The Critical Psychological States: An Underrepresented Component

advertisement

Journal of Management

199.5,Vol. 21, No. 2,279-303

The Critical PsychologicalStates:

An Underrepresented Component in

Job Characteristics bode/ Research

Robert W. Rem

2% Universityof Memphis

Robert J. Vandenberg

university of Georgia

The mediating role of the critical psychological states (CPS) in

the job characteristics model was examined in two studies. Using

Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach for examining mediation

hypotheses, results from Study 1: (1) supported the hypothesized

linkages between the core job dimensions and the CPS, and between

the CPS and attitudinal outcomes; (2) provided no support for the

hypothesis that all three CPS must be experienced to m~Kirniz~

internal work motivation; (3) supported the present authors’

hypothesis that the CPS would explain signt&mt amounts of

outcome variance beyond the core job dimensions; and (4) supported

the present authors *hypothesis that the CPS are partial rather than

complete mediator var~~b~es~Using causal modeling analyst and

another sample, results from Study 2 provided the strongest support

for a job characteristics modeI that allowed the core job dimensions

to have direct and indirect effects on personal and work outcomes,

further supporting the Study 1 finding that the CPS were partial

mediator variables. The general discussion centered on the

implications the present findings have for future job characteristics

model research.

Hackman and Oldham’s (1976) job characteristics model has stimulated over

200 published empirical studies and at least three comprehensive reviews (e.g.,

Fried & Ferris, 1987; Loher, Noe, Moeller & Fitzgerald, 1985; Roberts & Glick,

1981). In their review, Fried and Ferris (1987) found that only eight studies

included the critical psychologic~ states (CPS), and only three of those eight

studies examined the CPS mediation hypothesis (Arnold & House, 1980;

Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Wall, Clegg & Jackson, 1978).

That the CPS mediation hypothesis rarely has been examined is not a trivial

issue. First, Hackman and Lawler (1971), and Hackman and Oldham (1975;

Direct all correspondent

to: Robert W. Renn, The University of Memphis,

and Economics, Department of Maaa~ment,

Memphis, TN 38152.

Copyright

@ 1995 by JAI Press Inc. 031494063

Fogelman

College of Business

280

RENN AND VANDENBERG

1976) presented the CPS as the primary motivational component of the job

characteristics model. Since few studies have included the CPS, one could

question whether the motivational underpinnings of this theory have been

adequately examined or represented in job characteristics model evaluations

(Gardner & Cummings, 1988; Kanfer, 1991). Second, excluding the mediating

role of the CPS could be overlooked if there was enough evidence supporting

their exclusion. Excluding the CPS from tests of the theory, thus, would have

represented the normal practice of modifying a theory as warranted by the

accumulated evidence (Bacharach, 1989). For instance, sufficient empirical

evidence has accumulated to support evaluating the relations among the job

characte~stics model’s components without the growth need strength moderator

(Graen, Scandura & Graen, 1986; Johns, Xie & Fang, 1992; Tiegs, Tetrick &

Fried, 1992). By contrast, virtually no empirical evidence has accumulated

supporting the practice of excluding the CPS from tests of the theory. In fact,

Hogan and Mat-tell suggested that the CPS have been excluded from past studies

not because the empirical evidence supported this trend but because of the

analytical difficulties associated with testing the mediation hypothesis (1987, p.

244). Thus, the practice of excluding the mediating role of the CPS appears to

have occurred without theoretical or empirical justification.

The purpose of the present research was to examine the soundness of

excluding the mediating role of the CPS from the job characteristics model.

This was accomplished through two studies, both of which addressed the

following underlying question: Do the CPS make a contribution to our

understanding of indi~duals’ reactions to their jobs, or are the CPS an

unnecessary component of the job characteristics model whose exclusion would

make the theory more parsimonious? In addressing the latter question, the

present research was critical in nature. Specifically, in both studies the

hypothesis that the CPS are important components of the job characteristics

model was tested against the alternative hypothesis that they may not be

necessary, and that their removal may result in a more parsimonious

explanation of job design processes (Harris & Schaubroeck, 1990; James,

Mulaik & Brett, 1982). The present research was also critical in that, assuming

the CPS possess a mediating role, the nature of that role (i.e., whether the CPS

are complete or partial mediators) was examined in a series of hypotheses that

contrasted the theoretical statements of that role with the accumulated empirical

evidence. It is important to note that the purpose of the present research was

not to examine every nuance of the job characteristics model, but rather, only

the role the CPS have in the model. In the following sections, we provide a

basis for the present research question by briefly reviewing the role of the CPS

in the job characteristics model and the findings from studies that included the

CPS.

The Role of the CPS in the Job Characteristics Model

Hackman and colleagues (Hackman & Lawier; 1971; Hackman & Oldham,

1976; 1980) used the CPS to provide a theoretical link between perceived job

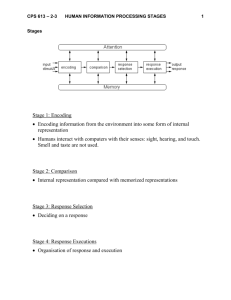

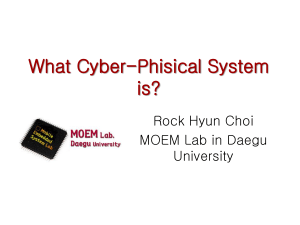

characteristics and internal work motivation. As can be seen in Figure 1, internal

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21. NO. 2. 1995

ldentl

Feedback

IAutonomy

Task Slgnlf

l&k

lcance

ty

Sk111Variety

Core Job

Dimensions

F

Figure 1.

I

J

The Job Characteristics

Know I CYly]c of the

Flc tual

Resul ts of

Work Flc tlvl ties

Exper 1enc ed

Responslblll

ty

for Outcomes

of the Work

Exper i one ed

Meaninyfulness

of

the Work

Crltlcal

Psychologlcal

States

Model

Internal

and Turnover

1.0~ Ilbsentceism

HI gh Sat I sfac t 1on

WI th the Work

Quai 1 ty

Work Performance

tllgh

1JorkMotlvatlon

llicjh

Personal and

Work Outcomes

F

r

iA

2

;;1

WY

6

0

g

2

2

g

$

7

E

282

RENN AND VANDENBERG

work motivation is hypothesized to result from work that prompts three CPS,

experienced

meaningfulness,

experienced

responsibility,

and knowledge of

results. Experienced meaningfulness refers to the extent to which an individual

believes his or her job is important vis a vis the individual’s own value system.

Experienced responsibility represents the degree of personal accountability

an

individual has for his or her work outcomes. And knowledge of results refers

to the extent to which an individual knows how well he or she is performing

on the job.

Hackman and colleagues hypothesize that the three CPS are prompted

by work consisting of five core job dimensions. Skill variety (the breadth of

skills used while performing work), task identity (the opportunity to complete

an entire piece of work), and task significance (the impact the work has on

others) are hypothesized

to prompt experienced meaningfulness.

Autonomy

(the depth of discretion allowed while performing work) is hypothesized

to

prompt experienced responsibility. And feedback (the amount of information

provided about work performance)

is hypothesized

to cause knowledge of

results. In brief, greater amounts of these five core job dimensions are postulated

to lead to stronger experiences of the three CPS which, in turn, lead to more

positive responses to work as evidenced by changes in both attitudinal (e.g.,

increased internal work motivation,

increased job satisfaction,

decreased

turnover intentions, etc.) and behavioral (increased performance,

decreased

turnover, etc.) outcomes.

