Nation/Carrington - AP English III Close Readings from The Tempest

advertisement

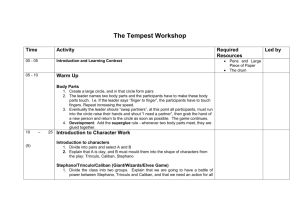

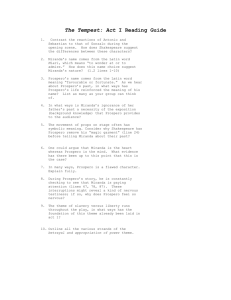

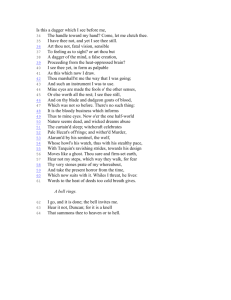

Nation/Carrington - AP English III Close Readings from The Tempest + New World Readings CLOSE READING: PASSAGES FROM THE TEMPEST Instructions: Read the passages as many times as necessary. Use the right side of the table to summarize the content (make sure you understand what the characters are saying) & provide commentary. (If you are using the Word version of the document, you can type directly onto it AND submit it to Turnitin when you are finished). Some things to consider as you read/comment: What is the tone of the characters’ comments? What significant motifs and/or themes are developing? What stylistic choices and patterns do you notice (particular types of figurative or sound devices, recurring images, etc.)? After you have read carefully and understand all of the lines of each scene, answer the specific questions below each passage. From Act I, Scene 2 Something to think about: Though Caliban is sometimes referred to as a “monster” it’s unclear whether he is intended to be a savage/primitive human, or some sort of partially supernatural/non-human being. In any case, he is certainly perceived by Prospero, Miranda, and the other European characters who encounter him as “different” from themselves. From The Tempest PROSPERO Thou poisonous slave, got by the devil himself Upon thy wicked dam, come forth! Enter CALIBAN CALIBAN As wicked dew as e'er my mother brush'd With raven's feather from unwholesome fen Drop on you both! A south-west blow on ye And blister you all o'er! PROSPERO For this, be sure, to-night thou shalt have cramps, Side-stitches that shall pen thy breath up; urchins Shall, for that vast of night that they may work, All exercise on thee; thou shalt be pinch'd As thick as honeycomb, each pinch more stinging Than bees that made 'em. CALIBAN I must eat my dinner. This island's mine, by Sycorax my mother, Which thou takest from me. When thou camest first, Thou strokedst me and madest much of me, wouldst give me Water with berries in't, and teach me how To name the bigger light, and how the less, That burn by day and night: and then I loved thee And show'd thee all the qualities o' the isle, Summary/Commentary The fresh springs, brine-pits, barren place and fertile: Cursed be I that did so! All the charms Of Sycorax, toads, beetles, bats, light on you! For I am all the subjects that you have, Which first was mine own king: and here you sty me In this hard rock, whiles you do keep from me The rest o' the island. PROSPERO Thou most lying slave, Whom stripes may move, not kindness! I have used thee, Filth as thou art, with human care, and lodged thee In mine own cell, till thou didst seek to violate The honour of my child. CALIBAN O ho, O ho! would't had been done! Thou didst prevent me; I had peopled else This isle with Calibans. PROSPERO Abhorred slave, Which any print of goodness wilt not take, Being capable of all ill! I pitied thee, Took pains to make thee speak, taught thee each hour One thing or other: when thou didst not, savage, Know thine own meaning, but wouldst gabble like A thing most brutish, I endow'd thy purposes With words that made them known. But thy vile race, Though thou didst learn, had that in't which good natures Could not abide to be with; therefore wast thou Deservedly confined into this rock, Who hadst deserved more than a prison. CALIBAN You taught me language; and my profit on't Is, I know how to curse. The red plague rid you For learning me your language! PROSPERO Hag-seed, hence! Fetch us in fuel; and be quick, thou'rt best, To answer other business. Shrug'st thou, malice? If thou neglect'st or dost unwillingly What I command, I'll rack thee with old cramps, Fill all thy bones with aches, make thee roar That beasts shall tremble at thy din. CALIBAN No, pray thee. Aside I must obey: his art is of such power, It would control my dam's god, Setebos, and make a vassal of him. PROSPERO So, slave; hence! Exit CALIBAN Specific Questions to Answer for this Passage: 1. How does Prospero feel about Caliban (and why)? 2. How does Caliban feel about Prospero (and why)? 3. Caliban suggests that the island is rightfully his, and that Prospero has stolen it from him. Does Prospero answer these charges at all? If so, what is his justification? If not, why do you think he doesn’t offer a justification? From Act II, Scene 1 From The Tempest GONZALO I' the commonwealth I would by contraries Execute all things; for no kind of traffic Would I admit; no name of magistrate; Letters should not be known; riches, poverty, And use of service, none; contract, succession, Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none; No use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil; No occupation; all men idle, all; And women too, but innocent and pure; No sovereignty;-SEBASTIAN Yet he would be king on't. ANTONIO The latter end of his commonwealth forgets the beginning. GONZALO All things in common nature should produce Summary/Commentary Without sweat or endeavor. Treason, felony, Sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine, Would I not have; but nature should bring forth, Of its own kind, all foison, all abundance, To feed my innocent people. SEBASTIAN No marrying 'mong his subjects? ANTONIO None, man; all idle: whores and knaves. GONZALO I would with such perfection govern, sir, To excel the golden age. Specific Questions to Answer for this Passage: 1. What is the appeal of Gonzalo’s utopia? Why is the island a perfect place to enact it? (Explain). 