Engaging WomEn in Trauma-informEd PEEr

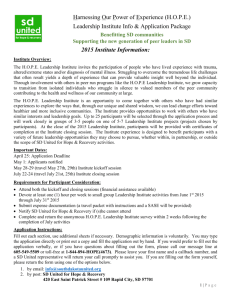

advertisement