auditing small entities

advertisement

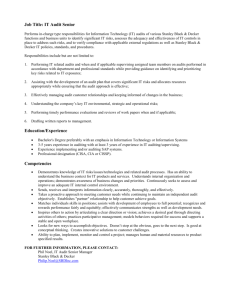

Auditing small entities: Extract AUDITING SMALL ENTITIES EXTRACT © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 1 Auditing small entities: Extract CONTENTS Course overview 1 Learning objectives 1 Course content 1 Small entities audit manual 1 Assumed knowledge 2 Knowledge assessment 2 Symbols2 1. Audit overview 4 The objective of the auditor 4 Australian Auditing Standards (ASAs) 4 Audits of smaller entities 5 2. Audit methodology 7 The benefits of a risk based audit methodology 7 Over-arching principles Independence and ethical principles Threats to independence Professional judgement Professional scepticism Audit documentation Quality control Overview of the methodology 8 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 3. Phases of the audit: Acceptance and continuance 16 Agreeing the terms of an audit engagement (ASA 210) Preconditions for an audit Small entities audit manual resources 17 17 18 4. Phases of the audit: Planning 19 Why plan an audit? 19 Understanding the business 20 Understanding internal control The control environment The risk assessment process Information systems Control activities Monitoring 21 21 22 22 22 22 Obtaining the information 23 Effective risk assessment Inherent risk Significant risks Control risk Detection risk Audit risk Fraud risk assessment Audit assertions and risks Link between risks and controls 24 25 26 26 27 27 28 29 31 2 © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 Auditing small entities: Extract Controls32 Testing the design of a control 32 Testing the operating effectiveness of a control 32 Focus on a common control – bank reconciliation 35 Materiality 35 Responses to the risks 37 The audit plan 38 The audit program 38 The planning phase 40 Small entity audit manual resources 40 5. Phases of the audit: Performance and review 41 Substantive testing Substantive analytical procedures Tests of detail Sample within a sample/selection Type of procedures The reliability of audit evidence External confirmations GS019 Auditing Fundraising Revenue of Not-for-Profit entities Changes to the audit approach What audit work needs to be reviewed and by whom? 42 42 44 46 46 47 48 48 49 49 6. Phases of the audit: Evaluation, report and wrap-up 51 Evaluation 51 Audit differences 51 Analytical review procedures 52 The completion memorandum 52 The management representation letter 53 Communicating with those charged with governance Communicating internal control deficiencies 53 54 Engagement quality control review 54 Subsequent events testing 55 The audit report 55 Assembly of the final audit file Small entities audit manual resources 56 56 Case study questions 57 Case study: Planning 57 Case study: Golf club 58 Case study: Audit client background 59 Glossary 78 Suggested answers 81 Self-assessment81 Case studies Case study: Planning Case study: Golf club Case study: Audit client background © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 83 83 84 87 3 Auditing small entities: Extract 1. AUDIT OVERVIEW An audit is an independent examination of the financial statements to enhance the degree of confidence of intended users in the financial statements. This is achieved by the expression of an opinion by the auditor on whether the financial report is prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with an applicable financial reporting framework. In an audit, an auditor obtains reasonable assurance in arriving at an audit conclusion. To be in a position to express an audit conclusion in the positive form required in a reasonable assurance engagement, it is necessary for the auditor to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence as part of a systematic engagement process involving the following: • Obtaining an understanding of the subject matter and other engagement circumstances which, depending on the subject matter, includes obtaining an understanding of internal control. • Based on that understanding, assessing the risks that the subject matter information may be materially misstated. • Responding to assessed risks, including developing overall responses, and determining the nature, timing and extent of further procedures. • Performing further procedures clearly linked to the identified risks, using a combination of inspection, observation, confirmation, re-calculation, re-performance, analytical procedures and enquiry. Such further procedures involve substantive procedures including, where applicable, obtaining corroborating information from sources independent of the responsible party, and depending on the nature of the subject matter, tests of the operating effectiveness of controls. • Evaluating the sufficiency and appropriateness of evidence. The auditor obtains sufficient, appropriate audit evidence to ensure the risk of a material misstatement is reduced to an acceptably low level. Reasonable assurance is not absolute assurance (i.e. a statement confirming 100% accuracy) due to: • the use of selective testing; • the inherent limitations of internal control; • the fact that much of the evidence available to the practitioner is persuasive rather than conclusive; • the use of judgement in gathering and evaluating and forming conclusions based on that evidence; and • in some cases, the characteristics of the subject matter when evaluated or measured against the identified criteria. THE OBJECTIVE OF THE AUDITOR ASA 200 contains the objectives of the auditor: • To obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements as a whole are free from material misstatement, due to fraud or error, thereby enabling the auditor to express an opinion on whether the financial statements are prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with an applicable financial reporting framework; and • To report on the financial statements and communicate as required by the ASAs, in accordance with the auditor’s findings. AUSTRALIAN AUDITING STANDARDS (ASAS) The Australian Auditing Standards are based on the International Auditing Standards issued by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). The use of international standards ensures consistent quality audits across a number of jurisdictions. 