Examiners' Report January 2014

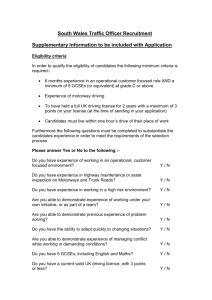

advertisement

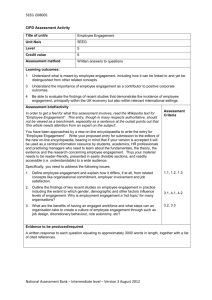

GCE EXAMINERS' REPORTS ENGLISH LITERATURE AS/Advanced JANUARY 2014 © WJEC CBAC Ltd. Grade boundary information for this subject is available on the WJEC public website at: https://www.wjecservices.co.uk/MarkToUMS/default.aspx?l=en Online results analysis WJEC provides information to examination centres via the WJEC secure website. This is restricted to centre staff only. Access is granted to centre staff by the Examinations Officer at the centre. Unit Page LT1 1 LT4 5 © WJEC CBAC Ltd. ENGLISH LITERATURE General Certificate of Education January 2014 Advanced Subsidiary LT1: Poetry and Drama Principal Examiner: Dr Jennifer McConnell General Comments We are now into the sixth year of the specification and it is pleasing to see that most candidates are aware of the requirements of the paper. However, there are still some issues that need to be addressed and it is hoped that the points outlined in this report will be of use to teachers preparing for the May session. Section A: Poetry post-1900 AO1 As in previous years, there is still evidence of a lack of planning in a number of cases. Candidates have 1 hour 15 minutes to spend on Section A and it is strongly advised that they spend at least 15 minutes planning. 1 hour is more than enough time to write a strong essay, and essays that are well planned will be more likely to be focused and relevant. There are still some candidates who are taking a chronological approach to poems. Working through the poems stanza by stanza is not an effective approach and often results in a lack of relevance. AO2 A significant minority of candidates are still embedding quotations without discussing how meaning is created. As has been stated in previous reports, these candidates often scored highly on AO1 (concepts) but did less well on AO2. Almost all candidates would benefit from closer focus on how meaning is created. AO3i As in previous sessions, the strongest responses used the partner text as a lens through which to discuss the core text. However, some candidates are still discussing the partner text in isolation from the core text. If no link is made to the partner text, the candidate will score 0/5 for this AO. If the only link is a basic link through the question (e.g. Abse also writes about death) then the maximum a candidate will receive is 1/5. AO3ii There are still some cases where candidates do not include any readings at all or even any tentative language (such as ‘perhaps’). As noted in last summer’s report, in some cases candidates use ‘signpost’ phrasing such as ‘some critics might argue’ or ‘another reading could be’ (which in itself is good practice), but then go on to offer the same reading, only worded differently. It is important that candidates offer different readings. © WJEC CBAC Ltd. 1 Notes on Questions T.S. Eliot: Selected Poems (Core text) (Prufrock and Other Observations, The Waste Land, The Hollow Men, Ariel Poems) W.B. Yeats: Selected Poems (Partner text) There was a range of responses to both questions. ‘Prufrock’ and ‘Portrait of a Lady’ proved useful choices for Question 1 (men). However, some candidates struggled to keep focus on key words in Question 2 (sorrow and suffering) often asserting that Eliot and Yeats were writing about sorrow and suffering rather than providing evidence, or else drifting from the question completely. Philip Larkin: The Whitsun Weddings (Core text) Dannie Abse: Welsh Retrospective (Partner text) Question 4 (death) was popular and candidates enjoyed writing about this topic. Question 3 (everyday experiences) was interpreted quite broadly in some cases, but any valid interpretation was accepted by examiners. Sylvia Plath: Poems Selected by Ted Hughes (Core text) Ted Hughes: Poems Selected by Simon Armitage (Partner text) Question 5 (strong emotions) allowed candidates to write on a number of emotions including grief and love, while Question 6 (place) included relevant responses on both indoor places (such as the hospital in ‘Tulips’) and outdoor places (such as the moors in ‘Wuthering Heights’). Carol Ann Duffy: Selected Poems (Core text) (Standing Female Nude, The Other Country, The World’s Wife) Sheenagh Pugh: Selected Poems (Partner text) Question 6 (women/girls) was by far the more popular question and candidates clearly enjoyed writing on this topic. Some candidates offered confident discussions about the objectification of women and the male gaze in ‘Standing Female Nude’ and ‘Eva and the Roofers’. Seamus Heaney: New Selected Poems (Core text) (Death of a Naturalist, Door into the Dark, The Haw Lantern) Owen Sheers: Skirrid Hill (Partner text) In some cases, those answering Question 10 (being young) could have paid more attention to the key words in the question - while loss of innocence and childhood are valid aspects of ‘being young’, it is essential that candidates answer the question that has been asked. Candidates explored a range of valid relationships for Question 11, including parent/child, love between men and women and the poets’ relationships with the land. Eavan Boland: Selected Poems (Core text) (New Territory, The War Horse, The Journey) Clare Pollard: Look, Clare! Look! (Partner