Surviving Modernism:The Live-in Kitchen Including - EMU I-REP

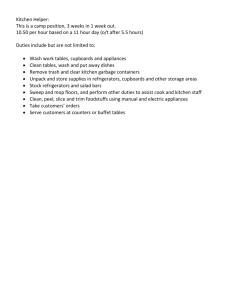

advertisement