memorandum - Temple Fox MIS

advertisement

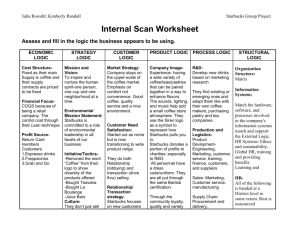

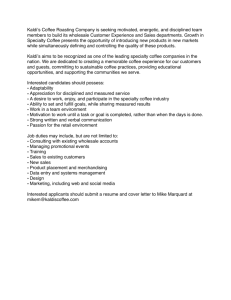

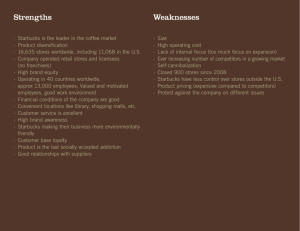

MEMORANDUM TO: FROM: DATE: RE: V.G. Siddhartha, Founder and Chairman, ABC Trading Company Christina Barcello, Tuesday/Thursday 9:30 April 23, 2015 Strategic Planning for Café Coffee Day EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Café Coffee Day successfully developed a robust café culture in India utilizing a focused differentiation strategy. Starbucks has adopted a very similar strategy to CCD’s for their expansion into the Indian market. CCD’s key strategic objective is maintaining their title as India’s leading coffee chain, forfeiting very little of their sixty percent market share in the Indian retail coffee industry to Starbucks as the global brand continues to expand throughout the country. Attracting and retaining talent has been an issue for CCD, which directly effects the quality of their customer service. Additionally, the real estate market has hardened, making it increasingly difficult to acquire desirable properties for a reasonable price. This report will conduct a situation analysis of the internal and external environment, present key findings and offer recommendations as to how CCD can maintain their position in the Indian retail coffee market. External Analysis of the Indian Market: GDPEST (Exhibit 1) Global: Chain coffee retailers are increasingly expanding their stores on a global scale. Companies based in Italy, Australia, the U.S. and the U.K. have all entered the Indian market in the past ten years. The food service volume of fresh coffee grew more than forty percent in India between 2005 and 2011 (HBR, 2013). Demographic: A 2012 chart depicting age distribution in India shows the country is made up of primarily younger residents. There are more Indian men and women between the ages of 15 and 30 living in the country than any more senior age bracket. Indians tend to be price conscious consumers. The average citizen isn’t willing to pay a premium for coffee at a café they could buy less expensively elsewhere. Most coffee retailers in India target middle and upper middle class. Political/Legal: As a result of the coffee market being deregulated in 1993, Indian coffee farmers are no longer obligated to sell their produce to the Coffee Board as they were in the 1980s (HBR, 2013). With the freedom to sell their crops to anyone they wish, there is greater opportunity for farmers to earn substantial profits on coffee than previous to this legislative change. Sociocultural: Job opportunities in India are less limited than they were seven to ten years ago. Many coffee retailers have begun to offer higher wages to their workers, making it difficult for companies with less attractive compensation packages to attract and retain employees. Economic: The growth of the Indian retail industry has made it increasingly difficult to find good properties for a fair price. Technological: Heightened accessibility of the internet has eliminated the appeal of patronizing a café in order to use their network. Free Wi-Fi is now a commonplace amenity in many specialty coffee shops. Porter’s 5 Forces (Exhibit 2) CCD operates in the retail coffee industry. The threat of new entrants in the Indian retail coffee industry is high because the barriers to entry are low. In the past ten years, five major chains (Costa Coffee, Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf, Gloria Jean’s, Dunkin Donuts, and Starbucks) have entered the Indian market. In 2011, ninety-five percent of the 2300 specialist coffee shops in India belonged to chains and both new and established chains had plans in place to expand rapidly (HBR, 2013). One barrier to entry resulting from this rapid growth is the increased difficulty of finding property for a café that is both desirable and affordable. Potential entrants to the retail coffee market in India need a large amount of startup capital just to purchase a storefront. Additionally, a potential entrant should consider the costs of receiving assistance from local companies to familiarize themselves with the Indian market. Suppliers have a high degree of control in the Indian coffee industry. Some retailers in the Indian coffee industry, such as Tata and CCD produce their own coffees, enabling them to “save the best product for themselves” rather than buying from the market. The result is less buying power for the retailers that do not grow their own product. The primary substitute to purchasing coffee beverages in a café setting is at home consumption. Price conscious consumers are likely to shop for coffee in a super or hypermarket, where they will pay much less for the same product. In response to this consumer behavior, many traditionally café-format retailers such as CCD, Dunkin Donuts, and Starbucks have developed their own brand of these products, in order to capture a portion of the twenty percent of coffee sales taking place in these grocery and department stores. Internal Analysis of the Indian Coffee Industry: VRIS (Exhibit 3) CCD’s greatest capability is having control over every aspect of their processes and operations. The company is the only player in the industry that is fully vertically integrated; owning their plantations, roasting and blending facilities, and cafés. As a result of their