Diabetes in the Emergency Department

advertisement

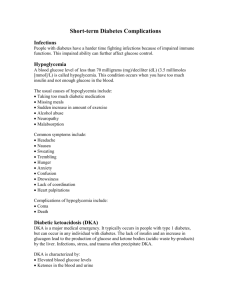

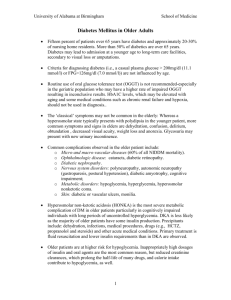

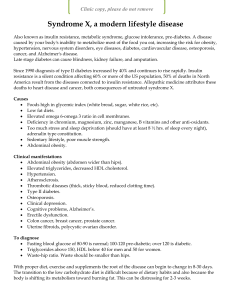

F E A T U R E A R T I C L E Diabetes in the Emergency Department: Acute Care of Diabetes Patients Candace D. McNaughton, MD, Wesley H. Self, MD, and Corey Slovis, MD D iabetes is a common condition, afflicting > 20% of the American population over the age of 60 years.1 Patients with diabetes, particularly those with lower socioeconomic status or limited access to primary care, frequently seek care in hospital emergency departments.2–6 This article will review the most common and immediately life-threatening diabetes-related complications seen in emergency departments: diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), and hypoglycemia. It will also address the evaluation of patients with hyperglycemia and no previous diagnosis of diabetes. Hyperglycemic Crisis: DKA and HHS DKA is responsible for > 110,000 hospitalizations annually in the United States, with mortality ranging from 2 to 10%.7–9 HHS is much less common but confers a much greater mortality.10 In both diseases, mortality is largely related to underlying comorbidities such as sepsis.11 Clinical presentation DKA and HHS are characterized by absolute or relative insulin deficiency, which prevents the body from metabolizing carbohydrates and results in severe hyperglycemia. As blood glucose levels rise, the renal glucose threshold is overwhelmed, and urine becomes more dilute, leading to polyuria, dehydration, and polydipsia. Patients with DKA classically present with the triad of uncon- CLINICAL DIABETES • Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 trolled hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, and increased total body ketone concentration. On the other hand, HHS is defined by altered mental status caused by hyperosmolality, profound dehydration, and severe hyperglycemia without significant ketoacidosis (Table 1).9,12 Initial evaluation Patients with severe hyperglycemia should immediately undergo assessment and stabilization of their airway and hemodynamic status. Naloxone, to reverse potential opiate overdose, should be considered for all patients with altered mentation. Thiamine, for acute treatment of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, should be considered in all patients with signs of malnutrition. In cases requiring intubation, the paralytic succinylcholine should not be used if hyperkalemia is suspected; it may acutely further elevate potassium. Immediate assessment also includes placing patients on a carIN BRIEF This article reviews the most common and immediately lifethreatening diabetes-related conditions seen in hospital emergency departments: diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state, and hypoglycemia. It also addresses the evaluation of patients with hyperglycemia and no previous diagnosis of diabetes. diac monitor and oxygen as well as obtaining vital signs, a fingerstick glucose, intravenous (IV) access, and an electrocardiogram to evaluate for arrhythmias and signs of hyper- and hypokalemia. The differential diagnosis for hyperglycemic crisis includes the “Five I’s”: infection, infarction, infant (pregnancy), indiscretion (including cocaine ingestion), and insulin lack (nonadherence or inappropriate dosing). In addition to clinical history and physical examination, diagnostic tests should include a venous blood gas,13–15 complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and urinalysis; a urine pregnancy test must be sent for all women with childbearing potential. Critically ill patients should undergo additional testing as clinically indicated, including a complete metabolic panel, serum osmolality, phosphate, lactate, and cardiac markers for older patients. A urine drug screen, blood alcohol level, and aspirin and acetaminophen levels should be sent for any patient with unexplained DKA and all patients with HHS. Evaluation for infection or injury should be guided by history and the physical examination. Effective serum osmolality should be calculated (Table 1). The corrected serum sodium is estimated by decreasing measured serum sodium by 1.6 mEq/L for every 100 mg/dl increase in blood glucose over a baseline of 100 mg/dl16,17; for every 100 mg/dl increment increase in 51 F E A T U R E A R T I C L E Table 1. Diagnosis of HHS and DKA Plasma glucose (mg/dl) Venous or arterial pH Serum bicarbonate (mEq/L) Urine or serum ketones* Effective serum osmolality** (mOsm/kg) Anion gap*** Mental status Mild DKA > 250 7.25–7.30 15–18 Positive Variable > 10 Alert Moderate DKA > 250 7.00 to < 7.24 10–15 Positive Variable > 12 Alert/drowsy Severe DKA > 250 < 7.00 < 10 Positive Variable > 12 Stupor/coma HHS > 600 > 7.3 > 18 Small > 320 Variable Stupor/coma By nitroprusside reaction