Although never explicitly stated by Hackman and colleagues, Figure 1

indicates that the CPS are complete mediators of the core job dimensions-outcomes

relations. That is, the effects of the core job dimensions on personal and work

outcomes are shown to be fully transmitted by the CPS (Baron & Kenny, 1986;

James, 1980; James & Brett, 1984). Also, as mentioned, Hackman and Oldham

state that “the five core job dimensions are seen as prompting three psychological

states, which, in turn, lead [italics added] to a number of beneficial personal and

work outcomes” (1976, p. 255). Hackman and Oldham emphasize the impact the

CPS have on personal and work outcomes by labeling them the job characteristics

model’s “causal core” (1976, p. 255). Finally, Hackman et al. hypothesize that ail

three CPS must be experienced to maximize internal work motivation.

Examinations of the Mediation Hypothesis

Few studies have examined the hypothesized mediating role of the CPS

in the model (cf. Arnold & House, 1980; Champoux,

1991; Fox & Feldman,

1988; Fried & Ferris, 1987; Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Hogan & Martell, 1987;

Johns et al., 1992; Tiegs et al., 1992; Wall et al., 1978). Instead, studies that

included the CPS typically examined the linkages between the core job

dimensions and the CPS (e.g., Does skill variety correlate with experienced

meaningfulness?),

and between the CPS and attitudinal

and behavioral

outcomes

(e.g., Do the CPS correlate

with internal work motivation,

performance,

and turnover?). Although correlation studies cannot be viewed

as tests of the mediation hypothesis (Fried & Ferris, 1987), they do provide

some insight into the hypothesized linkages among the model’s components.

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

CRITICAL

PSYCHOLOGICAL

STATES

283

Regarding the core job dimensions-CPS linkages, task identity has not

always related well to experienced meaningfulne-ss. Instead, task identity has:

(1) operated just the opposite of what was originally hypothesized (Miner, 1980);

(2) not related to any CPS (Fox & Feldman, 1988; Hackman & Oldham, 1976);

or (3) related better to experienced responsibility or knowledge of results than

to experienced meaningfulness (Arnold & House, 1980; Fried & Ferris, 1987;

Johns et al., 1992). Autonomy has been shown to relate equally well to all three

CPS (Arnold & House, 1980; Fried & Ferris, 1987). Feedback, in general, has

related well to knowledge of results, although Fried and Ferris’ (1987) meta

analysis showed feedback related equally well to all three CPS. Skill variety

and task significance have related well to experienced meaningfulness.

Regarding the CPS-outcomes linkages, the CPS have related well to

internal work motivation, growth satisfaction, and general satisfaction (Fried

& Ferris, 1987; Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Johns et al., 1992). They have not,

however, consistently related well to performance or absenteeism (cf. Berlinger,

Glick & Rodgers, 1988; Fried & Ferris, 1987; Griffin, Welsh & Moorhead, 1981:

Griffin, 1991; Hackman & Oldham, 1976). The Fried and Ferris (1987) metaanalysis found that experienced meaningfulness had stronger associations with

attitudinal outcomes than did responsibility or knowledge of results, but a more

recent study by Johns et al. (1992) showed that the three CPS related equally

well to attitudinal outcomes.

A few studies have examined whether the CPS mediated the relations

between the core job dimensions and outcomes and/or the requirement that

all three CPS must be experienced. With regard to their role as mediators,

Hackman and Oldham (1976) demonstrated that the CPS completely mediated

the effects of fewer than half of the hypothesized linkages between the core job

dimensions and personal and work outcomes. That is, after controlling for the

CPS, many of the core job dimensions had significant associations with the

outcome variables. Hackman and Oldham’s findings, thus, suggested that the

CPS were partial mediators of most of the core job dimensions-outcomes

relations. Johns et al., (1992) showed that meaningfulness and responsibility

did not completely mediate the relations between skill variety, autonomy, and

a set of personal and work outcomes. With regard to the requirement of

experiencing all three CPS, reviews and studies have not supported the

hypothesis that all three CPS must be experienced to maximize improvements

in personal and work outcomes (Arnold & House, 1980; Fried & Ferris, 1987;

Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Johns et al., 1992).

To summarize, these findings appear to suggest that: (1) some of the core

job dimensions may not relate as expected to their theoretically specified CPS;

(2) the CPS may relate more strongly to attitudinal outcomes than to behavioral

outcomes; (c) the CPS may be partial mediator variables; and (d) all three CPS

may not be necessary to optimize improvements in personal and work outcomes.

Recall, however, that the majority of the above studies did not examine the

mediation hypothesis. Consequently, the collective findings derived from these

studies must be viewed as only suggestive of a lack of support and not conclusive

evidence against the hypothesized mediating role of the CPS. It seems

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

important, therefore, for additional research to focus on answering the question

of whether the CPS should be included in the job characteristics model and,

if so, in what form their role should be modeled.

The Present Research

Two studies were conducted to address the latter issue. Study 1 was

primarily a test of the original mediation hypothesis using Baron and Kenny’s

(1986) mediation testing approach. The first question addressed in Study 1 was

the main one underlying the stated purpose of the present research: Do the CPS

mediate the relationship between the core job dimensions and personal and

work outcomes, or are they an unnecessary component of the job characteristics

model per the impression given by the bulk of studies excluding them from

their tests? As noted earlier, we found no evidence to suggest that they should

be excluded. Thus, we predicted that:

Hypothesis I: The CPS will mediate the relations between the core

job dimensions and outcomes.

Although never explicitly stated by Hackman and colleagues (Hackman

& Lawler, 1971; Hackman & Oldham, 1976; 1980), an examination of both

past and contemporary portrayals of the job characteristics model (i.e., Figure

1; Hogan & Martell, $987) gives the impression that the CPS are complete

mediators of the core job dimens~ons~ut~omes relations. That is, the job

characteristics model suggests that the core job dimensions’ total effects on

outcomes are transmitted through the CPS (James & Brett, 1984). As noted,

however, there is empirical evidence indicating that the core job dimensions’

total effects may not be fully transmitted through the CPS (e.g., Hackman &

Oldham, 1976; Johns et al., 1992). First, one cannot ignore that fact that two

meta-analyses show that core job dimensions have significant direct effects on

outcomes (Fried & Ferris, 1987; Loher et al., 1985). Second, in tests including

the CPS, there exists support for the core job dimensions’ direct effects and

indirect effects through the CPS on outcomes. This empirical evidence,

therefore, suggests that the CPS may be partial rather than complete mediators.

Study I was designed to test this aspect of the CPS’ mediating role more

explicitly than has previous research. Based on the evidence bearing on the

question of complete or partial mediation, we predicted that:

Hypothesis 2: The CPS will be partial mediators in that the core

job dimensions will have direct effects on outcomes, and indirect

effects through the CPS.

Unlike the above, Hackman and Oldham do state explicitly that all three

CPS must be experienced to maximize the explanation of internal work

motivation (1976, p. 256). However, like the above, there is empirical evidence

suggesting that this aspect of the mediation hypothesis may not hold.

Specifically, the Hackman and UIdham (1976) and Arnold and House (1980)

JOURNAL

OF MA~A~~M~~,

VOL. 21, NO. 2.199.5

CRITICAL

PSYCHOLOGICAL

285

STATES

studies show that all three CPS are not necessary to maximize the explanation

of outcome variance. Thus, we predicted that:

Hypothesis 3: All three CFS will not be necessary to maximize the

explanation of outcome variance; however, the CPS will account for

significant amounts of outcome variance beyond the core job

dimensions.

