Eversley Bradwell, Sean

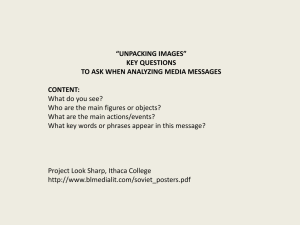

advertisement