method. Effective serum osmolality: 2[measured Na+(mEq/L)] + [glucose (mg/dl)]/18 + [blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl)/2.8]. *** Anion gap: [Na+(mEq/L) – [(Cl–mEq/L)+ HCO3(mEq/L)]. Adapted from refs. 11 and 13. * ** blood glucose > 400 mg/dl, measured serum sodium is decreased by an additional 4 mEq/L.18 Although DKA and HHS share some similar features, they should be treated as distinct clinical entities with different etiologies and treatments. Patients with DKA require insulin to reverse their ketoacidosis. Patients with HHS require fluid resuscitation first and foremost; they may or may not require insulin, and those who do rarely require a continuous infusion. An algorithm for the initial evaluation and treatment of patients with DKA can be found in Figure 1. Intravenous Fluid Critically ill patients with severe hyperglycemia resulting from DKA or HHS should be treated immediately with a bolus of normal saline.11,19 The average fluid deficit for patients with DKA is 3–5 liters; fluid resuscitation in young, otherwise healthy patients should begin with a rapid bolus of 1 liter of normal saline followed by an infusion of normal saline at 500 ml/hour for several hours.11,19–21 52 Patients with HHS are often severely dehydrated, with cumulative fluid deficits of 10 liters or more. However, because they tend to be older and sicker, they require careful resuscitation. Expert opinion advocates for a rapid bolus of 250 ml of normal saline repeated as needed until the patient is well perfused.19,22,23 Fluid therapy is then continued at a rate of 150–250 ml/ hour based on cardiopulmonary status and serum osmolality.23–25 The choice and rate of IV fluid for patients with DKA who are not critically ill should be based on their corrected serum sodium and overall fluid status. While awaiting laboratory study results, most of these patients may be given a bolus of 500 ml of normal saline.11,19 Patients with mild to moderate DKA should be given normal saline at 250 ml/hour; those with an elevated corrected serum sodium should be given halfnormal saline at 250 ml/hour.26 Insulin therapy Critically ill patients with DKA should be given a loading dose of regular insulin at 0.1 units/kg body weight to a maximum of 10 units followed by an infusion of regular insulin at 0.1 units/kg body weight/ hour, to a maximum of 10 units/ hour.11,19 Other doses and routes of insulin administration have been studied,27–29 but these have not been evaluated outside of the research setting or in critically ill patients.11 Less seriously ill patients with DKA should be given an infusion of regular insulin at 0.1 units/kg body weight/hour without a loading dose to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia. Insulin should not be started until hypovolemia has been addressed and serum potassium has been confirmed to be > 3.5 mEq/L. Giving insulin to patients with a serum potassium level < 3.5 mEq/L may precipitate life-threatening arrhythmias. Expert opinion regarding the use of insulin for patients with HHS is mixed.11,19,22 Because some patients with HHS achieve euglycemia with fluid resuscitation alone,30 and given the theoretical risks of precipitating oliguric renal failure or cerebral edema in inadequately fluid-resuscitated patients,22 insulin should not Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 • CLINICAL DIABETES F E A T U R E A R T I C L E Figure 1. Initial evaluation and treatment of DKA in the emergency department. *Laboratory studies: complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, venous blood gas, urinalysis, urine pregnancy test if female and childbearing age. If critically ill or clinically indicated: complete metabolic panel, serum osmolality, phosphate, lactate, cardiac markers, urine drug screen, blood alcohol level, chest X-ray, or other imaging studies. Calculate effective serum osmolality and corrected serum sodium. Signs of critical illness include 1) altered mental status: 2) signs of hypoperfusion; 3) significant derangement in heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature, or oxygen saturation; or 4) signs of severe acidosis such as marked Kussmaul respirations. BMP, basic metabolic panel; BP, blood pressure; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; hyperK, hyperkalemia; IVF, IV fluids; IVP, IV push; NS, normal saline; O2, oxygen; O2 sat, oxygen saturation; pt, patient; RR, respiratory rate; SC, subcutaneous; temp, temperature; VBG, venous blood glucose. be given as part of initial therapy.31–33 However, if the patient’s serum glucose does not decrease by 50–70 mg/ dl per hour despite appropriate fluid management, a bolus of IV regular insulin at 0.1 units/kg body weight to a maximum of 10 units may be given. Electrolyte replacement Patients with DKA or HHS experience rapid shifts in potassium during CLINICAL DIABETES • Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 resuscitation that may trigger lifethreatening arrhythmias. Death during initial resuscitation of patients with DKA is usually caused by hyperkalemia, whereas hypokalemia is the most common cause of death after treatment has been initiated. Therefore, serum potassium should be checked every 2 hours until it has stabilized in all patients with hyper- glycemic crisis, and these patients should remain on a cardiac monitor. Guidelines for the treatment of hyperkalemia and hypokalemia in patients with hyperglycemic crisis based on expert opinion and our clinical experience are found in Table 2. Many critically ill patients with DKA manifest hypophosphatemia during resuscitation. To avoid potential cardiac and skeletal muscle weakness and respiratory depression from hypophosphatemia, a serum phosphate of < 1.5 mg/dl should be repleted with K2PO4 at 0.5 ml/hour.34 No studies have evaluated replacement of phosphate in HHS, but critically ill patients with HHS should have their phosphate monitored and replaced appropriately. Bicarbonate should not be used routinely in the treatment of DKA or HSS.19 Expert opinion suggests that it may be used in patients with DKA and severe acidosis (pH < 6.9) or in patients with severe hyperglycemia who present with a wide-complex or disorganized cardiac rhythm thought to be caused by hyperkalemia. Several small studies have shown no improvement in mortality when bicarbonate is used in patients with a pH > 6.9.35 Additionally, bicarbonate may prolong hypokalemia,36 has been associated with longer hospitalizations,37 and is thought to cause paradoxical acidosis of the cerebral spinal fluid and decrease oxygen tissue delivery.22 In children, its use has been associated with increased risk of cerebral edema.38 Continued evaluation and treatment All patients with hyperglycemic crisis require fingerstick glucose measurements hourly until they have stabilized. In patients with DKA, an additional bolus of regular insulin at 0.14 units/kg body weight by IV administration should be given if the blood glucose level does not decrease 53 F E A T U R E A R T I C L E Table 2. Replacement Thresholds for Potassium in Hyperglycemic Crisis Serum potassium (mEq/L) Action > 5.3 No additional potassium; recheck in 1 hour 4.0–5.3 Add KCl 10 mEq/L/hour to IV fluids 3.5 to < 4.0 Add KCl 20 mEq/L/hour < 3.5 Hold insulin Add KCl 20–60 mEq/L/hour Continuous cardiac monitoring by 10% in the first hour; the continuous infusion of regular insulin should then resume at the original dose. For patients with DKA, dextrose should be added to the continuous IV fluids once blood glucose has decreased to < 250 mg/dl. Patients with HHS whose blood glucose level decreases to < 300 mg/dl should be observed closely for signs of oliguric renal failure and cardiovascular collapse; these patients may require the addition of dextrose to IV fluids, even without administration of insulin. In the treatment of DKA, expert opinion recommends continuing an insulin infusion until acidosis has resolved and an anion gap is no longer present, but there are no formally endorsed criteria for discontinuing insulin. When converting to subcutaneous insulin, a subcutaneous dose should be given 1 hour before stopping the IV infusion to prevent rebound hyperglycemia.11,19 Each institution should devise a standard protocol to provide consistent care for its patients.39 Patients with DKA or HHS rarely meet criteria to be safely discharged from emergency departments.1 These patients typically require admission to the hospital with hourly blood glucose and neurological checks until they have stabilized. Hypoglycemia Emergencies A definitive diagnosis of hypoglycemia requires Whipple’s triad: 54 symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, low blood glucose, and resolution of symptoms once blood glucose levels normalize.40 In practice, hypoglycemia is generally defined as a blood glucose level < 60 mg/dl.31,41 Severe hypoglycemia, requiring the assistance of another person to regain euglycemia, can cause significant morbidity, particularly in the chronically ill or elderly; it is the cause of death in ~ 3% of insulin-dependent diabetic patients.42 Iatrogenic hypoglycemia is often the limiting factor in glycemic management of diabetes.43–46 In the landmark Diabetes Control and Complications Trial,42 27% of patients with type 1 diabetes on intensive insulin regimens developed severe hypoglycemia annually. Hypoglycemia is one of the most frequent diabetes-related chief complaints seen in emergency departments.47 Because of the high frequency of hypoglycemia as a cause of altered mental status, all patients who present to an emergency department with altered mentation should undergo immediate bedside blood glucose measurement. Oral hypoglycemic agents and insulin as a cause of hypoglycemia Although the differential diagnosis for hypoglycemia includes liver failure, severe sepsis, and renal disease, this article will focus on the most common cause of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes: the use of insulin and oral antidiabetes medications for glycemic control. The type and dose of medication used for glycemic control is crucially important in determining the risk for recurrent hypoglycemia. Biguanides such as metformin decrease hepatic production and intestinal absorption of glucose and decrease the oxidation of fatty acids. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors decrease postprandial absorption of carbohydrates, and thiazolidinediones enhance the effects of insulin without increasing its secretion. These anti-hyperglycemic medications do not cause hypoglycemia when used in isolation. In contrast, sulfonylureas and meglitinides increase insulin secretion and activity and therefore can cause hypoglycemia.48 The half-life for most sulfonylurea medications is 14–16 hours; they can cause severe, prolonged hypoglycemia. Although meglitinides have a shorter half-life, the risk of recurrent hypoglycemia from these medications is unknown; experts urge caution and recommend assuming that these patients have a high risk of recurrent hypoglycemia.49 Treatment of hypoglycemia As with patients who present in hyperglycemic crisis, the initial evaluation of patients with suspected hypoglycemia includes securing the airway and assessing hemodynamic status. Altered mentation and signs of malnutrition should prompt administration of naloxone and thiamine, respectively. Naloxone and dextrose may completely reverse coma and eliminate the need for intubation; whenever possible, they should be given before proceeding to intubation. Once bedside glucose measurement confirms hypoglycemia, treatment should be accomplished immediately with either oral intake Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 • CLINICAL DIABETES F E A T U R E A R T I C L E Figure 2. Treatment of hypoglycemia.BG, blood glucose, IM, intramuscular; SC, subcutaneous. of food, IV dextrose, or intramusDextrose is the treatment of cular glucagon. When decreased choice for hypoglycemia. Glucagon, mentation precludes oral intake 1 mg, may be administered subcuof food, IV dextrose is the firsttaneously or intramuscularly if IV line therapy. One amp of dextrose access is not available, but it requires provides ~ 100 calories, raising 15 minutes or more for onset of blood glucose levels for 30–60 minaction and is associated with utes (Figure 2). The treatment for vomiting. hypoglycemia may have a shorter Blood glucose levels should duration of action than many of the be checked hourly at a minimum. precipitating drugs, and patients Patients who develop recurrent who are successfully treated initially hypoglycemia or whose blood may require repeat doses of glucose. glucose levels decrease despite Additionally, depending on the administration of dextrose should be cause of hypoglycemia (e.g., sulfostarted on continuous IV dextrose. nylurea ingestion), administration These patients require more frequent of dextrose may precipitate rebound hypoglycemia. blood glucose checks—as often as CLINICAL DIABETES • Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 every 15 minutes—and admission to the hospital’s intensive care unit. To prevent and treat undiagnosed Wernicke’s encephalopathy, thiamine at 100 mg IV should be administered to all patients who present with altered mentation and any signs of malnutrition.50 Despite traditional teaching to the contrary, there is no evidence that a dextrose load to reverse hypoglycemia without thiamine replacement acutely precipitates Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Therefore, when treating a patient with altered mental status and confirmed hypoglycemia, or possible hypoglycemia without access to a bedside glucose meter, dextrose should be given immediately; thiamine should be administered as soon thereafter as possible. Treatment with dextrose should not be delayed if thiamine is not immediately available.51 Patients without seizure should return to their baseline mental status immediately once euglycemia is achieved. In the case of a seizure caused by hypoglycemia, phenytoin is should not be considered first-line therapy because it is known to affect insulin secretion and action.52–54 Instead, benzodiazepines, phenobarbital, or levetiracetam may be used.55 Altered mental status that lasts > 15 minutes despite return to euglycemia should prompt reassessment of the patient and broadening of the differential diagnosis to include traumatic or anoxic brain injury, stroke, alcohol intoxication or withdrawal, opioid ingestion, central nervous system infection, liver failure,56 and renal failure. If lumbar puncture is performed, clinicians