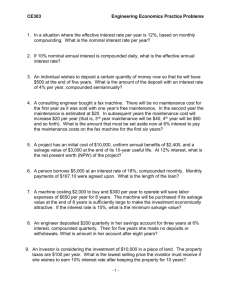

Engineering Economics and Project Management

advertisement