Western Union in 2008: Send Me the Money

advertisement

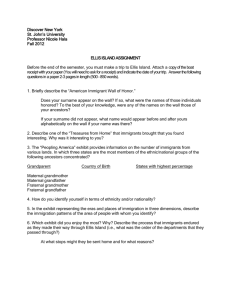

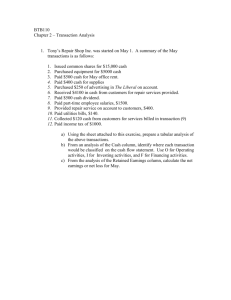

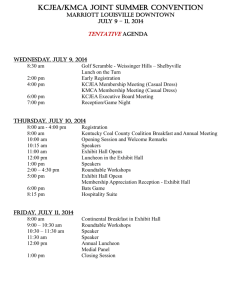

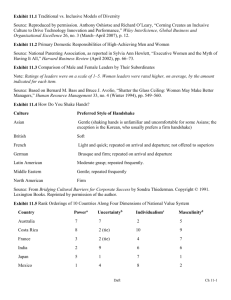

ETHICS PRESENTED BY WESTERN UNION IN 2008: SEND ME THE MONEY! Disclaimer: This case was prepared by Armand Gilinsky, Jr., Professor of Business at Sonoma State University, from published sources, as a basis for class discussion, not to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. PRESENTED BY: WESTERN UNION IN 2008: SEND ME THE MONEY! When Jorge Ochoa, Vice President of Finance, and Raul Duany, Director of Corporate Communications joined The Western Union Company (WU) in November 2008, both were cautiously optimistic about the company’s future prospects in the global money transfer market. The primary customers for global money transfers, immigrants, flowed from poorer to wealthier countries, seeking better opportunities. When immigrants left their home countries, they often left behind family members who depended upon them for financial support. To send money back home, immigrants most often used money transmitters like WU. Founded in 1851, WU had formerly enjoyed a long history as a telegraph and wire services company, but by 2006 it had discontinued its telegraph services to focus exclusively on money transfers. Its money transfer business had grown 13 percent during the third quarter of 2008, despite slowing growth in certain areas of the world. Declining growth in China, parts of Europe, and the critical U.S.-Mexico corridor offset rising transaction volumes in India and the Philippines. On November 10, 2008, Ochoa and Duany were summoned to WU company headquarters in Englewood, Colorado for a breakfast meeting with company President and CEO, Christina Gold. Her new executives’ first assignment was to help develop a strategy for WU that would mitigate any impact of further erosion of its primary money transfer business, while remaining mindful of the need to address company’s critics regarding its commitment to social responsibility. Before joining WU, Ochoa and Duany were well aware that government regulators and shareholder activists were actively scrutinizing the operations and fee-charging practices of money transfer businesses. A shareholder initiative calling on WU to become a 1|Page PRESENTED BY: better corporate citizen and donor was released to the press on April 25, 2008, prior to Western Union’s annual shareholder meeting in June (see Exhibit 1 for the transcript of the shareholder initiative). From summer 2007 to summer 2008, a consumer activist organization known as the Transnational Institute for Grassroots Research and Action (TIGRA) coordinated boycotts against WU in order to compel the company to decrease fees. TIGRA, based in Oakland, California, also called upon WU and other global money transfer companies to reinvest more into local communities, at the tune of $1 dollar per every $100 in money transfer transaction revenues. A STORIED PAST Prior to the boycotts in 2007 and 2008, WU had a chequered history. Fourteen years after its founders set out to build the first U.S. telegraph giant, WU’s shares began trading on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in 1865. In 1884, WU became one of the original 11 companies included in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Over the years WU was featured in a Zane Grey novel and a movie depicting the company’s creation of an inaugural U.S. transcontinental telecommunications link. Innovation was WU’s hallmark: it had created the universal stock ticker, introduced the first consumer-to-consumer money transfer service, and launched the first U.S. commercial communications satellite service. However in 1992, WU went bankrupt, as telegraphs reached obsolescence, a victim of airmail and faxes, and the company was delisted from the NYSE. WU re-emerged in 1994 solely as a money transfer company. Owing to a surge in migration, money transfers were at that time growing at 20 percent per year. In 1998, Chicago 2|Page PRESENTED BY: lawyer Matthew Piers represented plaintiffs in a class-actions suit against WU and rival money transfer company MoneyGram, alleging that these firms had deceived customers with advertisements like, “Send $300 to Mexico for $15,” when, in