4 © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 Auditing small entities: Extract The professional bodies in Australia require compliance with the Australian Auditing Standards for all audits and any audits performed under the Corporations Act 2001 require compliance with Auditing Standards through the sections of the Act. Similar requirements exist for audits performed under other legislation also (e.g. Associations Incorporation Reform Act 2012 (Victoria) applicable for Victorian Incorporated Associations). • Australian Auditing Standards are applicable to all audits performed in Australia: – Corporations Act audits and other statutory audits where the law requires the application of Auditing Standards – Auditing Standards have the force of law. TIP – All other audits – Auditing Standards are enforceable by the Professional Bodies. • Auditing Standards are scalable (i.e. able to be used on all size of audits) since: – Smaller audits would have less complexity and therefore a number of Auditing Standards may not be relevant (for example, Service Entities, Using the Work of an Expert) but where a requirement is applicable then it must be complied with. – The Auditing Standards acknowledge that the volume of audit documentation is likely to be lower for smaller entities and certain documents may be able to be combined (for example, the audit plan and audit strategy). Nevertheless auditors of these smaller organisations have to consider the relevance of each requirement in the Auditing Standards. The over-riding theme throughout the Australian Auditing Standards is that an ‘Audit is an Audit’ and therefore all requirements in the standards need to be complied with. Auditing Standards The Auditing Standards apply to audits of all sizes and complexities since it is in the public interest that users of audited financial statements have confidence that the audits have been performed at a high standard. The format and contents of each of the Auditing Standards is the same and is set out as below: • Introduction – scope and effective date. •Objective. •Definitions. •Requirements. • Application and other explanatory material. The Auditing Standards contain a requirements section which includes all the mandatory requirements (the traditional ‘black letter’ paragraphs) which is supported by the guidance section (the traditional ‘grey letter’ paragraphs). Auditors however are required to consider all paragraphs within each standard. Auditing Standards can be accessed on the AUASB website at: <www.auasb.gov.au>. AUDITS OF SMALLER ENTITIES • Planning and performance of an audit depends on the size and complexity of the client. • Generally smaller entities have: TIP – Simpler transactions. – Less complex group structures. – Simpler internal controls. © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 5 Auditing small entities: Extract All audits are not planned and performed in the same way. Specific audit procedures to comply with the ASA’s may vary considerably depending on the size and complexity of the entity. The work effort for the audit of a small and medium entity (SME) may differ from that in a large audit because they involve much simpler transactions with the result that audits will generally be more straightforward. For example, the requirement to understand the entity and its environment will be much easier to carry out for an SME. Similarly internal controls in an SME are usually simpler with the result that while the auditor is still required to obtain an understanding of internal control, the auditor can usually obtain and document that understanding more quickly. However there are still a significant number of requirements to be complied with even for a smaller, simpler engagement. ‘Considerations Specific to Smaller Entities’ are included within some of the Auditing Standards, some examples are: • standard audit programs or checklists drawn up on the assumption of a few relevant control activities may be used for the audit plan of an SME audit provided that they are tailored to the circumstances of the engagement; • audit evidence for elements of the control environment in SMEs may not be available in documentary form. Consequently, the attitudes, awareness and actions of management or the owner-manager are of particular importance to the auditor’s understanding of an SMEs control environment. While the auditor of an SME must comply with all relevant ASAs, not all ASAs may be relevant to an SME. Even when an ASA is relevant to an SME, not all requirements of every ASA will be relevant when performing an audit of an SME (e.g. holding an engagement team discussion as part of risk assessment activities is not necessary if it is a one-person audit team). 