coverpages for outlines - The Iowa State Bar Association

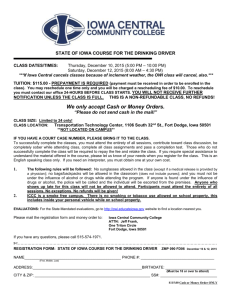

advertisement