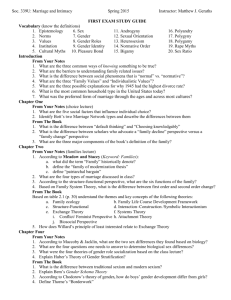

RAM - OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center

advertisement