6 © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 Auditing small entities: Extract 2. AUDIT METHODOLOGY Focus on risks • Identify the risks specific to the entity. • Respond to them. The fundamental methodology in the Auditing Standards, being risk based, is applicable for all audit engagements performed in Australia – regardless of: • the type of entity; • whether there is a fee charged; or • who is the auditor. THE BENEFITS OF A RISK BASED AUDIT METHODOLOGY • Time flexibility – performed earlier in the year. • Increased focus on key areas – better understanding of the risks. • Elimination of tests of details in low risk areas. • Identification of internal controls. • Ability to identify weaknesses in internal control. • The audit effort is directed to addressing the high risk areas. • Unnecessary audit procedures are scoped out. • Audit staff know what is expected of them. Some of the traps with a risk based approach are: • The risk assessment process is performed in ‘addition’ to other substantive work resulting in inefficiency and increased audit costs. WARNING • Too much focus on completing checklists rather than using professional judgement to scale the work. • Standard audit programs are used on all engagements. • Low risk areas might be over-audited. • Planning work is done in isolation. The diagram below shows the overall steps which we need to go through on each audit to ensure compliance with the Auditing Standards. We will cover each phase of the audit in more detail throughout this course. © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 7 Auditing small entities: Extract Figure 1: The steps of the audit PROFESSIONAL JUDGMENT AND SCEPTICISM Risk identification and assessment Business understanding Review, report and wrap-up Response to risks (substantive testing) QUALITY CONTROL DOCUMENTATION Acceptance/ continuation Systems and key controls assessment INDEPENDENCE/ETHICAL PRINCIPLES OVER-ARCHING PRINCIPLES Prior to discussing the detailed phases of an audit, we will cover the over-arching principles which need to be in place for each audit: • Independence and ethical principles; • Professional judgment and scepticism; • Documentation; and • Quality control. Independence and ethical principles ASA 102 Compliance with ethical requirements when performing audits, reviews and other assurance engagements provides that the auditor shall comply with relevant ethical requirements, including those pertaining to independence, when performing audits, reviews and other assurance engagements. ASA 102 defines relevant ethical requirements as including the applicable requirements of: • APES 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, in particular section 290; •The Corporations Act 2001 (relevant for audits performed in accordance with the Corporations Act only); and • Other applicable law or regulation (if appropriate). APES 110 states that ethical principles governing the auditor’s professional responsibilities include: •integrity; •objectivity; • professional competence and due care; •confidentiality; • professional behaviour. The concepts of objectivity and independence are fundamental to auditing, since the auditor’s objective is to enhance, through the expression of an independent opinion, the credibility of the reported financial information of an entity. 8 © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 Auditing small entities: Extract The conceptual framework approach in APES 110 requires auditors to identify, evaluate and respond to any identified threats that may compromise compliance with the fundamental principles. If the identified threats are anything other than clearly insignificant, auditors are required to apply safeguards to eliminate such threats or reduce them to an acceptably low level so that compliance with the fundamental principles is no longer compromised. If appropriate safeguards cannot be implemented then the engagement should be declined or discontinued. Threats to independence It has been noted that auditors don’t always think through threats and therefore think about safeguards which may need to be put in place on audit engagements. The threats listed below are the most common ones which need to be considered for each audit: Self-interest – may occur as a result of the financial or other interests of a professional accountant. Self-review – may occur when a previous judgement needs to be re-evaluated by the person or firm responsible for that judgement. Advocacy – may occur when a professional accountant promotes a position or opinion to the point that subsequent objectivity is compromised. Familiarity – may occur when, because of a long or close relationship with a client, a professional accountant becomes too sympathetic to their interests or too accepting of their work. Intimidation – may occur when a professional accountant may be deterred from acting objectively because of actual or perceived threats. ASA 220 Quality Control for an Audit of a Financial Report and Other Historical Financial Information requires the engagement partner on an audit to form a conclusion on compliance with the independence requirements applying to the audit engagement which are contained in the Code of Ethics. This compliance should be considered as part of the acceptance and continuance phase early in the audit cycle and the conclusion should be documented. For smaller firms, complying with these independence requirements can create particular challenges because of their size and often their business model that they are a ‘one-stop shop’ for their clients. Consider the following processes which at a minimum should be put in place for the audit practice: • having an annual independence confirmation process for assurance personnel to confirm compliance with policies and procedures; • having processes in place for the approval of non-audit services to audit clients; and • having partner succession planning when the firm only has a small number of partners, making partner rotation more difficult (whilst this is currently only required for listed clients and certain other entities, there may be times when a partner needs to be rotated off an engagement). Additional resources available on independence are: • The ‘Independence guide’ (4th edition, February 2013) issued by the Joint Accounting Bodies. • APES 110 Code of Ethics published by the Accounting Professional and Ethical Standards Board: <www.apesb.org.au>. © CPA Australia Ltd 2014 9