EDI and EFT Security Using Cryptography: Part 1

advertisement

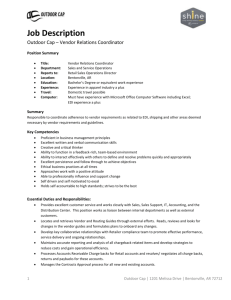

87-01-85 EDI and EFT Security Using Cryptography: Part 1 Previous screen Addison Fischer Payoff A business would not immediately fill a purchase order that arrives in the mail without letterhead or signatures. Yet that is what happens every day in businesses using electronic data interchange. The fraud that has resulted from such laxity has led to calls for improved security for these transactions. This article, the first in a two-part series, examines the security issues involved in electronic data interchange and electronic funds transfers and introduces the types of controls commonly used to secure these transactions. Part 2 will provide a detailed review of cryptographic solutions that not only address these security exposures, but also provide new capabilities at reduced cost. Introduction Electronic data interchange (EDI) and Electronic Funds Transfer processes are integrated components of automated business systems. As electronic business practices extend to every sector of industry (often over unsecured networks), the threats to such transactions increase. This article, the first in a two-part series, presents a functional and technical overview of Electronic Document Interchange and electronic funds transfer (EFT) technologies, standards governing EDI, and security controls. Part 2in this series will focus on the use of cryptographic controls to secure these transactions. Overview of EDI and EFT Systems EDI is a rapidly emerging technology that allows automated commercial transactions to be conducted within organizations and among enterprises. Using Electronic Document Interchange, a business document can be created as an electronic file in the sender's system, sent via any of several possible transmission modes, and processed directly by the recipient's computer. Little or no human intervention is required. EDI documents include, but are certainly not limited to, purchase orders, invoices, letters of credit, tariff filings, tax returns, bills of lading, insurance claims, financial reports, and requests for quotations. Organizations transacting business are known as trading partners. Certain industries have well-developed EDI systems in place. They include retailing, apparel, textile and transportation industries. The health care industry is just beginning to implement EDI widely. Nearly every serious proposal for health care reform includes EDI as an integral component. The standardization of EDI is continuing as many existing industry standards are being incorporated in national and international standards. Among the potential benefits of this technology are considerable cost savings, information accuracy, and improved timeliness. EFT, a subset of EDI, is well-developed and tested. The use of Electronic Funds Transfer by the federal government is substantial. The social security checks of more than 22 million Social Security recipients are deposited electronically. Nearly half of federal salaries are now paid by electronic funds transfer (EFT). Most banks and savings and loans now offer electronic payment of mortgages, loans, and recurring bills. Automated teller machines, electronic deposit, and the rapid clearing of checks among banks are but the most visible benefits ofelectronic funds transfer (EFT) to the consumer. The use of electronic funds transfer (EFT) at point of sale with debit cards is increasing rapidly with online debit networks introduced by VISA, Mastercard, and the Cash Station. Two-thirds of the nation's grocery stores now accept debit cards. Electronic Funds Previous screen Transfer networks are now international in scope, allowing consumers to obtain cash worldwide and banks to transfer funds globally. Security concerns are of paramount importance to the financial industry. electronic funds transfer (EFT) systems have therefore made extensive and very effective use of cryptography to safeguard financial transactions. Advantages of EDI The advantages of EDI are considerable. It can reduce the storm of paper flowing between trading partners, eliminate data reentry errors, speed document filing, and reduce document storage costs. Kmart and Wal-Mart mandated in 1990 that all their trading partners use EDI to conduct business. All suppliers to Target Stores, Inc. use EDI. The use of EDI to reduce inventories and shorten supplier cycle times is critical to modern manufacturing using the just- in-time strategy. This is but one reason General Motors has mandated the use of Electronic Document Interchange by all its suppliers, as have most automotive manufacturers. Similarly, modern grocery retailing is tying its point-of-sale scanners to its inventory management by using the quick response strategy. Inventory records reflect each sale across the checkout scanners, and supplies can be reordered without human intervention at selected threshold levels. The grocery industry's enthusiasm forEDI has expanded beyond quick response as the reception of efficient consumer response strategies demonstrate. These strategies use EDI to confront a host of management issues, including product assortment, product promotion, and space allocation. EDI works synergistically with such inventory and management strategies; without EDI, they would require cumbersome and comparatively slow manual systems. Ideally, human intervention should be needed only when a given EDI transaction creates an unanticipated condition. By eliminating or considerably reducing human intervention, EDI can more than just trim transaction costs. The financial industry cost estimates for each electronic funds transfer (EFT) transaction range from 3c to 6c, onesixth to one-twelfth of the same transaction made by check. The Office of Management and Budget figures that federal transactions made through Electronic Document Interchange cost six cents, but those made by check cost 36 cents. New EDI network services will soon allow corporations to electronically file most types of state tax forms. Electronic Data Systems Corp TaxNet will be operated by the TaxNet Governmental Communications Corp., a division of the Federal of Tax Administrators. National Data Corp. operates the Electronic Tax Filing