Study 2 represented a validation of the Study 1 findings. It was based on

a different sample and different methodology. In this vein, Study 2 permitted

the determination of whether conclusions regarding the CPS’ mediating role

converged when examined with different samples and methods. To the degree

that convergence occurs, confidence is gained in the validity of the conceptual

premises underlying the theory in question (Brewer & Hunter, 1989). Using

structural equation methodology, Study 2 examined the fit of three different

job characteristics models, each of which included a different role for the CPS

in the model: (1) the job characteristics model shown in Figure 1, which modeled

the CPS a complete mediators; (2) a job characteristics model that included

the CPS’ direct effects and indirect effects through the CPS on outcome

variables, thus testing the partial mediating role of the CPS; and (3) a job

characteristics model that excluded the mediating role of the CPS altogether,

thus modeling the majority of job characteristics model research. These three

models were compared to themselves and “best” and “worst” fitting reference

points (discussed below). For the reasons explained under the description of

Study I above, it was postulated that the model most representative of the data

would be the one in which the CPS possess a mediating role, and a role of

partial rather than complete mediation.

Hypothesis 4: The job characteristics model that includes the CPS

as partial mediators

will provide

the best explanation

of the

motivational processes underlying the job characteristics model.

STUDY I

Method

Sample

Data for Study 1 were collected from 188 geographically dispersed subjects

working for different offices of one organization located in the Southeast.

Subjects performed a variety of jobs, including management (15% of the

sample), professional counseling (72% of the sample), and secretarial and

administrative support (13% of the sample). The average age of the subjects

was 44 years, 55% of whom were males. Fifty-five percent of the subjects had

at least eleven years of experience with the organization. All subjects held high

school diplomas, and among them 85(ro had bachelors degrees and 66% had

master’s degrees.

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

286

RENN AND VANDENBERG

Measures

The data were collected through surveys, distributed to and completed by

the subjects at their work sites. The surveys were given to the subjects in a packet,

which also contained a letter of endorsement

from the organization’s

chief

executive

officer and a return envelope

addressed

to the researchers.

Participation

was voluntary, and the subjects were guaranteed their responses

would remain confidential. Of the surveys distributed (N-230) and returned,

188 were fully completed and usable, yielding a response rate of 82%.

Core job dimensions. The revised Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) was used

to measure live core job dimensions (Idaszak & Drasgow, 1987). The scales

and their internal consistency coefficients were: skill variety ((Y = .76), task

identity (a = .76), task significance (CX= .77), autonomy (CX= .79), and feedback

from the job (a = .74).

Critical psychological states. Scales from the original JDS were used to

measure the CPS (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). The scales and their alpha

coefficients were: meaningfulness

(a = .81), responsibility

((Y = .83), and

knowledge of results ((Y= .80).

Outcomes. Scales from the original JDS were used to measure general

satisfaction, internal work motivation, and growth satisfaction. The scales and

their alpha coefficients were: general satisfaction (CV= .85), internal work

motivation (a! = .90), and growth satisfaction (a! = .81).

Analysis

Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach for testing mediation hypotheses was

used to test Hypotheses

1 and 2. Their approach required estimating three

regression equations,

which we have labeled Steps 1, 2 and 3, for each

hypothesized mediated relationship. Step 1 required regressing the mediator on

the independent variable. Step 2 required regressing the dependent variable of

the independent variable. And Step 3 required regressing the dependent variable

on the independent variable and the mediator.

According to Baron and Kenny, support for mediation is provided if the

following conditions hold: (1) the first regression shows that the independent

variable affects the mediator;

(2) the second regression shows that the

independent variable affects the dependent variable; and (3) the third regression

shows that the mediator affects the dependent variable and the effect of the

independent variable on the dependent variable is lower in magnitude in the

third equation than in the second equation (1986, p. 1177). To provide support

for complete mediation, the independent variable must not affect the dependent

variable when the mediator is controlled.

Hypothesis 1 states that the CPS will possess a mediating role in the job

characteristics

model. Thus, support for Hypothesis 1 would be provided if:

(1) each core job dimension affects its hypothesized

CPS (e.g., skill variety

affects experienced meaningfulness) (Step 1); (2) each core job dimension affects

each outcome variable (e.g., skill variety affects internal work motivation) (Step

2); and (3) each CPS affects each outcome variable (e.g., experienced

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

CRITICAL

PSYCHOLOGICAL

STATES

281

meaningfulness affects internal work motivation) (Step 3). Further, the effect

of each core job dimension on each outcome variable must be lower in

magnitude when each theory-specified CPS is controlled (e.g., the effect of skill

variety on internal work motivation must be lower in magnitude when

experienced meaningfulness is controlled) (Step 2 vs. Step 3).

Hypothesis 2 states that the CPS will be partial rather than complete

mediators. To provide support for this hypothesis, the results of Step 3 must

show that each core job dimension affects each outcome variable when each

theory-specified CPS is controlled (e.g., skill variety must affect internal work

motivation when experienced meaningfulness is controlled).

Hypothesis 3 states that all three CPS will not be necessary to maximize

the explanation of outcome variance; however, the CPS will account for

significant amounts of outcome variance beyond the core job dimensions.

Arnold and House’s (1980) regression technique was used to test this hypothesis.

They tested the requirement that all three CPS are necessary by comparing the

amount of outcome variance explained by a regression equation including the

main effects of the CPS and the CPS’ three two-way interaction terms to the

amount of variance explained by a regression equation including the latter terms

plus the CPS’ three-way interaction term. To support this requirement, they

suggested that the regression equation that included the main effects of the CPS,

the CPS’ three two-way interactions, and the CPS’ three-way interaction term:

(1) should explain the greatest amount of variance in an outcome variable; and

(2) should have a significant partial regression coefficient representing the CPS’

three-way product term.

The second part of Hypothesis 3 states that the CPS will explain significant

amounts of outcome variance beyond the core job dimensions. To test this part

of Hypothesis 3, we compared the amount of outcome variance explained by

a regression equation that included the main effects of the core job dimensions

to the amount of outcome variance explained by a regression equation that

included the main effects of the core job dimensions and the CPS, the CPS’

three two-way interactions, and the CPS’ three-way interaction. If the CPS

contribute to the job characteristics model’s explanatory power beyond the core

job dimensions, the second regression equation that includes the CPS would

be expected to explain significantly greater proportions of outcome variance

than the regression equation that included only the main effects of the core

job dimensions.

Results and Discussion

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among all Study 1

variables are presented in Table 1. Hypothesis 1 states that the CPS will possess

a mediating role between the core job dimensions and outcome variables. The

test for Hypothesis 1 required the estimation of three regression equations. In

the first regression equation, each CPS was regressed on its hypothesized core

job dimension. To satisfy this part of the test (Step I), each core job dimension

must affect its hypothesized CPS in the first regression equation. The regression

results for Step 1 are shown in Table 2. As seen in Table 2, all the regression

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

1.17

1.22

5.22

4.77

Autonomy

1.30

1.18

5.38

5.59

Note:

47

34

30

36

40

53

26

41

28

&j

1

Deviations,

:‘:

46

32

51

47

57

35

57

..-

2

::

28

23

57

61

18

40

3

22

32

18

49

39

47

26

4

and Inte~~orrelations

15

11

13

34

-10

19

5

6

::

58

29

24

Among

26

35

14

49

-

7

31

37

29

8

Study I Variables

N = 188. Decimals omitted from correlation matrix. Correlations equal to r = ,151

are significant at p < .OS.

1.25

Task Identity

Task Significance

11. Job Feedback

10.

9.

7.

8.

.79

1.32

1.06

1.29

5.83

5.49

6.10

5.19

5.40

3.

4.

5.

6.

“5

h,

5

v1

SD

1.35

1.24

internal

Motivation

Meanin~ulness

Knowledge of Results

Responsibility

Skill Variety

1. General Satisfaction

2. Growth Satisfaction

M

4.89

4.17

Table 1. Means, Standard

p

E

*!

2

2

=;

s

:

;

8

25

45

-

9

42

IO

--

II

g

!z

?z

5

z!

d

$

ifi

z

289

CRITICAL PSYCHOLOGICAL STATES

Table 2.

