- Royal Australian Navy

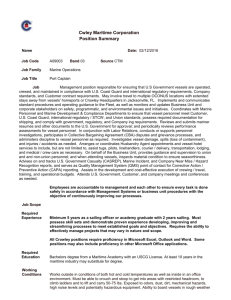

advertisement