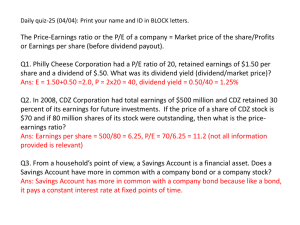

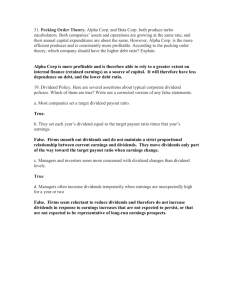

Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies

advertisement