Service. Both services allow rapid electronic filing, payment, and notification of the receipt of a return. States may mandate such filings if they replicate the cost savings demonstrated by EDI in business. The advantages of EDI for such highly competitive businesses as trucking and the airlines can be considerable. In mature EDI markets, for example, the retailing, apparel, and textile industries, the implementation of EDI is truly a matter of corporate survival, not just competitive advantage. The same may be aid of firms wishing to do business with the US government or in global markets. Components The following sections discuss the functional components of any EDI system. EDI Software. EDI software generally contains a translation component that maps data from the user's (i.e., originator's) application (i.e., record formats) to the Electronic Document Interchange standard message formats. The translation of messages in standard EDI Previous screen formats to the recipient's application is performed by the recipient's EDI software. The communications component adds items to the message to form a complete interchange and interfaces to the underlying communications mechanism. This mechanism can be a lowlevel protocol, such as bisync, or a full-blown messaging protocol, such as X.400. Communications might flow directly to the recipient (i.e, point-to-point) or by means of a third party. There may also be components that handle report writing, management, audit, and printing functions. Nearly all existing EDI implementations, unlike those for electronic funds transfer (EFT), do not currently use cryptography for security. However, a substantial number of Electronic Document Interchange products offering encryption and digital signatures will filter into the market soon. An EDI interchange consists of the production, transmission, receipt of, and response to a formatted text message. Originator and recipient IDs and associated information, as well as one or more functional groups of business data, constitute a message. A functional group consists of one or more related transaction sets, each representing a common business document. For example, transaction set 813 is a tax return; 832 is a price or sales catalog. The transaction sets are usually composed of multiple data segments that provide such information as names, addresses, rates, and handling instruction in a specified sequence. Each data segment is uniquely designated by two or three letter identifiers. Network Systems. Once prepared, an EDI document must be delivered to the trading partner. Data can be sent via high-speed data lines or lower speed dial-up lines, by magnetic tape or diskette, or on X.25 public switched data networks. The documents may be delivered directly, or more typically, by a third-party, value-added network (VAN) or clearinghouse—an EDI postal system. The use of a VAN simplifies the communications process substantially, because communications must be coordinated with one party rather than with all trading partners. The VAN can convert protocols and line speeds, enabling communication between otherwise incompatible systems. Some VANs also offer format translation, electronic forms, fax services, message switching, and access to a variety of data bases. Typical VANs presently provide only a few useful security capabilities. Passwords or authorization codes are required to send or receive documents from electronic mailboxes. A VAN also tracks the movement of documents within its domain and can provide notification of delivery and an audit trail when required. The EDI document originator logs on to the network by using a password. The uploaded document is placed in the recipient's electronic mailbox. The recipient, after meeting network security tests, retrieves mail periodically. Some VANs specialize in particular vertical markets; others are generalists. Examples include Advantis, EDI*Net, EDI*EXPRESS, and AT EasyLink. VANs typically support all public and industry specific standards. Trading Partner Agreements and Third-Party Service Provider Agreements Trading partner agreements (TPAs) or interchange agreements are contractual agreements between two entities that conduct business electronically. They structure the electronic relationship between trading partners, dealing with standards, liability, responsibility, and fees. They are essential to reduce misunderstanding and act as the basis for enforcing future Electronic Document Interchange transactions. The use of Trading Partner Agreement is increasing between EDI users as various model agreements become available and EDI case law develops. Previous screen TPAs can and should explicitly define the security obligations of the two parties, because the EDI system's trustworthiness and reliability are inextricably tied to these obligations. The agreement should cover verification of message delivery, access control, use of cryptographic algorithms, use of digital signatures, notification, and remedial actions in the event of security breaches. Model agreements can, over time, establish common trade practice. As case law develops around them, many trading partners find common provisions are considered to apply to their transactions without their explicit consent. Third-party service provider agreements are similar in concept toTPAs but are contractual agreements between trading partners and VANs or other providers of communications services. The areas that third-party agreements should address include, but are not limited to, access to audit data, data storage periods, and the full range of access control and security procedures. EDI Standards Standards are an essential consideration for the successful implementation of almost any Electronic Document Interchange or Electronic Funds Transfer system. Adherence to standards ensures a uniform level of information protection and suitability for a given task. They are also critical to interoperability and compatibility—factors that are important in software specifically designed to connect a variety of disparate systems. EDI standards establish the format and content for electronic business transactions. International Standards Several international standards are relevant to EDI and Electronic Funds Transfer but