“I don't ask for things I don't think I can get.” Regina Giddens as

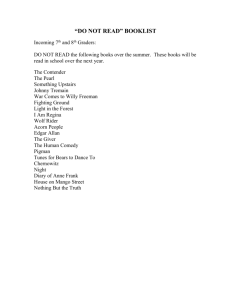

advertisement

“I don't ask for things I don't think I can get.” Regina Giddens as portrayal of a New Southern evil in William Wyler’s “The Little Foxes” (1941) Mónica Ledo Fernández Abstract If moral interpretations are based on the discourse of good, then the concept of evilness, considered as a moral error, must necessarily appear in contrast to the former notion. However, we can yet consider another framework for evil if we focus on the analysis of the villain’s source of wickedness as well as on the effects caused by this evil. According to an ethical and philosophical view, we will question the identity of a famous screen character, Regina Giddens (starring Bette Davis) in William Wyler’s film The Little Foxes (1941), as one of the most malevolent, manipulative, selfish, and evil characters of the 1940s Hollywood cinema. Bette Davis’ role was that of a defiant woman with a greedy and venomous nature. Moved by materialistic desires, Regina becomes an unscrupulous woman capable of any and every moral wrong. Still, she is the absolute protagonist of the film and she even leads the audience to sympathize with her powerful (evil) spirit. By offering a portrayal of Regina Giddens, a new woman in the new South, we will comment on woman’s evilness at a very specific time in the past, the Reconstruction period. But we will also prove that she could very well represent the antecedent of the 21st century’s evil woman, as she can also be compared to some classical villainesses. This study will examine Regina’s behavior, both in a social and a moral context, so as to re-interpret her wickedness as a double-edged sword: a powerful tool in her struggle against tradition as well as the cause for family decay and loss. Key Words: Wickedness, immoral, harm, victim, evildoer, greed, money, power, patriarchy, Reconstruction. ***** There is no period in history when the topic of evil has not been discussed. Although there have been many different points of view and diverse focal points in the study of evil, its definition is still complex and evilness remains difficult to classify as a concept. According to Card’s own definition of evil as presented in her study of evil, Atrocity Paradigm: “I don’t ask for things I don’t think I can get.” Regina Giddens as portrayal of a New Southern evil in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) ___________________________________________________________________________________ 2 _ …an evil is harm that is (1) reasonably foreseeable (or appreciable) and (2) culpably inflicted (or tolerated, aggravated, or maintained), and that (3) deprives, or seriously risks depriving, others of the basics that are necessary to make a life possible and tolerable or decent (or to make a death decent).1 What Card calls “intolerable harm” puts the emphasis on the deed itself, a deed that is insufferable. However, when she talks about “culpable wrongdoing,” she is emphasizing the suffering. Both the deed and the suffering make part of the same evil and we cannot separate them. Therefore, we will consider a framework for evil that explores the perspective of the oppressor’s source of evil as well as the effects caused by this evil. Focusing on Card’s “theory of evil,” we will analyze in this chapter the identity of Regina Giddens as image of evil in William Wyler’s film The Little Foxes (1941). With this purpose, we will pay attention to Regina’s malevolent behavior —both its sources and effects— without leaving aside Regina’s own perspective of the world, so as to understand why she is depicted as one of the most calculating, self-centered, and wicked screen characters of the 1940s. Is this portrayal of evil accurate or must we reconsider Regina’s immoral nature? In order to provide an answer for this question, we will first study vileness in Regina’s character as a social concept: people performing wrong deeds as members of a community, in this case the context of Reconstruction in the South of the United States. On the other hand, we will focus on the analysis of evilness understood as a moral concept: human beings acting maliciously in order to achieve a goal. Evil in this case is inflicted because of the person’s wrong intentions. Both analyses are closely related since moral evil might be born from social evil. As Card claims, “we do not choose evil simply for its own sake.”2 Evil is conceived at a given moment and fed until it grows to be noticeable and later dangerous, even lethal. But there is usually a reason (or several) that lead the perpetrator of evil to commit atrocities. This is what happens to Regina in The Little Foxes; her wickedness doesn’t emerge out of nothing, it comes from two main sources: greed and the desire to achieve power in