Regression Results for Core Job Dimensions’Effects on Psychological States

Critical Psychological States

Core Job Dimension

Now

-

.53**

.62**

.E*

-

N = 188. Standardized

* p < ‘05; ** p < .Ol.

Table 3.

-

.40**

.17*

Skill variety

Task identity

Task significance

Autonomy

Job feedback

Knowledge

Responsibility

Meaningfulness

regression

coefficients

reported.

Dashes indicate

coeffkient

not estimated.

Regression Results for Core Job Dimensions’ Effects on Outcomes

Regression and Partial Regression Coefficients

for Core Job Dimensions’

Outcomes

Skill

Variety

Task

Identity

Task

Significance

Autonomy

Feedback

.31**

.50**

.27**

.27**

.28**

.14**

*44**

.55**

57**

.69**

.36**

.47**

.34**

.20**

.19**

General satisfaction

Growth satisfaction

Internal motivation

Note:

N= 188.

a Standardized

regression

* p < .05; ** p < .Ol.

coefficients

reported.

coefficients representing the core job dimensions’ main effects on their

hypothesized CPS were statistically significant. These results, therefore, satisfied

Step 1 of the test for mediation.

In the second regression equation, each outcome variable was regressed

on each core job dimension (Step 2). The Step 2 test required that each core

job dimension affect each outcome variable in the second regression equation.

The results for the Step 2 test are shown in Table 3. Findings showed that the

regression coefficients representing the five core job dimensions’ main effects

on general satisfaction, growth satisfaction, and internal work motivation were

all significant. These findings, thus, satisfied the Step 2 test for mediation.

In the third regression equation, each outcome variable was regressed on

each core job dimension and hypothesized mediating CPS (Step 3). The Step

3 test required that the CPS affect each outcome variable in the third regression

equation, and that the effects of each core job dimension be lower in magnitude

in the third versus the second regression equation. Table 4 depicts the results

for the Step 3 test. As seen in Table 4, all but one of the regression coefficients

representing the CPS’ main effects on general satisfaction, growth satisfaction,

and internal work motivation were significant. The one exception was the

nonsign~icant regression coefficient representing the effects of knowledge of

results effect on internal work motivation.

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

290

RENN AND VANDENBERG

Table 4.

Regression Results for Core Job Dimensions’ and CPS’ Effects on Outcomes

Outcomes

General

Satisfaction

Predictor

Growth

Satisfaction

Internal

Motivation

Skill variety

Meaningfulness

.08

.51**

.31**

.41**

.14**

.30**

Task identity

Meaningfulness

.20**

.51**

.20**

.50**

.09*

.34**

Task significance

Meanin~u~ness

.15**

.47*x

.31**

.39**

.19**

.26**

Autonomy

Responsibility

.53**

.29**

*64**

.33+*

.14**

.44**

Feedback

Knowledge of results

.I1

.39**

.18**

.45**

.17**

.Ol

Note:

N= 188.

*p

< .os;** p < .Ol.

The second part of the Step 3 test required that the partial regression

coefficients representing the core job dimensions’ main effects on the outcome

variables be lower in magnitude in the regression equations that controlled the

hypothesized CPS (shown in Tabie 4) than the regression coefficients obtained

from the regression equations that excluded the CPS (Step 2 regression results

shown in Table 3). A comparison of the partial regression and regression

coefficients (Table 4 vs. Table 3) revealed that the effects of the core job

dimensions on general satisfaction, growth satisfaction, and internal work

motivation were all lower in magnitude when the hypothesized CPS were

controlled. These findings satisfied the second part of the Step 3 test for

mediation. Combined, the results of the three regression equations satisfied all

three steps in the test for mediation. Except in the case of knowledge of results,

these findings provided support for Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 states that the CPS will be partial rather than complete

mediators of the core job dimensions-outcomes relations. The test for this

hypothesis related to the partia1 regression coefficients representing the core job

dimensions’ effects on the outcome variables when the theory specified CPS

were controlled (Table 4 regression results). Specifically, if the partial regression

coefficients representing the core job dimensions’ effects on the outcomes are

significant when the CPS are controlled, support for partial mediation is

provided. By contrast, if the partial regression coefficients are not significant

when the CPS are controlled, support for complete mediators is provided. As

shown in Table 4, thirteen of the fifteen partial regression coefficients were

significant after the theory-specified CPS were controlled. Two exceptions were

the partial regression coefficients representing the direct effects of skill variety

and feedback on general job satisfaction. Aside from these two exceptions, the

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

CRITICAL PSYCHOLOGICAL STATES

Table 5.

291

Outcome Variance Explained by Job Dimensions

and Critical ~sychologic~ States

&for Outcome Variables

General

Satisfaction

Growth

Satisfaction

Internal

Motivation

Five core job dimensions

.31

.56

.29

M, R, K, M X R, M X K, R X IL”

.43

.63

.51

M, R, K, M X R, M X K, R X K,

MXRXK”

.43

.63

.5f

Predictor

Note:

N = 188. All R2’s 0, < .Ol). M = experienced meaningfulness; R = experienced responsibility;

K = knowledge of results.

a Variables entered into regression equation after the five core job dimensions.

findings supported the hypothesis that the CPS are partial rather than complete

mediator variables.

Hypothesis 4 states that all three CPS will not be necessary to maximize

the explanation of outcome variance, and that the CPS will account for significant amounts of outcome variance beyond the core job dimensions. If the three

CPS are necessary to maximize the explanation of outcome variance, there

should be a significant R2 increment when the CPS’ three-way product term

is included in the regression equation containing the main effects of the core

job dimensions and the three CPS, and the CPS’ three two-way product terms.

Table 5 summa~zes the regression results for this test. As seen in Table 5, the

findings showed that the three-way product term did not increase the amount

of variance explained in general satisfaction, growth satisfaction, or internal

work motivation beyond the amount of variance explained by the regression

equation that included the main effects of the core job dimensions, the CPS,

and the CPS’ two-way interaction terms. Further, the partial regression

coefficients representing the CPS’ three-way interaction te2ms in these

regressions were all nonsigni~cant (results available from the authors).

The regression results shown in Table 5 also indicated that the CPS

explained significant amounts of variance in general satisfaction, growth

satisfaction, and internal work motivation beyond the core job dimensions. As

expected, the five core job dimensions alone accounted for significant amounts

of variance in these outcome variables. However, the propo~ion of variance

accounted for in all three outcome variables increased sign~cantly when the

three CPS were added to the regression equations. Specifically, adding the three

CPS to the regression equations increased the proportion of explained outcome

variance in general job satisfaction by 13% (Fj,179=: 14.4, p < .Ol), growth

satisfaction by 12% (F 3,t79= 22.5, p < .Ol), and internal work motivation by

22% (F3,179= 22.5, p < .Ol). These findings, thus, provided support for

Hypothesis 3.

To summarize, the findings from the Baron and Kenny (1986) approach

provided support for Hypotheses 1 and 2. In accordance with the job

JOURNAL OF MANAGEME~,

VOL. 21, NO. 2,199s

RENN AND VANDEN3ERG

292

characteristics model, the findings indicated that the core job dimensions related

well to their specified CPS and that the CPS related well to general job

satisfaction, growth satisfaction, and internal work motivation. Further,

experienced meaningfulness completely mediated the skill variety-general job

satisfaction relationship, and knowledge of results completely mediated the

feedback-general satisfaction linkage. By constrast, the findings indicated that

meaningfulness, responsibility, and knowledge of results were partial mediators

of the remaining hypothesized relations between the core job dimensions and

general job satisfaction, growth satisfaction, and internal work motivation. In

addition, the feedback-internal work motivation relationship was not mediated

by knowledge of results. Finally, the endings provided support for Hypothesis

3. All three CPS were not necessary to maximize the explanation of outcome

variance, and the CPS accounted for significant amounts of outcome variance

beyond the core job dimensions. Study 2 was designed to further examine the

Study 1 finding that the CPS were partial mediators of the core job dimensionsoutcomes relations.

