Report: Rape and Indecent Assault in Cambodia 2004

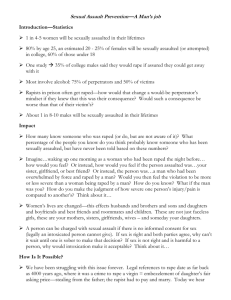

advertisement