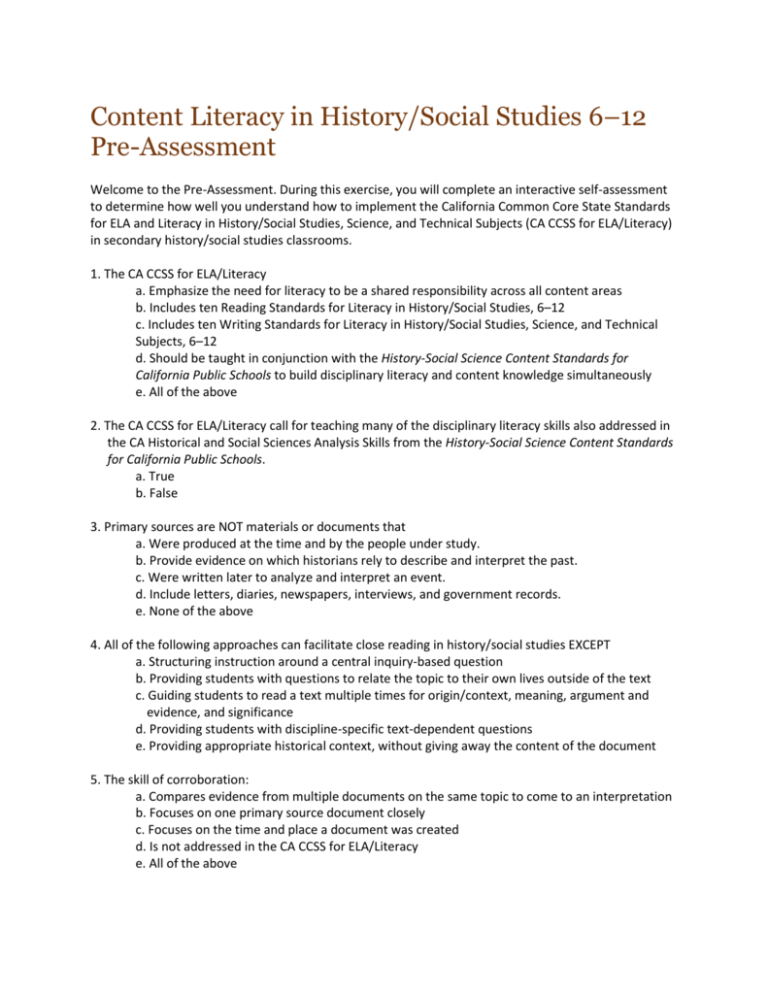

Content Literacy in History/Social Studies 6–12

Pre-Assessment

Welcome to the Pre-Assessment. During this exercise, you will complete an interactive self-assessment

to determine how well you understand how to implement the California Common Core State Standards

for ELA and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects (CA CCSS for ELA/Literacy)

in secondary history/social studies classrooms.

1. The CA CCSS for ELA/Literacy

a. Emphasize the need for literacy to be a shared responsibility across all content areas

b. Includes ten Reading Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies, 6–12

c. Includes ten Writing Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical

Subjects, 6–12

d. Should be taught in conjunction with the History-Social Science Content Standards for

California Public Schools to build disciplinary literacy and content knowledge simultaneously

e. All of the above

2. The CA CCSS for ELA/Literacy call for teaching many of the disciplinary literacy skills also addressed in

the CA Historical and Social Sciences Analysis Skills from the History-Social Science Content Standards

for California Public Schools.

a. True

b. False

3. Primary sources are NOT materials or documents that

a. Were produced at the time and by the people under study.

b. Provide evidence on which historians rely to describe and interpret the past.

c. Were written later to analyze and interpret an event.

d. Include letters, diaries, newspapers, interviews, and government records.

e. None of the above

4. All of the following approaches can facilitate close reading in history/social studies EXCEPT

a. Structuring instruction around a central inquiry-based question

b. Providing students with questions to relate the topic to their own lives outside of the text

c. Guiding students to read a text multiple times for origin/context, meaning, argument and

evidence, and significance

d. Providing students with discipline-specific text-dependent questions

e. Providing appropriate historical context, without giving away the content of the document

5. The skill of corroboration:

a. Compares evidence from multiple documents on the same topic to come to an interpretation

b. Focuses on one primary source document closely

c. Focuses on the time and place a document was created

d. Is not addressed in the CA CCSS for ELA/Literacy

e. All of the above

6. Which of the following discipline-specific history/social studies skills are addressed in the CA CCSS

Reading Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies?

a. Analyzing an author’s point of view or perspective

b. Analyzing an author’s arguments, evidence, claims, and reasoning

c. Analyzing a series of events and determining causation

d. Understanding discipline-specific vocabulary

e. All of the above

7. Although there are no specific speaking and listening standards for literacy in history/social studies

content, these standards can still be addressed effectively in history/social studies instruction and

can contribute to developing effective civic discourse.

a. True

b. False

8. The texts that students should closely read in geography and economics include:

a. Maps

b. Diagrams and other pictures

c. Charts and graphs

d. Financial data

e. All of the above

9. In addition to shared goals, geography and literacy education both focus on which of these outcomes:

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

Strengthening and building vocabulary

Reinforcement of reading and writing strategies

Practical application of comprehension skills

Supplying nonfiction reading and writing topics

All of the above

10. What is one of the great challenges for English learners in a Histroy/Social Studies classes?

a. Watching videos that describe the content being studied

b. Talking with peers in their home language about the topic

c. Comprehending and analyzing primary and secondary sources

d. Working in groups on tasks that require discussion and deeper understanding

e. Close reading of shorter excerpts of complex text

21st Century Skills Map

c reate d in coo peration wi th t h e Nati o nal C o u nci l f o r th e so c i a l stu d i es

This 21st Century Skills Map

is the result of hundreds of

hours of research, development

and feedback from educators

and business leaders across

the nation. The Partnership

has issued this map for the

core subject of Social Studies.

This tool is available at

www.21stcenturyskills.org.

A

21st Century

Skills

B

Skill Definition

The Partnership advocates for the integration of 21st Century Skills into K-12

education so that students can advance their learning in core academic subjects.

The Partnership has forged alliances with key national organizations that represent the core academic subjects, including Social

Studies, English, Math, Science and Geography. As a result of these collaborations, the Partnership has developed this map to

illustrate the intersection between 21st Century Skills and Social Studies. The maps will enable educators, administrators and

policymakers to gain concrete examples of how 21st Century Skills can be integrated into core subjects.