2. How do Gonzalo, Sebastian, and Antonio’s comments contribute to Shakespeare’s development of their personalities? Explain. 3. Other than adding to the development of their characters, what purpose do Sebastian and Antonio’s comments serve? What perspective has Shakespeare added to the conversation? From Act II, Scene 2 From The Tempest CALIBAN Hast thou not dropp'd from heaven? STEPHANO Out o' the moon, I do assure thee: I was the man i' the moon when time was. CALIBAN I have seen thee in her and I do adore thee: My mistress show'd me thee and thy dog and thy bush. STEPHANO Come, swear to that; kiss the book: I will furnish it anon with new contents; swear. TRINCULO By this good light, this is a very shallow monster! Summary/Commentary I’m afeard of him! A very weak monster! The man i' the moon! A most poor credulous monster! Well drawn, monster, in good sooth! CALIBAN I'll show thee every fertile inch o' th' island; And I will kiss thy foot: I prithee, be my god. TRINCULO By this light, a most perfidious and drunken monster! When 's god's asleep, he'll rob his bottle. CALIBAN I'll kiss thy foot; I'll swear myself thy subject. STEPHANO Come on then; down, and swear. TRINCULO I shall laugh myself to death at this puppy-headed monster. A most scurvy monster! I could find in my heart to beat him,-STEPHANO Come, kiss. TRINCULO But that the poor monster's in drink: an abominable monster! CALIBAN I'll show thee the best springs; I'll pluck thee berries; I'll fish for thee and get thee wood enough. A plague upon the tyrant that I serve! I'll bear him no more sticks, but follow thee, Thou wondrous man. TRINCULO A most ridiculous monster, to make a wonder of a Poor drunkard! CALIBAN I prithee, let me bring thee where crabs grow; And I with my long nails will dig thee pignuts; Show thee a jay's nest and instruct thee how To snare the nimble marmoset; I'll bring thee To clustering filberts and sometimes I'll get thee Young scamels from the rock. Wilt thou go with me? STEPHANO I prithee now, lead the way without any more talking. Trinculo, the king and all our company else being drowned, we will inherit here. Here; bear my bottle: fellow Trinculo, we'll fill him by and by again. CALIBAN [Sings drunkenly] Farewell master; farewell, farewell! TRINCULO A howling monster: a drunken monster! CALIBAN No more dams I'll make for fish Nor fetch in firing At requiring; Nor scrape trencher, nor wash dish 'Ban, 'Ban, Cacaliban Has a new master: get a new man. Freedom, hey-day! Hey-day, freedom! Freedom, hey-day, freedom! STEPHANO O brave monster! Lead the way. Exeunt Specific Questions to Answer for this Passage: 1. What attitude(s) toward Caliban does Trinculo reveal in his asides? What is the effect of the repetition of the term “monster” and its combination with words like “poor,” “puppy-headed,” or “ridiculous”? 2. What will be the nature of Caliban’s relationship with Stephano and Trinculo? What does he have to offer them? What can they offer him? Is this a mutually beneficial relationship or more one-sided? 3. What elements of Caliban’s speech make his language more beautiful and poetic than that of Trinculo and Stefano? Why might Shakespeare write the dialogue this way? From Act III, Scene 2 From The Tempest CALIBAN I thank my noble lord. Wilt thou be pleased to hearken once again to the suit I made to thee? Summary/Commentary STEPHANO Marry, kneel and repeat it; I will stand, and so shall Trinculo. CALIBAN As I told thee before, I am subject to a tyrant, a sorcerer, that by his cunning hath cheated me of the island. … I say, by sorcery he got this isle; From me he got it. If thy greatness will Revenge it on him,--for I know thou darest, But this thing dare not,-STEPHANO That's most certain. CALIBAN Thou shalt be lord of it and I'll serve thee. STEPHANO How now shall this be compassed? Canst thou bring me to the party? CALIBAN Yea, yea, my lord: I'll yield him thee asleep, Where thou mayst knock a nail into his head. … Why, as I told thee, 'tis a custom with him, I' th' afternoon to sleep: there thou mayst brain him, Having first seized his books, or with a log Batter his skull, or paunch him with a stake, Or cut his wezand with thy knife. Remember First to possess his books; for without them He's but a sot, as I am, nor hath not One spirit to command: they all do hate him As rootedly as I. Burn but his books. He has brave utensils,--for so he calls them-Which when he has a house, he'll deck withal. And that most deeply to consider is The beauty of his daughter; he himself Calls her a nonpareil: I never saw a woman, But only Sycorax my dam and she; But she as far surpasseth Sycorax As great'st does least. STEPHANO Is it so brave a lass? CALIBAN Ay, lord; she will become thy bed, I warrant. And bring thee forth brave brood. STEPHANO Monster, I will kill this man: his daughter and I will be king and queen--save our graces!--and Trinculo and thyself shall be viceroys. Dost thou like the plot, Trinculo? TRINCULO Excellent. … CALIBAN Within this half hour will he be asleep: Wilt thou destroy him then? STEPHANO Ay, on mine honour. CALIBAN [to Stephano and Trinculo, who are frightened when an invisible spirit who’s been spying on them plays a tune on his “tabour and pipe” – sort of like a drum and flute] Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises, Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not. Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments Will hum about mine ears, and sometime voices That, if I then had waked after long sleep, Will make me sleep again: and then, in dreaming, The clouds methought would open and show riches Ready to drop upon me that, when I waked, I cried to dream again. STEPHANO This will prove a brave kingdom to me, where I shall have my music for nothing. CALIBAN When Prospero is destroyed. Specific Questions to Answer for this Passage: 1. What possibilities does the island represent for Stephano and Trinculo? 2. What is its value and importance to Caliban? In what way(s) do his lines beginning with “be not afeard” reveal his feelings about the island? Again, in what ways does Shakespeare make his language more lovely, poetic than Trinculo’s or Stefano’s? 3. What kinds of power does each character hold? Which character do you take the most seriously and why? 4. What does the scene suggest about the characters’ attitudes towards women? What is the value and importance of women to these men? From Act V, Scene 1 From The Tempest Summary/Commentary MIRANDA O, wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, That has such people in't! PROSPERO 'Tis new to thee. Specific Question to Answer for this Passage: 1. The phrase “new world” was often used during Shakespeare’s time to describe lands such as the Caribbean, and North and South America, then just beginning to be explored by Europeans. What emotional/imaginative connotations does the phrase carry with it? What significance might modern readers find in Prospero’s comment? NEW WORLD READINGS-TO ACCOMPANY THE TEMPEST Introduction Since the mid-twentieth century, most scholars approach The Tempest at least partially through a “post-colonial” lens. This interpretation of the play focuses on the island as a metaphor for the “new world” and on Ariel and Caliban as symbolic representatives of people (such as Africans or Native Americans) disenfranchised by European colonizers. It’s easy to see how readers might draw these sorts of connections – especially since England and other European countries were actively engaged in colonizing Africa and the Americas at the time the play was written. The question is: what is Shakespeare’s intent? There are a few possibilities. Perhaps he is celebrating (maybe even romanticizing or glamorizing) the excitement and adventure of a “brave new world.” Or maybe he is exploring some of the thorny moral issues of the imperial/colonial system—raising questions about and even critiquing the ethics of exploration and colonization. What do you think? Related Texts The following texts offer additional perspectives on the issues/themes explored in The Tempest. There are a total of 9 texts provided – they are labeled as sources A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and I. Read and provide commentary on each text. (A commentary box is provided at the conclusion of each text. If you’re using the Word file, you can type directly onto the document AND submit it to Turnitin when you are finished.) In your reading/comments, be sure to give special consideration to the following: Each speaker’s tone/point of view (particularly when what is said may not be exactly the same as what is meant); Any questions posed in the introductory material provided with each passage. **Please be aware that the essay portion of the summer assignment will require you to not only cite specific evidence from The Tempest, but also from the following source material. Source A: Native American Origin Stories From Corn Mother (Penobscot Indian Origin Story) and from “The Earth on Turtle’s Back” (Onondaga-Northeast Woodlands creation narrative, retold by Michael Caduto and Joseph Bruchac) The Penobscot people are indigenous to what is now northeastern New England, particularly Maine. They are a part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, a group of cultures in the Algonquin family. The excerpt below comes from their origin story, in which First Mother ultimately sacrifices her life in order to feed her children (her body becoming corn – a staple food of many eastern tribes). The Onondaga are one of the original five nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, a collection of tribal cultures living in and around the Great Lakes region. Their creation narrative tells of a time before the earth was created, when there was only sky and water. It begins with the story of the Skyland chief, whose young, pregnant wife falls through a whole and plummets to earth. The sea birds and animals see her falling, and she is caught by two swans. The animals realize that the woman cannot live in the water, and determine to help create a place for her. Each story reveals some culturally significant attitudes about nature, power, and the individual’s relationship to the community. Based on these narratives, what inferences might you draw about Penobscot and Onondaga culture and values? How do those values compare with the European attitudes suggested by the other sources in this exercise? How do the values compare with Shakespeare’s treatment of similar themes in The Tempest? How do the Penobscot and Onondaga people’s representation of themselves compare with Shakespeare’s representation of an indigenous person (Caliban) in The Tempest? From Corn Mother: When Koskurbeh, the All-maker, lived on earth, there were no people yet. But one day when the sun was high, a youth appeared and called him, “Uncle, brother of my mother.” This young man was born from the foam of the waves, foam quickened