text) No responses were seen. © WJEC CBAC Ltd. 2 Section B: Drama post-1990 AO1 A significant number of candidates struggled to focus on key words in the questions. It is essential that candidates read the question carefully and answer the question that has been asked. Some candidates worked through the given extract chronologically. This led to a lack of relevance in places. Some candidates are not spending enough time on the given extract. A good rule of thumb is to do approximately 50% of the essay on the given extract. Some candidates did not write about a second extract, or only mentioned another part of the play briefly or in passing. This affected the marks that could be awarded in AO1 and AO4. AO2 As has been noted in previous years, AO2 was often weaker than in Section A (and some candidates are still referring to the play as a ‘novel’ or a ‘book’). In many cases there was not enough direct comment on dramatic techniques. Many candidates were not thinking about how meaning/effects in drama are created by more than words. This is particularly true of some of the responses on Arcadia. It is essential that candidates discuss a range of dramatic techniques including stage directions, props, costume, lighting, sound effects etc. There is a useful teaching aid on the WJEC secure website (under CPD 2011) on how to approach and revise AO2 for Section B. The task is based on Arcadia, but there is an accompanying handout with notes on how to adapt the task for any of the set plays. AO4 As mentioned in the previous report, some candidates discussed characters as real people rather than as fictional constructs. It can be useful to encourage candidates to use the word ‘presents’ when discussing characters, and to think of the function of the character within the play. There were, however, some good examples of candidates discussing the function of Sylvia in Broken Glass and Irina in Murmuring Judges. It is essential that links to context are specific, relevant to the question and grounded in the text. Candidates who wrote on Miller were especially good on the significance and influence of important contextual influences (for example, how the Depression, antiSemitism, events in Germany, new ideas in psychology etc. had influenced Miller's creation of characters and plot). Some candidates writing on Friel included effective and confident links to Catholicism, paganism and de Valera’s government. However, in some cases, candidates made only limited/general reference to Catholicism. © WJEC CBAC Ltd. 3 Notes on Questions David Hare: Murmuring Judges Many candidates made relevant links between the play and contextual issues, such as the Guildford 4 and Birmingham 6 cases and Hare’s Asking Around. There were some particularly strong responses to Question 14 (sexism). David Mamet: Oleanna A significant number of candidates struggled to focus on key words in Section B and this was particularly true of the Mamet questions. Question 15 (use and misuse of language) produced many responses which wanted to discuss power or miscommunication. These themes overlap with the use and misuse of language but often led to responses which included quite a lot of irrelevance. Question16 (presentation of/attitudes to women) in particular produced a number of responses which struggled to focus on the question; quite a few candidates tended to describe John and Carol's relationship, or offered character studies. Brian Friel: Dancing at Lughnasa There were some strong responses to Question 17 (religion) with some effective contrasts being made between Catholicism and paganism. Very few responses were seen on Question 18 (ceremony and ritual). Tom Stoppard: Arcadia There were some interesting discussions of Stoppard’s use of time shifts for Question 19 (the past). However, some candidates answering on Question 20 (gender) ended up writing character studies of Thomasina and Septimus rather than discussing gender specifically. In addition, some candidates worked their way through the extract chronologically (rather than selecting key techniques to discuss). This meant that not all material was relevant. Arthur Miller: Broken Glass Question 21 (women) was approached most effectively when candidates explored attitudes to women in addition to the presentation of women. Stronger answers focused on the role and function of Harriet and Sylvia, weaker responses tended to include discussion of the characters as if they were real people. Candidates found a number of ways into Question 22 (issues (in 1930s society) including events in Germany, attitudes to women, marriage and sex, anti-Semitism and the effects of the Depression. The strongest answers kept focus on the text rather than being driven by context. Diane Samuels: Kindertransport Candidates answering on Question 23 (mothers/mother figures) made useful links between the different mother/child relationships presented in the play. There were some strong responses to Question 24 (social/political issues) with candidates discussing a number of issues including anti-Semitism, the Kindertransport and the effects of WWII. © WJEC CBAC Ltd. 4 ENGLISH LITERATURE General Certificate of Education January 2014 Advanced LT4: Poetry and Drama 2 Principal Examiner: Stephen Purcell General Remarks Although there was