C Interdisciplinary Theme

D Sample Student

Outcome/Examples

An example from the Social Studies 21st Century

Skills Map illustrates sample outcomes for teaching

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

Publication date: 11/08 LEARNING & INNOVAT ION SKILLS

Creativity and Innovation

• Demonstrating originality

and inventiveness in work

• Developing, implementing

and communicating new

ideas to others

• Being open and

responsive to new and

diverse perspectives

• Acting on creative ideas

to make a tangible and

useful contribution to

the domain in which the

innovation occurs

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Students develop

creative solutions to a class or

school problem.

outcome: Students evidence

original thought and inventiveness

in response to an assignment, issue

or problem.

outcome: Students invent an

original piece of work that can be

published or presented online.

EXAMPLE: Students interview

students and/or teachers to identify

a problem (e.g., bullying on the playground) and

as a group brainstorm creative ways to address

the problem (producing a play that examines the

issue, hosting a contest for best ideas).

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

EXAMPLE: Students choose an historical figure

(e.g., Abraham Lincoln, Sojourner Truth) and

create an original story, play, poem or piece of

art that captures/conveys a key aspect of that

person’s life history.

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

EXAMPLE: Working in teams,

students create a simulation, role play, or

webquest that covers a current social or

political issue being covered in the news (e.g.,

global warming, poverty, global economy) or an

historic event (American Revolution, Civil War,

WWII). The finished products can be packaged,

presented and/or donated to a local school, with

an accompanying group analysis and reflection

on the most innovative and creative elements in

each of the products.

Publication date: 11/08 LEARNING & INNOVAT ION SKILLS

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

4th Grade

• Exercising sound

reasoning in

understanding

• Making complex choices

and decisions

• Understanding the

interconnections among

systems

• Identifying and asking

significant questions that

clarify various points of

view and lead to better

solutions

• Framing, analyzing and

synthesizing information

in order to solve problems

and answer questions

outcome: Use technology to

graphically display data about a

community or state public issue

and ask questions about and pose

possible solutions to the issue.

example: Students make a spreadsheet of

the per pupil funding provided to several school

districts within their state and the state math

and reading scores for those districts. They

display the information by district and then by

largest to smallest dollar amount. They discuss

their observations about this data as they seek

to answer such questions as: Which districts

have the highest and lowest funding and scores?

What might the differences be in the schools

in the lowest funded areas compared with the

highest funded areas?

additional notes:

Given the importance of an inquiry approach

to social studies, what follows is a four-step

approach that includes a description of each step

and its alignment with the relevant 21st century

skill. (“Understanding the interconnections

among systems” is an outgrowth of using an

inquiry approach/21st century skills to address

social studies content.)

Step 1: Identify a problem/issue and collect

information so as to define and better

understand the problem/issue. (Exercising sound

reasoning in understanding.)

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Use digitized

resources to investigate and define

political or social issues in the

past and then illustrate, through a

multimedia presentation, how one

such issue relates to their community.

outcome: Using sound reasoning

and relevant examples, students

analyze the historical evolution of

a contemporary public policy issue,

place it within an historical context, and

use a digital publishing tool to report their work.

example: Students use online databases, such

as www.census.gov to determine patterns of

immigration and compare these patterns with

changes in the demographics of their community

and school district.

example: In groups, students explore how

selected societies of the past used their natural

resources for fuel (e.g., England’s use of its forests

at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution)

and the economic impact of that use. Students

use videoconferencing (e.g., www. skype.com) to

collect information from relevant government

officials about the use of corn for biofuel instead

of food and analyze the environmental and

economic implications of this use. Students use

district-approved wikis to publish the results of

their research.

outcome: Working in online

research groups, students research a

contemporary or historic issue, post

significant questions about alternative

courses of action, and/or analyze

the information they have gathered to

generate options for responding to the issue.

example: Students brainstorm a list of

recent and historic natural disasters. Working

in cooperative groups, students research online

the government’s response to a natural disaster,

develop questions, and evaluate the government’s

response. Each group creates a well-reasoned

summary of their findings, posts the results in a

school-approved podcast, and debates alternative

responses in a school-approved blog.

Step 2: Pose questions related to the problem/

issue and recognize how one’s perspective

affects the problem/issue. (Identifying and asking

significant questions that clarify various points of

view and lead to better solutions.)

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

outcome: Use technology to

research and graphically display a

reasonable analysis of and prediction

about a public issue. Working through

a student-safe social networking site, groups

of students post a podcast that presents their

analysis of a current public issue and prediction

about a preferred outcome.

example: Students use voting patterns,

demographic data and socio-economic data

from the U.S. Census bureau for the counties

in their state to predict the outcomes of an

upcoming election. Students display their election

projection, with supporting information, on a

digital map. Based on their predictions, students

Publication date: 11/08 LEARNING & INNOVAT ION SKILLS

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving (continued)

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

Step 3: Analyze a problem and determine

possible solutions to the problem/issue. (Framing,

analyzing and synthesizing information in order

to solve problems and answer questions.)

outcome: Students use a

variety of electronic media

to research and present an

historic event that impacted

the community (e.g., National

History Day).

create a podcast that suggests election strategies

the political parties might utilize for their

candidates.

Step 4: Evaluate solutions to a problem/issue

and then select/justify/act upon a solution to

a problem/issue. (Making complex choices and

decisions.)

outcome: Access information to

discover the interconnections between

government services and their location

in the community.

example: Using electronic reference material,

students investigate how an historic event (e.g.,

Civil Rights Movement or Vietnam War) affected

the local community. Students use clip art, video

and other multimedia products to demonstrate

an interpretation of the event. The students’

presentation should address the key themes of

their analysis.

example: All fourth graders in a school

take an online survey about their sports and

hobby interests, and results are reported in

graphs on the school Web site. Students use GIS

and GPS to find the location of areas in which

these sports can be played throughout their

community and post the results online.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

outcome: Students demonstrate

an understanding through the

use of technology about how the

relationship among social, economic

and governmental systems affects

change in a community over time.

example: Students analyze the relationship

between changes in population in communities

and zoning decisions made by local governments

over a 20-year period by using census data,

digitized zoning maps (Google Earth), population

distribution maps, and transcripts of local

government meetings. Based on this analysis, the

students generate graphic depictions of potential/

predicted growth patterns for a community.

Publication date: 11/08 LEARNING & INNOVAT ION SKILLS

Communication

• Articulate thoughts

and ideas clearly and

effectively through

speaking and writing

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Research, organize and present

historical information in clear, complete and

effective formats.

outcome: Research, organize

and present information in clear,

complete and effective formats.

outcome: Analyze, synthesize, organize and

present information from the social sciences in

clear, complete and effective formats.

EXAMPLE: Working in small groups, students

will choose an area from their state’s history,

organize a storyboard on the person/place/

event, and use digital tools to create a

presentation that teaches their topic to the

remainder of the class.

EXAMPLE: Research information on

the local implications of a global issue of concern

(e.g., child poverty, hunger, homelessness).