a world ruled by men. We could define greed as an immoderate desire to possess more than what we need in terms of material wealth. Whereas from a religious point of view it implies the abandonment of the spiritual realm —therefore becoming a sin—, it would be considered as a wrongdoing following Card’s theory. That is to say, greed by itself is morally incorrect, but it is not yet an Mónica Ledo Fernández 3 ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ evil. Even though all the Hubbards in the film (Ben, Oscar, and Regina) are representative of greed, Regina is depicted as especially avaricious. However, despite her rapacious behavior, we might wonder if she’s greedy for money or for something else. And in order to find out, we need to examine the sources of this greed, that is, to go back to Regina’s youth. It is not explicit in the film, but we can learn about Regina’s past in Lillian Hellman’s play Another Part of the Forest (1946) and Michael Gordon’s film (1948) under the same title. The American playwright actually wrote this prequel after the success of The Little Foxes (1939), in which Wyler’s film is based on, but taking into account the events of the past is essential to understand Regina’s attitude in The Little Foxes twenty years later. Set in a fictional town in Alabama in 1880, in Another Part of the Forest we meet the prosperous and avaricious Hubbard family in their rise to prominence. Back then Regina was a sexually active young woman who wanted to live in Chicago with a former Confederate officer she was in love with. However, her father, who showed an unnatural proximity to her, avoided her escape. Later, her elder brother Ben, usurped the patriarch’s power and strongly encouraged Regina to marry Horace Giddens, a wealthy town clerk. After giving up the idea of love, Regina wants to have “everything” else, that is, wealth, independence, and a social life she can enjoy, in a word, power. Twenty years later, she’s still struggling to make her dream come true: Yes, I’m going to live there [in Chicago]. I’m gonna take Alexandra with me. I’ll give big parties and see that she meets the best people and the right young men too. And later on, I’ll take trips to New York and Paris, and have what I want, everything I want. As the economic power belongs to men, Regina needs to plan well her moves if she wants to be successful. Another source for her evil actions is therefore this financial inequality she thinks absurd. As a married woman, she depends now on her husband, and she cannot manage his money at her own will: At century’s end married-women’s-property law in the South —and in the rest of the country, for that matter— was an odd assortment of powers, obligations, and disabilities […] As an index to southern attitudes toward women, the law is completely unreliable.3 Determined to change this situation and very hungry for power, Regina decides to take advantage on her brothers, without caring at all about “I don’t ask for things I don’t think I can get.” Regina Giddens as portrayal of a New Southern evil in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) ___________________________________________________________________________________ 4 _ family bonds. Her sharp and calculating conduct makes Ben and Oscar look ridiculous as Regina’s rivals. Despite having the power and position (within a patriarchal society where men are still the economic supporters), their aptitude and manners are much inferior to those of Regina. They are focused on their aim, but they lack intellect and they look like puppets in her hands. The turn of century is the perfect context to make money in the South. The Reconstruction brings with it a whole new emergent crew of rapacious characters, very different from those mythic gentlemanly figures of the Old South. Carpetbaggers and scalawags* are the main representatives of greed and Regina immediately welcomes money coming from either of these groups. Now that the North is investing in the South, Regina’s selfishness and her desire to be an equal to her brothers increases at the prospect of making capital. There is nothing she wants more than to “spoil the vines,” and she emerges as the major fox of the Hubbard family. When Mr Marshall, a newcomer from the North, comes to establish a cotton mill in the South, the Hubbards do not doubt to take part in his business, and Regina becomes a scalawag herself by allying with her brothers and this man in order to have her own share. Ben and Oscar will make a deal with Mr Marshall, but it is Regina the one who helps them to get it by acting charming and masquerading her brothers’ vicious attitudes idiotically reflected in their talks. Although she is denied to take part in business for being a woman, her brothers depend on her appeal and intelligence. Is she to blame here for trying to charm