a very small entry for this paper, there was a variety of texts on show and it was pleasing to see some breadth in responses to the range of opportunities in Section A. Textual knowledge was sometimes quite secure for this relatively early stage of the course and some candidates were able to make close and sustained textual references to support their ideas. If there was a general weakness, it was in the construction of essays where many candidates appeared to lack expertise and confidence. Often, there was a broad-brush approach where raw material was simply laid out for the examiner’s inspection without much attention to the shaping devices which good essays employ in order to maintain focus on the task. At its worst, this approach produced lengthy essays which were poorly organised, repetitive and unfocused. It would benefit candidates enormously to spend time discussing and practising essay strategies such as the use of “signpost” words along with vocabulary designed to echo the central issue in the title. Essay Technique (AO1) Based on observations of a common approach evident at some centres, candidates still appear to be receiving advice to spend time at the start of essays explaining what they are going to do and what materials they will be using. As reports have made clear in the past, this is a poor use of examination time. Candidates’ efforts need to be focused relevantly from the start and their intentions should be immediately apparent from their choice of materials and the ways they explore those materials – an essay “menu” does not contribute usefully to a candidate’s literary responses, but, like all displacement activities, it does distract from the important tasks in hand! As they introduce their essays, candidates would be well advised to get straight to the heart of the task they have been set. The two examples of opening strategies to question 1 below should demonstrate the point clearly. Explore some of the ways poets make use of imagery. 1. “In this essay I am going to write about Blake’s poetry and I will be analysing “London”, “Holy Thursday” and “A Poison Tree” while making comparative reference to “Performance” by Les Murray. William Blake wrote at the time of the industrial revolution when there was a good deal of social deprivation and hardship especially in cities such as London where the poor were forced to labour long hours and had little opportunity for leisure or the freedom to laugh and play which Blake so valued................” (Candidates should be advised to avoid this approach.) 2. “Images of infants crying “’Weep ‘weep” or sleeping in “coffins black” are used potently by Blake to illustrate the way that children become the victims of a callous and deformed society.....” (A much better opening to a literary essay.) © WJEC CBAC Ltd. 5 Candidates should see that the first example offers an unproductive menu followed by an introduction to what appears to be a social history essay. The second places the emphasis squarely upon how Blake has made use of imagery in his writing with economical, supporting quotation. A clear understanding of the differences between these examples would have an enormously positive impact upon the performance of candidates as they tackle literary essays. AO2 Purposeful discussion or perceptive critical analysis and evaluation of poetry are skills which were found wanting in a large proportion of essays. At this level, candidates should be clear that approaching meaning in poetry through formulaic equivalences (e.g. a lamb means innocence; a red rose means sexual love) does not demonstrate creative engagement and will be neither purposeful nor perceptive unless part of a carefully reasoned and supported analysis. In their responses to all poetry – and especially unseen poems – candidates need to be warned of the dangers of literalism on one side (e.g. “The poem ‘Performance’ is about somebody performing”) and unsupportable fantasy (e.g. “Les Murray’s poem shows him at an early, insecure stage of his career, reading his work to an audience as part of a festival.”). In order to meet the higher band criteria for AO2, candidates must explore directly the language, form and structure of poems on the understanding that ambiguity is at the heart of poetic meaning and comments need to be provisional rather than assertions of “fact” or certainty. AO3i Candidates need to be reminded that marks are awarded under this strand of AO3 for connections between texts. There were many examples of candidates writing about the core and partner texts in parallel which, of course, does not really establish connections between them. This is a matter of essay technique which needs practice. AO3ii There was evidence of carefully learned critical views being indiscriminately sprinkled throughout essays without consideration of relevance or appropriateness. A glance at the assessment grid will show that no matter how many views are quoted, if they are not linked relevantly to the candidate’s argument, rewards cannot go beyond Bands 1 or 2 because we cannot say that a candidate “makes use” of other interpretations (Band 3) until those views are applied relevantly. There are clear signs that candidates need careful guidance on how to use critical views effectively. AO4 In order to be able to use contextual materials perceptively, candidates must be able to appreciate the difference between the following 2 statements written in response to “Explore some of the ways poets make use of imagery.” 