should be aware that glucose levels in cerebral spinal fluid remain low for several hours after the serum blood glucose level has been corrected.56 55 F E A T U R E Disposition of patients Patients who meet all of the following criteria may be considered for discharge from the emergency department after an episode of hypoglycemia.31 The episode of hypoglycemia was: • Isolated (a single episode of hypoglycemia without recurrence) • Completely and rapidly reversed without the need for a continuous dextrose infusion • The result of an identified cause that is unlikely to cause recurrence • Accidental • Not caused by an oral hypoglycemic medication or long-acting insulin And the patient: • Completed an uneventful 4-hour observation period with serial blood glucose measurements in the normal range and not trending downward • Ate a full meal during the observation period • Has no comorbidities that would interfere with proper administration of medications and intake of food • Understands how to prevent future episodes of hypoglycemia • Can accurately monitor blood glucose at home • Will be with a responsible adult who will monitor the patient • Has close, reliable follow-up with a primary care provider Patients who meet these criteria and are discharged from the emergency department should reduce their insulin dose by 25% for at least the next 24 hours to reduce the risk of recurrent hypoglycemia. Many states require that patients with symptomatic hypoglycemia refrain from driving for 6–12 months and obtain clearance from a physician before resuming driving. 56 A R T I C L E Research has shown that this issue is rarely addressed in the emergency department;57 for public health and the safety of patients, it must be included in discharge instructions. Patients who do not meet all of the above discharge criteria warrant hospital admission. Oral hypoglycemic agents and intermediate- or long-acting forms of insulin (lente, NPH, glargine, and ultralente) are likely to cause recurrent hypoglycemia, and patients taking these medications generally should be admitted. Patients with hypoglycemia that cannot be completely reversed, was caused by massive ingestion or overdose, or is associated with sepsis, starvation, liver failure, or adrenal insufficiency should be admitted to the hospital’s intensive care unit. Suicide attempts, factious disorder, or other psychiatric illnesses should be addressed with a psychiatric consultation. Patients With Undiagnosed Prediabetes or Diabetes Of the 23.6 million Americans with diabetes in 2007, 5.7 million were unaware they had the disease. Additionally, 54 million Americans had prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance).1 Patients who present to the emergency department are at high risk for undiagnosed diabetes;58 in one study, nearly four out of five patients in an urban emergency department met American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria for diabetes screening.59 Currently, the diagnosis of diabetes requires testing performed on two separate occasions unless “unequivocal hyperglycemia” is present.60–62 Patients with unequivocal signs of hyperglycemia such as polyuria, polydipsia, nocturia, or acidosis are likely to need hospital admission, where further testing may be performed. Using an insulin protocol, treatment of hyperglycemia should ideally begin before admission and should not be delayed by confirmatory testing.63 Although hospital emergency departments cannot offer confirmatory testing, patients who are at high risk for prediabetes or diabetes can be identified, and these patients should be counseled regarding their likely diagnosis and lifestyle interventions. A prospective cohort study conducted in an urban emergency department found that all patients with risk factors for diabetes (age > 45 years, polyuria, and polydipsia) and a random blood glucose > 155 mg/dl were later diagnosed with prediabetes or diabetes.63 The use of A1C as a screening tool in emergency departments is being studied59 but is not currently recommended.60 Because most lifestyle interventions are initially unsuccessful,64 certain patients with extremely high risk for undiagnosed diabetes may be considered candidates for initiating the anti-hyperglycemic medication metformin in the emergency department. These patients include those with obesity, family history of diabetes, and polyuria who also have a blood glucose level > 200 mg/dl with no other obvious cause such as trauma or infection. Patients started on metformin in the emergency department should be otherwise healthy, with normal renal function, and should have reliable, close follow-up with a primary care physician. Recommendations from ADA and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes for initiating therapy in patients with newly diagnosed diabetes are as follows:65 1.Begin low-dose metformin (500 mg) once or twice daily with meals (breakfast and/or dinner). Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 • CLINICAL DIABETES F E A T U R E 2.After 5–7 days, if gastrointestinal side effects have not occurred, advance the dose to 850–1,000 mg before breakfast and dinner. 3.If gastrointestinal side effects appear as doses advance, decrease dose to the previous lower dose and try to advance at a later time. 4.The typical therapeutic dose is 850 mg twice daily. Higher doses, up to 2,550 mg daily, can be used but tend to be associated with more significant side effects and are not recommended as starting doses. The most common side effects of metformin are gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Lactic acidosis occurs in 3 per 100,000 patient-years, which is no higher than in the general diabetic patient population.64 Data from a before-after pilot study66 conducted in an urban emergency department suggest that starting metformin in the emergency department may be safe and effective. In this study, emergency physicians treating patients with hyperglycemia but no prior diagnosis of diabetes used an algorithm that provided guidelines for starting and titrating metformin and/or insulin. The majority of the patients with severe hyperglycemia experienced rapid and safe decreases in their blood glucose and A1C levels. Emergency department visits for patients in the intervention group also decreased by 78% from baseline. At a minimum, it is imperative that patients with suspected prediabetes or diabetes be made aware of their abnormal test results and the need for urgent follow-up with a primary care provider. They should be counseled about lifestyle changes. For select patients, starting metformin in the emergency department may be a safe and effective initial medical therapy. However, this CLINICAL DIABETES • Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 A R T I C L E area of diabetes care needs further research and should only be considered as part of a multidisciplinary approach that includes a protocol for initiating diabetes medications that was developed in conjunction with a diabetologist. Summary Hypo- and hyperglycemia caused by diabetes are commonly treated in hospital emergency departments. Physicians must be skilled in diagnosing and stabilizing patients with these conditions. Hypoglycemia related to oral hypoglycemic medications or intermediate- and long-acting insulin requires admission to the hospital. DKA and HHS are best treated with standardized protocols that specifically address electrolyte repletion, insulin dosing, and fluid management. Mortality in both DKA and HHS is often related to underlying comorbidities and the precipitating insult. Patients with prediabetes and diabetes are frequently encountered in emergency departments. A random blood glucose level > 155 mg/dl in the setting of risk factors for diabetes should prompt a referral for a formal evaluation for diabetes. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Department of Veterans Affairs, VA National Quality Scholars Program, with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tenn. (McNaughton and Self). REFERENCES 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National diabetes fact sheet 2007. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/ pubs/factsheets.htm. Accessed 9 February 2011 2 Cutis A, Lee W: Spatial patterns of diabetes related health problems for vulnerable populations in Los Angeles. Int J Health Geogr. Electronically pub- lished ahead of print on 27 August 2010. (DOI:10.1186/1476-072X-9-43) 3 Livingood WC, Razaila L, Reuter E, Filipowicz R, Butterfield RC, LukensBull K, Edwards L, Palacio C, Wood DL: Using multiple sources of data to assess the prevalence of diabetes at the subcounty level, Duval County, Florida, 2007 [article online]. Prev Chronic Dis. Available from http://www. cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/sep/09_0197.htm. Accessed 9 February 2011 4 Bazargan M, Johnson KH, Stein JA: Emergency department utilization among Hispanic and African-American underserved patients with type 2 diabetes. Ethn Dis 13:369–375, 2003 5 Holmwood KI, Williams DR, Roland JM: Use of the accident and emergency department by patients with diabetes. Diabet Med 9:386–388, 1992 6 American Diabetes Association: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 30 (Suppl. 