Students organize their information and a

possible solution and write a persuasive letter

that is to be proof-read, peer edited, and finally

sent via e-mail to a local public official. EXAMPLE: Research and use concept-mapping

software to create a graphic display (i.e., Venn

diagram) that compares and contrasts various

major world religions in terms of foundations,

beliefs, and relationship to historical and current

issues.

outcome: Interpret, organize and present

information from American history in clear,

complete and effective formats to other students/

adults.

EXAMPLE: Research information on an

issue relevant to an historical period (e.g.,

a determining factor in the outcome of the

American Revolution or the inevitability of the

Civil War) and organize it into a persuasive essay

that is to be proof-read, peer edited, and finally

written and summarized in a class blog and/or

audio podcast.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

outcome: Access and evaluate information

from various sources dealing with elected

officials’ effectiveness while in office.

EXAMPLE: Over an extended period of time,

students efficiently access the voting records of

different state and local officials on issues that

impact their community (i.e., education and

taxes) and create a digital report card of the

selected official(s) using creative presentation

methods such as a podcast, slideshow, Web site

or district-approved blog.

Publication date: 11/08 LEARNING & INNOVAT ION SKILLS

Collaboration

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

• Demonstrating ability

to work effectively with

diverse teams

outcome: As a group, work together to

reach a decision and to explain the reasons

for it.

outcome: As a group, work together to

reach a decision and to explain the reasons for it.

• Exercising flexibility

and willingness to

be helpful in making

necessary compromises

to accomplish a common

goal

example: Working in small groups,

encourage and engage other classmates to

assist with a group service-learning project.

Using digital media, students demonstrate

the need to raise the awareness of their

classmates on an issue within their community,

(e.g., students create a digital poster that

persuades classmates to participate in a school

fundraising project).

outcome: Working in small

groups, students will research a

current issue and analyze it in

terms of historical, political and

economic components, various

viewpoints, and potential solutions,

and create a digital presentation that clearly

describes all sides of the issue.

• Assuming shared

responsibility for

collaborative work

outcome: Work as a team to assess

individual and/or group work.

example: Using a teacher-constructed

online rubric, students work in teams to

review their personal performance and

contributions to their team, as well as overall

group performance.

example: Using an open source asynchronous

discussion forum such as Moodle, students

discuss how to respond to a proposed state law

requiring bicycle helmets and develop consensus

about what the team will do. Using a word

processing program, students work in pairs to

author a persuasive letter either for or against

the proposed law, providing sound reasons to

support their position. Send the letter to the

appropriate legislative official.

outcome: Recognize and communicate

diverse perspectives on an historical issue and

demonstrate how diverse perspectives might

lead to different interpretations of an issue.

(Articulating thoughts and ideas clearly and

effectively through speaking and writing.)

example: After watching videos of an

historical event, students read online first-hand

accounts (e.g., WWII, Korean War, Vietnam War).

Students then use a collaboration listserv such as

Videoconferencing for Learning to find students

in other parts of the country with whom they

can discuss and compare interpretations of the

events. Students then summarize and reflect on

their experiences in small group discussions.

outcome: Seek reasonable and ethical

solutions to problems that arise when scientific

advancement and social norms or values come

into conflict.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

example: Working in small groups, students will

survey favorite forms of recreation among local

teens and research the local history of recreational

youth facilities for teens and the potential sources

of political and economic support. The information

will be graphed and analyzed, and each group

will create a business plan for developing a local

recreation center/club for teens. The survey results,

need and plan will be presented to a community

group or civic association using technology tools.

outcome: Working online with groups of

students from other districts and/or states,

students develop plans to enhance high school

students’ ability to use emerging technologies.

example: Using online surveys, virtual

conferences or videoconferences, students gather

information from peers who participate in virtual

schooling. Students then present the results

and make recommendations about how virtual

schooling might be used in their own setting.

outcome: Work in groups, taking various

roles to plan, investigate and report the results of

their study on a national or global historic and/or

social issue.

Publication date: 11/08 LEARNING & INNOVAT ION SKILLS

Collaboration (continued)

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

example: Working in teams of two to four,

students explore the impacts and effects of an

invention or technological innovation of the

19th century and create a position paper that

analyzes the pros and cons of the invention (e.g.,

impact of the cotton gin on Southern plantations

and slavery).

example: Working in pairs, conduct online

research and create a report on a historic or social

issue (e.g., HIV/AIDS in the U.S. and in an African

nation), and compare the economic, health and

social implications of HIV/AIDS in various settings.

outcome: Communicate to school or

community members about opportunities to

assist with a group project.

EXAMPLE: Working in small groups, students

will choose an area of community service to

research (e.g., United Way, Kids Who Care,

hospital volunteer opportunities, food and

clothing drives, Red Cross). Each group will then

organize, produce and distribute a video or audio

podcast, public service announcement, or a digital

brochure or poster that promotes student and

community collaboration in that effort.

outcome: Assess their performance as a

group and develop and implement a plan to

work together more productively.

example: Students use a district-approved

wiki or asynchronous discussion board to

reflect on a recent group activity, discussing

both strengths and weaknesses of their team’s

interaction and productivity.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

outcome: Reach consensus on a viable action

that could be taken relative to a political and/or

social issue and then act accordingly.

EXAMPLE: Working in student teams and using

online decision-tree tools, research an issue that is

a challenge for the local community and develop

consensus around three specific actions the group

will take to address the issue (e.g., writing letters

to elected representatives or local paper, organizing

an e-mail campaign or other activity). Prepare a

summary report evaluating the group’s decisionmaking process and what action steps were taken.

outcome: Recognize, empathize with, and

communicate diverse perspectives on an issue

and realize how one’s perspective influences one’s

interpretation of an issue and/or work within a

group.

example: In a group, create and implement

an online survey for community members (e.g.,

regarding the effects of the recent influx of

immigrants) and compare responses with digitized

accounts from other communities. Then divide

into two groups and present two opposing

viewpoints on the issue, analyzing the merits of

each perspective.

Publication date: 11/08 INFORMATION, MEDIA & TEC HNOLOGY SK ILL S

Information Literacy

• Accessing information

efficiently and

effectively, evaluating

information critically

and competently, and

using information

accurately and

creatively for the issue

or problem at hand

• Possessing a

fundamental

understanding of the

ethical/legal issues

surrounding the access

and use of information

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Access information

about communities around

the world from a variety of

information sources.

outcome: Create and

organize original information

data sets about key issues in

the community, state or nation

using a variety of tools.

outcome: Access, reference

and present information using

multiple sources that offer diverse

perspectives about economic

issues.

example: Students use digital databases to

gather data regarding gas prices, home heating

oil prices, wages, etc. in their city over the past

12 months and construct a graph illustrating how

these resources have been used.

example: Students will examine information

about federal tax policy from various sources.