STUDY 2

Methods

Sample and Data Cdection

The Study 2 sample consisted of 90 policy processing and customer service

employees of a major Southeastern insurance company. The subjects

represented 100% of the employees in this functional area. The subjects

performed three categories of jobs, namely management and supervision (N

= 8), policy processing and issuing (N = 70), and customer service ( N = 12).

Median age and years of education were 28.5 and 12 years, respectively. Seventythree percent of the sample was female. Sixty-four percent of the subjects had

been in their current jobs two years or less, and 51% had been with the

organization five years or less.

Measures

The Study 2 data were collected through surveys. Subjects completed the

surveys in large group sessions away from the work area and were guaranteed

anonymity of their responses through minimum identification requirements.

Core job dimensions. Scales from the revised Job Diagnostic Survey

(JDS) were used to measure five core job dimensions (Idaszak & Drasgow,

1987). The measures and their internal consistency reliabilities were: (1) skill

variety ( a! = .76); (2) task identity (a = .76); (3) task significance (o = .77);

(4) autonomy (a, = .90); and (5) feedback from the job (Q = 69).

Critical psychological states. For the CPS, the original JDS items were

used (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). The scales and their internal consistency

coefficients were: (1) meaningfulness (a = .81), responsibility ((u = .83), and

knowledge of results (a = 80).

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2. 199.5

CRITICAL PSYCHOLOGICAL STATES

293

Outcome variables. Two outcome measures from the original JDS

(Hackman & Oldham, 1980) were completed by respondents: (1) general job

satisfaction ((Y= .85); and (2) internal work motivation (a = .90). In addition,

job search intentions were assessed by having employees respond with l=(O

to 20%), 2=(21 to 40%), 3=(41 to 60%), 4=(61 to 80%), or 5=(81 to 100%)

to the question: “What is the probability that you will be involved in a search

for a job outside the company during the next 12 months?”

Model Development

and Analysis

Based on Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988)“two-step" approach (discussed briefly

below) for evaluating competing theoretical structural models, five nested “job

characteristics models” were estimated using LISREL VII (Joreskog & S&born,

1989). Differences among the nested models are summarized in Table 6. Model I

represented the least restricted or saturated structural model. For the saturated

model, all possible paths among this “job characteristics model’s” components were

estimated. The paths from skill variety, for example, to all three CPS were estimated,

as were the paths from skill variety to all of the outcome variables. The paths from

the remaining core job dimensions to the CPS and outcomes were all freed in a

similar manner. This model was estimated to provide goodness of fit indices

(discussed below) for the best possible fitting structural model.

Model II represented the next least restricted model in the sequence. This

model estimated the core job dimensions’ direct and indirect effects on personal

and work outcomes. Direct effects were estimated by freeing the paths from

the core job dimensions directly to the personal and work outcomes. The

indirect effects were estimated by freeing the paths from the core job dimensions

to their speczjied CPS and freeing the paths from the CPS to the outcomes.

Model II was based on Hackman and Oldham’s (1976) finding and the Study

1 finding that the CPS may be partial rather than complete mediator variables.

Model III represented the original job characteristics model and the next

model in the sequence (see Figure 1). For Model III, only the core job

dimensions’ indirect effects on personal and work outcomes were estimated.

The paths from the core job dimensions to their specified CPS were freed, as

were the paths from the CPS to the outcome variables.

Model IV excluded the mediating role of the CPS from the job characteristics model. Only the core job dimensions and the outcome variables were

Table 6.

Model

I

II

III

IV

V

Note:

Study 2 Model Differences

Structural Specifications

Paths among all job characteristics model components.

Paths from: (a) CJD to outcomes; (b) CJD to CPS; (c) CPS to outcomes.

Paths from: (a) CJD to CPS; (b) CPS to outcomes.

Paths from CJD to outcomes.

Structural null model.

CJD = core job dimensions; CPS = critical psychological states.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT, VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

294

RENNANDVANDENBERG

included in this model. Paths from the core job dimensions to the outcome

variables were estimated. Model IV was based on job characteristics

model

research that has excluded the mediating role of the CPS and estimated only

the core job dimensions’ direct effects on personal and work outcomes.

Lastly, Model V represented the structural null or most restricted model

in the sequence. For Model V, all paths among the job characteristics model’s

components were fixed to zero.

Covariance matrices and information

about each scale’s reliability and

variance were used as input for the LISREL program (Podsakoff,

Williams

& Todor, 1986; Renn, 1989). Two-stage least squares and maximum-likelihood

procedures yielded initial and final parameter estimates, respectively. The latentto-manifest parameter for each variable was fixed to the square root of the

reliability (internal consistency coefficients) for each measure, and the value one

minus the reliability times a variable’s variance was used to represent residuals.

This technique provided the means to incorporate measurement error into the

analysis prior to estimating the structural models.

Models Comparison

Sequential Chi-Square Difference Tests (SCDTs).

SCDTs were used to

compare statistically the fit of the five nested structural models. Specifically,

the five models were compared via a decision-tree framework similar to a

framework provided by Anderson and Gerbing (1988, p. 420). In general, the

framework required a sequential a priori comparison of the chi-square values

and associated degrees of freedom of two models-one

more restricted than

the other. The models were compared in an priori sequence to determine if

restricting a set of parameters to equal zero statistically reduced a model’s power

to account for covariance among the model’s constructs (Anderson & Gerbing,

1988; Bentler & Bonett, 1980; James et al., 1982; Williams & Hazer, 1986). The

null hypothesis for each paired models comparison was no significant difference

between the chi-square values of the least and more restricted models. A rejected

null hypothesis, as indicated by the SCDT, provides statisticaz support for the

least restricted of the two models. Anderson and Gerbing indicated, however,

that statistically significant differences between models may be found during

these comparisons even when there are trivial differences between the amounts

of construct

covariance

explained by each model. Thus, they suggested

comparing the models on a practicaZ as well as statistical basis. To this end,

we used the parsimonious fit index to judge the practical significance of each

model (James et al., 1982). These as well as other fit indexes used to judge the

fit of the five models are described below.

LISREL ‘s Goodness of Fit Indexes. The overall fit of each model to the

data was assessed with LISREL’s chi-square statistic, Goodness of Fit Index

(GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), and Root Mean Square

Residual (rmsr). In general, a nonsignificant chi-square, large GFI and AGFI,

and small rmsr values are associated with better fitting models.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

CRITICAL

PSYCHOLOGICAL

STATES

295

~~crerne~~aZ

Fit Index (IFI). The IF1 was used to judge the relative fit

of competing models to the data in relation to the structural null model (Bollen,

1989). The IF1 has the same advantage of accurately reflecting model fit as the

normed fit index (Bentler & Bonett, 1980) and has the additional advantages

of performing better with small samples and having a smaller sampling variance

(Bentler, 1990). The range of IF1 values is generally between O-l, with larger

values reflecting better fitting models.

Parsimonious Fit Index (PFI). The PFI was used to compare the

practical significance and efficiency of the five models (James et al., 1982). The

PFI represents a model’s ability to explain construct covariance given the

number of freely estimated parameters. Even when there is statistical support

for a least restricted model (i.e., a model with more freely estimated parameters),

the more restricted model may be judged superior from a practical standpoint

based upon a superior PFI value. A superior relative PFI indicates that a model

is more parsimonious or efficient than a competing model in explaining an

acceptable amount of construct covariance (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988, p. 421).

