CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the study This

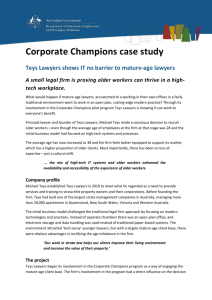

advertisement