involvement in every step of the process, consumers view CCD as coffee experts. This business model creates a sustainable competitive advantage for CCD because it is valuable, rare, costly to imitate and non-substitutable. CCD has no plans to franchise in order to ensure quality control of their product. Sixty percent of CCD customers visit a café twice a week or more. CCD classifies these customers as “regulars”, and makes an effort to retain their loyalty throughout the customers’ lifetime. The chain does not anticipate Starbucks forming similar relationships with their customers as their store is targeted more towards tourists and status symbol seeking individuals. In a country where dating at a young age is not encouraged, CCD provides an acceptable and safe outlet for youth to gather. The retailer was recently named one of India’s most trusted brands by Economic Times, a valuable title to carry with new companies entering the industry frequently. An uncertain consumer may be more likely to patronize a local chain with a trustworthy reputation rather than a foreign brand they don’t know much about. Finally, although it does not advertise itself as a cost leader, there is a big gap in pricing between CCD and most of its competitors offering similar food and beverage products. CCD’s goal is to source at prices at least twenty percent lower than competitors (HBR, 2013). The company has resisted the temptation to raise menu prices because they believe affordable pricing will lead to more customers. Business Strategy (Exhibit 4) CCD exercises a focused differentiation strategy. The company has three unique store concepts each targeted at a different demographic. CCD’s cafés represent ninetyseven percent of the company’s portfolio, attracting India’s large younger population with espresso beverages, snacks, jukeboxes, and merchandise. For customers over 30, CCD’s lounges and squares are equipped with full kitchens and chefs, aiming to keep the interest of their past generations of target customers. Key Findings: Starbucks has a very similar business strategy to CCD, in terms of where their stores are located, placing emphasis on building customer loyalty and not advertising, even using a vertically integrated business model through their joint venture with Tata. For CCD, primary issues include attracting and retaining talent, sub-par customer service levels, and difficulty in finding good real estate for an affordable price. Additionally, CCD emphasizes the importance of maintaining relationships with regular customers who “grew up with” their brand, and keeping consumers engaged requires adopting all the latest food trends. Recommendations: CCD needs more than a “slight course correction” to handle Starbucks entering the Indian market. Yes, CCD needs to constantly improve the quality of the menu and infrastructure of their cafés in order to stay “on trend” for the young target demographic. More importantly, CCD should try to offer consumers something unique rather than just being a “better Starbucks”. CCD’s original strategy was to “seed the café culture rapidly in different cities, and accelerate the establishment of the brand” (HBV, 2013). The company should stand by that initiative and continue to expand their portfolio of cafés rather than intensively focusing on re-branding and remodeling. Another recommendation is for CCD to improve the level of service provided through both better training and compensation for their employees to avoid losing valuable team members to Starbucks. Implementation: Starbucks is producing their own coffee and furniture, customizing menus to suit regional tastes, setting up training centers for employees, and opening stores in high traffic areas of India. In preparation for Starbucks’ expansion within the Indian market, CCD executives have begun making improvements to their brand such as remodeling cafés and lounges, improving menu offerings, and increasing marketing efforts in order to remain the dominant coffee café in India. Increasing marketing efforts during Starbuck’s expansion into the Indian market is a good use of CCD’s resources because it gives them an opportunity to remind consumers of what is unique about their brand. However, improving service levels is most vital in maintaining the top spot in the Indian retail coffee industry. CCD should consider increasing benefits offerings in order to attract the more motivated employees. The current business model that earned CCD great success should not be drastically altered. CCD should not abandon their commitment to being reasonably priced in the quest to stay on trend by revamping the menu. Furthermore, rather than battling with Starbucks for the remaining desirable real estate in India’s larger cities, CCD should expand in smaller Indian cities now before their Starbucks has a complete grasp on how to successfully operate in those locations. CCD can take advantage of cheaper properties in smaller cities and keep the rent to revenue ratio below twenty percent. Works Cited Bijlani, Tanya, Yoffie B. David. “Coffee Wars in India: Café Coffee Day Takes On the Global Brands.” Harvard Business School, 23 April. 2015. Web. 8 August 2013. <https://cb.hbsp.harvard.edu/cbmp/content/31945129>

![저기요[jeo-gi-yo] - WordPress.com](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005572742_1-676dcc06fe6d6aaa8f3ba5da35df9fe7-300x300.png)