by the wind and warmed by the sun. It was the motion of the wind, the moistness of the water and the sun’s warmth which gave him life—warmth above all, because warmth is life. And the young man lived with Koskurbeh and became his chief helper. Now, after these two powerful beings had created all manner of things, there came to them, as the sun was shining at high noon, a beautiful girl. She was born of the wonderful earth plant, and of the dew, and of warmth. Because a drop of dew fell on a leaf and was warmed by the sun, and the warming sun is life, this girl came into being – from a green living plant, from moisture, and from warmth. … The youth, the Great Nephew, married her, and the girl conceived and thus became First Mother. … Now the people increased and became numerous. They lived by hunting, and the more people there were, the less game they found. They were hunting it out, and as the animals decreased, starvation came upon the people. And First Mother pitied them. … Her husband asked: “How can I make you smile? How can I make you happy?” “There is only one thing that will stop my tears.” “What is it?” asked her husband. “It is this: you must kill me.” … First Mother said: “Tomorrow at high noon you must do it. After you have killed me, let two of our sons take hold of my hair and drag my body over that empty patch of earth. Let them drag me back and forth, back and forth, over every part of the patch, until all my flesh has been torn from my body. Afterwards, take my bones, gather them up, and bury them in the middle of this clearing. Then leave that place.” She smiled and said, “Wait seven moons and then come back, and you will find my flesh there, flesh given out of love, and it will nourish and strengthen you forever and ever.” So it was done. … When the husband and his children and his children’s children came back to that place after seven moons had passed, they found the earth covered with tall, green, tasseled plants. The plants fruit—corn—was First Mother’s flesh, given so that the people might live and flourish. … Following her instructions, they did not eat all, but put many kernels back into the earth. In this way, her flesh and spirit renewed themselves every seven months, generation after generation. From “The Earth on Turtle’s Back”: So the birds and animals decided that someone would have to bring up Earth. One by one they tried. The Duck dove down first, some say. He swam down and down, far beneath the surface, but could not reach the bottom and floated back up. Then the Beaver tried. He went even deeper, so deep that it was all dark, but he could not reach the bottom, either. The Loon tried, swimming with his strong wings. He was gone a long, long time, but he, too, failed to bring up Earth. Soon it seemed that all had tried and all had failed. Then a small voice spoke up. “I will bring up Earth or die trying.” They looked to see who it was. It was the tiny Muskrat. She dove down and swam and swam. She was not as strong or as swift as the others, but she was determined. She went so deep that it was all dark, and still she swam deeper. She went so deep that her lungs felt ready to burst, but she swam deeper still. At last, just as she was becoming unconscious, she reached out one small paw and grasped at the bottom, barely touching it before she floated up, almost dead. When the other animals saw her break the surface they thought she had failed. Then they saw her right paw was held tightly shut. “She has the Earth,” they said. “Now where can we put it?” “Place it on my back,” said a deep voice. It was the Great Turtle, who had come up from the depths. They brought the Muskrat over to the Great Turtle and placed her paw against his back. To this day there are marks at the back of the Turtle’s shell which were made by Muskrat’s paw. The tiny bit of Earth fell on the back of the turtle. Almost immediately, it began to grow larger and larger and larger until it became the whole world. Then the two Swans brought the Sky Woman down. She stepped onto the new Earth and opened her hand, letting the seeds fall onto the bare soil. From those seeds the trees and grass sprang up. Life on Earth had begun. Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed): Source B: From Journal of the First Voyage to America Christopher Columbus Columbus is remembered as the first European to reach the “new world” (although it now seems likely that others actually reached it earlier). The text below references events that occurred in October, 1492 – nine days after Columbus’s landing in what is now San Salvador in the Bahamas. The account was written for King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, who had financed Columbus’s expedition. By Shakespeare’s time, Columbus—along with his travels and discoveries—would have been well-known to most Europeans. Take close note of the tone and content of the excerpt below. What vision of the “new world” does Columbus paint for his readers? What cultural attitudes does he reveal concerning exploration, discovery, land, nature, the island’s native inhabitants, and the concept of ownership? Where/how do we see these attitudes echoed (and/or contradicted) in The Tempest? Everything looked as green as in April in Andalusia. The melody of the birds was so exquisite that one was never willing to part from the sound, and the flocks of parrots obscured the heavens. The diversity in the appearance of the feathered tribe from those of our country is extremely curious. A thousand different sorts of trees, with