Phil 122- Anderson Outline of Nozick`s Entitlement Theory

advertisement

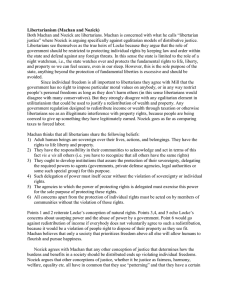

Phil 122- Anderson Fall 06 Outline of Nozick’s Entitlement Theory - Nozick defends an extreme version of market society wherein property rights are virtually absolute. He has the burden of showing this would be a just form of social organization. He cannot simply rely on the commonly held claim that free markets with private property ownership are maximally efficient (Why not?) nor that market societies minimize the risk of tyranny (Why not?). - Nozick’s main argument for absolute property rights follows from his thesis of selfownership as the basic moral value. Self-ownership is one way of describing the value of autonomous self-direction: the freedom to live our own lives in accordance with our own conception of a good life provided we do not violate the basic rights to life, liberty and property of others. Note that Nozick is a moral egalitarian at the level of basic human rights, but definitely not egalitarian about the outcome of this system of values. - How does Nozick get from the basic value of self-ownership to the conclusion that property rights are absolute? He goes part-way with Locke: As a self-owner, I own my talents and abilities in the sense that I alone have a right to determine how I use them. But I cannot claim ownership of my talents and the exercise of them if others have a legitimate claim on the fruits of those talents. That would make others a part-owner of me, thus violating the basic value of self-ownership. - But there is a hitch: the fruits of one’s labor are rarely the product of one’s labor alone. We usually must make use of (a) things purchased from others in the market and (b) of things either unowned (for example?) or (b) owned in common, that is, publicly owned (for example?). Nozick pays no attention to (b), important as it is in contemporary life, since in his entitlement theory there is no room for public ownership. Should he allow for some kinds of public ownership? What troubles would it make for his theory? - Let us focus on (a). I can legitimately make use of things purchased in the market through voluntary transfer. Right? Wrong; I can legitimately use what I have obtained through voluntary transfer only if the person from whom they were obtained was himself a legitimate owner of them. This chain of legitimacy must be traceable all the way back to a point of initial acquisition, which must also be legitimate in some way or other. What makes an initial acquisition of property legitimate? - There is a tendency of some readers to dismiss Nozick at this point on the grounds that (a) Historically, perhaps a majority of initial acquisitions and subsequent transfers came about by force and therefore violated someone’s rights, but (b) it is impossible for us to learn which current holdings have such a history. Therefore, we should abandon the entitlement theory. But that conclusion moves too quickly. Nozick himself admits that, given this sorry history of human rapacity, there should be a one-time egalitarian redistribution of property, after which the entitlement theory could be put into practice. (Is this a realistic possibility?) More importantly – from a philosophical standpoint – Nozick still must explain how an initial acquisition could be legitimate, for if it cannot be legitimate, neither can the principle of transfer be legitimate and the whole theory collapses. Remember that Nozick’s theory is an historical theory of justice. - Nozick argues, again borrowing from Locke, that an initial acquisition is legitimate provided it leaves others as well-off as they were prior to the acquisition (the “Lockean proviso”). A simple illustration: suppose Amy and Ben are both making use of the same unowned land to grow crops, graze their animals, obtain wood, etc. Amy decides (while Ben is away perhaps) to appropriate the land for herself, leaving Ben with the option of either working for her for a wage or moving elsewhere. Suppose that moving is not a rational option for Ben. Thanks to Amy’s managerial skills and the division of labor, the productivity of the land improves such that both parties are now better off, even though Amy as owner takes the larger share of the gains for herself. This appears to satisfy the Lockean proviso as Nozick interprets it. - But is Ben really better off? Amy’s appropriation seems to deprive Ben of two imporant freedoms: (a) He did not give his consent to the takeover and was not asked for it. (b) He has no say over how his labor will be expended; he must accept Amy’s terms of employment. It is difficult to reconcile these losses of liberty with the libertarians’ strong commitment to self-ownership and autonomy. But it gets worse. Suppose Ben is an even more talented manager than Amy, such that if he had made the initial appropriation of the land, hiring Amy for a wage, he and Amy both would be still better off. Or suppose they could have decided to jointly own the land in common and by intelligent planning come out even better still. There are many other possible ownership schemes that could be imagined (Such as?). None of these seem to matter on Nozick’s account. Amy was the first to appropriate and she didn’t violate the Lockean proviso, so the property is legitimately hers. This puts a great deal of weight on the purely arbitrary factor of who decided to appropriate first. It doesn’t seem to matter that there are other imaginable schemes of appropriation that would be both more efficient and more respectful of autonomy. The mere fact that people are better off, under this system of ownership, relative to life in an unowned commons, seems to be an insufficient test of justice.