Mr. Marshall for her own benefit? She’s malicious, yes, she’s manipulative, she’s proud of herself and self-centered but, is she evil? Surrounded by vicious men, she grows selfish and treacherous, manipulating her brothers until she eventually has the opportunity to blackmail them, foreseeing success: REGINA: Perhaps he [Horace] is remaining silent because he doesn’t think he’s getting enough for his money. Seventy five thousand he has to put up, that’s a lot of money. […] OSCAR: He’s only putting up a third of the money. You put up a third, you get a third. What else could he expect, Regina? REGINA: Well, I don’t know. I don’t know about those things. It would seem you put up a third, you get a third. And yet again, there’s no law about it, is there? I should think if your money was badly needed, you must just say “I want more. I want a larger share.” You boys have done that, I’ve heard you say so. BEN: So you believe Horace is deliberately holding out? Well, I Mónica Ledo Fernández 5 ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ don’t. But I do believe that’s what you want. Am I right, Regina? REGINA: Well, I wouldn’t like to persuade Horace unless he gets a larger share. After all, he’s my husband. I must look after his interests. […] OSCAR: You’re talking big tonight. REGINA: Am I? Oscar, you should know me well enough by now to know I don’t ask for things I don’t think I can get. Regina speaks for her husband when in reality she is plotting against him as well. She astutely negotiates her own share by manipulating her brothers. Her vice is latent here and her cunning thought leads her to act immorally. She constantly emphasizes her alleged ignorance for business, ironically in the middle of proving herself as a sharp negotiator. By not asking for things she doesn’t think she can get she may be causing harm to her brothers, but as “harm is not evil unless aggravated, supported, or produced by culpable wrongdoing,”4 we cannot catalogue her as an evil woman yet. The little foxes are growing to become big foxes now, and Regina’s greed helps her to reach enough power to not be left outside. One of the famous quotes of the film points out to the corruption of the Hubbards, and especially to Regina’s distortion: “There’s people that eats up the whole Earth and all the people on it, like in the Bible with the locust.” Regina, despite being a woman in a male’s world, is now even more dangerous than her brothers for a simple reason: she certainly wants “to eat up the whole Earth,” she knows how to, and she is confident she can do it. John Stuart Mill considers that the so-called self-centred vices “are not properly immoralities and to whatever pitch they may be carried, do not constitute wickedness,”5 that is, these vices may be thoughtless but we cannot classify them as immoral. Bearing this in mind, shouldn’t we re-interpret Regina’s evil in a different light? Her deeds, in the end, originate from a clearly self-regarding vice, greed. This is morally wrong, selfish, even egotistical, but not wicked yet. However, as we will see towards the end of the film, these vices are likely to grow more bigger and addictive, deriving into atrociousness at some point. Therefore, even if the source of Regina’s evil was originally an immoral vice, she will eventually become an evildoer and be forever remembered as a depraved woman after letting her husband die. Another of the main sources for Regina’s wickedness appears to be the patriarchal power, which causes a strong reaction of rejection in her. As the economic power still belongs to men, women find themselves dependent “I don’t ask for things I don’t think I can get.” Regina Giddens as portrayal of a New Southern evil in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) ___________________________________________________________________________________ 6 _ on them at the same time they start to be conscious about their possibilities —and their right— to become man’s equals. Barbara Arrighi defines patriarchy as “a system of domination by a few men over all others, including children, women, and men,” and she emphasizes the fact that women are on the bottom “only slightly above children (if that).”6 In Another Part of the Forest we learn that Regina’s mother was a clear example of a submissive woman under her husband’s dominion, but Regina refuses to take her mother as a role model. In fact, she probably finds her so weak and pitiable that she decides to become her opposite. As a result, Regina’s feeling of dislike for her mother’s passivity also contributes to make her actively react against male power, at the same time it clearly becomes one of Regina’s sources of evil. In order to fight tradition, Regina makes herself into a new woman and adapts to modern times by means of evil. The tools she uses against man’s power are blackmail