Signifkance of Parameter Estimates. The significance of the parameter

estimates for each model was determined by a statistic approximating the tdistribution. Estimates with t-values of 2.0 or greater are significant at or beyond

the p < .05 level.

Descriptive statistics for the manifest variables are shown in Table 7. The

goodness of fit indexes for Models I-V are presented in Table 8. As seen in

Table 8, of the theoretical models examined (Models II-IV), the two models

that included the CPS provided better fits to the data than did the model that

excluded the CPS (Model IV). In brief, Models II and III had the smallest chisquare and rmsr values, and the largest GFIs, AGFIs, IFIs, and PFIs. Both

models also had the largest ratio of the number of significant obtained to

hypothesized path coefficients.

The models were subjected to an a priori series of SCDTs: (1) Model III

(job characteris tics model with CPS) versus Model I (fully saturated model),

~2~~~~~~~

= 294.6,~ < .Ol; (2) Model IV (CPS excluded) versus Model III, x2&rffi)

= 77.1, p < -01; (3) Model III versus Model II (core job dimensions direct and

indirect effects through CPS), X2dirrtr>)

= 274.0,~ < .Ol; and (4) Model II versus

Model 1, X*&K(~)

= 20.5, p < .Ol.As expected, the SCDTs indicated that Model

I (fully saturated model) provided a statistically better fit to the data than did

the other models. More important, however, were the results for the theoretical

models (Models II-IV). The results indicated that, next to the fully saturated

model (Model I), Model II provided the best fit to the data. Further, Model

II’s PFI value indicated that it was the most parsimonious of all models,

including Model I. Thus, from a statistical and practicaZ standpoint, the model

comparisons provided the greatest support for Model II.

Comparing Model II directly to Model III (original job characteristics

model) provided additions support for Model II. Specifically, Model II’s

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2,1995

1.8

4.1

5.4

4.8

5.0

4.8

3.9

3.1

5.3

4.4

4.3

1. Search intentions

General satisfaction

3. Internal motivation

4. Meaningfulness

5. Responsibility

6. Knowledge of results

7. Skill variety

8. Task identity

9. Task significance

10. Autonomy

11. Job feedback

Correlations

greater than .21 are significant

NCHP: N = 90. Decimals omitted from correlation

2.

M

-24

-02

-24

-01

-25

-01

-10

-14

-10

-08

I

47

45

36

22

25

06

17

38

27

2

Deviations,

matrix.

at p < .05 (one-tailed).

1.1

0.9

1.1

1.0

1.1

1.6

1.6

1.4

1.7

1.3

1.2

SD

Means, Standard

Variable

Table 7.

16

22

16

07

03

07

17

14

3

51

16

55

32

49

45

27

4

and Intercorrelations

33

36

40

26

42

27

5

II

14

07

19

52

6

12

61

54

26

7

04

35

21

8

for Study 2 Variables

43

29

9

32

10

-

I1

CRITICAL

PSYCHOLOGICAL

Tabie 8.

297

STATES

Goodness of Fit Indexes

Fit Indexes

df

xz

P

rmsr

GFI

AGFI

IFI

PFI

Paths

19.4

40.0

314.0

391.1

.20

.05

.OOl

IV

::

36

37

.06

.09

.14

.33

.95

.92

.80

.68

.80

.I4

.62

.29

1.0

.96

.43

.27

.32

.43

.32

-21

18/39

16129

6/ 14

2115

Null

61

520.5

.44

.64

.23

-

-

Model

I

II

III

.OOl

.OOl

-

Nore: N= 90. df= degrees of freedom; x2 = chi square; rmsr = root mean square residual; GFI = goodness

of fit index; AGFI = adjusted goodness of fit index; IFI = incremental fit index; PFI = parsimonious

fit index; Paths = ratio of significant obtained to predicted parameters.

Table 9.

Path

(I) SV-M

(2) TI-M

(3) TS-M

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

(8)

(9)

(10)

(11)

(12)

(13)

(14)

(15)

A-R

F-K

M-S

M-IM

M-S1

R-S

R-IM

R-S1

K-S

K-IM

K-S1

sv-s

Nore:

Obtained Parameter Estimates for Model II

Estimate

Path

Estimate

.08

.40*

.58*

.51*

.63*

.75*

.03

-.54*

.16

.08

-.I0

.06

.07

-.42*

.48*

(16) SV-IM

(17) sv-SI

(18) TI-S

(19) TI-IM

(20) TI-SI

(21) TS-S

(22) TS-IM

(23) TS-SI

(24) A-S

(25) A-IM

(26) A-SI

(27) F-S

(28) F-IM

(29) F-S1

3.30*

-.22*

.78*

.58*

-.23

1.25*

2.28*

-.62*

.52”

.36

-.I7

.49*

.56*

-.25

Each path combination

should be read as “from” one variable “to” the other.

SV = skill variety; TI = task identity; TS = task significance; A = autonomy; F = feedback; M

= meaningfulness;

R = responsibility;

K = knowledge of results; S = general satisfaction; IM =

internal motivation; SI = search intentions.

Estimates greater than one due to scaledifferences.

* p < .05.

goodness of fit indexes were superior to those of Model III. And according

to Model II’s PFI value, its superior fit over Model III was not due to relaxing

parameters (James et al., 1982). The SCDTs (discussed above) also showed that

Model II provided a statistically better fit to the data than does Model III. Model

II also had a higher ratio of the number of significant obtained to hypothesized

path coefficients than does Model III. Table 9 shows the LISREL estimates

of the path coefficients for Model II.

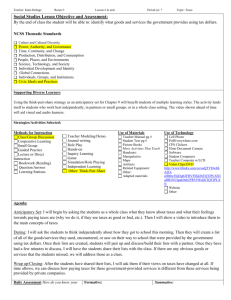

In summary, the goodness of fit indexes associated with Models I-V

indicated that the two job characteristics models that included a mediating role

for the CPS provided better fits to the data than did the model that excluded

the CPS’ mediating role. Of the two models including a mediating role for the

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

RENN AND VANDENBERG

298

..................

...........

.

,_.’

Note:

N = 90. Ali paths shown are significant at or beyond p < .05. Solid paths represent significant paths

from original job characteristics

model. Dotted paths represent significant paths representing the

core job dimensions’ direct effects on persona1 and work outcomes.

Figure 2. Best-Fitting Job Characteristics Model

CPS, the model comparisons and the ratios of the number of significant

obtained to hypothesized path coefficients provided their greatest support for

the job characteristics model that represented the CPS as partial rather than

complete mediator variables. Thus, the Study 2 results validated the Study 1

finding that the CPS were partial rather than complete mediators of the core

job dimensions-outcomes relations. Figure 2 depicts the job characteristics

model (Model II) that received the greatest support in Study 2.

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

CRITICAL

PSYCHOLOGICAL

STATES

299

STUDY 1 AND STUDY 2

General Discussion

The primary question driving this research was: Do the CPS make a

significant contribution to the job characteristics model’s ability to explain basic

work processes, or are the CPS an unnecessary component of the job

characteristics

model whose exclusion would make the theory more

parsimonious? With regard to this underlying question, the findings from both

studies indicated that the CPS contributed significantly to the job characteristics

model’s explanatory power, and thus, should not be excluded from the theory.

Although they supported the inclusion of the CPS, the findings did not support

the CPS’ inclusion as was originally hypothesized and depicted in the job

characteristics model. The findings did not support the requirement that all three

CPS need to be experienced to maximize the explanation of work outcomesa finding that was consistent with our hypothesis and with the findings of past

research (Arnold & House, 1980; Hackman & Oldham, 1976). In addition, the

findings did not support the CPS’ role as complete mediators of the core job

dimensions-outcomes relations (as depicted in the job characteristics model).