the predominant standard is EDIFACT (EDI for Administration Commerce and Trade). The EDIFACT standard is synonymous with the International Standards Organization standard 9735 and was developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Unlike the U.S. standards developed from the bottom up, EDIFACT is a top-down standard. Its creation was a proactive attempt to keep the proliferation of European national standards from becoming an impediment to open trade. EDIFACT is the most popular EDI standard for international electronic business and is likely to be the universal standard after 1997. EDIFACT is not nearly as developed as the principal US EDI standard, but this disparity will probably disappear by 1997 as this international standard becomes aligned with the predominant US standard. An early EDIFACT proponent in the US was the Customs Service, an avid supporter of a global customs system. Other international standards include theTelecommunications Standardization Sector of the International Telecommunications Union's (ITU-TSS), EDI messaging system, X.435, and United Nations Trade Data Interchange, which is principally used in the United Kingdom and likely to be replaced by EDIFACT. The International Telecommunications Union-TSS has standardized a means to convey EDI transactions(both the US X12 and the international EDIFACT) over a reliable message handling system (MHS). This standard, X.435, defines an EDI message type and the services for use in an X.400 MHS.X.400 is the global Message Handling Service standard and provides the following functions that are important to an EDI environment: · Delivery and nondelivery reports. · Message storage capabilities. · Grade of delivery (i.e., priority). Previous screen · Multipart body (e.g., inclusion of computer drawings with an EDI purchase order). · Delivery control (i.e., restrictions on the types or sizes of messages that may be delivered. · A full set of security services. Many companies use X.400 gateways to link their electronic mail systems to the disparate systems operated by their business partners or value-added networks. It promises inexpensive delivery of EDI transactions by merging them with electronic mail to be sent over anyX.400-compliant network. X.435 provides for a single EDI interchange, along with other types of data (e.g. electronic mail) to be conveyed in a message. It is receiving a great deal of interest from VANs, as well as from government agencies currently implementing EDI. Government interest is driven primarily by the inclusion of X.400 and X.435 in the Government Open Systems Interconnect Profile (GOSIP, version 3). Many EDI software developers and VANs have either incorporated X.435 support into their products or announced their intention to do so. National Standards The American National Standards Institute, founded in 1918, is a privately funded, notfor-profit, membership organization that coordinates the development of US voluntary standards. American national Standards Institute (ANSI) is also the principal US member of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the leading International Standards Organization. American national Standards Institute (ANSI) does not develop standards, and it approves them only when it has considerable evidence that those who will be affected by the standards have reached consensus on their provisions. In 1979, American national Standards Institute (ANSI) chartered a new committee, known as Accredited Standards Committee (ASC) X12, to develop EDI standards. In the US, most EDI standards have developed from de facto industry EDI implementations. Many of these specialized industry standards will continue to be used, for example, in the warehousing and transportation industries, but a migration to the more general X12standard is likely to continue. Many industry associations represented on and working with various ASC X12 subcommittees are developing new transaction sets to meet their particular needs. Version 1 of X12 was approved in 1983, followed in 1986 by Version 2. The current version, Version 3, is periodically updated and expanded. X12 standards are properly referred to by a six digit code. The first three digits signify the version number. The fourth and fifth digits stipulate the release number, and the sixth digit represents the subrelease number. These first six digits are typically followed by a six-character industry or trade association identification. The full, twelve-character string is transmitted (in Data Element 480 in the Functional Group Header segment) in all transactions to facilitate coordination and translation. All Trading Partner Agreement involving direct communications should stipulate the version of the standards that are to be used. Partners implementing differing versions cannot be assured of successful data exchanges because X12 releases are neither upwardly nor downwardly compatible. Most EDI software has provisions supporting multiple releases. The use of a VAN to coordinate communications and provide translation also helps with this problem. Often, standards are refined and revised so that disparate standards can be aligned. This is clearly the case with the X12standards. The ASC committee has announced its intention Previous screen of aligning X12 with EDIFACT by 1997 and has established a X12/EDIFACT Alignment Task Group to coordinate future development with a like EDIFACT group. The US government's approach to EDI standards is to follow Federal information Processing Standard (FIPS) 161, which was developed under the auspices of National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Because this standard allows the use of either EDIFACT or X12, the standards alignment should create a unified methodology. Which set of standards to support is an important decision. The most recent release of X12 is a wise choice for domestic users who currently have little need to do business with foreign firms. In the long term, X.435 provides the most comprehensive set of EDI-related open systems standards. Most EDI software is designed to support multiple standards. Periodic revision to X12 or EDIFACT may require the installation of periodic maintenance releases or upgrades to EDI software. Security As both Electronic Document