and manipulation, and she doesn’t mind reaching dangerous extremes. In a period of industrial growth, Regina interprets capitalism as a system that provides women with a possibility for empowerment. Like her, other women in the Reconstruction period saw industrialism as their ally, and they started to challenge man’s power emerging as the first feminists. In Gordons’ words, they contributed to “the ‘modernization’ of male domination, its adaptation to new economic and social conditions.”7 Regina Giddens could well come into view as the image of the Southern feminist, but the method she chooses to fight is an immoral and wrong one, and it will keep her away from being interpreted as a real heroine. Regina wonders what will be her own8 and why women and property seem to be irreconcilable opposites. Until Mary Beard work on equity law, nineteenth century women were considered to be “covert” that is, economically covered by the marriage relationships. But with the time, this perspective changed and, as Censer notices, the prohibition of entering the business world for women “was neither complete nor permanent.”9 Moreover, we cannot forget to mention certain opinions that emphasize a feminist aspect in the changes that women’s space was about to suffer, as the following interpretation of Finney: The prominence of female characters in the period had everything to do with the situation of women at the turn of the century, a moment when the first feminist movement was challenging the traditional view that women are fundamentally different from and subordinate to men.10 Mónica Ledo Fernández 7 ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ Patriarchy may submit women in many different contexts (social, political, personal, etc), however, as previously explained, Regina gets involved in a battle against brotherly authority mostly because of money issues. In the film we can see how Ben admires her sister’s intelligence, but he still thinks he has the right to control her, not because of brotherly ties but because he is a (business)-man and he believes he can use her to make profit for himself. For Ben, she is an admirable woman in her cynicism, but still and inferior. Judging from the complicity that Regina and Ben have now for plotting, nobody would say that she is resented with him for having made her marry Horace twenty years ago. However, we might think that she suffered giving in to her brother’s decision, and so conclude that her act of submission in the past could have meant another source for her evil. With the arrival of industrialization, it is now the moment for payback and Regina won’t lose the opportunity to shrewdly fight this battle, even if she needs to play dirty. At the end of the day, Regina doesn’t care about family bonds; she sees Ben and Oscar as merely obstacles for her to make a move. Her insubordination gives her the strength to confront patriarchy but, is she being evil in so doing? As Mary Daly explains in Beyong God the Father, Eve, the first woman, was not evil because of her power but because of her noncompliance. She didn’t show esteem to the powerful, and so she was considered evil.11 Regina’s situation at the beginning of the film is quite similar: she manipulates, deceives, acts coldheartedly, but so far her wrongdoings are morally incorrect actions that do not cause an insufferable harm. Horace, a respected banker, is too kind as compared to the Hubbard men, a bunch of evil foxes who only think about getting material benefits no matter how. As he is a more moral character, Regina despises him more than any other men in her life. She admires Ben’s bright —dirty— skills at making business, but she hates Horace’s kindness. She thinks it is a weakness in a man, and she starts to look down on him. In the nineteenth century it was generally believed that “some women might have lessened fertility simply by limiting sexual encounters. [And] such behavior likely affected the marriage,”12 but Regina clearly rejected Horace because she could not stand him. To a certain extent, money becomes for her a substitute for sex, and her hostility towards Horace becomes partly justified by her ensuing desire to evolve —as a valuable member of the family and as social being— and reach equality, or even superiority to men. As “…the love of money [was] the ultimate determinant of mate selection in twentieth century American marriages”13 and Regina is “entirely and completely focused on making money,”14 she expected a wealthy future from Horace. When he doesn’t “I don’t ask for things I don’t think I can get.” Regina Giddens as portrayal of a New Southern evil in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) ___________________________________________________________________________________ 8 _ provide her with everything she had wanted, she is not only