Focusing on the federal income tax, excise tax,

and other forms of federal taxation, students

will compare opinions as presented through

several information outlets including popular

digital and print media, online communities (e.g.,

district-approved blogs, online interest groups),

and community resources, and articulate why

some opinions are more compelling or effective

than others.

example: Working in small

groups, students select a nation from each

continent and use online encyclopedias,

electronic databases and other Web sites to

study several examples of daily life in regions

in those nations. They present findings to the

class using presentation software. Students

create a Venn diagram to compare and contrast

two communities from around the world using

illustrations or information to demonstrate

understanding. OUTCOME: Access information from the

expertise of people inside and/or outside their

own community.

example: Students participate in an online

discussion or interactive videoconference with a

museum educator in order to discuss and analyze

an artifact found in the student’s local community,

drawing conclusions about the item’s purpose

and probable owner.

outcome: Access and analyze visual digital

primary information sources and digital maps.

example: Students access and analyze sources

of information about how transportation systems

have been used over time and/or are being

used today using online sources of current and

historical digital images (e.g., digital photograph

libraries, aerial photographs, satellite imagery),

and then draw conclusions about how they are

related to changes in population distribution.

OUTCOME: Gather original data from various

information sources and create graphs or charts

to display the information. (Using information

accurately and creatively.)

outcome: Access and critique sources of

information from various types of media, which

discuss an historic event. Students analyze the

difference between public and private sources of

information.

example: Students use an online survey

tool to create a survey that collects data about

the local attractions their family likes to visit.

Students store the data in a spreadsheet, evaluate

and display their findings using the spreadsheet’s

example: Students access information about

the Civil War from multiple media sources,

including public (e.g., Mathew Brady photo

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

outcome: Develop and use a customized

information gathering strategy to access

multimedia information about a public policy

issue of local, national and/or global significance

and produce an Internet Web page, digital video,

or podcast of the findings.

example: Students create strategies for

locating and using information from digital and

non-digital resources, which includes a selection

of search engines, search parameters, methods

of organizing information once identified,

and a plan for using information for specific

purposes. Students use information they have

gathered from their customized search to

develop a multimedia presentation advocating

for a position on the issue (e.g., improving

migrant laborers’ working conditions, ending

Publication date: 11/08 INFORMATION, MEDIA & TEC HNOLOGY SK ILL S

Information Literacy (continued)

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

graphing tools, and use digital images to

demonstrate their family’s preferences of their

favorite places to visit within in their community

and state.

collection from the Library of Congress) and

private sources (e.g., Ken Burn’s The Civil

War). Students critique these sources given any

possible bias or political perspective as well

as determining what is factual and what is not.

Compare and contrast the sources with regard

to the information that may be used, and the

restrictions or lack of restrictions on access

to the information (e.g., did the private source

require a source for access). Students will then

make appropriate use of the information in

a short report related to the content of the

information.

homelessness in the local community, eradicating

polio or malaria) and produce a podcast for

other students to use in order to better

understand this problem.

OUTCOME: Conduct an interview related to

an important issue in a student’s life or in their

community, evaluate the information, and create a

slide show that describes the main points of the

discussion.

EXAMPLE: Interview a family member about

the changes in how people work or play over

time in their community. Present the main points

that result from the interview in a multimedia

slide show that integrates video images.

OUTCOME: Access and use

relevant information from the

Internet about how the United

States and other nations around the

world address an economic issue.

OUTCOME: Evaluate various sources

of information for use in solving a

problem or addressing an issue.

example: Students consult the U.S. Dept. of

Energy Web site to create a spreadsheet and

construct a line graph of crude oil prices since

the crisis of the early 1970s. They then examine

data on selected oil producing and consuming

countries from the CIA World Facts database and

develop possible explanations for the fluctuations

in price.

EXAMPLE: Students will access

information about an important issue

in their community (e.g., building a new school)

from their local print newspaper, a Web site, and

a person in their family or community and then

evaluate the similarities and differences in the

information.

OUTCOME: Evaluate the nature of information

ownership and the related accessibility of various

forms of information. Examine issues of copyright

and the proper way to cite various sources.

example: Students examine court cases,

such as John Doe v. Alberto Gonzales, and

others related to information access. Students

prepare a summary description of restrictions

to information access imposed on minors and

government access to private information.

Students demonstrate proper citation and ethical

use of sources.

OUTCOME: Understand how to use and

appropriately cite information created by others.

EXAMPLE: Students will access information

about their state (e.g., images from places in the

state, historical narratives, maps) from digital and

non-digital sources. Students will determine who

created the information and appropriately cite

the source.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

Publication date: 11/08 INFORMATION, MEDIA & TEC HNOLOGY SK ILL S

Media Literacy

• Understand how media

messages are constructed,

for what purposes

and using which tools,

characteristics and

conventions

• Examine how individuals

interpret messages

differently, how values

and points of view are

included or excluded, and

how media can influence

beliefs and behaviors

• Possess a fundamental

understanding of the

ethical/legal issues

surrounding the access

and use of information

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Identify specific purposes for

which media messages are constructed.

outcome: Analyze how media format

influences media messages (e.g., “The medium

is the message.” McLuhan). Analyze how the

meaning of a message is influenced by the specific

media and the historic context in which the

message is conveyed.

outcome: Identify and analyze different ways

that electronic news sources define and present an

issue and raise significant questions about how the

different points of view in the news sources might

affect how people define and act upon the issue.

example: Using the Internet and software

that plays audio and/or video clips, students

analyze various advertisements aimed at

children their age and identify the purpose(s)

of each ad.

outcome: Identify different interpretations

of the same message.

example: Using a video news clip from the

Internet about an event associated with a local

or state issue, students identify how many

different interpretations were recorded and

suggest possible reasons for the differences.

outcome: Identify legal uses of information.

example: Using an online scavenger hunt

(such as http://www.geocities.com/stvdlnrds/

etp/scav/), students explain the meaning of

“Copyright” and “Fair Use.”

example: Using history Web sites and primary

sources, students compare and contrast 19th

century and contemporary presidential election

campaigns and hypothesize about the ways in

which media forms of the 19th and 21st century

have similar and different influences on political

campaigns.

outcome: Explain and demonstrate the

importance of copyright law regarding the access

and use of information.

example: Students research and explain the

issues and laws related to the copyright of digital

music. Students demonstrate their understanding

of the ethical issues when they access and use

digital music in presentations.

example: Students access online global news

media sources (e.g., BBC and others) to analyze

how each describes the relations between Israel

and Palestine and the reasons for the conflicts in

that region. They then compare these portrayals

with digitized primary news reports from the

Israeli founding period and articulate how and why

the reasons for the conflict differ.

outcome: Describe how various forms of

visual media (e.g., graphics, color, layout, pamphlet

design, advertisement composition) are designed

to influence beliefs and behaviors. Evaluate specific

visual media with the following criteria: source,

objectivity and technical accuracy.

example: Research a variety of media types and

formats on the same issue (e.g., AIDS prevention).

