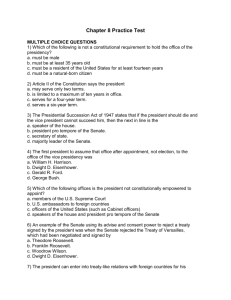

The Fall of the Dominant Presidency: Lawmaking Under Divided

advertisement