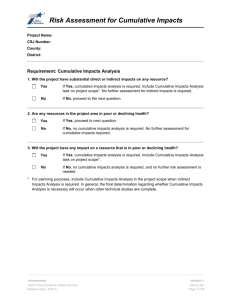

Legal Sufficiency Criteria for Adequate Indirect Effects and

advertisement