Contribution to structural timber book

advertisement

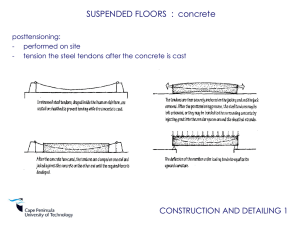

66 Innovation and Continuity Work I find it interesting how, within a specific cultural context, the tectonic expression of a new material finds form; how, as new technologies develop, there are bursts of creative invention. In recent architectural history an interesting example of this was the development of the steel frame in Chicago between 1880 and the end of the century. The early use of steel from the 1850’s onwards either demonstrated the new materials engineering prowess or treated it as a substitute for another material and handled it in a comparative manner. What distinguished the work of the architects of the Chicago School was the manner in which material innovation of the 19th century steel skeleton was utilised as a means with which to revitalise the architectural tradition within which it was used. Innovation and Continuity Spans and heights were achieved that were simply not possible with masonry and timber construction, yet the resultant architecture by Louis Sullivan and others was notable for it’s sophistication rather than its novelty or macho bravado. Clearly in the tradition of the Italian Palazzo, these buildings were of previously unimaginable sizes. Yet they combined this with a sensitivity to detail and composition that reinforced the human scale and a refinement of architectural language that reasserted their place within a cultural continuum. 68 Innovation and Continuity There was a similar period in the early twentieth century following the development of reinforced concrete. Though concrete was an ancient material, its use was transformed when, in 1892, the French engineer and contractor Francois Hennebique patented his reinforced concrete construction system. In the following decades architects and engineers questioned, both through theories and constructed buildings and structures, what this new material could do and how it might be used. In this period, the role of the French architect Auguste Perret, who combined his architectural practice with the contracting firm he ran with his brothers, A & G Perret, was of particular interest. His interest lay simultaneously in what distinguished concrete as a material, and in what ways it related to other materials and their construction systems, most notably stone and the traditional timber frame. The series of buildings he constructed over a thirty-year period from the turn of the century onwards represented a continual process of questioning and refinement to this end. From the 25 bis rue Franklin apartments in Paris of 1903, where the concrete frame and infill were distinguished externally through the use of non-decorative and decorative ceramic tiling, through his first use of an exposed concrete frame in the Marboef Garage of 1905, to the mature works of the 1920’s and 30’s which were constructed entirely in concrete, with the structure clearly legible, Perret’s aim was to establish the new material within a continually developing classical-rationalist tradition. In these buildings a belief in revealing and expressing the new material goes hand in hand with an identification with the tradition of trabeated construction throughout architectural history. Work It seems to me that at the beginning of the 21st century in Europe we are at an analogous moment in the development of engineered timber. Whilst crosslam has been in use now for over a decade, the understanding of what distinguishes this material as new and how it relates to established tectonic theory feels to still be at a tentative phase. Its material attributes are perhaps closest to those of precast concrete, being a panelised material that is produced off-site to high tolerances, yet at times its appearance can resemble in-situ cast concrete. In common with steel it has a complex relationship between material expression and fire-proofing. Its tactile quality is perhaps closest to traditional wood cladding whilst its thermal properties are perhaps without precedent and its acoustic performance is entirely distinctive. To me these questions as to what is truly innovative about the material, what qualities are shared and how it can be used are part of the excitement in constructing with cross-laminated timber; simultaneously considering how the material can fulfil its tectonic potential and how its innovative character sits within the culture of architectural development. In the house I designed for my own family, crosslam was used as the primary material, forming both the frame and the internal walls. It is combined with concrete that provides a plinth-like base and traditional hardwood joinery that comprises the elements one regularly touches. There is a reciprocal relationship with each and at times the solid timber seems closer to one and at times the other. When light falls obliquely across the timber surface, the impression, reinforced by structural legibility, is of timber shuttered concrete, but when one sits on the floor and leans against it, the warmth and subtle give is unmistakably that of timber. Hugh Strange Principal at Hugh Strange Architects, designers of Strange House and Shatwell Studios