their fruit were to be met with, and of a wonderfully delicious odor. It was a great affliction to me to be ignorant of their natures, for I am very certain they are all valuable; specimens of them and of the plants I have preserved. Going around one of these lakes, I saw a snake, which we killed, and I have kept the skin for your Highnesses; upon being discovered he took to the water, whither we followed him, as it was not deep, and dispatched him with our lances; he was seven spans in length; I think there are many more such about here. I discovered also the aloe tree, and am determined to take on board the ship tomorrow, ten quintals of it, as I am told it is valuable. While we were in search of good water, we came upon a village of the natives about half a league from the place where the ships lay; the inhabitants on discovering us abandoned their houses, and took to flight, carrying off their goods to the mountain. I ordered that nothing which they had left should be taken, not even the value of a pin. Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed): Source C: From “Of the Cannibals” Michel de Montaigne (translated by Paul Brians) Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) was a French courtier and author of Essais, the extensive collection of philosophical writings that was instrumental in establishing the essay as a literary form. His essay “Of the Cannibals,” excerpts of which appear below, appeared in 1603 in an English translation by John Florio – a translation that Shakespeare is believed to have read. Montaigne’s argument is that the natural state in which cannibals live is superior in virtue and innocence to the condition of civilization. Where/how do we see that idea echoed in The Tempest? Where/how do we see it contradicted? . . . I do not find that there is anything barbaric or savage about [the natives of the “new world”], according to what I've been told, unless we are to call barbarism whatever differs from our own customs. Indeed, we seem to have no other standard of truth and reason than the opinions and customs of our own country. There at home is always the perfect religion, the perfect legal system--the perfect and most accomplished way of doing everything. These people are wild in the same sense that fruits are, produced by nature, alone, in her ordinary way. Indeed, in that land, it is we who refuse to alter our artificial ways and reject the common order that ought rather to be called wild, or savage. In them the most natural virtues and abilities are alive and vigorous, whereas we have bastardized them and adopted them solely to our corrupt taste. … This is a people … among whom there is no commerce at all, no knowledge of letters, no knowledge of numbers, nor any judges, or political superiority, no habit of service, riches, or poverty, no contracts, no inheritance, no divisions of property, no occupations but easy ones, no respect for any relationship except ordinary family ones, no clothes, no agriculture, no metal, no use of wine or wheat. The very words which mean "lie," "treason," "deception," "greed," "envy," "slander" and "forgiveness" are unknown. … They have their wars against peoples who live beyond their mountains, further inland, to which they go entirely naked, bearing no other arms that bows and sharpened stakes like our hunting spears. The courage with which they fight is amazing: their battles never end except through death of bloodshed, for they do not even understand what fear is. While we quite rightly judge their faults, we are blind to our own. I think it is more barbaric to eat a man alive than to eat him dead, to tear apart through torture and pain a living body which can still feel, or to burn it alive by bits, to let it be gnawed and chewed by dogs or pigs (as we have not only read, but seen, in recent times, not against old enemies but among neighbors and fellow-citizens, and--what is worse--under the pretext of piety and religion.) Better to roast and eat him after he is dead. Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed): Source D: From “True Repertory of the Wracke” William Strachey The Sea Venture was a ship bound for the Jamestown colony that wrecked off the coast of Bermuda in 1609. The passengers survived the shipwreck and found safety on the island, where they made camp for a time before being rescued and heading on to Jamestown. William Strachey (1572 – 1621), a survivor of the wreck, wrote an account of the experience that was almost certainly read by Shakespeare and seems to have provided some of the inspiration for the shipwreck that begins The Tempest. This excerpt from Strachey’s account presents an interesting view of nature. Consider how this view of nature might be reflected in The Tempest. In the play, is nature the opposite of civilization or the harmonious complement to it? What role does land/nature play in both the fascination/appeal of and the sense of danger associated with the “New World”? A dreadful storm and hideous began to blow from out the North-east, which swelling, and roaring as it were by fits, some hours with more violence than others, at length did beat all light from heaven; which like an hell of darkness turned black upon us, so much the more fuller or horror, as in such cases horror and fear use to overrun the troubled, and overmastered senses of all, which (taken up with amazement), the ears lay so sensible to the terrible cries, and murmurs of the winds, and distraction of our company, as who was most armed, and best prepared, was not a