Create a visual presentation that describes how

information delivered through various forms of

visual media has the potential to influence people’s

behaviors. Evaluate the source, objectivity and

technical accuracy of the visual media.

outcome: Demonstrate a clear understanding

of the many ethical and legal issues related to the

access and use of information.

example: Using the Internet to research U.S.

copyright and plagiarism laws, create a list of

acceptable practices for students and present them

using video, audio and text. Share the presentation

with students at a local middle school or the

public library.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

Publication date: 11/08 10

INFORMATION, MEDIA & TEC HNOLOGY SK ILL S

ICT Literacy

• Using digital technology,

communication tools

and/or networks

appropriately to access,

manage, integrate,

evaluate and create

information in order to

function in a knowledge

economy

• Using technology as

a tool to research,

organize, evaluate and

communicate information

and the possession

of a fundamental

understanding of the

ethical/legal issues

surrounding the access

and use of information

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Use digital technology

and/or networks appropriately to

access information.

outcome: Use digital

technology and/or networks

appropriately to access

information.

outcome: Use digital technology and/or

networks appropriately to access information.

example: Access simulation

software to experience running

a business (e.g., a lemonade stand). Discuss

factors that influence business decisions

(e.g., supplies, resources, location, potential

customers, price, capital equipment).

example: Conduct research using

the Internet and electronic library databases to

identify and describe the roles of international

and multinational humanitarian organizations.

Formulate a list of questions about each agency’s

role in helping children. E-mail the questions

to the proper contact person at one of the

identified organizations.

outcome: Use digital technology

appropriately to manage and integrate

information from various sources.

example: After accessing digital and print

archives, use a presentation tool to depict a

timeline of an historical event in community or

state history. Incorporate images, text, sound,

animation and/or graphics to enhance the

timeline.

outcome: Use digital technology

appropriately to evaluate information in order

to function in a knowledge economy.

example: Use technology tools to examine

the interaction of human beings and their

physical environment: the use of land, building

of cities, and ecosystem changes in selected

locales and regions. Compare a dated aerial

photo of one’s own community and a more

recent aerial photo captured online. Identify the

changes that have taken place and evaluate the

changes that have occurred.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

outcome: Use digital technology

appropriately to manage and integrate

information from various sources.

example: Create a database of information

about international and humanitarian

organizations and include the data provided by

the agencies about their work with children.

example: Use search engines, online

databases, or identify and join a list serve to

access national and international media to

examine an international conflict. Focus on

the interactions of ethnic, national or cultural

influences on the conflict.

outcome: Use digital technology

appropriately to manage and integrate

information from various sources.

example: Create an online document with

hyperlinks to help middle school students

understand an international conflict. Use the

hyperlinks to provide background information

and context for past and current events in the

conflict.

outcome: Use digital technology to evaluate

information.

outcome: Use digital technology to evaluate

information.

example: Evaluate the extent to which

existing aid for children provided by humanitarian

organizations is sufficient to meet the needs

globally and locally.

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

example: Embed evaluation questions in the

online document to encourage students’ critical

thinking about an international conflict as they

encounter hyperlinks within the document.

Publication date: 11/08 11

INFORMATION, MEDIA & TEC HNOLOGY SK ILL S

ICT Literacy (continued)

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Using digital technology,

communication tools and/or networks

appropriately to create information and share

with the school or local community.

outcome: Using digital technology,

communication tools and/or networks

appropriately to create information.

outcome: Using digital technology,

communication tools and/or networks

appropriately to create and share information.

example: Write a letter to the editor, sharing

data about the existing aid for children from

humanitarian organizations and the unmet needs

in the local community. Suggest ways that young

people can become involved.

example: Create an online document that

summarizes what students have learned about

an international conflict and post to a district or

school Web site for other students. example: Participate in a monitored wiki,

for youngsters by youngsters, or post to a class

Web site and share the presentation on local

or state landforms and geographic features.

example: Invite a business member of the

local Chamber of Commerce to the class to

listen to the students’ presentations about

their business simulation and comment on

their conclusions, or use videoconferencing for

students’ presentations and discussions with

the business representative.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

Publication date: 11/08 12

LIFE & C AREE R SKILLS

Flexibility and Adaptability

• Adapting to varied roles

and responsibilities

• Working effectively in a

climate of ambiguity and

changing priorities

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Students recognize that citizens

must “give and take” so that a democratic

system both guarantees rights and assigns

responsibilities fairly.

outcome: Students understand how

compromise is embedded in the legislative

process of the House of Representatives (e.g.,

writing and proposing bills, committee hearings

and amendments, bringing a bill to the floor for

full House vote).

outcome: Students analyze the needs and

wants of co-existing community constituencies

and enact a situation in which they must work

together.

example: Members of the class contact or

visit a local court to find out how citizens are

called to jury duty. By creating a calendar or

weekly wheel, students use their own blind

selection process to divide tasks in their own

classroom. Hold a class meeting to discuss how

to handle responsibilities when a student is

absent.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

example: Students research two different

bills in Congress dealing with immigration issues,

learning how to navigate the government’s

complex online presence by using www.house.

gov. They then construct a sample compromise

bill that includes compatible parts of each of the

bills. Respond to presidential veto.

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

example: In a jigsaw activity, students

study the Web sites of local agencies (e.g., fire

department or city planning department) and

organizations (e.g., Chamber of Commerce)

and role play the concerns and roles of each in

a situation such as population growth, revenue

needs, a community event (parade, fair, sporting

event) or a crisis (flood, fire, evacuation). Include

a scenario in which agencies must suddenly

change plans to deal with the situation beyond

their control.

Publication date: 11/08 13

LIFE & C AREE R SKILLS

Initiative and Self Direction

• Monitoring one’s own

understanding and

learning needs

• Going beyond basic

mastery of skills and/or

curriculum to explore

and expand one’s own

learning and opportunities

to gain expertise

• Utilizing time efficiently

and managing workload

4th Grade

8th Grade

outcome: Students participate in writers’

workshop and, with the teacher’s help,

evaluate their writing skills and set goals for

improvement.

outcome: Students choose a research

topic and seek additional resources to become

“experts” on their topic. Students set short- and

long-term goals to complete their research on

time.

example: Students write a draft article

for the class newsletter about a field trip or

community event they attended, share their

letter with peers in a writers’ workshop, and

with the teacher’s help, set a goal to improve

their writing, (e.g., creating a clear topic

sentence for each paragraph).

