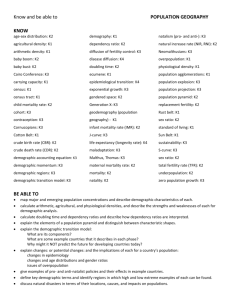

the shape of things to come

advertisement