fact, the companies derived even higher profits (about 80% more) from settling foreign exchange rates from money transfers into local currencies to their advantage. The case was settled without either company admitting any wrongdoing. After settling its share of the lawsuit for $375 million, a portion of which included the creation of a fund for immigrants’ organizations, WU set out to recast its image. An internal marketing memo asserted that that WU appeared “money-oriented” and “cold,” so the goal was modified to capture a “share of mind” and a “share of heart” in addition to a “share of wallet.” i WU spent more than $1 billion on marketing, selectively dropped money transfer fees, donated to immigrants’ rights groups and advocated a path to legalization for illegal immigrants. In sum, WU sought to portray itself as the migrants’ “trusted friend.”ii Matthew Piers, the lawyer who had brought the suit against WU later told a New York Times reporter: “Western Union has become a company that values and protects its customers. No one was more surprised at the change than me, as I was Western Union critic Numero Uno.”iii First Financial Management Corporation purchased WU in 1994, and a year later the combined entity merged with First Data Corporation in Colorado. In the ensuing ten years, WU grew its leading share of the consumer money transfer services market from 10 to over 17 percent, with an average transaction size of $350. By then, WU far exceeded other franchise businesses in terms of number of outlets worldwide – over 300,000 – compared with McDonald’s at 31,000 outlets, and processed nearly five times as many transactions as its closest 3|Page PRESENTED BY: rival, MoneyGram. WU offered services through a network of agents in more than 200 countries and territories, under the “Western Union” as well as its subsidiary brands, Orlandi Valuta (acquired in 1999 and based in Los Angeles, California) and Vigo Remittance Company (acquired in 2005 and based in Florida). WU was again listed on the NYSE on January 26, 2006. In fiscal year 2007, WU continued to derive the majority of its $4.9 billion revenues from fees that consumers paid when they sent money. WU’s primary segments included consumer-to-consumer (C2C: 83 percent of 2007 revenues) and consumer-to-business (C2B: 15 percent). Led by the same core group of executives that had managed it under First Data, in 2008 WU continued to carry $3.5 billion in residual debt on its balance sheet as a result of the spin-off from First Data. CEO Christina Gold, who had joined WU in September 2006, after serving as executive vice president of global development at Avon Products, was seen by many industry observers to have been primarily responsible for WU’s makeover. In 2007, Gold reflected upon her role to a reporter in Singapore: I look at running a company as stewardship for a period of time…I’m not the company — I try to keep that perspective because I think the brand stands for Western Union [and] I’m not the brand. I’m just a representative of the company and my organization and all of the people who work for it. As part of my stamp I hope to develop a positioning to be really recognized as a brand that stands for its consumers and it gives back to the community and it does things that are meaningful and make a difference. However, when I do leave, I want to leave behind a company that is more diverse in its revenue streams and has a human face.iv Jack Greenberg, former Chairman and CEO of McDonald’s and a member of First Data’s board of directors, had also moved over in 2006 to become chairman of WU. Together, Gold and 4|Page PRESENTED BY: Greenberg pursued growth of the WU brand through international expansion. WU’s revenues increased at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.4 percent from 2004 to 2007, driven by foreign exchange revenues that increased at a 19.7 percent CAGR, comprising 13 to 16 percent of total revenues during that period. See Exhibits 2-4 for WU’s 2005-2007 financial statements. CUSTOMERS AND MARKETS According to Morningstar, about 200 million people lived outside their country of origin in 2008.v The ongoing growth in the worldwide immigration population was concomitantly driving growth in the money transfer business. See Exhibit 5 for data on worldwide money transfers from 1990-2007. Most money