disappointed but also very angry, and even more eager for wealth. Horace is resolved to limit Regina’s power and so he decides that his Union Pacific Bonds must be treated as a loan for his brothers’ in law, not like a share. He thinks he can actually tie Regina, but she is already too powerful and her evil is now becoming more patent: REGINA: Oh, I see. You are punishing me. But I won’t let you punish me. If you won’t do anything, I will. HORACE: You won’t do anything because you can’t. You can make trouble. I shall say and go on saying I let them the bonds. REGINA: You would do that? HORACE: Yes. For once in your life, I’m tying your hands. There’s nothing for you to do. Regina may be cruel but, in my opinion, Horace is spiteful as well. Maybe his intentions are not evil, yet he is the one blackmailing now. For once, Regina is being punished and the audience can perceive the roles of evildoer and victim as inverted. In any case, Regina seems to have been “tied” by Horace’s affability since not long after their marriage, and hence her determination to achieve power and be able to fight what Card would call everyday “unjust inequalities”: It may be argued that some unjust inequalities – inequalities that might not in themselves be evils if they were merely sporadic or isolated incidents in a life that is otherwise, in many respects, flourishing – can become evils if they are very systematic. Being arbitrarily excluded from an activity that one enjoys, and for which one even has an aptitude, might be an example.15 Regina is therefore a victim of evil herself. She has been constantly excluded from the life she has always wanted. She hasn’t been allowed to have power within the family, and she has always been considered a defiant woman for desiring something she shouldn’t wish for. But far from giving up, she gains more power and, given the opportunity, she does not hesitate to become a perpetrator of evil in order to definitely stop being a victim. Ultimately, she lets Horace die and as many other well-know evil women had done in the past, she becomes the embodiment of wickedness. The story of the wife who refuses to save her husband —or rather, who leads him to death— reminds us of Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), Mónica Ledo Fernández 9 ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ by Eugene O’Neill, a famous predecessor of Lillian Hellman, who, in his trilogy takes us back to the Greek mythology. Therefore, the protagonist of the three plays, Christine Mannon, would be a clone of Clytemnestra, the same role Regina Giddens represents. Ezra Mannon could be compared to Agamemnon, the ill husband, thus being the counterpart of Horace Giddens. There is a crime in each case —in the Greek myth, in O’Neill’s play and also in Wyler’s film— given that the merciless wives watch their husbands die and, thus, become murderers. In Greek mythology, Clytemnestra is known as the queen of Peloponesus, married to Agamenon. Furious because her husband had killed their first born, Iphigeneia, she decides to murder him. For Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, evil in the private space, that is, in the family and the household, is epitomized in the character of Clytemnestra as woman, wife and betrayer. Aeschylus compares her domestic evil with public social wickedness and he understands her murder as her ascension to power. For Sophocles, Clytemnestra is not an evil being, but she is a threat for the family and the whole city. In O’Neill’s trilogy, General Ezra Mannon, a Civil War hero, returns from the battlefield and is murdered by his wife Christine. Mannon’s daughter, Lavinia, who loved her father, swears to take revenge on her mother for her father's death. In my opinion, Christine and Regina, like Clytemnestra, are unhappy in their marriages and they are greedy and materialistic, but their husbands are not mere victims, they are probably to blame too. These women are dangerous, but the reason for their evil deeds is their exclusion from the symbolic order within the family —institution in which they feel supported by some members, but alone in the end— and their exclusion from what society thinks of as purely male spheres —that is, from anything related to money. Representative of loneliness and an indomitable rebelliousness against the norm is Antigone,16 another figure of the Greek tragedy, whereas a famous example of a woman who wants to control her husband’s fortune is Shakespeare’s great and avaricious Lady Macbeth.17 As Sadahide Kato points out, Lady Macbeth is not a usual murderess since lust is not what she is drawn by.”18 She is strong-willed and intelligent and, like Regina, she is wicked in her attempt to achieve success and always be herself, without the threat of any rival. Like Regina, Lady Macbeth uses all her persuasive methods in order