1):S42–S47, 2007 7 Wetterhall SF, Olson DR, DeStefano F, Stevenson JM, Ford ES, German RR, Will JC, Newman JM, Sepe SJ, Vinicor F: Trends in diabetes and diabetic complications, 1980–1987. Diabetes Care 15:960–967, 1992 8 Lebovitz HE: Diabetic ketoacidosis. Lancet 345:767–772, 1995 9 Bagdade JD: Endocrine emergencies. Med Clin North Am 70:1111–1128, 1986 10 Lorber D: Nonketotic hypertonicity in diabetes mellitus. Med Clin North Am 79:39–52, 1995 11 Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN: Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 32:1335–1343, 2009 12 Atchley DW, Loeb RF, Richards DW, Benedict EM, Driscoll ME: On diabetic acidosis: a detailed study of electrolyte balances following the withdrawal and reestablishment of insulin therapy. J Clin Invest 12:297–326, 1933 13 Umpierrez GE, Cuervo R, Karabell A, Latif K, Freire AX, Kitabchi AE: Treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis with subcutaneous insulin aspart. Diabetes Care 27:1873–1878, 2004 14 Brandenburg MA, Dire DJ: Comparison of arterial and venous blood gas values in the initial emergency department evaluation of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Emerg Med 31:459–465, 1998 15 Ma OJ, Rush MD, Godfrey MM, Gaddis G: Arterial blood gas results rarely influence emergency physician management of patients with suspected diabetic ketoacidosis. Acad Emerg Med 10:836–841, 2003 16 Katz MA: Hyperglycemia-induced hyponatremia: calculation of expected serum sodium depression. N Engl J Med 289:843– 844, 1973 57 F E A T U R E 17 Crandall ED: Letter: Serum sodium response to hyperglycemia. N Engl J Med 290:465, 1974 18 Hillier TA, Abbott RD, Barrett EJ: Hyponatremia: evaluating the correction factor for hyperglycemia. Am J Med 106:399–403, 1999 19 Magee MF, Bhatt BA: Management of decompensated diabetes: diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome. Crit Care Clin 17:75–106, 2001 20 Owen OE, Licht JH, Sapir DG: Renal function and effects of partial rehydration during diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes 30:510–518, 1981 21 Waldhäusl W, Kleinberger G, Korn A, Dudczak R, Bratusch-Marrain P, Nowotny P: Severe hyperglycemia: effects of rehydration on endocrine derangements and blood glucose concentration. Diabetes 28:577–584, 1979 22 Filbin MR, Brown DFM, Nadel ES: Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic coma. J Emerg Med 20:285–290, 2001 23 Ennis E, Stahl E, Kreisberg R: The hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome. Diabetes Rev 2:115–126, 1994 24 Luzi L, Barrett EJ, Groop LC, Ferrannini E, DeFronzo RA: Metabolic effects of low-dose insulin therapy on glucose metabolism in diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes 37:1470–1477, 1988 25 Hillman K: Fluid resuscitation in diabetic emergencies: a reappraisal. Intens Care Med 13:4–8, 1987 26 Gamba G, Oseguera J, Castrejón M, Gómez-Pérez FJ: Bicarbonate therapy in severe diabetic ketoacidosis: a double blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial. Rev Invest Clin 43:234–238, 1991 27 Kitabchi AE, Murphy MB, Spencer J, Matteri R, Karas J: Is a priming dose of insulin necessary in a low-dose insulin protocol for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis? Diabetes Care 31:2081–2085, 2008 28 Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Fisher JN, Murphy MB, Stentz FB: Thirty years of personal experience in hyperglycemic crises: diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1541–1552, 2008 29 Fisher JN, Shahshahani MN, Kitabchi AE: Diabetic ketoacidosis: low-dose insulin therapy by various routes. N Engl J Med 297:238–241, 1977 30 West ML, Marsden PA, Singer GG, Halperin ML: Quantitative analysis of glucose loss during acute therapy for hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome. Diabetes Care 9:465–471, 1986 31 Adams J: Adams: Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa., Saunders Elsevier, 2008 32 Matz R: Management of the hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome. Am Fam Phys 60:1468–1476, 1999 33 Carroll P, Matz R: Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus in adults: experience in treating diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar nonketotic coma with low-dose insulin and 58 A R T I C L E a uniform treatment regimen. Diabetes Care 6:579–585, 1983 34 Miller DW, Slovis CM: Hypophosphatemia in the emergency department therapeutics. Am J Emerg Med 18:457–461, 2000 35 Morris LR, Murphy MB, Kitabchi AE: Bicarbonate therapy in severe diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Intern Med 105:836–840, 1986 36 Viallon A, Zeni F, Lafond P, Venet C, Tardy B, Page Y, Bertrand JC: Does bicarbonate therapy improve the management of severe diabetic ketoacidosis? Crit Care Med 27:2690–2693, 1999 37 Green SM, Rothrock SG, Ho JD, Gallant RD, Borger R, Thomas TL, Zimmerman GJ: Failure of adjunctive bicarbonate to improve outcome in severe pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Emerg Med 31:41–48, 1998 38 Glaser N, Barnett P, McCaslin I, Nelson D, Trainor J, Louie J, Kaufman F, Quayle K, Roback M, Malley R, Kuppermann N: Risk factors for cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med 344:264–269, 2001 39 Kanji S, Singh A, Tierney M, Meggison H, McIntyre L, Hebert PC: Standardization of IV