transmitters had relationships with networks of agents that could collect and distribute cash across the globe — for a fee (see Exhibit 6 for estimated industry profits per transaction). Money transfers sent by immigrants back to their home countries typically were not discretionary, but covered the subsistence needs of their families. For instance, money transfers sent to El Salvador equaled more than 15% of that country’s GDP, according to Morningstar. COMPETITION WU competed with Global Payments Inc., Euromet Worldwide, and MoneyGram International. Exhibit 7 presents comparative financial information on these three direct competitors. However, indirect competitors in the money transfer industry included financial services businesses such as: credit unions, ATM operators, card associations, card-based 5|Page PRESENTED BY: payment providers, informal remittance systems, Web-based services, telephone payment systems, postal organizations, retailers, check cashing services, and currency exchange providers. Banks, mass retailers like Wal-Mart, and cell phones also emerged as alternative channels for immigrants seeking money transfers. By the year 2013, 100 millions of cell phone users were expected to transfer money via their mobile phones, according to Juniper Research.vi Many of these rivals were specialists in their industries or regions. Among the factors that gave certain rivals competitive advantages were local brand reputation, convenience, speed, varying payments, reliability, and price points. Pricing remained competitive in the money transfer business. Increasing price competition and regulatory burdens were driving out smaller rivals, leading to higher market shares for the remaining industry leaders. CORPORATE STRATEGY OR ECONOMIC JUSTICE? As increasing numbers of money-transfer companies and banks moved into the field, WU felt increasing pressure to lower prices and compete for customers. Some critics, like TIGRA, advocated that WU heighten its commitment to community development.vii Others, such as Efrain Jimenez, a community organizer in California who was spearheading a joint venture with WU for a Mexican community development project, were not so certain: “Yes, Western Union has a social responsibility, but they have the right as a company to make money too. They aren’t a charity.”viii WU officials proclaimed that about $40 million in aid had been donated by the company’s foundation to groups in 70 countries since 2000. These officials also maintained that the company had been aggressive in its philanthropy, while acknowledging that theirs was a corporate strategy also aimed at defending its business against the emergence of banks and other 6|Page PRESENTED BY: rivals in wire transfers.ix In late spring 2008, WU publicly committed $50 million in donations to charitable organizations for the next five years.x In July 2008, the Arizona Court of Appeals overturned a trial court’s ruling in WU’s favor regarding the authority of the Arizona Attorney General to seize money transfers originating in states other than Arizona and intended for payment in Mexico. WU subsequently asked the Arizona Supreme Court to reconsider this matter. Meanwhile, Arizona’s Attorney General did not attempt to resume the type of seizures at issue in this litigation, and WU did not experience any immediate measurable impact to its Americas money transfer business as a result of this decision. The legal situation in Arizona remained unresolved as of November 2008. Future Prospects By late autumn of 2008, several forces had converged that could severely dampen WU’s future prospects. A weak global employment market had prompted many money transfer customers — immigrants — to remain in their home countries. The global financial services industry was in free-fall after the failures of Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, and AIG, among other large financial services providers. Steep declines in the U.S. construction industry as well as the ongoing immigration debate in various state legislatures and the U.S. Congress slowed money transfer growth in the U.S.