Interchange and Electronic Funds Transfer become more widespread, so does the opportunity for misuse and corruption. With the increasing population of users, progressively more traffic will pass between organizations that have dissimilar backgrounds, security needs, and security controls. The speed with which EDI is being implemented into progressively smaller organizations that were previously little concerned with data security, will leave many users vulnerable. The open system can be interpreted as the conjunction of large networks of computer systems in which computer activity and data flow among the population at large. This understanding encompasses transorganizational computing and views all the world's networks as an aggregated system. This view is appropriate when considering electronic mail, EDI, and electronic commerce in general. Old security paradigms called for a fortress approach in which corporate computing and information resources were structured around a central mainframe, or group of mainframes, concentrated in one or more sites. The goal was to make the site physically secure, to ensure that the networks that accessed the computer were well understood and appropriately secure, to require user validation with passwords, and then to ensure that users could access only programs and data pertinent to their work. In open systems, everyone has a platform. There is no longer a central computer managed by computer security professionals. Even if all users in such organizations manage their own computer security carefully and diligently, all users outside the organization surely will not. Old security paradigms cannot be discarded; they must be augmented. Security for the typical EDI system incorporates security paradigms perfected over the past 30 years and requires new ones as well. Public key cryptography is an essential one. Threats to EDI or electronic funds transfer (EFT) systems include both those from outside the organization and those from within, those made deliberately and those made as the result of error. All can be devastating. Insider threats are estimated to be responsible for from 70% to 80% of the annual dollar loss attributable to all security threats. Much of that loss is attributable to error, accident, and omission; dishonest and disgruntled employees' actions are also responsible for sizable losses. Any security program that focuses exclusively or even principally on threats from the outside is misdirected. Deliberate threats include data destruction by deletion, with viruses or Trojan horses, wiretapping, the creation of bogus documents, and the rerouting or replaying of authorized documents. Accidental threats to an EDI system's security can include data entry errors, deletion of data, misfiling, and the misrouting of documents. Many security threats can be effectively countered by traditional data processing security controls that safeguard entire systems (e.g., optimally scheduled data back-ups and Previous screen secure physical access and password control). Other security threats must rely on innovative technologies, such as public key cryptography, for elegant solutions. In the data communication content security controls are known as security services. The five traditional services are confidentiality, integrity, authentication, nonrepudiation and access control. Any security system for EDI should provide for confidentiality to ensure that sensitive or mission critical information is not disclosed or made available to unauthorized parties. The security of EDI documents must be ensured while they are stored on a computer system or are being transmitted between systems or trading partners. As important as confidentiality is the need to ensure document integrity. This means preventing the accidental or deliberate alteration or destruction of data or even its delay in transit. Authentication may be the most critical of the security concerns. Passwords and personal identification numbers have often been used for keeping unauthorized users from masquerading as legitimate. For high-value transactions, however, these measures are not sufficient, because the systems they run on may be vulnerable to password guessing, data line eavesdropping, and unauthorized disclosure. In the context of electronic business, nonrepudiation is a critical security requirement in two circumstances. If the sender of an electronic order or tax return can later deny responsibility for originating that transmission, the recipient may be potentially injured or the sender may benefit. Similarly, senders and receivers should try to avoid disputes over whether a document was delivered or when delivery took place. Access controls attempt to restrict access to components of the system exclusively to authorized parties. Controls protect hardware, communications media, application software, and data. But access control, long the mainstay of corporate computing security efforts, is insufficient to protect against the roguish acts of authorized parties. One additional capability that would be useful in EDI or electronic funds transfer (EFT) systems is authorization. After ensuring that a particular user signed a transaction, systems should ensure that user's authority to do so. This topic is a new area of interest in American National Standards Institute X9 standards and should eventually find its way into the X12 standards. The intent is to provide additional certification defining what an individual is allowed to do in the way of authorizing resources, such as expenditures, and how this authority is limited. For example, a user might be limited to signing only purchase orders for less than$50,000. Another important limitation would be a stipulation specifying that dual control (e.g., multiple signatures) is required to exercise monetary authority. Such mandated multiple signatures provide the electronic analogue to the tradition of dual controls designed to ensure that individuals cannot act against their organization's policies. Security Controls Organizations using Electronic Document Interchange or Electronic Funds Transfer should implement a variety of security controls. They include security policies and procedures, access control and physical security, and security