• Defining, prioritizing and

completing tasks without

direct oversight

12th Grade

example: Students choose an historic figure

to research, plan their online and offline research

strategy to seek additional resources beyond

those available in the classroom and become

“experts” on their topic in preparation for a

History Fair or History Hall of Fame. Each time

students work on the project, they evaluate and

record their progress and set the next steps on a

project management log.

• Demonstrating initiative

to advance skill levels

towards a professional

level

• Demonstrating

commitment to learning

as a lifelong process

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

Publication date: 11/08 14

LIFE & C AREE R SKILLS

Social and Cross-Cultural Skills

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

• Working appropriately

and productively with

others

outcome: Students value their fellow

classmates and work with them to complete

inquiries about problems of common interest.

outcome: Students simulate political

organizations based on compromise and

cooperation.

outcome: Students organize around a topic

of local interest and engage in community-based

work directed at some positive action.

• Leveraging the collective

intelligence of groups

when appropriate

example: Students work in small groups to

discuss problems that they have observed or

heard about in their school such as bullying or

graffiti. Convening as a whole class, students

should come to some common agreement

about the problems that are most meaningful.

After the problem has been selected by

consensus, students take responsibility for

specific elements of an inquiry into the causes

of and possible solutions to the problem.

example: As part of a simulation of

Congressional debate over extension of slavery

into the “western” territories in the 1850’s,

students form political parties that are engaged in

debate. Students in each political party would be

required to work together to craft their message

and deliver it to another group of students by

producing a two to three minute presentation in

support of their position.

example: Students identify a public policy

issue in their community, preferably related

to school policy, and work as a whole class

or in small groups. Students create a wiki for

mobilizing others who are interested in the issue.

This would require agreement on the primary

positions taken by the group and coordination

among students for the purpose of articulating a

persuasive message. outcome: Students produce representations

of an historical figure using multiple presentation

genres.

outcome: Students create an

economic venture that requires

the application of economic

principles such as supply and

demand.

• Bridging cultural

differences and using

differing perspectives to

increase innovation and

the quality of work

outcome: Students produce a class skit

or play depicting some episode in their state’s

history.

example: Students work together as a

whole class to identify an historical episode

in their state’s history. Then, in smaller groups,

students construct a skit or play that includes

a script, costumes, a set, and some direction

and production. The groups would also perform

the skit or play. All or some parts of the skit

or play could also be recorded and possibly

produced, given the ability of the teacher to

support such work, for viewing by audiences

outside the classroom.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

example: Students work in pairs or groups,

determined by their interest and abilities, in

various presentational genres including audio,

video, still imagery, creative text, narrative,

expository writing, music, etc. Each pair or group

researches an historical figure from their state

(possibly a common person as opposed to a

political, military, business figure) and creates

a representation, using the genre selected, of

this person’s life story or some event(s) from

their life. A montage of these projects could

be presented for a wider school or community

audience.

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

example: Students work together as a class or

in groups to execute a simple business task such

as selling a certain amount of a popular snack by

a certain date. The activity could be structured

competitively or in such a way that various

groups are attempting to reach group-based

specific sales goals. Students use a range of sales

techniques that incorporate forms of technology

such as video and web-based promotion. Students

could also create a new product or packaging of

an existing product and make a competitive pitch

to fellow students who decide which product

or packaging should be awarded with a “venture

capital” type of investment. The activity could be

incorporated into a co-curricular school-based

venture that has access to some start-up funds.

Publication date: 11/08 15

LIFE & C AREE R SKILLS

Social and Cross-Cultural Skills (continued)

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Students work with

partners in other school settings

to explore daily life in different

cultural contexts.

outcome: Students explore characteristics of

dialect within their community or state, including

vocabulary, word use, grammar and cultural

distinctions that reflect historical trends and

events.

outcome: Students organize a cultural

exhibit for their community.

example: Students use an

educationally oriented global network such as

the non-profit iEARN (International Education

and Resource Network) or the United

Nations’ UNICEF, Voices of Youth project.

Students engage children or children’s stories

in vastly different cultural contexts and develop

an understanding of the similarities between

the life experiences in these two places. This

should be clearly focused on similarities in the

children’s lives and may or may not involve

actual communication with children from

another country. Children represent their

knowledge in some format, such as oral reports

or poster presentations.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

example: Students and/or teachers identify

specific dialect groups in their community or

state and study that group in the context of its

history and cultural traditions. Students record

the stories of people in these communities who

speak with recognizable forms of the dialect and

construct reports on the historical and cultural

significance of the groups.

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

example: Students identify cultural groups in

their community and engage these groups for

the purpose of showcasing the groups’ creativity

or productivity. Students plan and host a cultural

fair that showcases the actions and activities

of real people in real parts of the community.

The cultural fair is held after school hours and

includes people from the community who are

first generation immigrants or who represent

strong cultural traditions sharing some aspect of

their work in the community.

Publication date: 11/08 16

LIFE & C AREE R SKILLS

Productivity and Accountability

• Setting and meeting

high standards and

goals for delivering

quality work on time

• Demonstrating diligence

and a positive work

ethic (e.g., being

punctual and reliable)

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Through a service-learning

project that requires the sharing of work

activities, students develop awareness of our

responsibility to help others in society who

experience a crisis.

outcome: Students develop

entrepreneurial skills by

undertaking a business project.

outcome: Students complete a project which

incorporates problem identification, research,

a written and oral presentation, and a related

service project. Students evaluate their own work

with project criteria, set goals for improvement,

and strive to meet project deadlines.

example: The class chooses a fundraising

project with direct significance to its current

social studies curriculum (e.g., hurricane relief,

UNICEF aid to Africa, United Way, Red Cross).

Students read about the situation and about

groups that are trying to help, and then split

up responsibilities for sales, donations, record

keeping and other tasks. Students set individual

and team goals and assess their progress and

modify as needed.

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

example: JA World Wide (Junior

Achievement) provides a semester project for

middle school students, in which business leaders

from the community teach a weekly class, and

each student group in the class develops and

markets a product.

Students are responsible for setting goals,

developing and implementing their plans,

monitoring their progress in developing and

marketing their product, and modifying as needed.

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

example: Students participate in National

History Day, Mock Trial competition, or other

social studies related long-term, multi-step

projects. Publication date: 11/08 17

LIFE & C AREE R SKILLS

Leadership and Responsibility

• Using interpersonal and

problem-solving skills

to influence and guide

others toward a goal

• Leveraging strengths of

others to accomplish a

common goal

• Demonstrating integrity

and ethical behavior

• Acting responsibly with

the interests of the larger

community in mind

4th Grade

8th Grade

12th Grade

outcome: Develop problem-solving and

leadership skills while seeking to leverage and

guide the skills of others toward a common

goal. Demonstrate responsibility and ethical

behavior.

outcome: Develop problem-solving and

leadership skills while seeking to leverage and

guide the skills of others toward a common goal.