-Mexico corridor, WU’s most profitable segment. Standard & Poor’s analysts at that time nevertheless remained bullish on WU’s prospects, targeting compound annual revenue growth at 8 percent out to 2012.xi A reason for analysts’ optimism was that WU had generated $800 million of free cash flow during the first 7|Page PRESENTED BY: nine months of 2008, that is, for the first three fiscal quarters ending September 30, 2008. Exhibit 8 presents operating segment data for third quarter 2008 and for the first nine months of fiscal 2008. WU repurchased 17 million shares (at a total cost of $385 million) in the second quarter; and another 20 million shares (at a total cost of $523 million) in the third quarter of fiscal 2008. CEO Gold had recently stated WU’s intention to devote free cash to stock repurchases and acquisitions of rival money transfer firms.xii Yet at the November 10, 2008 meeting with executives Ochoa and Duany, among the competing options on the table were: development of innovative financial services products that could be sold through the growing network of 335,000 WU agents worldwide, or perhaps even the creation of a micro-lending or small business development grant program for customers in developing nations. Endnotes i DeParle, J. (November 22, 2007). "A Western Union Empire Moves Migrant Cash Home," The New York Times, A1. ii Ibid. iii Ibid. iv Choudhury, A.R. (November 24, 2007). “Christina Gold, the high-flying head of remittance firm Western Union, has her feet firmly planted on the ground,” Business Times Singapore. v “Western Union,” (October 13, 2008). Morningstar Reports. vi Juniper Research (October 7, 2008). “100 Million Mobile Users to Make International Money Transfers by 2013.” Wireless News. vii Thompson, G. (2007, May 11). “Immigrants push Western Union to Share the Wealth,” The Nation, http://www.thenation.com/doc/2070528/thompson/print. viii Avila, O. and Olivo, A. (October 21, 2007). “Western Union Boycott Divides,” Chicago Tribune. ix Ibid. x See http://www.transnationalaction.org/research/index.html#more, accessed December 12, 2008. xi “Western Union,” ((November 8, 2008). Standard & Poor’s. xii See July 22, 2008 Bloomberg TV interview with CEO Christina Gold at: http://www.clipsyndicate.com/publish/video/649933/spotlight_western_union 8|Page PRESENTED BY: Exhibit 1: Western Union Shareholder Resolution, 2008 The federal law known as the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) obligates federally insured banks and depository institutions to help meet the needs of communities in which they operate. No such law exists for money transfer agencies like Western Union. In March 2007, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke stated, "the CRA reaffirmed the long-standing principle that financial institutions must serve the convenience and needs...of the communities in which they are chartered.”(1) Western Union serves many of the financial needs of immigrant populations, as a bank might, with a major presence in poor and racially diverse neighborhoods.(2) Western Union's customers are mostly urban and poor. The typical user of its remittance services is a low-wage immigrant worker who lives in urban America, makes $15,600 annually and sends home $293 a month, almost 30% of his or her net monthly income.(3) These remitters spend up to $300 a year on costly transaction fees and disadvantageous exchange rates, which equals one week's salary for the remitter or at least sixty days' salary for their kin in cities such as San Salvador, Mexico City, and Manila.(4) Remittances contribute about 80% to a recipient household's total income. Almost half of Philippine households who receive remittances depend solely on this source of income. The highest monthly allocations for expenses from remittances are for food, rent, and education.(5) We believe onerous charges in the multi-billion dollar money transfer industry place an undue economic burden on low-income immigrant families in the United States and in their communities of origin while creating an increased reputational risk for our Company. Western Union has faced numerous lawsuits based on predatory fees and unfair exchange rates. These suits have resulted in millions of shareholder dollars being spent on settlements. These practices, along with our Company's relatively low degree of community reinvestment, increase the risk our Company faces in the competitive consumer market. BE IT RESOLVED THAT: the Company develop and implement a written policy for community reinvestment. SUPPORTING STATEMENT: In