provisions inTrading Partner Agreement. Security Policies and Procedures An organization's policies and procedures should stress its intent to protect its resources and outline the steps employees must take to provide that protection. These steps should probably include data backup requirements, nondisclosure statements, steps to protect against viruses, procedures for password protection, and requirements to destroy documents in a variety of media. Access Control and Physical Security Previous screen The most basic and obvious security need of an organization may be to control access to its equipment through the use of locks, passwords, and employee identification. Physical access control systems have evolved beyond basic mechanical locks securing one point to microprocessor control systems controlling hundreds of barriers over great distances. Many such systems also monitor fire alarm systems, provide environmental controls, and track employee attendance. Magnetic card and keypad based systems now predominate, with expensive systems relying on biometric criteria reserved for very highsecurity environments. Microcomputer encryption and access control products restrict access to a computer and the data stored within or connected to it. Such advanced products as Fischer International Systems Corp.'s Watchdog provide a host of controls limiting access to both hardware and software and allow these controls to be fine tuned for particular situations. Products should be capable of limiting access to the operating system, diskette and hard drives, parallel and serial ports, and subdirectories and files. An audit trail is a useful security features, as is a password lockout system to deter password guessing. Intrusion detection and reporting capabilities can highlight security weakness in time to avoid catastrophic consequences. Some access control products allow time-based screen blanking and hard disk locking. Recent focus on the shortcomings of traditional password controls have led to the introduction of proactive password checking capabilities that force periodic password replacement and require or generate strong, nontrivial or nonsense passwords. Most logical access control software products for large systems and networks can restrict access based on an employee's classification. Even this basic feature, however, is underused by most organizations. The capability to encrypt the data on disk drives should be considered essential for systems housing financial, medical, or other sensitive data. This is true for companies using Electronic Document Interchange or electronic funds transfer (EFT), as well as for those with computerized payroll, accounting, purchasing, or electronic mail systems. Security on individual platforms, such as a workstation, is addressed by the Department of Defense's Trusted Computer System Evaluation Criteria (TCSEC), also known as the Orange Book. The criteria cover only nonclassified environments and are primarily concerned with identification, authentication, and access control. TheTrusted Computer Security Evaluation Criteria are currently undergoing revision to align them with their Canadian and European equivalents. The revision provides security requirements for various environments. It will more adequately address the needs of the commercial environment, which has been poorly served by the Orange Book. Security Provision in TPAs Security provisions should be integral to most TPAs. The parties should agree to the need for security, the level of security to be provided, and the form that security should take. Different EDI transactions have varying security requirements. Low-value or low-risk transactions have considerably different security needs than do high-value or high-risk ones. A transaction that provides a catalog of products and prices may require only assurance of document integrity, whereas a tax return or medical records require authentication, confidentiality, and integrity assurance. The level of security required and the detail necessary in a TPAs is determined by a risk analysis for the types of transactions occurring between trading partners. Traditional risk analysis tools have a limited value in the present Electronic Document Interchange environment, and until EDI specific tools can be developed, such analysis must be based on limited experience and common sense. Cryptographic Controls Previous screen For more than two decades, the financial industry has mandated the use of symmetric cryptography to safeguard its transactions. The Data Encryption Standard, first authorized for use in 1977, is still in widespread use by numerous industries and has been recertified by the National Institute for Standards and Technology in 1993 for a five-year extension of use. It is unlikely to survive beyond 1998 for use in any but the financial sector. In the EDI environment, cryptographic controls are still in their infancy. They were not deemed necessary when EDI was conducted directly with a minimum number of trusted trading partners. With the new standards and the capability to initiate ad hoc transactions, these cryptographic controls will quickly mature. Conclusion Electronic data interchange is emerging as one of the critical enabling technologies necessary for the rapid development of true global business capability. The spreading use of Electronic Document Interchange leaves many organizations vulnerable to a variety of attacks from both within and outside the organization. Security of the majority of existing Electronic Document Interchange systems is far from ideal. In addition to strengthening proven security safeguards, there is a need to provide new security capabilities. As will be seen in Part 2 of this two-part series, cryptography offers a number of elegant solutions to previously intractable security and legal problems. Author Biographies Addison Fischer Addison Fischer, president and CEO of Fischer International Systems Corporation, is a recognized authority on office automation, workflow technology, and computer security. Fischer is a member of the X12 committee, responsible for developing standards in electronic data interchange. He also serves a member of the X9 committee, involved in formulating US computer security standards.