little shaken... We were enforced to run her ashore as near the land as we could, which brought us within three-quarters of a mile of shore. ... We found it to be the dangerous and dreaded island, or rather islands of the Bermuda; whereof let me give your Ladyship a brief description before I proceed to my narration. … And hereby also, I hope to deliver the world from a foul and general error: it being counted of most that [the islands of Bermuda] can be no habitation for men, but rather given over to devils and wicked spirits. Whereas indeed we find them now by experience to be as habitable and commodious as most countries of the same climate and situation; insomuch as if the entrance into them were as easy as the place itself is contenting, it had long ere this been inhabited as well as other islands. Thus shall we make it appear that Truth is the daughter of Time, and that men ought not to deny everything which is not subject to their own sense. … Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed): Source E: From The General History of Virginia Captain John Smith Smith’s narrative (which includes the now legendary account of how he was saved by Pocahontas), was published and widely read in England in 1624 – but he recounts events that occurred almost twenty years earlier when he helped to establish the Jamestown colony from 1607-1609. Though he slips out of it occasionally, Smith wrote his narrative in the third person point of view. In the following excerpt, he details some of the work he did to establish the colony and recounts an episode in which he was able to get supplies necessary for the colony’s survival. What attitudes does Smith reveal (directly and/or indirectly) about himself and about the Powhatan Indians? What types of power (if any) does Smith perceive the Indians to have? What types of power does he perceive in himself? How does narrative perspective/point of view contribute to the Smith’s portrayal of both himself and others? What possibilities does the “new world” offer for men like Smith? How does Shakespeare portray these possibilities in The Tempest? The new President, and Martin [original leaders of the expedition], being little beloved, of weak judgment in dangers, and less industry in peace, committed the managing of all things abroad to Captain Smith, who by his own example, good words, and fair promises, set some to mow, others to bind thatch, some to build houses, others to thatch them, himself always bearing the greatest task for his own share, so that in short time, he provided most of them lodgings, neglecting any for himself. This done, seeing the savages' superfluity begin to decrease, (with some of his workmen) [he] shipped himself in the shallop to search the country for trade. The want of the language, knowledge to manage boat without sails, the want of a sufficient power (knowing the multitude of the savages), apparel for his men, and other necessaries, were infinite impediments yet no discouragement. Being but six or seven in company we went down the river to Kecoughtan, where at first they [the Powhatan Indians] scorned him, as a famished man, and would in derision offer him a handful of corn, a piece of bread, for their swords and muskets, and such like proportions also for their apparel. But seeing by trade and courtesy there was nothing to be had, he made bold to try such conclusions as necessity enforced, though contrary to his commission: let fly his muskets, ran his boat on shore, whereat they all fled into the woods. So marching toward their houses, they [Smith and his soldiers] might see great heaps of corn; much ado he had to restrain his hungry soldiers from present taking it, expecting as it happened that the savages would assault them, as not long after they did with most hideous noise. Sixty or seventy of them, some black, some red, some white, some parti-coloured, came in a square order, singing and dancing out of the woods, with their Okee (which was an idol made of skins, stuffed with moss, all painted and hung with chains and copper) borne before them; and in this manner, being well armed with clubs, targets, bows, and arrows, they charged the English, that so kindly received them with their muskets loaded with pistol shot, that down fell their God, and divers lay sprawling on the ground; the rest fled again to the woods, and ere long sent one of their Quiyoughkasoucks to offer peace and redeem their Okee. Smith told them, if only six of them would come unarmed and load his boat, he would not only be their friend but restore them their Okee, and give them beads, copper, and hatchets besides, which on both sides was to their contents performed; and then they brought him venison, turkeys, wild fowl, bread, and what they had singing and dancing in sign of friendship till they departed. Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed): Source F: From “Fear and Love in the Virginia Colony” Adam Goodheart In his 2009 essay, Goodheart discusses the writings and now legendary persona of Captain John Smith, the English explorer so instrumental in the founding of the Jamestown colony in present day Virginia. Smith wrote about his experiences in a number of published works, and Goodheart suggests the possibility of a connection between Smith’s account of the “new world” and the characters and plot of The Tempest. What (if any) aspects of the play support such an interpretation? On a separate (but related) note – based on Goodheart’s summary, what vision of “the new world” does it seem that Smith was painting for his audience? How is this vision echoed (or contradicted) in The Tempest? In 1608, a ship returning from Jamestown had carried with it a letter from Smith to an acquaintance back in the mother country, forty or so pages of close-written foolscap detailing the colonists’ adventures and travails in the New World. Within a few weeks it had been entered for publication as A True Relation of Such Occurrences and Accidents of Noate as Hath Hapned in Virginia Since the First Planting of that Collony, Which is Now Resident in the South Part Thereof, Till the Last Return from Thence. Despite this unwieldy title, the text itself was—by the prose standards of the time—direct, forthright, and vivid, especially in its portraits of some of the characters Smith had met among the Virginia natives. There was Powhatan, the shrewd emperor-priest of the tidewater, presiding in state with chains of pearls around his neck and naked concubines at his feet. There was the chief’s trusted lackey, Rawhunt, “much exceeding in deformitie of person, but of a subtill wit and crafty understanding.” And there was Powhatan’s memorable daughter, “a child of tenne years old, which not only for feature, countenance, and proportion much exceedeth any of the rest of the people, but for wit, and spirit, the only Nonpareil of his Country.” (In the margin of the British Library’s copy next to this passage, a seventeenth-century hand has inserted the word “Pokahontas.”) It is still anyone’s guess whether these descriptions caught the eye of the playwright who would soon invent a romance of a brave new world—the chief inhabitants of which were a shrewd magician-king, his malformed and conniving lackey, and his sprightly daughter. In any case, by the time The Tempest was first performed in 1611, John Smith was at work on another book. … The General Historie of Virginia has enchanted and perplexed its readers for nearly 400 years … To open its pages is, for American readers of the twenty-first century, to be transported into a landscape at once domestic and exotic, familiar and wholly new: a Chesapeake Bay with flocks of green parakeets, shoals of oysters the size of dinner plates, and naked warriors in birchbark canoes—and where, moreover, the fabled passage to India might lurk behind any headland, or mountain of gold around the next bend of any muddy creek … Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed): Source G: From Of Plymouth Plantation William Bradford William Bradford was one of the Puritans (known as “Pilgrims”) who sailed from England to the “new world” on the Mayflower, reaching Plymouth in what is now Massachusetts in 1620. Bradford was a signer of the Mayflower Compact, in which the Pilgrims outlined a system of governance for their colony. He was eventually chosen to be the colony’s second governor. In Of Plymouth Plantation, Bradford recounts the hardships and challenges faced by the Puritans in their new home. As you read, compare the tone of Bradford’s account to what you know of John Smith’s (take note of similarities and differences and consider their significance). Shakespeare—who died in 1616—could not have read Bradford’s text – but are there any connections to be made to the play? In what ways (if any) does The Tempest dramatize some of the same themes, concerns, and/or ideas featured in Bradford’s account of the Puritan settlement? Being thus arrived in a good harbor, and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth, their proper element. … But here I cannot but stay and make a pause, and stand half amazed at this poor people’s present condition…. Being thus passed the vast ocean, and a sea of troubles before them in their preparation … they had now no friends to welcome them nor inns to enteretain or refresh, their weatherbeaten bodies; no houses or much less towns to repair to, to seek for succour. … And for the season it was winter, and they that know the winters of that country know them to be sharp and violent, and subject to cruel and fierce storms, dangerous to travel to known places, much more to searchan unknown coast. Besides, what could they see but a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men— and what multitudes there might be of them they knew not. … Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed): Source H: From “A Model of Christian Charity” John Winthrop John Winthrop—another Puritan—sailed from England to America in 1630 with a charter to form the Massachusetts Bay Colony, of which he became the governor (the earlier founded Plymouth Colony Bradford writes of was eventually incorporated with the Massachusetts Bay Colony). He made his famous sermon either before he and his shipmates sailed from England or while they were in route. Winthrop’s metaphor of the Puritan settlement as the Biblical “city on a hill” has been frequently referenced by American political leaders (maybe most notably President Ronald Reagan) and utilized as trope through which to talk about the American Dream. How does Winthrop’s vision for life in the “new world” correspond with that suggested by Columbus or Smith (or Shakespeare)? Whatsoever we did, or ought to have done, when we lived in England, the same must we do, and more also, where we go. That which the most in their churches maintain as truth in profession only, we must bring into familiar and constant practice; as in this duty of love, we must love brotherly without dissimulation, we must love one another with a pure heart fervently. We must bear one another’s burdens. We must not