our view, community investment goes beyond charitable donations and corporate volunteering. We believe a policy and strategy to build social capital in communities is essential. Such a policy is best created by engaging community organizers to identify community needs to develop long-term programs that reflect those needs. (1) The Community Reinvestment Act: Its Evolution and New Challenges, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke, 3/30/07. (2) Analysis of Alternative Financial Service Providers, Urban Institute, 2004. (3) Distributing Prepaid Cards through Worker Centers: A Gateway to Asset Building for Low-Income Households, The Center for Financial Services Innovation, October 2006. (4) Transnational Institute for Grassroots Research and Action Research, April, 2007. (5) Enhancing the Efficiency of Overseas Workers Remittance, Asian Development Bank, July 2004. Source: Responsible Wealth, Boston, MA, http://www.faireconomy.org/news/western_union_shareholder_resolution_2008, accessed June 14, 2009. 9|Page PRESENTED BY: Exhibit 2: WESTERN UNION CO — Income Statements, 2005-2007 ($ Millions except per share amounts) Transaction Fees Foreign Exchange Revenue Commission & Other Revenues Total Revenues Cost of Services Selling, General & Administrative Expense Total Expenses Operating Income Interest Income Interest Expense Other Income (Expenses), net Income before Income Taxes - Domestic Income before Income Taxes - Foreign Income before Taxes Provision for Income Taxes Net Income 12/31/05 $3,354.8 531.0 102.1 $3,987.9 2,118.9 599.8 2,718.7 1,269.2 0.0 0.0 74.9 801.9 542.2 1,344.1 416.7 $927.4 Weighted average shares outstanding-basic (millions of shares) Weighted average shares outstanding-diluted (millions of shares) Year end shares outstanding (millions of shares) Earnings per share - basic Earnings per share - diluted Total number of employees Number of stockholders 12/31/06 $3,696.6 653.9 119.7 $4,470.2 2,430.5 728.3 3,158.8 1,311.4 40.1 (53.4) 37.0 707.1 628.0 1,335.1 421.1 $914.0 12/31/07 $3,989.8 771.3 139.1 $4,900.2 2,808.4 769.8 3,578.2 1,322.0 79.4 (189.0) 10.0 529.3 693.1 1,222.4 365.1 $857.3 764.5 768.6 771.1 $1.20 $1.19 5,900 4,513 760.2 772.9 749.8 $1.13 $1.11 6,100 4,542 Sources: Mergent Online, accessed November 14, 2008, and company SEC filings. Exhibit 3: WESTERN UNION CO — Balance Sheets, 2005-2007 ($ Millions) ASSETS Cash & Cash Equivalents Accounts Receivable Other Current Assets Total Current Assets Property, Plant & Equipment, net Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets, net TOTAL ASSETS 12/31/05 $510.2 2,215.4 2,725.6 82.4 1,798.4 $4,606.4 LIABILITIES AND SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY Accounts Payable & Accrued Liabilities $238.6 Other Current Liabilities 5,054.8 Total Current Liabilities 5,293.4 Long Term Debt Borrowings Stockholders’ Equity (687.0) $4,606.4 TOTAL LIABILITIES AND STOCKHOLDERS’ EQUITY Sources: Mergent Online, accessed November 14, 2008, and company SEC filings. 12/31/06 12/31/07 $1,421.7 24.3 1,763.3 3,209.3 176.1 1,935.7 $5,321.1 $1,793.1 22.5 1,794.7 3,610.3 200.3 1,973.6 $5,784.2 $554.8 2,085.2 2,640.0 2,995.9 3,323.5 (314.8) $5,321.1 $350.1 2,883.6 3,233.7 2,499.8 3,338.0 50.7 $5,784.2 10 | P a g e PRESENTED BY: Exhibit 4: WESTERN UNION CO — Statements of Cash Flow, 2005-2007 ($ Millions) Net Income Depreciation & Amortization Other Assets, net Other Liabilities, net Net Cash Flows from Operating Activities Capitalization of Contract Costs Capitalization of Purchased & Developed Software Capitalization of Software Development Costs Purchases of Property & Equipment Notes Receivable Issued to Agents Repayments of Notes Receivable Issued to Agents Acquisition of Businesses, Net of Cash Acquired, & Contingent Purchase Consideration Paid Cash Received (Paid) on Maturity of Foreign Currency Forwards Purchase of Equity Method Investments Net Cash Flows from Investing Activities Net Proceeds from Commercial Paper Net Proceeds from/(Repayments of) Net Borrowings under Credit Facilities Proceeds from Exercise of Options Cash Dividends to Public Stockholders Common Stock Repurchased Advances From/(To) Affiliates of First Data Capital Contributed by First Data in Connection with Acquisitions Notes Payable Issued to First Data Repayments of Notes Payable to First Data Additions to Notes Receivable from First Data Proceeds from Repayments of Notes Receivable from First Data Dividends to First Data Proceeds from Issuance of Debt Principal Payments on Borrowings Purchase of Treasury Shares Net Cash Flows from Financing Activities 12/31/05 $927.4 79.5 42.4 (46.5) $1,002.8 12/31/06 $914.0 103.5 (4.3) 95.7 $1,108.9 12/31/07 $857.3 123.9 85.2 37.1 $1,103.5 (22.5) (124.1) (80.9) (27.7) (7.7) (34.8) (8.4) (14.4) (63.8) (140.0) 20.0 (83.5) (6.1) 32.0 (349.1) (0.5) (5.4) ($428.4) (66.5) 4.1 0.0 ($384.7) (35.8) ($202.0) 0.0 324.6 13.