Findings from both studies demonstrated that the core job dimensions had

direct and indirect effects (through the CPS) on the outcome variables. This

finding is subject to at least two interpretations, both of which have implications

for future job characteristics model research.

First, the core job dimensions’ direct effects on personal and work

outcomes could represent an individual’s immediate affective response to a job

stemming from the momentary activation of certain cognitions (Feldman &

Lynch, 1987). Namely, researchers note (e.g., Vandenberg & Seo, 1992) that

certain stimuli in the work environment (in this case job dimensions) cause both

an immediate affective response to that stimuli, and the stimulation of cognitive

processes that reflect a more piecemeal careful assessment of the implications

the stimuli have for the individual (see also, Lord, 1991). This more careful

assessment is not immediate but in the long run causes an individual to alter

his or her immediate reactions to the stimuli. Within this perspective, the core

job dimensions direct effects may represent an individual’s immediate affective

reaction to a job. By contrast, the core job dimensions’ indirect effects through

the CPS may represent an individual’s more thought out and long term

assessment of the job. Testing this interpretation of the core job dimensions

direct and indirect effects goes beyond the limits of the present cross-sectional

data. However, this interpretation could be tested by collecting multiple waves

of measures in a longitudinal study. With such longitudinal data, researchers

could test this interpretation by analyzing the core job dimensions’lagged effects

(through the CPS) apart from their immediate effects on personal and work

outcomes.

Second, that meaningfulness, responsibility, and knowledge of results did

not explain the core job dimensions’ total effects on the present outcomes leaves

room for other “psychological states” to mediate these relations. Gardner and

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

300

RENN AND VANDENBERG

Cummings (1988), for example, hypothesize that activation theory may explain

why core job dimensions influence personal and work outcomes (see also

Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Scott, 1966). Drawing from activation theory,

Gardner and Cummings postulate that enriched or “high impact” jobs (as

reflected in higher levels of the core job dimensions) may stimulate higher

activation levels (potential “CPS”), which, in turn, lead to positive affect and

behavioral efficiency (better personal and work outcomes). By contrast,

monotonous or “low impact” jobs may depress activation levels, which, in turn,

lead to negative affect and lower performance. Fox and Feldman (1988) provide

some support for activation level as a potential mediating CPS. They found

that arousal {operation~ized as attention state) mediated the relationship

between skill variety, task identity, and autonomy and general job satisfaction,

effort, and performance.

Fried and Ferris’ meta analysis led them to also suggest that other

psychological states unspecified by the job characteristics model may mediate

the relationship between the core job dimensions and performance (1987, p.

312). They found that, of the five core job dimensions, task identity and job

feedback had the strongest associations with performance. However, they also

found that experienced meaningfulness and knowledge of results-the

hypothesized mediators of these two job dimensions, were not related to

performance. Since a hypothesized mediator of the relationship between an

independent and a dependent variable must affect the dependent variable (Step

3 of the Baron and Kenny approach described above), Fried and Ferns’ findings

appear to indicate that experienced meaningfulness and knowledge of results

do not mediate, respectively, the relations between task identity and job

feedback and performance.

Thomas and Velthouse (1990) identified “CPS” (they labeled “task

assessments”) unspecified by the job characteristics model that may mediate

the relations between these core job dimensions and performance. They

theorized that perceived impact (Abramson, Seligman & Teasdale, 1978),

competence (Bandura, 1977), and choice (decharms, 1968) mediate the

relationship between interventions (e.g., job design or redesign) and behavior

(e.g., motivation and performance). Of these three potential CPS, it seems

plausible that perceived impact could mediate the relationship between task

identity and pe~ormance, and that competence may mediate the relationship

between job feedback and performance. Perceived impact represents “the degree

to which behavior is seen as ‘making a difference’ in terms of accomplishing

the purpose of the task” (Thomas & Velthouse; 1990: p. 672). Task identity

may prompt perceived impact because it represents the degree to which a job

requires the completion of an entire piece of work. Specifically, successful

completion of an entire task without assistance from others would be expected

to result in the belief that one’s work behaviors made the sole and significant

difference (i.e., had high impact on) in the quality and quantity of work output.

In turn, high perceived impact would be expected to lead to increased

motivation and improved work performance (Abramson et al., 1978).

Competence-a

concept similar to Bandura’s (1977) concept of self-efficacy,

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

CRITICAL

PSYCHOLOGICAL

STATES

301

represents “the degree to which a person can perform task activities skillfully

when he or she tries”(Thomas & Velthouse, 1990, p. 672). Both the development

of competence and the knowledge of one’s competence may derive from job

feedback. Job feedback provides direct and clear information about work

effectiveness (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). Thus, positive feedback stemming

from high work effectiveness should lead to the belief that one can perform

a task effectively or competently. The belief that one is competent at a task,

in turn, has been linked to greater effort and persistence during task performance

(Bandura, 1977). Examining the potential mediating effects of perceived impact

and competence between task identity and job feedback and performance may

lead to a clearer understanding of why these two job dimensions relate more

strongly to performance than do skill variety, task significance, and autonomy,

job dimensions that may not prompt these “CPS.” In sum, despite which of

these two interpretations future research demonstrates to be the more accurate,

it is clear from the present findings that more research is needed on the

motivational underpinnings of the job characteristics model to provide a better

understanding of how and why job dimensions affect personal and work

outcomes.

Although based on two diverse samples and methodologies, the present

findings are not without limitations. Some may view the exclusion of the growth

need strength moderator as a limitation. As noted earlier, however, studies

indicate that the relations among the job characteristics model’s components

can be adequately tested without the growth need strength moderator (Graen

et al., 1986; Johns et al., 1992; Teigs et al., 1992). Further, the Fried and Ferris

(1987) meta-analysis demonstrates that growth need strength’s moderating

effects have been largely artifactual, except in the case of the core job

dimensions-performance relationship. Nonetheless, the present findings would

be strengthened if they were replicated by future research that included the

growth need strength moderator. The present findings were derived from crosssectional research designs and paper-and-pencil measures. Common method

variance, thus, may have inflated the present results. Glick, Jenkins & Gupta

(1986), however, show that core job dimensions have significant associations

with outcomes after common method variance is controlled. The Fried and

Ferris (1987) meta-analysis suggests that common method variance is not as

much of a threat to job characteristics model research as previously believed.

Further, to test for the potential effects of common method variance in Study

2, we ran a Hogan and Mar-tell (1987) test (see also, Vandenberg & Scarpello,

1990). This test revealed that a single-factor model-representing

common

method variance, produced a poorer tit to the data than did the fully-saturated

model (Model I) and the target model (Model II as shown in Figure 2) (results

available from the authors upon request). Therefore, common method variance

does not appear to be a likely alternative explanation for the present findings

supporting the partial mediating role of CPS.

Data in Study 2 were collected in partial fulfillment of the

1st author’s dissertation requirements. The authors wish to thank Emin

Acknowledgment:

JOURNAL

OF MANAGEMENT,

VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

302

RENN AND VANDENBERG

Babakus, Rabi Bhagat, John Miner, and Lynn M. Shore for their assistance

in preparing this manuscript. The first author thanks Paul M. Swiercz for

assistance in collecting the Study I data. We are also greatly indebted to and

thank three anonymous reviewers for their invaluable input and patience.

References

Abramson, L.Y., Seligman, M.E.P. & Teasedale, J.D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and

refo~ulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87: 19-74.

Anderson, J.C. Br Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural equation mode~ng in practice: A review and

recommended two-step approach. ~syc~o~ogicQi Rulietin, 103: 41 l-123.