look only on our own things, but also on the things of our brethren. Neither must we think that the Lord will bear with such failings at our hands as he doth from those among whom we have lived …. Thus stands the cause between God and us. We are entered into covenant with Him for this work. We have taken out a commission. The Lord hath given us leave to draw our own articles. We have professed to enterprise these and those accounts, upon these and those ends. We have hereupon besought Him of favor and blessing. Now if the Lord shall please to hear us, and bring us in peace to the place we desire, then hath He ratified this covenant and sealed our commission, and will expect a strict performance of the articles contained in it; but if we shall neglect the observation of these articles which are the ends we have propounded, and, dissembling with our God, shall fall to embrace this present world and prosecute our carnal intentions, seeking great things for ourselves and our posterity, the Lord will surely break out in wrath against us, and be revenged of such a people, and make us know the price of the breach of such a covenant. Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck, and to provide for our posterity, is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God. For this end, we must be knit together, in this work, as one man. We must entertain each other in brotherly affection. We must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of others’ necessities. We must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekness, gentleness, patience and liberality. We must delight in each other; make others’ conditions our own; rejoice together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, as members of the same body. So shall we keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace. The Lord will be our God, and delight to dwell among us, as His own people, and will command a blessing upon us in all our ways, so that we shall see much more of His wisdom, power, goodness and truth, than formerly we have been acquainted with. We shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies; when He shall make us a praise and glory that men shall say of succeeding plantations, "may the Lord make it like that of New England." For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world. We shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the ways of God, and all professors for God's sake. We shall shame the faces of many of God's worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going. Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed): Source I: From “To Charles Boyle, Earl of Orrery” William Byrd, 1726 William Byrd’s father was a successful merchant/planter on the Virginia frontier, where Byrd himself was born in 1674. Byrd was educated in England, where he became a lawyer and a member of the Royal Society. Byrd cultivated friendships with wealthy and influential members of the British upper class, and when his father died in 1704, Byrd inherited twenty-five thousand acres and a plantation on the James River in Virginia. As a young man, Byrd divided his time between England and the Virginia Colony, returning to his plantation after his marriage to Maria Taylor in 1726. In this letter to his English friend, Byrd discusses his life in the colony – now over 100 years old, but still considered by many to be the “new world.” How has the concept of “American Exceptionalism” developed or evolved in the years since Shakespeare, Smith, Bradford, and Winthrop wrote about the “new world”? Does Byrd’s description of his plantation bear any relationship to Shakespeare’s depiction of the island in The Tempest? Besides the advantages of pure air, we abound in all kinds of provisions without expense (I mean we who have plantations). I have a large family of my own, and my doors are open to everybody, yet I have no bills to pay, and half- acrown will rest undisturbed in my pockets for many moons altogether. Like one of the patriarchs, I have my flock and herds, my bondmen and bondwomen, and every sort of trade amongst my own servants, so that I live in a kind of independence on everyone but Providence. However tho’ this sort of life is without expense yet it is attended with a great deal of trouble. I must take care to keep all my people to their duty, to set all the springs in motion, and to make everyone draw his equal share to carry the machine forward. But then ‘tis an amusement in this silent country, and a continual exercise of our patience and economy. Another thing my Lord, that recommends this country very much—we sit securely under our vines and our fig trees without any danger to our property. … We can rest securely in our beds with all our doors and windows open, and yet find everything exactly in place the next morning. We can travel all over the country, by night and by day, unguarded and unarmed, and never meet with any person so rude as to bid us stand. We have no vagrant mendicants to seize and deafen us wherever we go, as in your island of beggars. Thus my Lord, we are very happy in our Canaan, if we could but forget the onions and fleshpots of Egypt. There are so many temptations in England to inflame the appetite, and charm the senses, that we are content to run all risks to enjoy them. The always had, I must own, too strong an influence upon me, as your Lordship will believe when they could keep me so long from the more solid pleasures of innocence and retirement. Your commentary on this source (expand space as needed):