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 (153.2) 369.2 400.1 (246.5) (504.7) 18.4 (417.2) 3.0 80.8 (7.7) 0.0 160.2 (3.0) 216.1 (30.0) (726.8) 0.0 ($533.9) Net Change in Cash & Cash Equivalents $40.5 Cash & Cash Equivalents at Beginning of Year 469.7 Cash & Cash Equivalents at End of Year $510.2 Sources: Mergent Online, accessed November 14, 2008, and company SEC filings. (154.5) (7.5) 776.2 (2,953.9) 4,386.0 (2,400.0) (19.9) $187.3 0.0 ($530.1) $911.5 510.2 $1,421.7 $371.4 1,421.7 $1,793.1 11 | P a g e PRESENTED BY: Exhibit 5: Global Remittances (total $ billions sent home by migrants around the world), 1990-2007 $350 $300 $300 $269 $232 $250 $200 $132 $150 $100 $ billions $102 $67 $50 $0 1990 1995 2000 2005 2006 2007 est. Sources: DeParle, J. (2007, November 22) "A Western Union Empire Moves Migrant Cash Home," The New York Times, A1; Transnational Institute for Grassroots Research and Action (TIGRA) http://www.boycottwesternunion.net/En/about.htm; Khakimov, S. (2008, February 29), "Can One Build a House Without A Base?" Results from The UN Forum on Remittances, http://www.scribd.com/doc/12911117/Resultsfrom-the-UN-International-Forum-on-Remittances-20071. Exhibit 6: Estimated Industry Profit per Transaction ($), 2007 $20.00 $18.00 $16.00 $14.00 $12.00 $10.00 $8.00 $6.00 $4.00 $2.00 $0.00 $16.01 $15.71 $14.28 Average profit per transaction Average cost per transaction $2.94 $2.94 $2.94 Western Union Dolex MoneyGram Sources: DeParle, J. (2007, November 22) "A Western Union Empire Moves Migrant Cash Home," The New York Times, A1; Transnational Institute for Grassroots Research and Action (TIGRA) http://www.boycottwesternunion.net/En/about.htm. 12 | P a g e PRESENTED BY: Exhibit 7: Comparative Financial Data — Payment Processing and Services (as of November 1, 2008) 52 Week Price Range 11/1/07 – 11/1/08 Company Western Union Global Payments Euronet Worldwide MoneyGram International Stock Symbol WU EEFT GPN MGI Market Cap. $ million $ 11,084.0 $ 3,294.0 $ 487.0 $ 81.0 TTM Sales $ million $5,179.0 $1,369.0 $1,026.0 $ 470.0 TTM Operating Income $ million $1,340.0 278.0 81.0 nil TTM Net Income $ million $ 898.0 177.0 37.0 (1,480.0) Beta 1.00 0.74 1.59 1.94 Dividend Yield % 0.30% 0.02% nil 20.83% High $28.62 $49.87 $33.25 $19.21 Low $12.28 $35.05 $7.79 $0.80 P/E Ratio (x) 10.97 16.81 16.69 NMF TTM = Trailing Twelve Months NMF = Not Meaningful Figure Sources: Standard & Poor’s Stock Report: Western Union Co, November 8, 2008; Google Finance, accessed November 14, 2008. 13 | P a g e PRESENTED BY: Exhibit 8: Operating Segment Data for Western Union, First Nine Months of FY 2008 v. FY 2007 Operating Segment Consumer-to-Consumer Revenue EMEASA (A) APAC (B) AMERICAS (C) Total Consumer-to-Consumer (D) Consumer-to-Business Other TOTAL Three Months Ended 9/30/08 45% 33% 7% 85% 13% 2% 100% Three Months Ended 9/30/07 41% 36% 7% 84% 14% 2% 100% Three Months Revenue Growth % Three Months Transaction Growth % 20% 0% 23% 27% 1% 30% Nine Months Ended 9/30/08 44% 34% 7% 85% 14% 1% 100% Nine Months Ended 9/30/07 40% 37% 6% 83% 15% 2% 100% Nine Months Revenue Growth % Nine Months Transaction Growth % 22% 0% 28% 26% 3% 26% (A) EMEASA = Europe, Middle East, Africa and South Asia. (B) APAC = Asia/Pacific (C) AMERICAS = North America, Latin America, the Caribbean, and South America. (D) The geographic split was determined based upon the region where the money transfer was initiated and the region where the money transfer was paid, with each transaction and the related revenue split 50% between the two regions. For those money transfer transactions that were initiated and paid in the same region, 100% of the revenue and transactions were attributed to that region. Source: Western Union Form 10-Q, Quarterly Report, SEC filing November 3, 2008, 34-37. 14 | P a g e