Part 3 - Interest-Rate-Related Derivatives Growth at Credit

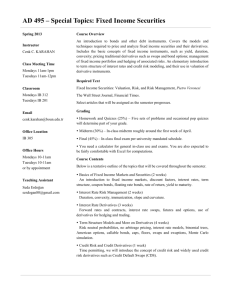

advertisement