Arnold, H.J. & House, R.J. (1980). Methodological and substantive extensions to the job characteristics

model of motivation. Organizationat Behavior and Human Performance, 25: 161-183.

Bacharach, S. (1989). Organizational theories: Some criteria for evaluation. Acctdemy of Manugemenr

Review, 14: 496-515.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. ~~~c~ofog~cu~Review. 84:

191-215.

Baron, R.M. & Kenny, D.A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction statistical considerations.

Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology,

21: 1173- 1182.

Bentler, P.M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107: 238-246.

Bentler, P.M. & Bonett, D.G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance

structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88: 588-606.

Beriinger, L., Glick, W.H. & Rodgers, R.C. (1988). Job enrichment and perform ante improvement. Pp.

219-254 in John P. Campbell, Richard J. Campbell Br Assoc. (Eds.), Productivity in organizations.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ballen, K.A. (1989). Srrucrurol equa&~~~ modeling with luzent vuriubles. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Brewer, J. & Hunter, A. (1989). Mu~zimethod research: A synthesis of styles. Newbury Park: Sage.

Champoux, J.E. (1991). A multivariate test of the job characteristics theory of work motivation. Journal

of Organizational Behavior, 2: 43 l-446.

decharms, R. (1968). Personal causation: The unernal affective determinunts of behavior. MA: AddisonWesley.

Feldman, J.M. & Lynch, J.G. (1988). Self-generated validity and other effects of me~urement on beliefs,

attitude, intention, and behavior. Journuf of A&ted Psychology, 73: 421435.

Fox, S. & Feldman, G. (1988 0. Attention state and critical psychological states as mediators between job

dimensions and outcomes. Human Relations, 41: 229-245.

Fried, Y. & Ferris, G.R. (1987). The validity of the job characteristics model: A review and meta-analysis.

Personnel Psychology,

40: 281-322.

Gardner, D.G. &Cummings, L.L. (1988). Activation theory and job design: Review and reconceptualization.

Pp. 81-122 in B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizutionaf behavior, Vol. 10.

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Gliek, W.H., Jenkins, G.D. & Gupta, N. (1986). Method versus substance: How strong are the underlying

relationships between job characteristics and attitudinal outcomes? Academy of~~nugement Journal,

29: 441-96-4.

Graen, G.B., Scandura, T.A. & Graen, M.R. (1986). A field experimental test of the moderating effects of

growth need strength on productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71: 484-491.

Griffin, R.W. (1991). Effects of work redesign on employee perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Academy

of ~an~gemeni

Journal, 34: 425-435.

Griffin, R.W., Welsh, A. & Moorhead, G. (1981). Perceived task characteristics and employee performance:

A literature review. Academy of Management Journal, 6: 655-664.

Hackman, J.R. & Lawler, E.E. (1971). Employee reactions to job characteristics. Journal of Applied

Psychology,

55: 259-286.

Hackman, J.R. KcOldham, G.R. (1975). Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 60: 159-170.

~.

(1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and

~.

Human ~e~ormanee* 16: 250-279.

(1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Harris, M.M. L Schaubroeck, J. (1990). Confirmatory modeling in organizational ~havior/human

management: Issues and applications. Journal of Management, 16: 337-360.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT, VOL. 21, NO. 2, 1995

resource

CRITICAL PSY~~~L~G~~AL

STATES

303

Hogan, E.A. 62 MarteII, D.A. (1987). A confirmatory structuraI equation analysis of the job characteristics

model. ~~n~z~r~o~al Behavior and N~man De&ion Processes, 39: 242-263Sdaszak, JR, &

Drasgow, F. (1987). A revision to the Job Diagnostic Survey: Eli~nat~on of measurement artifact.

Journal of Apphed Psychology. 72: 69-74.

James, L.R. (1980). The unmeasured variable problem in path analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology,

65: 415-421.

James, L.R. & Brett, J.M. (1984). Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 69: 307-321.

James, L.R., Mulaik, S.S. & Brett, J.M. (1982). Causalanalysis: Assumptions, models, and data Beverly

Hills: Sage.

Johns, G.J., Xie, J.L. 8r Fang, Y. (1992). Mediating and m~erating effects in job design. ~o~r~u~ of

~a~gern~t~ 18: 657-676.

JBreskog, KG. & S@bom, D. (i989). LiSREL 7 user5 reference guide, Chicago: Scientific Software, Inc.

Kanfer, R, (1991). motivation theory and industrial and orga~ationa~ psychoio~. Pp_ 125-170 in M.

Dunnette & L. Hougb (Eds.) handbook of~d~tr~a~and organizationalpo~ogy,

Palo Ahu, CA:

Consulting P~ycho~o~s~ Press.

Loher, B.T., Noe, R.A., Moeller, N.L. 6%FitzgeraId, M.P. flSS5). A meta-abyss

of the ~~at~o~b~p of

job characteristics to job satisfaction, JownuI of A&ted Psychology, 10: 280-289.

Lord, R. (1991). Cognitive theory in industrial and organization& psychology. Pp. 1-62 in M. Dunnette

& L. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrialand organizationalpsychology. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting

Psychologists Press.

Marsh, H.W., Balla, J.R. & McDonald, R.P. (1988). Goodness-of-fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis.

Psychological Rulletin, 103: 391410.

Miner, J.B. (1980). Z%eories of organizational behavior. Hinsdale, IL: Dryden Press.

Pierce, Y.L., Dunham, R.B. & Blackburn, R.S. (1979). Social systems structures, job design, and growth

need strength: A test of a congruency model. Academy of ~a~gern~~t Journak 22: 223-240.

Podsakoff, P.M., W~~~~arns,

L.J. & Todor, W.D. (3986). Effects of fo~~tion

on alienation among

professionals and nonprof~sion~s, Academy of ~anagemenr Journal, 29: 820-831.

Renn, R. W. (~989}.A holistic evaluation oft~e~~ ~hara~ter~t~~s

modek A lon~.~~~a~st~~turafegtratian

anah&. ~npu~~sbed doctoral disse~atio~, Georgia State ~nive~ty~ Atlanta, Georgia.

Scott, W.E. (1966). Activation theory and task design, ~gu~~~~o~~~ ~~~v~or and Human Perform~~e,

if:3-30.

Tiegs, R.B., Tetrick, L.E. &t Fried, Y. (1992). Growth need strength and context satisfactions as moderators

of the relations of the job characteristics model. Journaf of management, 18: 575-594.

Thomas, K.W. & Velthouse, B.A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” modei of

intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review, 15: 666-681.

Tucker. L.R. & Lewis, CA. (1973). A rehabihtv coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analvsis.

.

Psychometricka, 38: I-10.

Vandenberg, R.J. & Scarpello, V. (1990). The matching model: An examination of the pracesses underlying

realistic job previews. Journal of Apphed Psvchologv, 75: 60-67.

Vandenberg, R:J., Self, R.M. & Seo, J.-H. (i994). A ~~tic~~xam~nation of the intemaiization, ident~cation,

and compliance comm~tmeut measures. fournat of~anagement, 20: 123-140.

Vanden~rg, R.J. 8c Sea, J.H. (f992). Placing recruiting electiveness in perspective: A cognitive explication

of the job&&e

and organi~tion~~ot~

period. F&ran Resource ~a~gerne~t Review, 2: 23%

273.

Wall, T.D., Ciegg, C.W. & Jackson, P.R. (19?8}. An evaluation of the job characteristics model. Journal

af ~~~Pat~ona~ Psy~ho?ogy,JI: 183-1%.

Wiliiams, L.J. & Hazer J.T. (i986). Antecedents and consequences ofsatisfactionand commitment in t~ov~r

models: A reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods. Journal of Apphed

Psychology, 71: 219-231.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMEh~,

VOL. 21, NO. 2,1995