Use electronic tools to gain community support.

Demonstrate responsibility and ethical behavior.

outcome: Develop problem-solving and

leadership skills while seeking to leverage and

guide the skills of others toward a common goal.

Use electronic tools to gain community support.

Demonstrate responsibility and ethical behavior.

example: Students develop interpersonal

and problem solving skills as they participate in

a school-wide service project (e.g., beautify the

school grounds or help plant a neighborhood

garden). Students in each fourth grade class

discuss what each class can contribute to the

group effort. Student leaders from each fourth

grade class meet together with their teachers

to plan the responsibilities of each class. Class

leaders post on the class Web site or wiki

the responsibilities of each class. Parents are

encouraged to log onto the class or school

Web site to find out how they and their

students can support the project.

example: After investigating children’s needs

in the local community, students participate in

a service project to collect clothing, books and

toys for children at a local homeless shelter.

They solicit community support through posting

on the school Web site, creating public service

announcements for local media, and collaborating

with other groups in the school or community

social service organizations. Class members

provide input regarding their strengths and

interests, which the group leader uses to assign

tasks for the service project.

Students develop a list of qualities of helpful

leaders and followers. During the project,

class leaders and group members assess their

own actions according to these qualities.

(Note: class leaders should rotate during the

year so every student has the opportunity to

experience leadership responsibilities.)

The group leader posts the responsibilities

of each member on the class Web site with a

timeline for completion.

example: Students investigate online social

actions sites (e.g., Free the Children, iEARN,

Mercy Corps, or Taking It Global,) and select the

group most attuned to what the students want

to achieve. Students choose one of the issues

(e.g., support women’s micro-business project

in Africa). Then students research and analyze

the potential contributions of other student

groups, local organizations and/or policy leaders

and devise a strategy to secure and leverage

their support. Via a district-approved social

networking site, students engage in an ongoing

online discussion with representatives from each

of the participating groups (public or private,

local, national or international). Throughout the

project, students evaluate their progress toward

accomplishing their goal as they demonstrate

responsibility and ethical behavior.

After using offline and online means to interact

with community officials about the local homeless

shelter, students prepare recommendations in the

form of an electronic presentation for relevant

community leaders to gain additional funding or

resources for the shelter. outcome: Students select individuals that

best represent ethical leaders in the local, state,

national or international community and illustrate

ways that they can emulate them by acting upon a

social concern.

example: Students develop an "ethical leader

hall of fame” Web site and post examples of

how they might act in a similar manner on a

social concern of their choice. For example,

students might choose Nobel Peace Prize winner

Yunus and provide examples of student action

in support of the Micro-Banking Project in

Bangladesh. The Web site could include a blog

so that other students could rank their favorite

leaders in real time and post their comments. 177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

Publication date: 11/08 18

Supporting Structures

The followin g i tems a re su ggested as to o ls th at ca n be i nteg r ated i nto t h e p rece d i n g exampl es :

8th Grade

12th Grade

• Access to the Web and personal computing

• Brainstorming, concept mapping software

• CAI and simulation software

•Digital images

•Digital production tools (digital photography and video)

• GIS and GPS tools

• Graphics software (drawing, painting, image editing)

•Interactive online sites

• Multimedia resources (clip art, video, sound, animations)

•Ongoing professional development on the promotion of an inquiry approach through the use of technology

•Online authoring, brainstorming, graphics, spreadsheet and presentation software

•Online collaboration, conferencing, communication tools

•Online sources

• Presentation tools

• Print resources including books, newspapers, magazines and maps

• Productivity/publishing tools (ex. word processing, page layout, etc.)

•Resources in the local community including people, places and information

• Search engines and online search strategies

• Social networking sites

• Software applications for creating information content including Web authoring, podcasting, video and other audio tools

• Spreadsheet and graphing software

• TV, Video and DVD

• Videoconferencing and interactive TV

• Video editing software

•Web publishing software

•Word processing software

177 N Church Avenue, Suite 305

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-623-2466

21stcenturyskills.org

Publication date: 08/07 19

Common Core Shifts for English Language Arts/Literacy 1. Building knowledge

through content-­‐

rich nonfiction

Building knowledge through content rich non-­‐fiction plays an essential role in literacy and in the Standards. In K-­‐5, fulfilling the standards requires a 50-­‐50 balance between informational and literary reading. Informational reading primarily includes content rich non-­‐fiction in history/social studies, science and the arts; the K-­‐5 Standards strongly recommend that students build coherent general knowledge both within each year and across years. In 6-­‐12, ELA classes place much greater attention to a specific category of informational text—literary nonfiction—than has been traditional. In grades 6-­‐12, the Standards for literacy in history/social studies, science and technical subjects ensure that students can independently build knowledge in these disciplines through reading and writing. To be clear, the Standards do require substantial attention to literature throughout K-­‐12, as half of the required work in K-­‐5 and the core of the work of 6-­‐12 ELA teachers. 2. Reading, writing and

speaking grounded in

evidence from text,

both literary and

informational

The Standards place a premium on students writing to sources, i.e., using evidence from texts to present careful analyses, well-­‐defended claims, and clear information. Rather than asking students questions they can answer solely from their prior knowledge or experience, the Standards expect students to answer questions that depend on their having read the text or texts with care. The Standards also require the cultivation of narrative writing throughout the grades, and in later grades a command of sequence and detail will be essential for effective argumentative and informational writing. Likewise, the reading standards focus on students’ ability to read carefully and grasp information, arguments, ideas and details based on text evidence. Students should be able to answer a range of text-­‐dependent questions, questions in which the answers require inferences based on careful attention to the text. 3. Regular practice with

complex text and its

academic language

Rather than focusing solely on the skills of reading and writing, the Standards highlight the growing complexity of the texts students must read to be ready for the demands of college and careers. The Standards build a staircase of text complexity so that all students are ready for the demands of college-­‐ and career-­‐level reading no later than the end of high school. Closely related to text complexity—and inextricably connected to reading comprehension—is a focus on academic vocabulary: words that appear in a variety of content areas (such as ignite and commit). More on the shifts at achievethecore.org General Page 2

General Page 3

Comparing the CA CCSS Reading Standards for Literacy in History/Social Studies 6–12

with the CCR Anchor Standards for Reading

CA CCSS Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6–12 (RH) (pp.77-78)

Grade 6–8 Students

Grade 9–10 Students

Grade 11–12 Students

1. Cite specific textual evidence to

support analysis of primary and

secondary sources.

2. Determine the central ideas or

conclusions of a primary or

secondary source; provide an

accurate summary of the text distinct

from prior knowledge or opinions.

3. Identify key steps in a text’s

description of a process related to

history/social studies (e.g., how a bill

becomes a law, how interest rates

are raised or lowered).