to get what she wants, but the protagonist of The Little Foxes resorts to blackmail while Macbeth’s wife directly plots the murders she deems necessary. On the other hand, after analyzing the sources for Regina’s evil and come to sympathize with her cause or even pity her to a certain extent, it is 10 “I don’t ask for things I don’t think I can get.” Regina Giddens as portrayal of a New Southern evil in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ not beyond the bounds of possibility that she may be a predecessor for a new kind of 21st century woman. The two most common or visible tendencies of evil women on screen are that of a female predator or a weak “femme fatale.” Predator women appear as sexy vampires or seductive creatures full of power and usually luscious. By way of illustration, we can mention vampire Bill Compton’s stunning wife, the charming and commanding Queen of Vampires, or the bewitching Maenad in one of the most successful television series today, True Blood. Like Regina, they do not fear anything, they set their goals, and they manage to overpower men by means of being morally incorrect or even becoming murderesses. Nowadays, the archetype of femme fatale of the 1940s as we all remember her from film noir has disappeared. This femme fatale seems to have metamorphosized into a new evil woman who, although sexually powerful, does not use her sexuality, but rather her charm and intellect, as a tool against man. Unlike Regina, this woman is not so tied by patriarchal rules, but she has some kind of personal problem through which the audience is supposed to pity (or sympathize with) her as it may be the case of Regina because of her past. As an example we could mention the protagonists of Desperate Housewives or Sex and the City. They are much blander female figures in comparison with Regina, but still selfish and clearly insubordinate to men. To sum up with, they are both powerful and pitiable, similarly to Regina. Ultimately then, we must conclude that “the important determinants of a threatening woman are these three: intelligence, seductiveness, and selfishness.”19 But as every action has an effect, Regina’s bad actions, inevitably, cause many harms. Looking closely at the type of damage that she inflicts will help us to better determine if she should be defined as an evil woman. Two of the effects definitely worth mentioning are absolute family decay and death. Evils, according to Card, are focused on two aspects: One aspect is that they constitute the most serious harms – the most profound, most lasting, least remediable – to one’s well-being or dignity. The other is that the harm results from or is aggravated or supported by wrongdoing (which can take the form of culpable omissions, as in carelessness, recklessness, or callous indifference).20 In the film we can notice both aspects. On the one hand, the harm that Regina causes is a result of several wrongdoings (beguiling, manipulation, blackmail) as well as of culpable omissions (unruliness, negligence, lack of concern). On the other hand, it is an irremediable Mónica Ledo Fernández 11 ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ damage, an injury impossible to cure. Over and about that, she seems to be conscious of every one of her wrongdoings, and so she clearly explains to Horace why she decided to act coldheartedly with him: HORACE: Why did you marry me? REGINA: Because I was lonely when I was young. Yes, lonely. Not in the way people usually mean. I was lonely for all the things I wasn’t gonna get. […] REGINA: No, it wasn’t. It wasn’t what I wanted. But it didn’t take me long to find out my mistake. Then it was just as if I couldn’t stand the sight of you. I couldn’t bear to have you touch me. I thought you were such a soft, weak fool. You were so kind and understanding when I didn’t want you near me. The lies and excuses I used to make to you. And you believed them. That’s when I began to despise you. HORACE: Why didn’t you leave me? REGINA: Where was I to go? What money did I have? Didn’t think about it much. If I had, I’d have known you’d die before I did. But I couldn’t have guessed you’d get heart trouble so early, so bad. I’m lucky, Horace. I’ve always been lucky. I’ll be lucky again. As Horace refuses to follow the Hubbards’ corrupt business methods to amass wealth, Regina starts to despise and reject him —in and out of bed— and make his life difficult. Without money, she had no other option than endurance. But knowing that Horace is so sick now, she’s excited with the idea that he will die soon and she will eventually have the life she has always wanted. Having this kind of thought is cruel, but revealing it to Horace in order to destabilize him is, in my opinion, utterly wicked. With such a malevolent atmosphere created, the climatic moment takes place. Once finished her