insulin therapy improves the efficiency and safety of blood glucose control in critically ill adults. Intens Care Med 30:804–810, 2004 40 Whipple AO, Frantz VK: Adenoma of islet cells with hyperinsulinism: a review. Ann Surg 101:1299–1335, 1935 41 Osorio I, Arafah BM, Mayor C, Troster AI: Plasma glucose alone does not predict neurologic dysfunction in hypoglycemic nondiabetic subjects. Ann Emerg Med 33:291–298, 1999 42 DCCT Research Group: Hypoglycemia in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes 46:271–286, 1997 43 Cryer PE: Hypoglycaemia: the limiting factor in the glycaemic management of the critically ill? Diabetologia 49:1722–1725, 2006 44 Cryer PE: Hypoglycemia is the limiting factor in the management of diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 15:42–46, 1999 45 Cryer PE: Hypoglycemia: still the limiting factor in the glycemic management of diabetes. Endocr Pract 14:750–756, 2008 46 Havlin CE, Cryer PE: Hypoglycemia: the limiting factor in the management of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educ 14:407–411, 1988 47 Brackenridge A, Wallbank H, Lawrenson RA, Russell-Jones D: Emergency management of diabetes and hypoglycaemia. Emerg Med J 23:183–185, 2006 48 Harrigan RA, Nathan MS, Beattie P: Oral agents for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: pharmacology, toxicity, and treatment. Ann Emerg Med 38:68–78l, 2001 49 Rowden A, Fasano C: Emergency management of oral hypoglycemic drug toxicity. Emerg Med Clin North Am 25:347–356, 2007 50 Donnino MW, Vega J, Miller J, Walsh M: Myths and misconceptions of Wernicke’s encephalopathy: what every emergency physician should know. Ann Emerg Med 50:715–721, 2007 51 Hack JB, Hoffman RS: Thiamine before glucose to prevent Wernicke encephalopathy: examining the conventional wisdom. JAMA 279:583–584, 1998 52 Hofeldt FD, Lufkin EG, Hull SF, Davis JW, Dippe S, Levin S, Forsham PH: Alimentary reactive hypoglycemia: effects of DBI and dilantin on insulin secretion. Mil Med 140:841–845, 1975 53 Spellacy WN, Cohn JE, Birk SA: Effects of diuril and dilantin on blood glucose and insulin levels in late pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 45:159–162, 1975 54 Cudworth AG, Barber HE: The effect of hydrocortisone phosphate, methylprednisolone and phenytoin on pancreatic insulin release and hepatic glutathione-insulin transhydrogenase activity in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 31:23–28, 1975 55 Shearer P, Riviello J: Generalized convulsive status epilepticus in adults and children: treatment guidelines and protocols. Emerg Med Clin North Am 29:51–64, 2011 56 Kaplinsky N, Frankl O: The significance of the cerebrospinal fluid examination in the management of chlorpropamideinduced hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 3:248–249, 1980 57 Ginde AA, Savaser DJ, Camargo CA: Limited communication and management of emergency department hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med 4:45–49, 2009 58 Ginde AA, Delaney KE, Lieberman RM, Vanderweil SG, Camargo CA: Estimated risk for undiagnosed diabetes in the emergency department: a multicenter survey. Acad Emerg Med 14:492–495, 2007 59 Ginde AA, Cagliero E, Nathan DM, Camargo CA: Value of risk stratification to increase the predictive validity of HbA1c in screening for undiagnosed diabetes in the U.S. population. J Gen Intern Med 23:1346– 1353, 2008 60 American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2011. Diabetes Care 34 (Suppl. 1):S11–S61, 2011 61 American Diabetes Association: Screening for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27 (Suppl. 1):S11–S14, 2004 62 Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus: Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 26 (Suppl. 1):S5–S20, 2003 63 Charfen MA, Ipp E, Kaji AH, Saleh T, Qazi MF, Lewis RJ: Detection of undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetic states in high-risk emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 16:394–402, 2009 64 Bailey CJ, Turner RC: Metformin. N Engl J Med 334:574–579, 1996 65 Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Heine RJ, Holman RR, Sherwin R, Zinman B: Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initia- Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 • CLINICAL DIABETES F E A T U R E tion and adjustment of therapy. Diabetologia 49:1711–1721, 2006 66 Dubin J, Nassar C, Sharretts J, Youssef G, Curran J, Magee M: STEP-DC: Stop Emergency Department Visits for Hyperglycemia Project—DC [abstract]. Ann Emerg Med 54 (Suppl. 1):S18, 2009 CLINICAL DIABETES • Volume 29, Number 2, 2011 A R T I C L E Candace D. McNaughton, MD, is a clinical instructor in Emergency Medicine; Wesley H. Self, MD, is an assistant professor in Emergency Medicine; and Corey Slovis, MD, is a professor and chairman of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. 59