4. Determine the meaning of words

and phrases as they are used in a

text, including vocabulary specific to

domains related to history/social

studies.

5. Describe how a text presents

information (e.g., sequentially,

comparatively, causally).

6. Identify aspects of a text that

Key Ideas and Details

1. Cite specific textual evidence to

support analysis of primary and

secondary sources, connecting

insights gained from specific details

to an understanding of the text as a

whole.

2. Determine the central ideas or

2. Determine the central ideas or

information of a primary or

information of a primary or

secondary source; provide an

secondary source; provide an

accurate summary of how key events accurate summary that makes clear

or ideas developed over the course

the relationships among key details

of the text.

and ideas.

3. Analyze in detail a series of events 3. Evaluate various explanations for

described in a text; determine

actions or events and determine

whether earlier events caused later

which explanation best accords with

ones or simply preceded them.

textual evidence, acknowledging

where the text leaves matters

uncertain.

Craft and Structure

4. Determine the meaning of words

4. Determine the meaning of words

and phrases as they are used in a

and phrases as they are used in a

text, including vocabulary describing

text, including analyzing how an

political, social, or economic aspects

author uses and refines the meaning

of history/social studies.

of a key term over the course of a

text (e.g., how Madison defines

faction in Federalist No. 10).

5. Analyze how a text uses structure

5. Analyze in detail how a complex

to emphasize key points or to

primary source is structured,

advance an explanation or analysis.

including how key sentences,

paragraphs, and larger portions of

the text contribute to the whole.

1. Cite specific textual evidence to

support analysis of primary and

secondary sources, attending to such

features as the date and origin of the

information.

6. Compare the point of view of two

6. Evaluate author’s differing points

CCR Anchor Standards for

Reading (p. 74)

1. Read closely to determine what

the text says explicitly and to make

logical inferences from it; cite specific

textual evidence when writing or

speaking to support conclusions

drawn from the text.

2. Determine central ideas or themes

of a text and analyze their

development; summarize the key

supporting details and ideas.

3. Analyze how and why individuals,

events, and ideas develop and

interact over the course of a text.

4. Interpret words and phrases as

they are used in a text, including

determining technical, connotative,

and figurative meanings, and analyze

how specific word choices shape

meaning or tone.

5. Analyze the structure of texts,

including how specific sentences,

paragraphs, and larger portions of

the text (e.g., a section, chapter,

scene, or stanza) relate to each other

and the whole.

6. Assess how point of view or

reveal an author’s point of view or

purpose (e.g., loaded language,

inclusion or avoidance of particular

facts).

7. Integrate visual information (e.g., in

charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or

maps) with other information in print

and digital texts.

8. Distinguish among facts, opinion,

and reasoned judgment in a text.

9. Analyze the relationship between a

primary and secondary source on the

same topic.

10. By the end of grade 8, read and

comprehend history/social studies

texts in the grades 6–8 text

complexity band independently and

proficiently.

or more authors for how they treat

of view on the same historical event

the same or similar topics, including

or issue by assessing the authors’

which details they include and

claims, reasoning, and evidence.

emphasize in their respective

accounts.

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

7. Integrate quantitative or technical 7. Integrate and evaluate multiple

analysis (e.g., charts, research data)

sources of information presented in

with qualitative analysis in print or

diverse formats and media (e.g.,

digital text.

visually, quantitatively, as well as in

words) in order to address a question

or solve a problem.

8. Assess the extent to which the

8. Evaluate an author’s premise,

reasoning and evidence in a text

claims, and evidence by

support the author’s claims.

corroborating or challenging

conclusions with other information.

9. Compare and contrast treatments

of the same topic in several primary

and secondary sources.

9. Integrate information from diverse

sources, both primary and secondary,

into a coherent understanding of an

idea or event, noting discrepancies

among sources.

Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity

10. By the end of grade 10, read and

10. By the end of grade 12, read and

comprehend history/social studies

comprehend history/social studies

texts in the grades 9–10 text

texts in the grades 11–12 text

complexity band independently and

complexity band independently and

proficiently.

proficiently.

purpose shapes the content and style

of a text.

7. Integrate and evaluate content

presented in diverse media and

formats, including visually and

quantitatively, as well as in words.

8. Delineate and evaluate the

argument and specific claims in a

text, including the validity of the

reasoning as well as the relevance

and sufficiency of the evidence.

9. Analyze how two or more texts

address similar themes or topics in

order to build knowledge or to

compare the approaches the authors

take.

10. Read and comprehend complex

literary and informational texts

independently and proficiently.

21

Grades Six

Through

Eight

Historical and Social Sciences Analysis Skills

The intellectual skills noted below are to be learned through, and applied to, the content

standards for grades six through eight. They are to be assessed only in conjunction with

the content standards in grades six through eight.

In addition to the standards for grades six through eight, students demonstrate the following

intellectual reasoning, reflection, and research skills:

Chronological and Spatial Thinking

1. Students explain how major events are related to one another in time.

2. Students construct various time lines of key events, people, and periods of the historical

era they are studying.

3. Students use a variety of maps and documents to identify physical and cultural features

of neighborhoods, cities, states, and countries and to explain the historical migration of

people, expansion and disintegration of empires, and the growth of economic systems.

Research, Evidence, and Point of View

1. Students frame questions that can be answered by historical study and research.

2. Students distinguish fact from opinion in historical narratives and stories.

3. Students distinguish relevant from irrelevant information, essential from incidental

information, and verifiable from unverifiable information in historical narratives and

stories.

4. Students assess the credibility of primary and secondary sources and draw sound con­

clusions from them.

5. Students detect the different historical points of view on historical events and determine

the context in which the historical statements were made (the questions asked, sources

used, author’s perspectives).

21

California Department of Education

Reposted June 23, 2009

22

GRADES SIX THROUGH EIGHT

Historical Interpretation

1. Students explain the central issues and problems from the past, placing people and

events in a matrix of time and place.

2. Students understand and distinguish cause, effect, sequence, and correlation in historical

events, including the long- and short-term causal relations.

3. Students explain the sources of historical continuity and how the combination of ideas

and events explains the emergence of new patterns.

4. Students recognize the role of chance, oversight, and error in history.

5. Students recognize that interpretations of history are subject to change as new informa­

tion is uncovered.

6. Students interpret basic indicators of economic performance and conduct cost-benefit

analyses of economic and political issues.

California Department of Education

Reposted June 23, 2009

40

Grades Nine

Through

Twelve

Historical and Social Sciences Analysis Skills

The intellectual skills noted below are to be learned through, and applied to, the content

standards for grades nine through twelve. They are to be assessed only in conjunction

with the content standards in grades nine through twelve.

In addition to the standards for grades nine through twelve, students demonstrate the following