Q 0 ] ∗ e

d[E *]

= k inact [EQ] = k inact

inact

KQ

dt

KQ

− k QM [M ]0 t

Implementing the conservation of enzyme and equilibria assumptions gives eq 3-28.

d[E *]

=

dt

k inact

[E 0 ] − [E *]

− k QM [M ]0 t

1 + [S] + [Q 0 ]∗ e

Km

KQ

KQ

− k QM [M ]0 t

∗ [Q 0 ]∗ e

eq 3-28

Separating variables and integrating (assuming E*=0 at t=0) leads to

[S] + [Q 0 ]∗ e

ln [E] = ln[E 0 ] − ln1 +

K

KQ

m

− k QM [M ]0 t

[S] + [Q 0 ] ∗ e kQM [M ]0 t

1 +

Km

Ki

− k inact ∗ ln

k QM [M ]0

S

[

] + [Q0 ]

1+

Km KQ

49

This can be used to find an expression for ln(ν) as in eq 3-30.

[S][E 0 ] − ln1 + [S] + [Q 0 ]∗ e

ln(ν) = ln k 0 *

K m

Km

KQ

− k QM [M ]0 t

[S] + [Q 0 ] ∗ e kQM [M ]0 t

1 +

Km KQ

− k inact

∗ ln

k

[S] + [Q0 ]

Q − M [M ]0

1+

Km KQ

eq 3-30

Due to the unwieldy nature of this equation, it is worthwhile to consider a reaction under non-saturating

conditions, where

[S] >> [Q0 ]

Km

KQ

1+

This additional assumption gives

d[E *]

=

dt

k inact {[E 0 ] − [E *]}[Q 0 ] − k QM [M ]0 t

∗e

[S] K

1 +

Q

K m

Separating variables and integrating (assuming [E*]=0 at t=0) yields

k inact

[S] −

−k

[M ] t

ln [E ] = ln[E 0 ] − ln1 +

∗ [Q 0 ] ∗ 1 − e QM 0

K

[

S

]

m

K Q k QM [M ]0

1 +

K m

(

)

Using this to find reaction velocity yields eq 3-31

ln(ν) = ln

k 2 [E 0 ][S]

[S]

K m 1 +

K m

−

k inact

[S] K k [M]

1 +

Q QM

0

K m

(

∗ [Q 0 ] ∗ 1 − e

− k QM [M ]0 t

)

eq 3-31

3.7.2 Experimental determination of kinetic parameters

Eq 3-30 can be expressed in generic form as

m + m 3 ∗ e m 4t

ln(ν ) = m 1 − ln m 2 + m 3 ∗ e − m 4 t − m 5 ∗ ln 2

m 2 + m3

(

)

This form proved difficult to use in Kaleidagraph; attempts to use it to fit real data always aborted due to

singular coefficient matrices. On the other hand eq 3-31 can be expressed generically as eq 3-32.

(

ln(ν) = m1 − m 2 ∗ 1 − e − m 3t

)

eq 3-32

50

Using eq 3-32, m3 should stay constant as long as [M]t remains constant. If m3 varies, specifically if it

decreases as [Q] increases, that implies that the concentration of M is being diminished over the course of

the experiment and [M]t ≠ M0. In addition, m1 should remain constant as long as [S] is not varied. If m1

decreases as [Q] increases then, the assumption of a negligible contribution of the [E-Q] complex will be

proven invalid.

51

3.8 REFERENCES AND ENDNOTES

1. Cornish-Bowden, A. Enzyme Kinetics, Portland Press: Cambridge, 1995.

2. The V is for vanadate, the reversible inhibitor that will be used throughout this work.

3. Kitz, R.; Wilson, I.B. J. Biol. Chem. 1962, 237, 3245-3249. Esters of Methanesulfonic Acid as

Irreversible Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase.

4. a)Tsou, C.L. Adv. In Enz. 1988, 61, 381-436. Kinetics of Substrate Reaction During Irreversible

Modification of Enzyme Activity. b) Wakselman, M.; Xie, J.; Mazaleyrat, M.R.; Boggetto, N.; Vilain,

A.-C.; Montagne, J.-J.; Reboud-Ravaux, M. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 1539-1547. New MechanismBased Inactivators of Trypsin-like Proteases. Selective Inactivation of Urokinase by Functionalized

Cyclopeptides Incorporating a Sulfoniomethyl-Substituted m-Aminobenzoic Acid residue. c)Wolf,

B.B.; Vasudevan, J.; Gonias, S.L. Biochem. 1993, 32, 1875-1882. Reaction of Nerve Growth Factor γ

and 7S Nerve Growth factor Complex with Human and Murine α2-Macroglobin.

5. a)Langeland, B.T.; McKinley-McKee, J.S. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994, 308, 367-373. Inhibition and

Inactivation of Horse Liver Alcohol Dehydrogenase with the Imidazobenzodiazepine Ro 15-4513.

b)Labrou, N.E.; Clonis, Y.D. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995, 321, 61-70. Oxaloacetate Decarboxylase:

On the Mode of Interaction with Substrate-Mimetic Affinity Ligands

6. As a test on the accuracy of this model, velocities can be calculated and fit to ( ν = −m1m2e− m 2 t ) and the

values of m1 and m2 compared to those obtained using eq 3-16.

7. The notation is chosen to be consistent with the general curve fit option of Kaleidagraph 3.08 by

Synergy Software.

8. In using this model to analyze data, the mixing time (m3) was usually <1 second, which was well below

the sampling interval of 6 seconds.

9. Annino, R.; Driver, R. Scientific and Engineering Applications with Personal Computers; John Wiley

and Sons: New York, 1986.

10. As a test on the accuracy of this model, ln(ν) can be calculated and fit to { ln (ν ) = ln (m1 ) − m 2 t 2 } and the

values of m1 and m2 compared to those obtained using eq 3-25.

11. As a test on the accuracy of this model, ln(ν) can be calculated and fit to { ln (ν ) = ln (m1 ) − m 2 t 2 − m3 t } and

the values of m1, m2 and m3 compared to those obtained using eq 3-27.