sincerity speech to Horace, Regina seats on the sofa, with a smile of superiority in her lips, ignoring her husband. Horace finds it difficult to breath and tries to take his medicine, but it suddenly falls down from his trembling hands and is spilled over the floor. He can barely walk and his pain seems to increase. Regina’s expression changes, her smile disappears and there’s a harsh, terrific look in her face. She is very serious and horrified, but she seems to be thinking anyway. She doesn’t doubt for a second. She doesn’t move. Horace understands, and he desperately tries to call for the servant’s help, beginning to walk towards the staircase. Regina remains still without batting an eyelid. She’s like a statue. Only her eyes turn following Horace’s movements until he is out of her sight. She waits until the 12 “I don’t ask for things I don’t think I can get.” Regina Giddens as portrayal of a New Southern evil in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ very last moment, when Horace stops moving —death is imminent—, and then she seems to suddenly come back to life. Agitated and in a rush, she calls for the servants’ help. Later, after talking to her brothers about the stolen bonds and asking for a 75% share, she laughs at Ben’s attempt to get another doctor to save Horace’s life. She’s in high spirits because she knows Horace has few minutes of life and she foresees a life of wealth for her in the future. In conclusion, even though she doesn’t literary poison Horace or kill him with her own hands, there is no doubt she is a murderess and, as such, a portrayal of evil. Another effect of evil, to a certain extent triggered by Horace’s death but not only, is the total destruction of the Giddens family. Horace’s daughter, Alexandra, eventually comes to realize that her mother is not the role model she wants for herself and decides to leave. The feelings and concerns that Card calls “issues of attitudinal response”21 such as guilt, forgiveness or mercy, become now especially relevant, as the focus is the victim or its descendants. Alexandra is in this case the descendant as well as an indirect victim, since she suffers a terrible pain because of her father’s death and the revelation of her mother’s evil. As a consequence, she chooses to abandon the territory of the evildoer (Regina) so as not to live under her legacy. Contrary to Card, Kekes considers evil as something unfair and groundless that “jeopardizes our aspirations to live good lives,”22 and he pays more attention to the tragedy of becoming a perpetrator of evil than to the victim’s suffering. Therefore, evildoers become the victims of their own actions. Regina didn’t mean to cause harm to her daughter, but her recklessness eventually led to this situation, and now she must welcome losses together with profits, her own loneliness together with money’s company. Quoting Janet Brown, “in Burke’s terms, a feminist drama is one on which the agent is a woman, her purpose autonomy, and her scene a society in which women are powerless,”23 but Regina’s tragedy in the film is that she uses evilness in her ascension to power. Her resolution to let Horace die is one of the most intense moments in the film, and is representative of her determination as well as of her malevolence. In the end, Regina does get what she wants, so her evilness has also some positive effects for her: by means of plotting, she easily adapts to modern times, she gains economic and social power, and she breaks up with male domination achieving at least equality. However, she cannot avoid the other side of the coin, that is to say, the negative effects. In conclusion, Regina’s wickedness works as a double-edged sword giving her Mónica Ledo Fernández 13 ___________________________________________________________________________________ _ independence and power as well as bringing her family’s disintegration, personal loss and her own decay. Notes 1 Atrocity 16 Atrocity 6 3 Lebsock 215 4 Atrocity 5 5 Stuart Mill 276 6 Arrighi. Inequality, Introduction 6. 7 Gordon 294-95. 8 Chapter 3 in Censer’s work The Reconstruction of White Southern Womanhood is entitled “What will be my own”. 9 Censer 99. 10 Finney 76. 11 Mary Daly 44-68. 12 Censer 90. 13 (Wakefield 18-19) 14 Wakefield 51 15 Card. Evils and Inequalities. 93. 16 In Sophocles’ tragedy, Antigone —daughter of Oedipus and Iocasta— is punished for burying her brother, something forbidden because he had rebelled against his own city. Antigone says she prefers to follow the divine law than the human one. 17 Macbeth’s wife in Shakespeare’s tragedy Macbeth (1607). She encourages a hesitant Macbeth to kill King Duncan and becomes finally obsessed with the idea that there is blood in her hands. 18 Kato 190. 19 Hallissy 86-7. 20 Evils and Inequalities 96 21 Atrocity 11 22 Kekes 3 23 Janet Brown 15 2 Bibliography