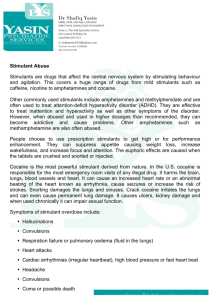

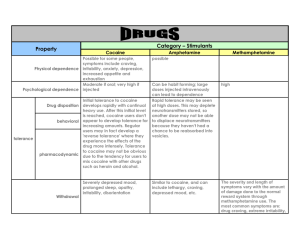

The levels of use of opioids, amphetamines and cocaine and

advertisement