1. “In ‘Batter my heart three-personed God” Donne asks God to “break, blow, burn and make me new.” This is a reference to the way protestants were burning catholics in the reign of James 1...............” (An assertive, limiting response which is neither sound nor perceptive.) 2. “In Batter my heart three-personed God” Donne asks God to “break, blow, burn, and make me new”, summoning-up violent images of purgatorial fires which might have had a particularly strong resonance in an age when torture and burnings were administered in the name of religion.” (Much better, a perceptive and confident approach which properly connects text and context.) The first example features a comment which it is impossible for candidates to support or verify. It does not indicate a creative or critical engagement with the poetry especially (as was often the case this year) if it is followed by a detailed account of the violent deaths in Donne’s Catholic family. The historical/biographical facts might be accurate, but there is no textual evidence to support so specific and formulaic a connection. There has never been (and will never be) a question requiring candidates to give a close account of Donne’s (or © WJEC CBAC Ltd. 6 any other poet’s) life. Writing of the sort seen in example 1 will harm rather than enhance a literary essay because it tends to substitute broad, historical narrative for literary critical writing about poetry. No doubt, candidates who learned enormous amounts about poets’ lives and wrote lengthily about them will feel that they were productive in the exam and will be disappointed with relatively low marks if they did not leave themselves time to analyse the poetry itself in a relevant and supported way. The second example of the use of context is a brief, valid, well-integrated point which fits comfortably into a literary analysis. This successful essay goes on to discuss the literary qualities of Donne’s writing in light of the set task and carefully avoids extended and assertive writing on 17th century religious conflict, or offering textually unsupported assertions about the correspondences between Donne’s poems and specific events in his life. Taken together, the issues raised under AO3(ii) and AO4 above point to a tendency of candidates to strive for rewards for “facts” they have learned and remembered rather than for the skills of writing an interpretive and aptly supported literary essay. Section A: Critical Reading of Poetry There were examples of responses to all 5 of the unseen poems. While there were some thoughtful and interesting interpretations, there were also many examples of superficial readings or misinterpretations. Colleagues might like to look again at this collection of poetry with their classes: in this selection (and arguably with all poetry!) it is particularly important to read attentively until the very last words of each of the poems. In all cases on this paper, it is the final line or two which shapes the meaning of the whole poem. Candidates who did not take sufficient time to read, reflect and plan often fell back on literal readings which did not connect successfully with their core poets. Section B: Shakespeare and Related Drama Most of the observations above apply equally to the questions on drama. From the point of view of essay technique, it is worth adding that candidates need to be clearer about the differences between narrative/descriptive approaches and critical discussions which refer to characters and events in order to contextualise their remarks. For instance: (Responses to Question 8) “Questions about Hamlet’s sanity are a distraction; mad or sane he is the same tragic hero.” Consider Shakespeare’s presentation of Hamlet’s “madness” in the light of this remark and show how your reading of The Revenger’s Tragedy has influenced your ideas. 1. “Hamlet goes to meet the ghost with Horatio and after Hamlet has spoken to his dead father he becomes very agitated telling Horatio and the others that they must keep his secret and they should not think of questioning him further.” [This is descriptive/ narrative writing with only a faint, tangential relevance to Question 8 in the mention of Hamlet becoming “very agitated”.] 2. “Hamlet’s “wild and whirling words” to Horatio after meeting the ghost come soon after we have seen the brooding prince (on whom “the clouds still hang”) rejecting the attentions of the King and Queen. The audience would be justified in doubting Hamlet’s mental health even at this early stage........” [Much better. This is creatively engaged writing which is driven by the task and text.] Similar examples of good and bad practice could be found in responses to all of the plays and, as they practise essay technique, candidates would benefit from matching their own writing against this example and against the performance grid for Section B. GCE English Literature Report January 2014 19/2/14 © WJEC CBAC Ltd. 7 WJEC 245 Western Avenue Cardiff CF5 2YX Tel No 029 2026 5000 Fax 029 2057 5994 E-mail: exams@wjec.co.uk website: www.wjec.co.uk © WJEC CBAC Ltd.