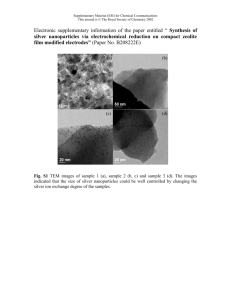

Silver Nanostructures: Chemical Synthesis of colloids and

advertisement